In the Heart of the Yakni Chitto

Monique Verdin’s work seeks to understand the profound ways that climate, the fossil fuel industry, and the shifting waters of the Gulf of Mexico are changing a place that has been a refuge for her Houma ancestors.

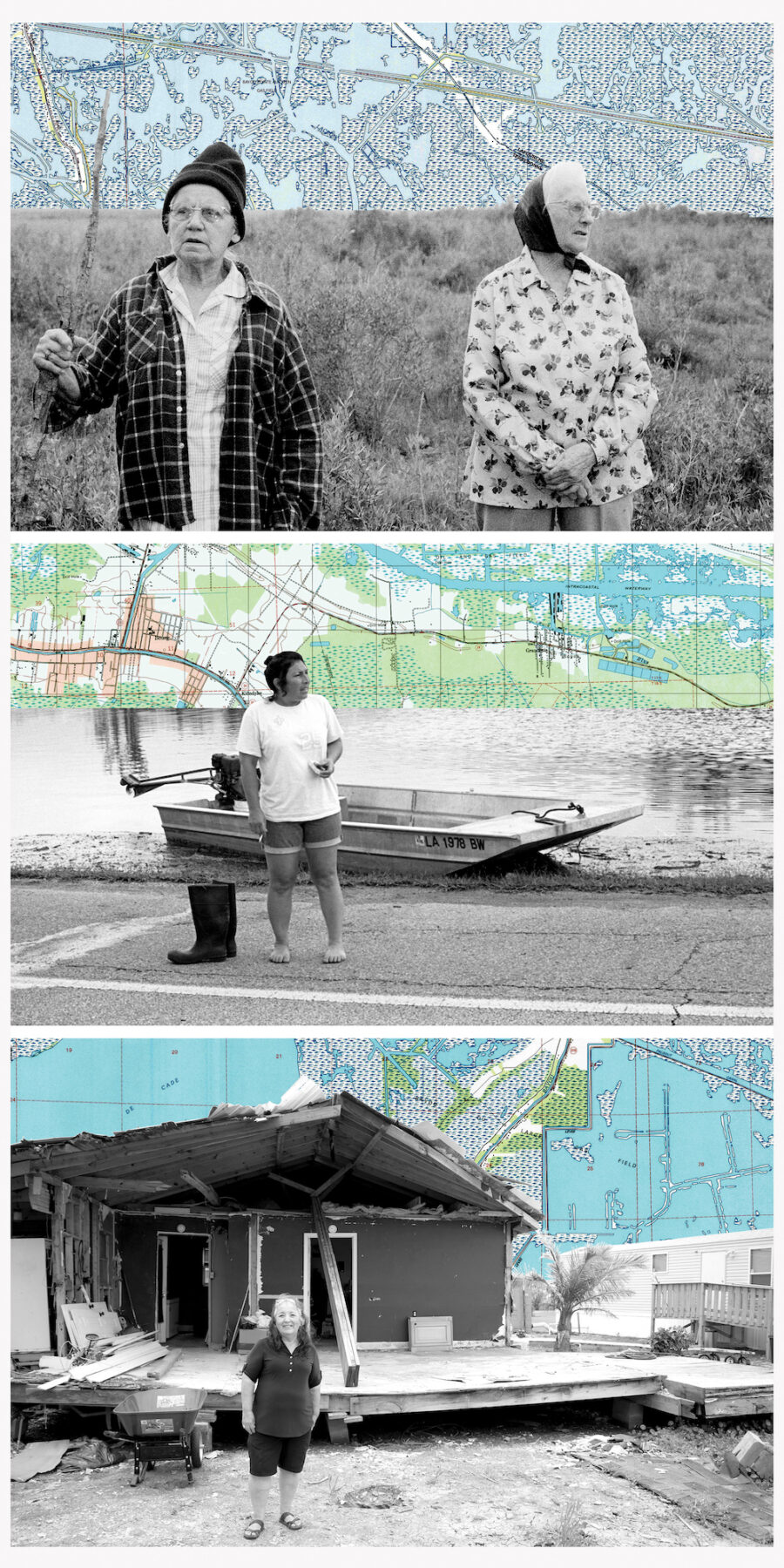

Monique Verdin began documenting the lives of her relatives in the Mississippi delta in 1998, when she was 19. That year, her grandmother Armantine Marie Billiot Verdin and other Houma elders traveled by boat to the point of land in the heart of the Yakni Chitto (Big Country) where they were born. Verdin raised her camera and began snapping photos, unaware that she was beginning her life’s work of understanding the profound ways that climate, the fossil fuel industry, and the shifting waters of the Gulf of Mexico would change the place that had been a refuge and a retreat for her Houma ancestors.

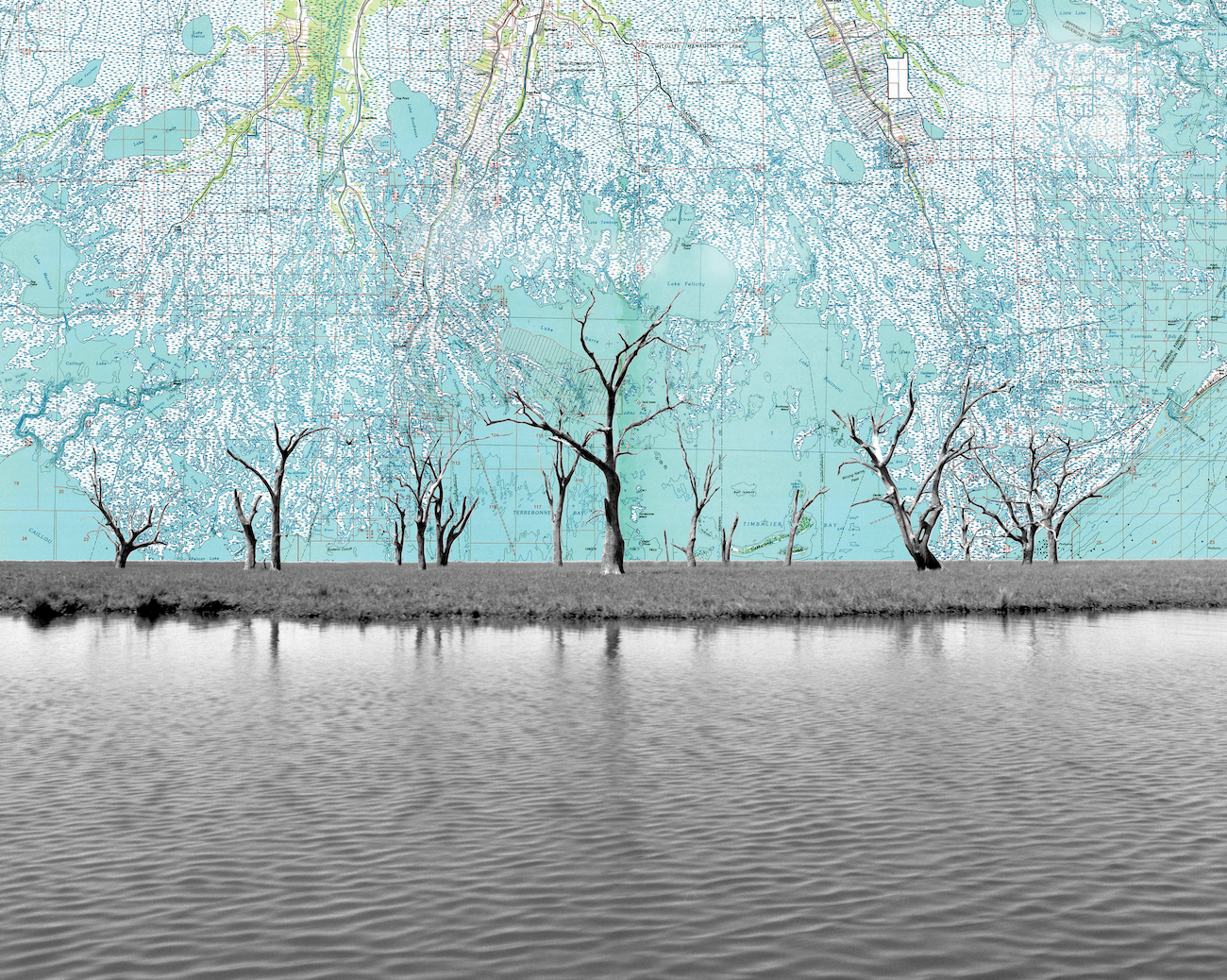

In one photo, her grandmother and her best friend are telling stories about the arrival of the oil and gas men during their childhood, in front of what Verdin calls a “ghost forest.” “There’s one dead tree and one living tree and at 19, you know, they were trying to tell me something.” She’s spent the years since trying to understand that story of home and dislocation, working in photography, film, performance, collaborative community projects, and installations. “Art has been a real gift in that it has been my teacher, requiring me to do the research and to literally frame what I’ve seen.”

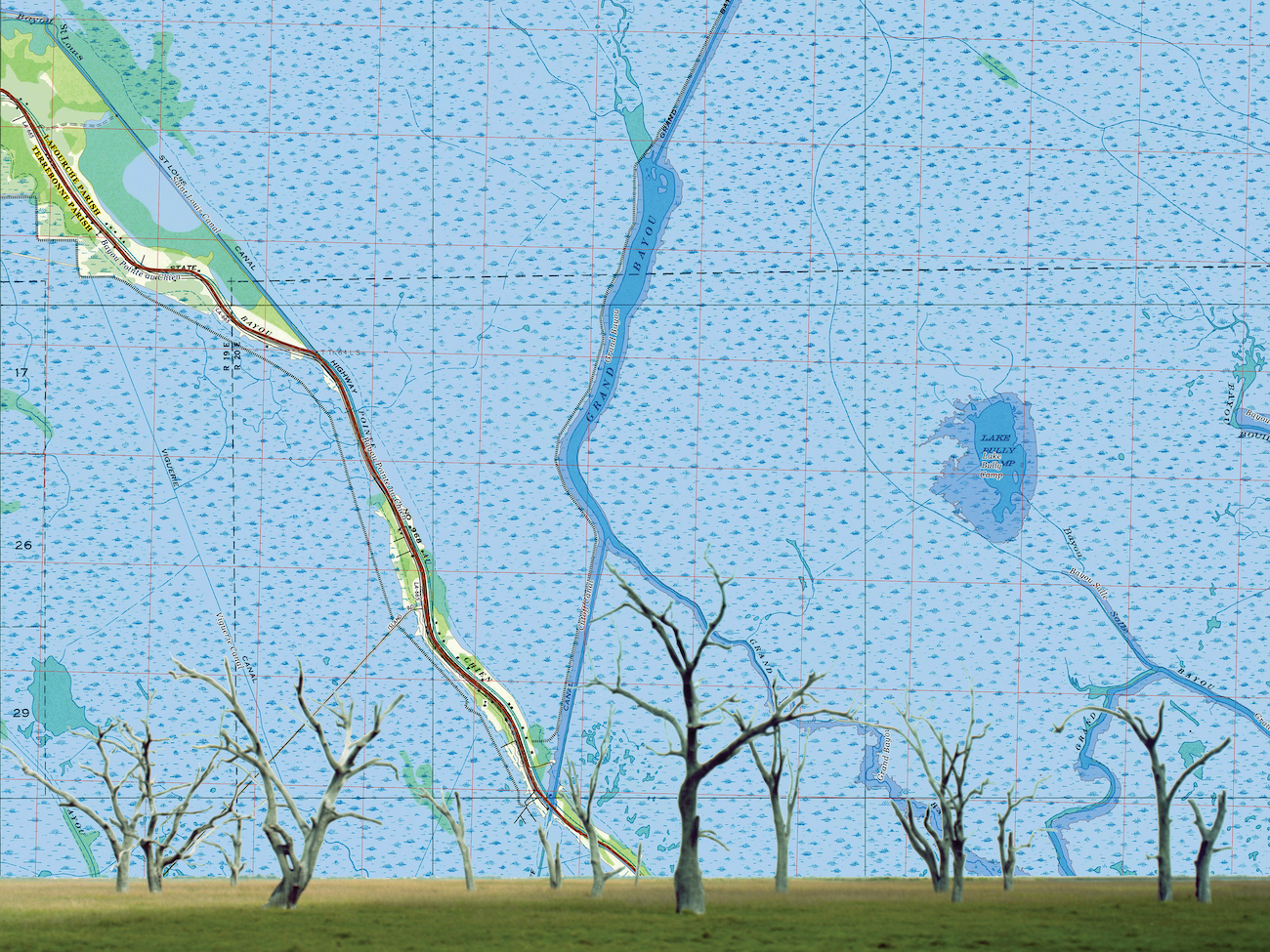

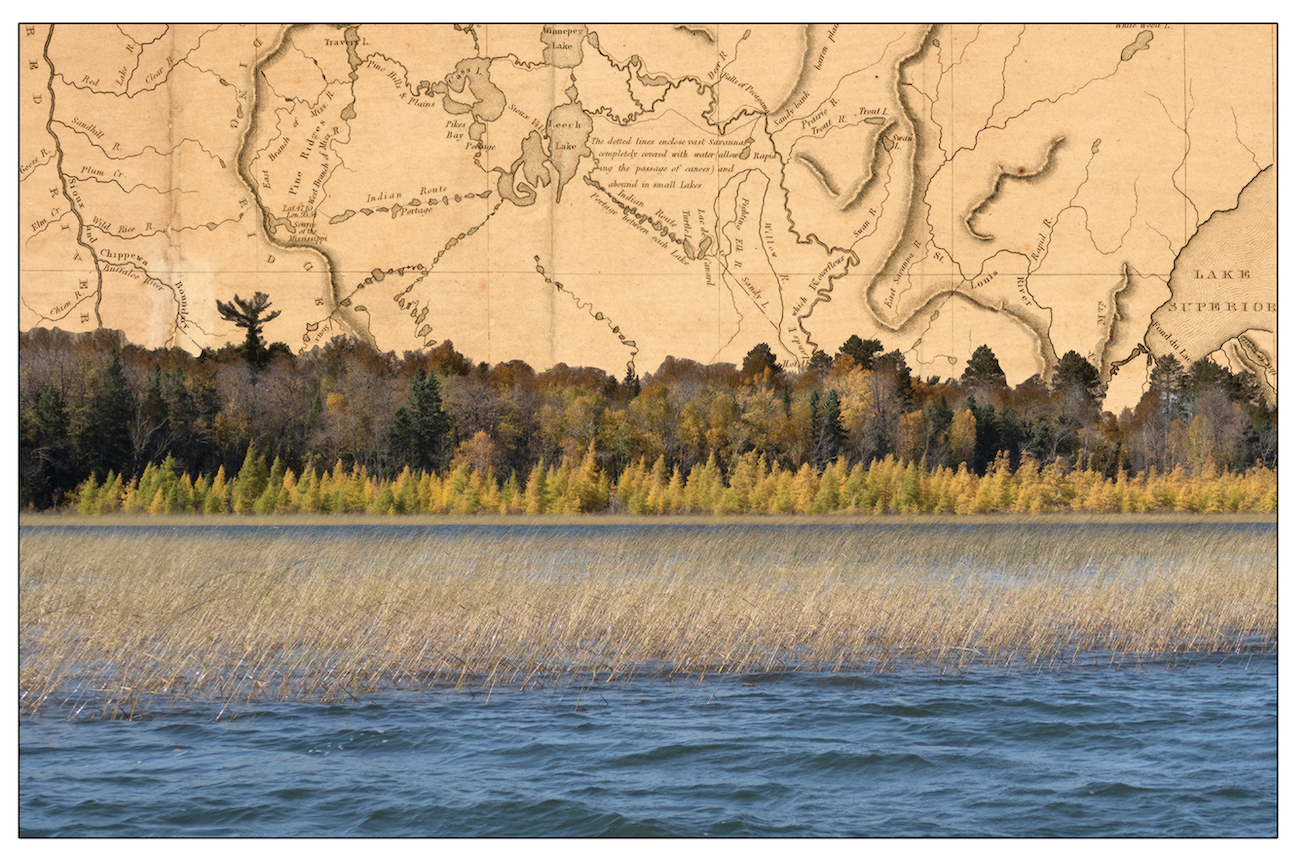

Some of that framing has taken Verdin back in time to understand how her grandparents’ generation was pushed out of their homes by the oil industry. That caused her to research the histories of Native Americans, many of whom migrated to the bayous after being forced off land elsewhere by European colonists. This layered legacy of previous dislocations is represented in the collages of Lost Treasure Maps, which show members of her community juxtaposed against historical maps. “This struggle with land losses is not new for us,” she says, explaining that understanding it brought her a deeper awareness of the future: “We’re not going to be able to outrun climate change. Anywhere we go there will be consequences. And we have the right to remain.”

When she first started making art about Yakni Chitto, Verdin thought that the story would be about rising waters and land loss. But the area was then hit by one disaster after another: Hurricane Katrina, the BP drilling disaster, flooding in chemical waste pits, more hurricanes. “I don’t think we should even call them disasters anymore. This is where we’re at,” she observes, speculating that her future—and many peoples’—will be a process of retreat and return. Collaborating with scientist Jody Deming on the Ocean Memory Project gave her a new appreciation of the relationship between climate, ocean, rivers, and atmosphere, connecting her work in the delta to a global conversation.

Recently the question of what survival means has become a focus of Verdin’s art as she works with her communities: Houma people, family, scientists, and fellow artists. What started as a look backward has become something else: “I feel like I’m downloading sci-fi information to my community these days.”