Unmet Desire

Many local policymakers want to develop more informal collaborations with researchers, but to bridge the gap scientists and institutions will need to understand and accommodate their priorities.

I vividly remember March 2020, the month the United States shut down as COVID-19 spread uncontrollably and upended daily life. At the time, I worked at Cornell University in upstate New York. As we adjusted to a new normal, my Cornell colleague Elizabeth Day and I suspected that local leaders were facing unprecedented policy challenges that were not making the major headlines.

We decided to reach out to county policymakers throughout upstate New York, inviting them to share challenges they were facing. We offered to discuss research that might prove helpful. Responses soon poured in.

One county executive was trying to figure out how to provide childcare for first responders. Childcare centers were ordered closed, but first responders could not stay home to watch their kids. The executive needed systematic research on other options. A second local policymaker watched as her county’s offices shuttered and work moved online; she needed research on how other local leaders had used mobile vans to provide necessary services to rural residents without internet. Another county official sought to design a high-quality survey to elicit frank responses from municipal leaders about COVID-related challenges. In this case, she needed to discuss the fundamentals of survey design and implementation with an expert.

These responses led us to engage in an informal collaboration with each of these policymakers. By informal collaboration, I mean a collaborative exchange in which people with diverse forms of knowledge, expertise, and lived experience share what they know with the goal of developing an expanded understanding of a problem—yet still remain autonomous decisionmakers. In these cases, we as researchers brought knowledge about policy analysis and survey fundamentals, and the policymakers brought detailed knowledge about their present needs, local context, and historical challenges. All this diverse information was crucial to chart a way forward that was informed by evidence.

Yet it turns out our interactions were highly unusual. During our conversations, all the policymakers revealed that researchers from colleges and universities in their immediate area had never reached out in this way, and that they had no regular communication with local researchers.

We as researchers brought knowledge about policy analysis and survey fundamentals, and the policymakers brought detailed knowledge about their present needs, local context, and historical challenges.

This disconnect is a problem. Local policymakers are responsible for almost $2 trillion of spending annually, and they oversee many areas in which technical knowledge is essential, such as promoting economic development, building and maintaining roads, educating children, policing, fighting fires, determining acceptable land use, and providing public transportation. And because of the design of the US system, local officials are also responsible for protecting public health. As Michele Barry, senior associate dean for global health at Stanford University, remarked in March 2020: “We have a completely decentralized public health system.… We don’t even work from the states up. We work from the counties up.”

Curious about whether our experience was representative, in 2021 I conducted a national survey of local policymakers as part of a separate project. I found that our anecdotal experience was in fact representative of a broader scarcity of informal collaborations between local policymakers and researchers—and of local policymakers’ unmet desire for more such interactions. As a result, I see an important yet currently missed opportunity for researchers to become more involved in policy. But doing so will require both institutional support and introspection from researchers themselves. First, institutions and funders must assist and incentivize researchers to initiate and maintain these valuable informal collaborations with local policymakers. Second, researchers must learn more about these policymakers and their needs, and how their expertise can meet those needs.

Policymakers’ unmet desire for science

In the popular press, policymakers are frequently portrayed as either pro-science or anti-science, which is taken to reflect, in part, how much they value the work of university-based researchers. However, it turns out that many policymakers—across the political spectrum—have an unmet desire for science. My research found that they would like, but often do not have, collaborative exchanges with researchers to discuss scientific evidence relevant to policy challenges they are facing. To be sure, scientific research alone rarely determines the shape of public policy, and that’s especially the case if findings run counter to policymakers’ political leanings. That said, we do have many examples in which collaborative exchange between policymakers and researchers has been essential for informing the design and evaluation of new policies. For instance, it was integral in developing successful public health policies related to secondhand smoke, seatbelt use, and the spread of disease.

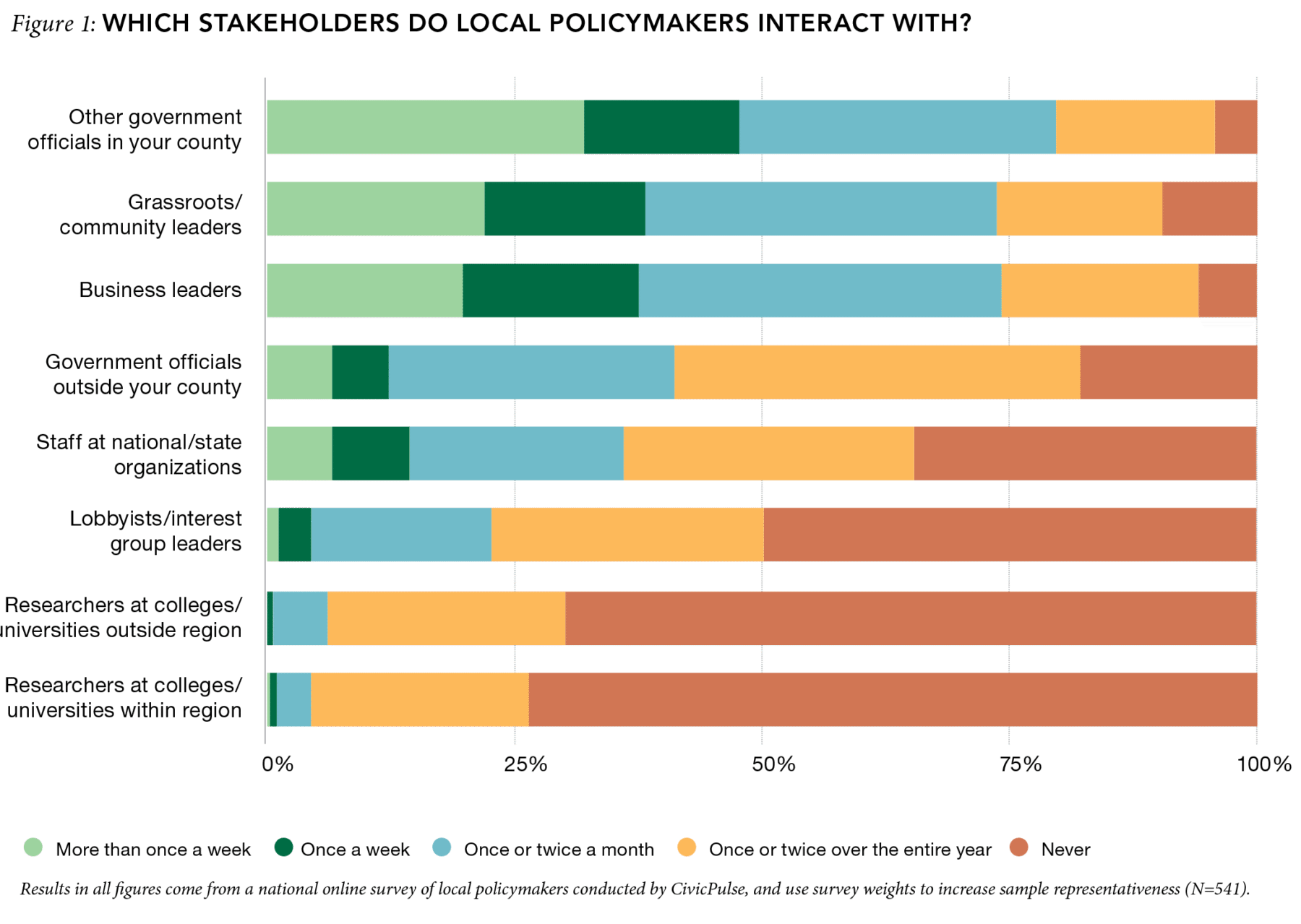

In spring 2021, I designed a national survey of local policymakers (including county and municipal officials) to learn if they have an unmet desire for science. CivicPulse, a nonprofit research organization that maintains a large contact list of local policymakers, fielded the study and provided survey weights to increase sample representativeness. As Figure 1 shows, local policymakers interact far more with other stakeholder groups than with researchers. Approximately three-quarters (73.5%) of local policymakers reported that they never interacted with local researchers during the previous year, and only a small percentage (4.6%) reported interacting more than once or twice over the entire year.

To explore further, I asked how local policymakers’ interactions with local researchers compared with their desired interactions. My focus on local researchers stemmed from two considerations: local researchers are most likely to have an interest in local issues, and my prior experience had indicated that informal collaborations with local researchers tend to be both more feasible and more effective.

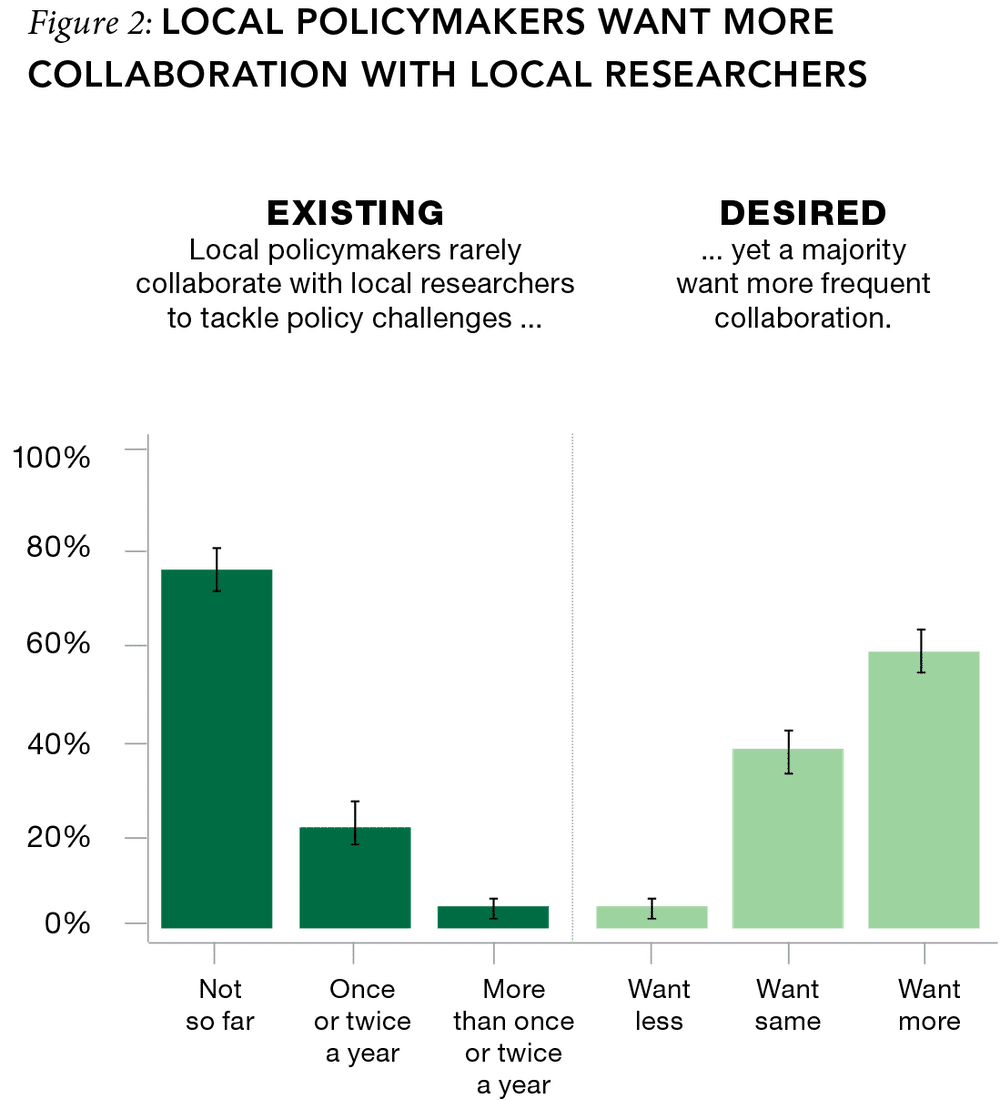

As shown in Figure 2, despite the rarity with which local policymakers collaborate with local researchers to tackle policy challenges, a sizable majority of them (57.0%) want more collaboration than they currently have, demonstrating substantial evidence of unmet desire.

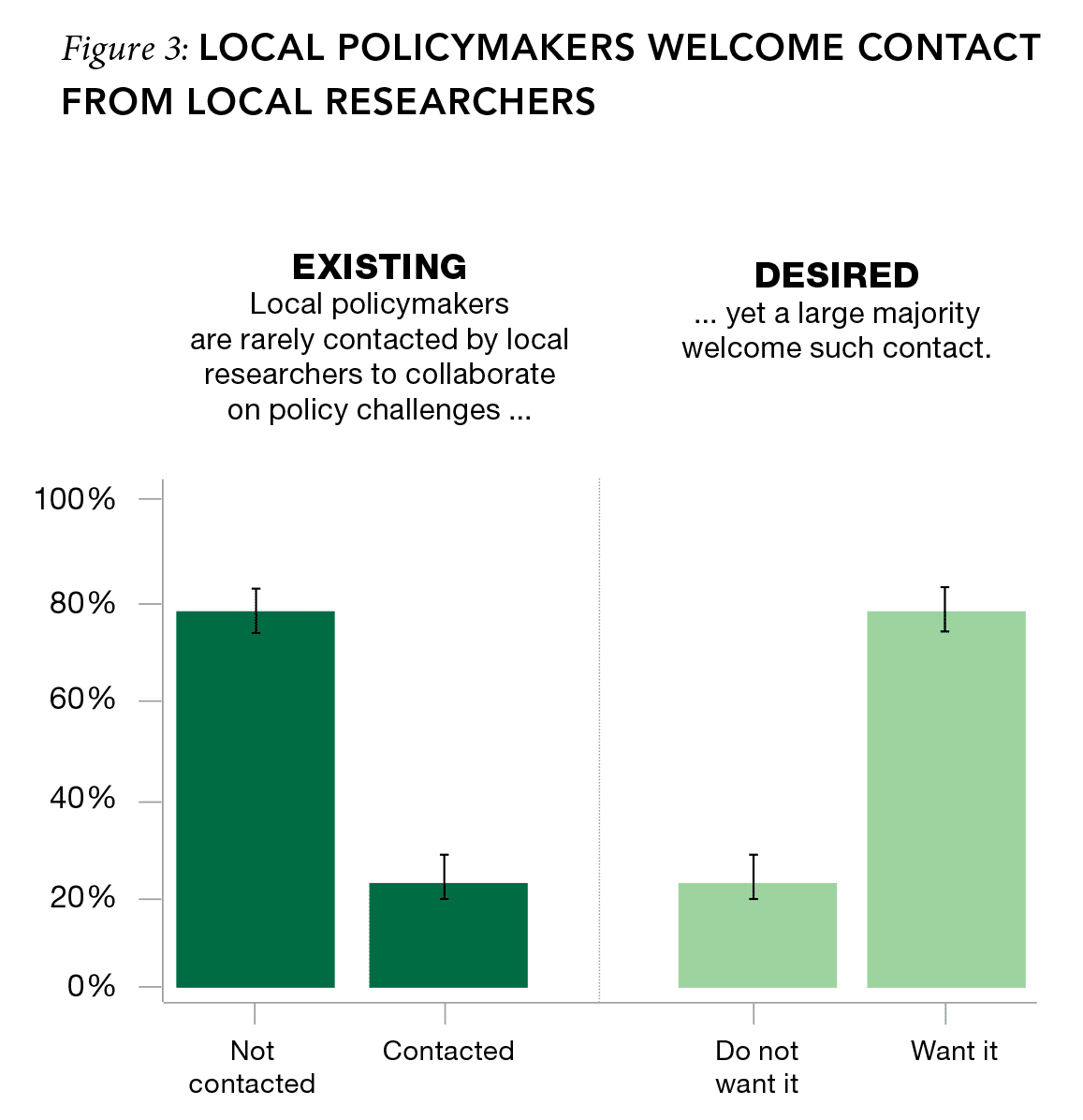

Knowing that local policymakers would like more interaction with scientists raises questions about how to meet this need. Echoing what the upstate New York policymakers told Elizabeth and me, Figure 3 shows that more than three-quarters of local policymakers (78.2%) had never been contacted by scientists over the past year, yet around the same percentage (77.6%) were open to this kind of unprompted outreach.

I also found that, although there are some partisan differences, a majority of Republicans, Independents, and Democrats desire more frequent collaboration and would welcome contact with researchers. Taken together, these patterns underscore that, amid unprecedented challenges associated with public health, climate, education, and economic development, many local policymakers want more collaborative engagement with people who have relevant technical expertise.

An opportunity for researchers

Local policymakers’ unmet desire for informal collaborations represents an opportunity for researchers who want to address societally relevant issues and impact policy. But to take advantage of this opportunity, researchers may need to adjust their thinking about what policymakers need.

When they seek to be involved in policy, it is often easy for researchers to focus on formal projects such as organizational partnerships or high-level experiences such as testifying before Congress or meeting with state and national legislators. However, local officials are both more numerous and more accessible, and what they want are informal collaborations that center around sharing knowledge.

To initiate such relationships, researchers can take the lead, beginning the conversation with a version of the prompt that Elizabeth and I used: Are there any policy challenges you’re facing in your work in which you think research would be helpful? Based on the policymaker’s response, researchers may offer to share and discuss research related to those issues or to connect policymakers with colleagues who possess relevant expertise. Past work with policymakers and nonprofit leaders found that this kind of back-and-forth collaborative exchange, as opposed to one-way dissemination of information from scientists to policymakers, has a much larger impact on decisionmaking.

Back-and-forth collaborative exchange, as opposed to one-way dissemination of information from scientists to policymakers, has a much larger impact on decisionmaking.

Elizabeth and I saw this firsthand with the local policymakers in upstate New York. They didn’t want simply a written report or a link to existing research. Rather, they wanted to have a collaborative exchange about it, so that they could make sense of what the research means in the context of their own local situation.

Informal collaborations with policymakers can also influence researchers’ agendas in significant ways. There are an infinite number of questions that researchers could seek to answer, and one of the most important tasks is choosing among them. Engaging with policymakers can help by revealing new ideas and gaps in the scientific literature. These conversations can also connect researchers to the kinds of socially relevant issues that often motivate research careers in the first place—helping to keep science grounded in pressing real-world problems.

Putting informal collaborations on solid ground

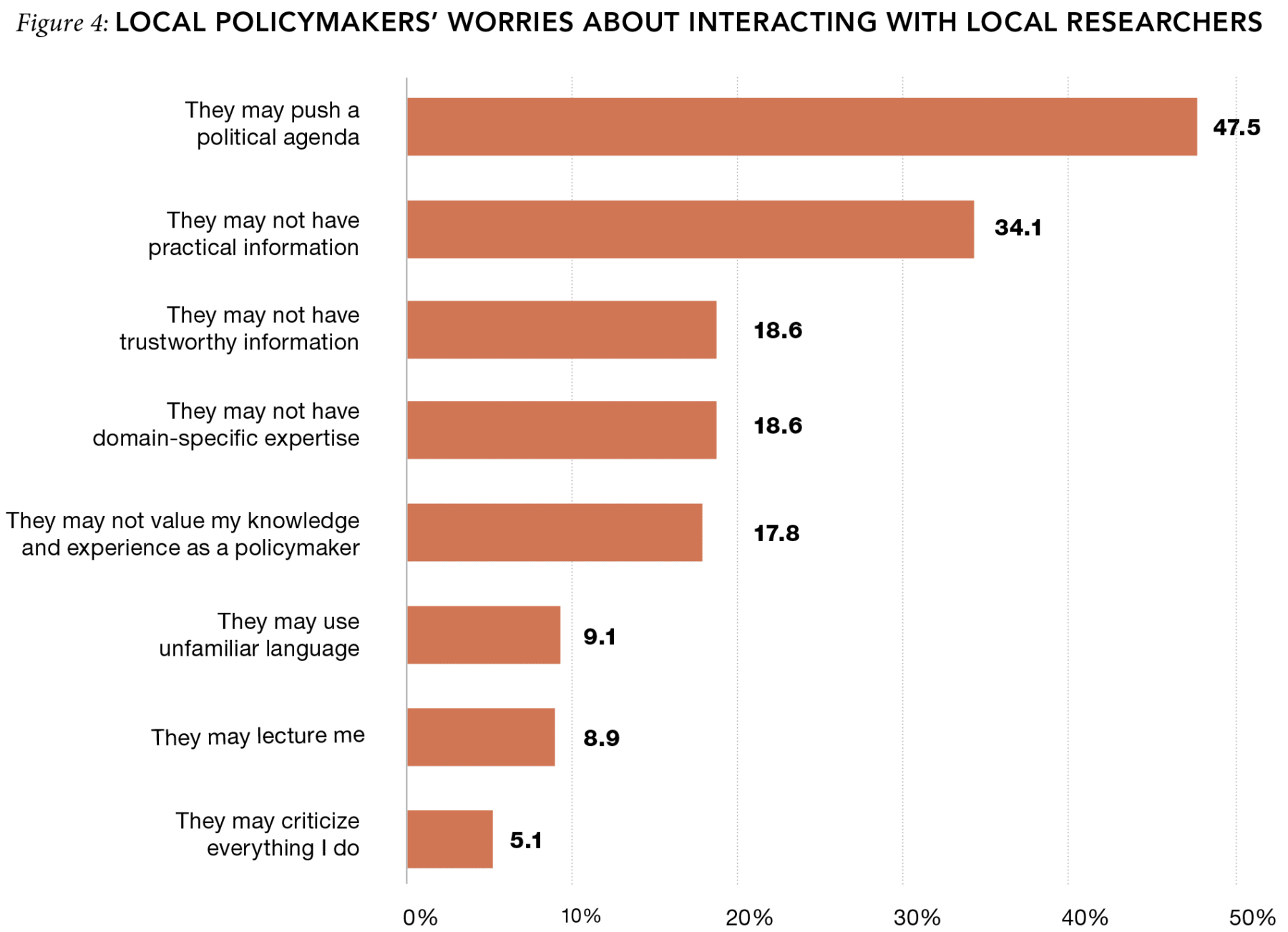

Researchers and policymakers typically start off as strangers to one another. As with any form of cold outreach, a key part of successfully initiating a relationship with policymakers is understanding the audience. In particular, researchers should work to understand concerns that local policymakers may have about interacting with them. In the survey, local policymakers were asked to indicate which (if any) of eight possible concerns they might have.

Although no single concern was shared by a majority, Figure 4 shows that some were clearly more prevalent than others. The most common concerns policymakers reported were that researchers would try to push a political agenda and that researchers would not have practical information to share.

Some of these concerns can be directly addressed by researchers, and being aware of them can help put new informal collaborations on a firm foundation. For instance, to address concerns that researchers may not value policymakers’ knowledge and experience, researchers can explicitly state that they look forward to learning from the policymakers and hearing about their work and experience on the issue.

Providing support and incentives

But asking researchers, who are already busy, to cold-call local policymakers is not always the most efficient system for creating impact. Matchmakers—either individual leaders or organizations who have a trusted reputation—can also initiate new informal collaborations. By doing this, matchmakers provide essential civic glue, especially when connecting people with diverse forms of knowledge, expertise, and experience. For example, to facilitate matchmaking on a wider scale, research4impact, a nonprofit organization that I lead, works to connect researchers with local policymakers and nonprofit practitioners. We’ve connected researchers and practitioners to discuss relevant research and evidence-informed strategies for expanding bike lanes in Wellington, New Zealand; measuring the impact of after-school education programs in Toronto, Canada; improving mental health among seniors throughout England; and increasing voter turnout among marginalized populations in Washington, DC. This kind of matchmaking is also an increasingly popular focus in other organizations; the Scholars Strategy Network, for example, is now encouraging it in chapters across the United States.

Universities and local research institutions can also play a role by providing incentives for researchers to engage in informal collaborations. Collecting and sharing data on such activities, as well as including them in performance and promotion evaluations, demonstrates that they are valued. At the Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins, where I work, researchers keep track of all informal collaborations with policymakers and practitioners. This information is shared broadly across the institute and summarized in the institute’s annual report. These engagements also factor into annual reviews, which matter for raises and promotions.

Matchmakers—either individual leaders or organizations who have a trusted reputation—can also initiate new informal collaborations.

At many universities, communications departments regularly send emails to faculty and staff sharing op-eds and media mentions. As appropriate, leaders can more widely share instances of informal collaborations with policymakers as well, which raises awareness and sends a broader message about their legitimacy and importance.

However, a note of caution: collection and dissemination of data on informal collaborations must be intentional. Unlike many other forms of policy engagement, including via Twitter, op-eds, podcast appearances, and quotes in news articles, the kinds of informal collaborations that local policymakers want often happen in private. This is not because they are necessarily secret—though sometimes they might be—but rather because the usefulness of these collaborative exchanges stems from being one-on-one or occurring in small groups. This is why colleges and universities must explicitly prompt researchers to report them and communications departments must be intentional about sharing information about them when it is appropriate

to do so.

Recognizing local policymakers’ unmet desire for science is a critical step to create viable, trusting connections between the worlds of research and policy. With appropriate incentives, as well as training for how to engage with policymakers, researchers can be empowered to contribute meaningfully to local policy issues. The result will not only improve governance, it will also strengthen civic bonds between diverse thinkers who share a desire to tackle complex problems. And at a time when some elected officials are choosing to politicize higher education, meeting this unmet desire for science is one concrete and easily implemented way to demonstrate the value of research to problems they care about, as well as to help researchers identify new and complex problems that society needs to solve.