disclaimer: any preparation completed by robot is marked with *; please speak with your waiter if you desire robot-free prep, though this may modify the menu selections

please inform your waiter of any allergens

A delivery drone, painted in the garish colors of a greasy-spoon chain, was dropping off breakfast to the picketers as Noah arrived to work. The Hotel President rose black against the rising sun, dwarfing the other buildings, and it cut off the morning light, so the waiters, the valet, the line cooks were slow-moving shadows on the sidewalk. They circled an inflatable rat, patched and wilting, which loomed over passersby. Noah shrank into his coat; the drone whizzed close to his head as it boomeranged back to the diner.

He paused for a moment at the corner. He waited for his anxiety, that tremor in his throat, to ebb and watched his coworkers—and some who had joined them from sister restaurants—chat with each other, make jokes, straighten their signs when a gust of wind bent them in half. The slogans on the signs were written in bold marker on the backs of packing-box panels. human food, human labor and no robots with knives! Daniel was carrying that last one.

The foot traffic had already adjusted its pattern six days into the strike, and most commuters crossed at the intersection before the hotel rather than engage with the workers. The strikers raised their voices louder to be heard across the street on the opposite sidewalk. “They’ll come for you next,” someone yelled. They seemed like panhandlers in their loose plaids and knit hats, hair mussed in the wind, largely ignored.

When he finally pushed himself forward, Noah caught Daniel’s eyes first. “It’s today,” Daniel said by way of greeting. “Today they’re bringing in the robot.” He sniffed.

Behind Daniel, Angel shouted at a passing car that had spun mud and slush onto the sidewalk. “Fuck you too!” And then she laughed, swallowed too much of the cold air, coughed. Despite a week’s lost wages, there was still a high-strung energy sparking between the workers.

Paul and Bett were there too, the only other employees from the Middle’s lean kitchen staff and thus the only ones Noah recognized in the small crowd. There weren’t many of them to replace, when it came down to it. Paul was preparing a new sign, balancing a piece of cardboard on his upraised knee as he outlined the letters.

Daniel’s face settled into deep lines as Noah stayed quiet. “Where’s your sign, man?”

“It will only be a few days more. They’ll come to their senses. The strike fund won’t last forever.” Mr. Grose sat down on the wrong side of his desk, next to Noah. The gold logo and name of the hotel was emblazoned on the wall behind him. “When they come back—and they will, raising the question, why do it in the first place—they’ll be relieved that the hard part’s already done. By then the robot will be up and running, any wrinkles ironed out.”

He didn’t give Noah a chance to reply, as if he were afraid to leave room for any objections.

“Management prerogative, you know, by the words of your own contract. And it’s not like anyone’s job is at risk.”

“For now.” Noah swallowed after saying it.

Mr. Grose tilted his head and tried a little laugh as if to signal they were on the same page.

“Hey, chef! Noah.” Daniel snapped his fingers in front of Noah’s face. “You’re with us, right?”

“Look, Dan.” But he knew there was nothing he could say to make the situation better. Last night, he’d convinced himself there was. He’d stayed up, writing himself notes about what to say, practicing lines in the mirror while brushing his teeth.

“Grose got to you.”

He tried again. “I just said that I would get the robot up and working. This way I can make sure it doesn’t mess up the kitchen. So that there’s a restaurant and a job still waiting for you.”

Daniel flung up his hands. He looked at the line, smirked, and turned back red-faced. “Grose got to you. And you swallowed his bullshit. You know what that means, man? You’re a scab, not some saint watching out for us.”

A passing biker talked loudly into his earpiece, his words cutting through the awkward silence. “Yeah, the rat’s still there. What an eyesore.” Then there was a beeping in the alley, a truck backing up. Someone yelled, “Truck! It’s here. The delivery truck’s here!”

Noah sidled toward the revolving door of the hotel but had to wait on one of the guests to exit. She took her time, straightening the belt of her coat, and Daniel yelled after him.

“You’re a fucking coward, you know that!”

“So I’ve been told,” Noah muttered.

Angel seemed to think that Daniel’s verbal assault was aimed at the truck and began to shout at the drivers. The truck itself was still out of sight, though the sounds of hydraulics and the clatter of a lowered ramp proved their assumption that the robot had arrived. The guest stepped out, glanced at the strikers and then tugged her belt tighter, moving away and toward the boardwalk. The wind caught the dangles of her earrings and the sun glanced on them and away, there and gone. The sky went sudden gray like it sometimes does when the clouds bunch up.

“Look, Noah, you know as well as I do that restaurants like this, the luxury experience that a place like the Middle works so hard to deliver—” Mr. Grose used air quotes around “luxury experience” but Noah decided to not spend too long deciphering his meaning. “It’s a dying business model. We’re lucky if food gets delivered on time, if at all. We won’t expect to see anything from Florida or Mexico, not this month. Our margin is slim, and I can’t afford to let anything wipe out that margin. Hell, sometimes we can hardly get the hotel guests through the door, much less customers off the street.”

“I get that.”

“Well, if you understand, just say yes and we can move on with our lives.”

When was the last time he’d seen a cleaner in the building, except for the self-running bot?

Noah shifted his hands on his knees and wondered if they were as sweaty as they felt. “Just the one week?”

“You told me, when you interviewed, you told me, Noah, that this was your dream job. Executive chef of the Middle. A Michelin star. That still true?”

Noah nodded, barely.

He waited in the lobby for the elevator. The sound of falling water was piped through speakers to simulate a fountain; synthetic trees were coated with a thin layer of dust. When was the last time he’d seen a cleaner in the building, except for the self-running bot? The Middle had its own button in the elevator car rather than a floor number, a calligraphic M. He punched it, the light flickered, and he leaned back against the railing. In his head, he went over the floor plan that he’d traced out last night, as if he was heading into a recital. Mr. Grose had given him the specs for the robot and tasked him with finding space to accommodate the 4×4-foot footprint of the machine.

“This is how you get what you want, Noah. Take the help.”

Starter

panko-crusted garlic mustard root + sweet parmesan

*cleaned and tossed roots*

Noah had walked to work on his first day at the Middle, five months ago, the summer sun bouncing off car windows. He had underestimated how long it would take, but he’d also woken up too early. He hated the retrofitted buses anyways. Adding the gas engine back into a vehicle designed to be electric, to align with new mandates, resulted in a noisier, smellier experience than just buying gas-powered to begin with. But Atlantic City, like everywhere else, had to make do once electric batteries were yanked off the market.

Evidence of the last flood, the one that’d made people question whether the city would recover, was clear if you knew where to look. The trees were too young, saplings surrounded by deer-resistant fencing. There were widening cracks in the sidewalk where weeds found purchase with their spiny stems and too-large leaves, aggressive and green. Between jobs, he’d taken classes for a certification in foraging, and he took a certain amount of pride in identifying the edible species as he walked. He imagined softening the rigid plants, blanching their leaves, finding the sweet or bitter bite to offset the mildness of engineered food products.

There was a thread on the buildings, a faint drift of dirt and salt, that traced its way along the floodline, a discoloration of ground-floor windowsills and blinds. The cement between stones was chipped and pocked; signposts swayed a bit more than they used to. The smaller casinos had abandoned their ground floors, unable to afford insurance premiums ratcheted up by climate change. This left wide, dark, unoccupied spaces on display through glass doors and an eerie neon glow above. Dead and rusted cars had been shoved into small alleys, off the road but not quite out of sight.

Against all of this, as the city opened to the boardwalk, the Hotel President towered. There had been another hotel of the same name there in the late ’70s, almost 60 years ago; this new version had been constructed with help from a state revivification grant. The Middle, Noah’s restaurant now, catered primarily to the President’s guests, plus some long-term residents in the penthouse suites. The dining room was at skyscraper height, so you could stare and stare and not see any end to the ocean from its windows, just eventually the sky.

He’d thought a long time about what menu could match that view.

Salad

dandelion greens + violets + sunflower oil

*minced greens and centrifuged oil*

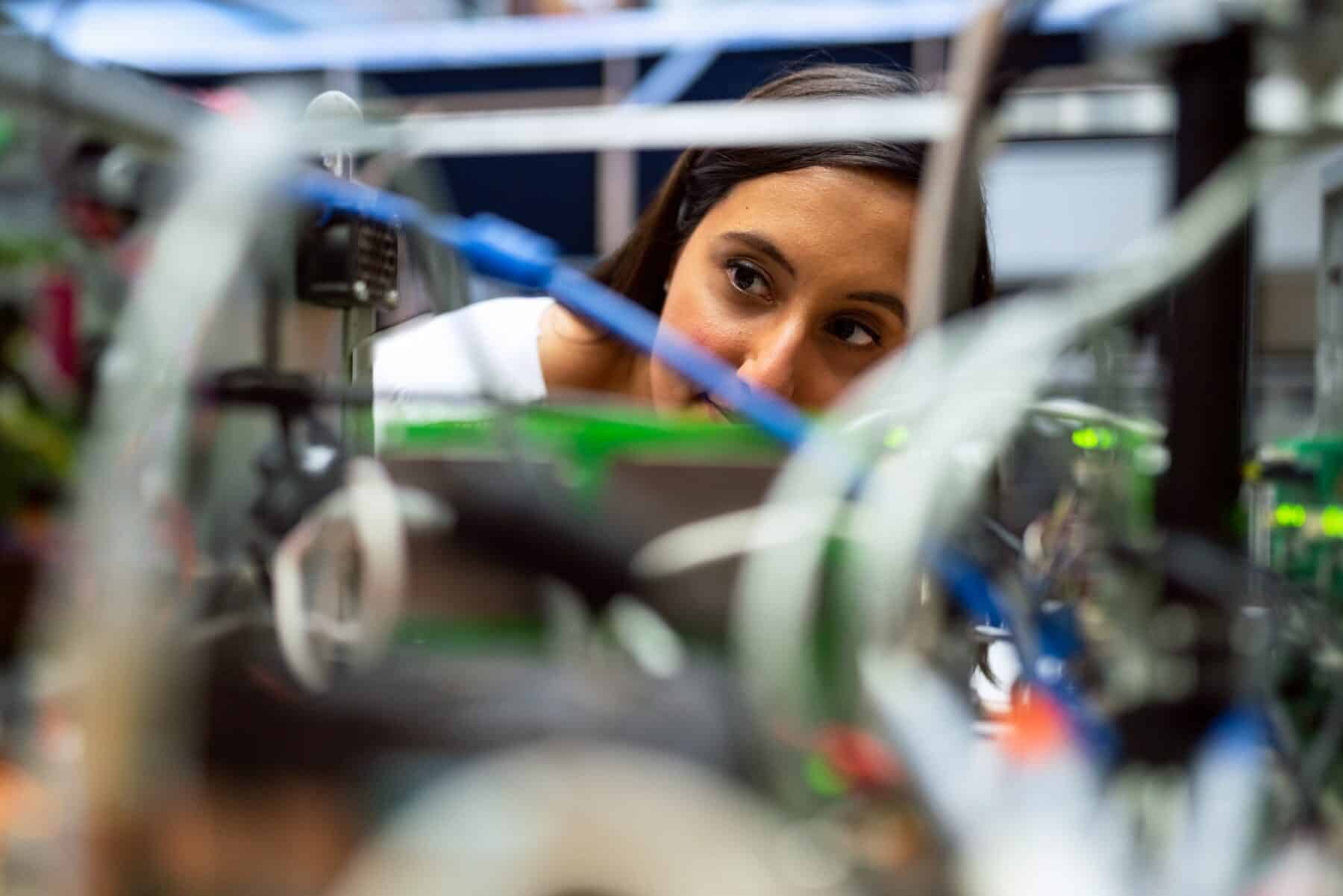

The robot cook was plastered with warning signs. The techs didn’t seem to mind those as they struggled to reach the outlet with the too-short power cord. Noah studied the signs while he waited. The usual cautions about electrical devices—a stick figure splayed into angular spasms and a flying lightning bolt—and a note about sharp blades. He studied the cook to see where these blades might poke out.

It had two skeletal arms, metal and wire, with galvanized claws at the ends. It held these tucked up into a cavity in its angular chest. The overall effect was a large metal box, with the flimsy look of a heating duct, crabbed appendages origamied in front. The box tapered to a swiveling pedestal. Some designer clearly had the bright idea to place the power and active lights like two tiny eyes above the arms. Its name, printed across the packaging in a retro-futuristic font, was Su-Chef, which seemed inappropriate for the industrial look of the machine. Noah hoped its arms were long enough to reach the prep counter.

Its name, printed across the packaging in a retro-futuristic font, was Su-Chef, which seemed inappropriate for the industrial look of the machine.

Sweat beaded on one tech’s forehead when he finally gave the Su-Chef “quick start” pamphlet to Noah. “It’s all in there.” He gestured with an oily finger to the QR code. The rest of the pamphlet was a splashy ad for the company.

“That’s it?”

“Yep. Sign off and we’ll get out of your way.”

Noah stood alone in the kitchen, Styrofoam sheets and packing peanuts bunched around his feet. Su’s power light blinked as it booted up. Noah expected it to speak to him, offering a greeting or instruction, but it did not. It thrummed, like an overworked refrigerator.

After he’d moved, his mom and sister insisted on visiting. They’d helped him buy sheets and lug the illegal AC unit out of the window and to the dumpster. His window overlooked that dumpster and the fresh air could’ve been fresher. But they hadn’t stayed in the apartment much during the visit. They’d gone down to the boardwalk and fed the gulls the burnt ends of their fries. “You’re saying these aren’t made of potatoes?” his sister asked with her usual note of put-on disbelief. “They still hit the spot.”

The gulls ran uncomfortably close for those scraps, aggressive with each other and any observers. Noah dusted the salt from his fingers and tossed the paper bag, moved back toward the boardwalk. The sand shifted under his sneakers.

“I feel like I could do anything here,” his sister said, planting her feet. It was early, so there were few passersby. A teenager roused themselves from sleep on a bench when she yelled out over the waves.

She lectured Noah on the way back to the bus stop. “You know how hard it is to yell? To really yell? To overcome that inhibition?”

Mr. Grose had given Noah three days to reorg the kitchen around Su before lunch and dinner service started up again. But the owner hadn’t addressed who was meant to seat diners or take orders, much less wash dishes and prep food. In fact, he hadn’t really communicated with Noah since their talk in his office. “I’ll be your first customer when you’re back online,” he’d promised.

Given the way people now avoided the entry to the hotel, Noah wondered if Mr. Grose might be the only customer. Hotel security had set up a temporary barrier to clear the path to the door, but Daniel and the others jostled against it as they composed chants on the fly. Cook real, Eat real and Ratatouille, not robot-phooey. They were cheesy lines out of context, and in a different timeline, he and Daniel would’ve mocked them mercilessly. But in this reality, Daniel just shouted louder, the veins in his throat popping, when Noah arrived to work.

“Don’t blow it all, Mom,” Noah’s sister teased at the blackjack table. Their mother was the picture of practicality—short-cropped hair, stud earrings, sunglasses tucked into the collar of her shirt.

“Just your inheritance, honey.”

The dealer was a robot here, a fancy slot machine with a tinny yes/no routine. In red letters across a screen on its front crawled the dinner specials for the evening. This was one of those dimly lit second-floor establishments, and it hurt Noah’s eyes to look at the ad for too long.

An app on the proprietary tablet allowed him to upload signature recipes to Su; other basic kitchen tasks had been preprogrammed. The robot could analyze a picture of a completed dish, cross-reference the dish against common ingredients with 90% accuracy, and submit orders to suppliers—or find new suppliers at better prices. It could chop, dice, mince, and then weigh what was chopped, diced, or minced to minimize food waste. From these processed ingredients, the Su-Chef could make determinations about whether to increase or decrease amounts in the recipe based on the acidity or spiciness of the individual ingredients through on-the-spot chemical analysis. It was heat- and cold-resistant so that it could prepare food at the ideal temperature, not merely the range of temperatures tolerated by human chefs. It could provide suggestions based on ideal palatal variety for those guests who wished to complete a taste analysis in their rooms before dining.

It was heat- and cold-resistant so that it could prepare food at the ideal temperature, not merely the range of temperatures tolerated by human chefs.

This is what Su’s online manual had outlined to Noah the night before, as he absently ate the soy ice-cream (“frozen dessert”) his sister had left in the back of his freezer. He’d had to scrape off a layer of freezer burn. In Middle’s kitchen, under the fluorescent lights, he was less optimistic.

“And yet tossing leaves in vinaigrette …” He muttered under his breath. “That we’re having trouble with.”

Su suddenly spoke and Noah jumped back a step, hitting his hip on the counter. “A suggestion?”

It took him a moment to parse out that the robot was requesting permission. Its voice was oddly soft, but the words were enunciated so clearly as to be unmissable.

“What?”

“A suggestion?” It mistook his own question as misunderstanding.

“Yeah, go for it.”

“Avocado oil would complement the violets.”

Noah removed the bowl of dandelion greens from Su’s claws. The oil dripped heavy and glistening down the metal.

“And can you make avocados for me, Su? Because I haven’t seen one of those in a grocery store for five years now.”

“A new software update is released on the fifth of every—”

“The answer is no, Su.”

Soup

black bean reduction + corn + poblano-toasted crostini

*shucked and blackened corn, toasted bread*

The Middle had never been particularly busy. Noah had described it to his mom as selective. There were a few regulars from the penthouses, but often they had food delivered to their suites rather than sitting in the dining room. Hotel guests rarely made reservations but expected prompt service. Walk-ins were often tourists who wanted a break from the casino glitz. And then there were the dates, the anniversaries, the marriage proposals in front of the spectacular view, the celebrations when people wanted to impress others with the dollar amount on the check.

During Noah’s cold open with Su, there had been only one guest: A woman in a windbreaker who ordered soup, only to deliberately spill it over the table and floor. She was, he learned later, a friend of Bett’s. Mr. Grose was apparently unruffled: He held an enthusiastic press conference in the lobby—since the sidewalk was otherwise occupied—and did a few interviews on local radio stations and podcasts. He made calls to the casinos and dropped a word in the ears of restaurant critics.

“The first prestige kitchen in Atlantic City,” Mr. Grose boasted, “with a robot to match. This isn’t a burger-flipper; this is a curated experience.” A news reporter had turned to ask Noah a question as they toured the kitchen, but he’d already ducked out the back.

“This isn’t a burger-flipper; this is a curated experience.”

Someone threw a paint can at the news van, leaving a streak of red across its gray side panel. One of the picketers was arrested for the vandalism, a dishwasher from another restaurant who had joined the strikers on his own break. When Noah found out, he made an anonymous donation to the bail fund via the state’s official crowdfund app.

“The menu is prix fixe this evening,” Noah informed a guest from the seventh floor. “No custom requests. I’m shorthanded tonight.”

“But you have the robot chef, yes?” She looked over the menu that he had printed in the back office that morning. “The clerk out front was raving about it.”

Noah nodded, struggling to remember if he’d ever met the receptionist. “Newly installed.”

“I was in a restaurant on the West Coast which had just installed one too. Fabulous.” She traced down the wine list with one lacquered nail.

“Are you traveling for work, then?” Angel and Paul were so good with small talk. They treated the whole crew to drinks when the tips were good.

“Not if I can avoid it.” She laughed and then settled on a glass of water—“with lemon”—until she made up her mind. Noah didn’t understand the joke, and so he shuffled back to the kitchen. Pick up your feet, Noah! He wondered what it might be like to retire to a little house upstate where he could cook for himself alone. The thought surprised him. For as long as he could remember, he’d watched the diners’ faces and forgotten to eat himself.

The lemon was shriveled and small, but he pared off a thin slice. Su stood silent with its knife gripped in one claw. “Your turn next time,” he told it.

It began to recite to him. “Knives are a leading cause of kitchen accidents. It would be safer—”

For as long as he could remember, he’d watched the diners’ faces and forgotten to eat himself.

“Enough.” He had programmed that as the shut-off word. Su dropped quiet with startling quickness, leaving the quiet ringing.

As he curled the lemon over the rim of the glass, it tried again. “Given the dryness of the lemon, two slices—”

“Enough.”

“You’re always shuffling. Walk like a man. Walk with confidence.” Noah’s dad watched him moving around the kitchen from his cushioned recliner, the springs of the chair creaking.

The local news, with the AI anchors, played at a volume that no one could actually hear.

He ignored his dad, as he usually did. Mom would be home late from her shift at the hospital. “I’m going out on the back porch to shuck the corn.”

Barefoot on the splintered wood, Noah let the sun-warmth from the day’s heat travel up his legs. The silk stuck to his fingers as he folded back the husks and snapped the ear off clean from the rest. The cicadas were singing in the late summer light. The cobs rolled back and forth on the warped cookie sheet as he stacked them to one side. Sweat glistened in the pits of his elbows.

When Noah returned to the dining room, he saw that Mr. Grose had seated himself at a corner table and was staring out the wall of windows, pretending not to watch.

“We’re getting some good buzz,” he said, after Noah had dropped off the water with lemon. “People are curious about the chef and his wonderful cooking machine.”

“You’re eating in with us tonight, sir?”

Mr. Grose waved his hand dismissively. “Naw, I want something I can sink my teeth into. I just wanted to stop by and see how it was going.”

“It would help if we had the wait staff. And the prep cooks—”

“Noah, Noah.” There was his name again. “Don’t worry about that. What’s on the menu tonight?”

Noah wiped his hand on his apron. “Main is glaciated beef cubes if you’re looking for something to chew.”

Mr. Grose grimaced, just a corner of his lip lifting. “That reconstituted stuff makes me queasy. I’ve got steaks upstairs. Flown in from Japan. Assuming you have some of your weeds on the side?”

Noah coughed, like he’d swallowed wrong. “Served with pearled farro and wild carrot.”

“You know, I always used to think this farm-to-table, foraging thing, the whole movement, it was a bit of a scam. But damn if it hasn’t come in useful.”

Noah felt the heat rise up the back of his neck. “If that’s all, sir?”

“Yeah, yeah, go do your thing. My compliments to the robot-chef.” He raised his hand to mime a toast.

“Aw, thanks, honey.” His mom always spoke quietly when she got home from work, like she’d used her voice all up. She sat for a moment, contemplating the plate he’d saved for her. The chicken was mostly gristle, but there was a salad of dandelion greens he’d picked from the backyard. There was the corn and margarine and salt. “I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

“My compliments to the robot-chef.”

Two more tables came in over the course of the night.

One couple, well on their way to drunk, had come from a casino where the robot cook had been advertised in the digital crawl of one of the dealers. “We’re spending big tonight anyways,” one of the men nearly yelled. His collar was undone, his tie loosened, his cologne aggressive. They laughed at the violets in the salad. “I can’t even taste them,” his partner snickered. “Is this what purple tastes like?”

Noah was used to bracing himself against the swinging door coming at him, kicked by one of the waiters. But there were no surprises tonight. The dishes piled up in the sink. They must have more forks than he could find. And since when did Michelin-star restaurants advertise at blackjack tables?

Su knew that table two was drunk, though Noah hadn’t realized the robot had been hooked into the cameras. It suggested a bolder flavor profile for their dishes. “It’s a fixed menu,” Noah responded. He imagined the robot shrugging. The corn for their soup was more burned than blackened when Su flipped the pan and dumped it into the salt bath.

“I can’t serve that,” Noah said. “I can’t serve that.” He threw the whole bath into the sink.

“A waste of food,” it reprimanded him. “Loss amounting to—”

“Enough!”

Main

glaciated beef cubes + pearled farro + wild carrot

*chopped carrot and refrosted beef*

The bus stopped only a few blocks from the hotel, but Noah still barely made it to work on time. He walked slowly, his stomach sinking in anticipation of crossing the strikers. A cop car rolled by, the men inside clearly monitoring the activity on the sidewalk. It was raining, heavy and unrelenting so that it ran in streams off his umbrella. His pants were wet to the knee.

“Robot keep your bed warm at night?” Daniel’s voice was tired, which took a little of the sting out.

The hotel awning was dripping on the strikers. They looked fewer in number, huddled close against the wall. Noah stopped and met Daniel’s eyes. This shut him up for a second as he waited for a response.

“What do you want me to do, Dan? If I don’t keep things running, then we’re all out of a job. The restaurant closes.” It was like rote memorization now.

Daniel laughed but it wasn’t friendly. “You must think you’re pretty indispensable. Maybe you haven’t seen the latest write-up yet? Headlining on the Restaurant Revue?” He looked over his shoulder and the others sidled up to join—Angel, Paul, and Bett. Noah’s guts cramped up, remembering the lukewarm praise of the other reviews to date, almost more insulting than an outright pan. “Besides,” and Daniel’s voice dropped like he wasn’t playing anymore, “does it look like we have jobs now?”

“If I don’t keep things running, then we’re all out of a job.”

“If you don’t give this up, Grose is going to have you all arrested. We’re losing customers.”

“Legal right to assemble,” Angel muttered.

“You know that doesn’t matter.” Noah jammed one hand in his pocket and readjusted his grip on the umbrella. The rain was loud, hitting the awning and swirling under the tires of cars passing. He thought of the flood, the line of dirt on the buildings. “You think I’m dispensable? You should see Su; she dices like a maniac, faster than you ever could.” Noah caught the she as the pronoun left his mouth, tried to bite down on it.

“Fuck you,” Paul spat. But Daniel got a look on his face, like a kicked puppy, that scared Noah. He almost vomited on his shoes.

“Thought that was the robot’s job,” Noah said. He spoke too fast and ruined the delivery. He felt like shit when he turned his back and went into the lobby.

The sound of the rain was muted inside, layered with the simulated fountain sounds. The elevator was out of order. An older woman waited in a chair, one hand on her walker. “They say it should be fixed soon.” She shrugged. She wore pearls with her sweats and large rings on her swollen fingers. They looked painful.

“Name’s Dan. Or Daniel if you’re Mr. Grose. Welcome to the kitchen.” It was a pale man with too-long hair who stuck out his hand. Noah took it for as little time as he could. He’d never felt comfortable with handshakes. Dan didn’t seem to mind. “I’m your sous-chef and line-cook all in one. That’s Angel out front. Imagine you met her coming in. She’s the hostess. We have Bett here, who takes care of the dishes and busses on occasion. And this is Paul. He’s the waiter. Our one and only.”

Noah felt the need to take a sympathetic breath. He wondered if Dan had wanted his job.

“Nope,” Dan said, as if he could read the question on Noah’s face. “And I don’t have the cuh-linary background for it. Worked my way up from fast food.”

“Okay.” Noah glanced over the kitchen, which was small for a restaurant with the Middle’s prestige—or wannabe prestige. “I’m Noah.”

“Didn’t bring any flood with you, did ya?” Bett chimed in from the sink. They seemed pleased with their own joke.

Su had started the prep before Noah even stumbled in from the service hallway. The lights were low in the kitchen and her power and active lights gave her a fuzzy halo.

“Are those the carrots?” he asked, running a finger through a heap of shredded root.

“No carrots today. None delivered,” Su answered. She whipped the knife back over the cutting board and Noah yanked his hand back. The dicing sounded like hail or bullets.

“What are you cutting then?”

“Rutabaga. Meets the same palatal dimensions.”

He nibbled on a shred. “And we have it on hand. So that’s a plus, I guess.” He took another bite. “I think this would be better in discs, though, if we’re using them.”

“Already shredded.”

He turned away in frustration rather than find himself in an argument with the robot. He clicked on the bank of fluorescent lights. The kitchen sprang, white and metal and bold, out of the shadows. Su’s torso looked washed out, eyes fainter now.

“Have you read this morning’s review?” He sometimes consulted Su for things like the weather, which felt at odds with her arms chopping and dicing. She was quiet as she searched, arms bent and uplifted, untiring.

“From the Restaurant Revue?” She did not turn to look at him, but continued to stare at the dropped cabinets. Rather, she didn’t look anywhere.

“Is it bad?”

It occurred to him that Su never used a first-person pronoun.

“Unknown.” It occurred to him that Su never used a first-person pronoun. He wondered if that had been explained in the tiny paragraphs at the end of the instruction manual.

“Read it out to me.”

The Hotel President is as it sounds. Big and impressive as a building. And the Middle, clever as it may be with its titular allusion to a safe bet, plays it too safe. The atmosphere is predictable at best, though if one desires a seafront view, it offers a nice-enough one. And thanks to its robot chef, the food is the most precise I have ever eaten. But do we crave precision in our food? The foraged greens were rustic in their appeal, a choice that may have felt artful in human hands, rather than a necessity in a moment when cuisine must bow to the vagaries of supply chains. The beef cubes, though they were aggrandized in the menu description, only reminded me of childhood meals in which we did not question that we would always have meatloaf. The new method of cooking—glaciation—was capably done but it feels like food meant to be looked at rather than eaten, preserved on display for posterity. The rosemary syrup over juniper berries was my favorite dish of the evening, as it is easy to forget the artificial when faced with the ripeness of a berry. Berries will always remind me of summer. But their freshness clashed with an accompanying drop biscuit that did not look, thanks to robot hands, as if it had been dropped. Ultimately, this reviewer asks herself why she would go to a restaurant that costs upward of $200 per plate if she can eat something created through the same mindless, mechanized labor at the fast-food drive-thru. The Su-Chef claims to revolutionize the dining experience, but did it need reinventing?

“Enough.”

Su stopped abruptly, though the review had already come to an end.

“If you’re learning, Su,” he said slowly. “That was bad.” He breathed in and out. It didn’t hurt as much as he thought it would.

“Data received,” she answered.

He looked at her and he thought of Jetsons reruns and automats. “You’re putting people out of a job.”

It didn’t say anything. Its active light blinked, and it spun a knife in one hand as it switched tools. He could go over and pull its cord from the wall. He didn’t.

“Fixed menu today?”

He swallowed and cleared his throat. “If we’re going to get rid of those rutabagas.”

Dessert

Juniper berry + rosemary syrup + drop biscuit

*mixed batter and reduced berries*

There is no office to pack up when you leave a kitchen.

Noah folded his apron and left it on the counter; it was Middle property. He ripped up the menus he had printed, just for the catharsis. There was a closet in the service hall where he hung his street clothes, his hoodie and ball-cap. The hoodie still smelled like the kitchen; he hadn’t washed it since he’d moved to the city. His sister would rag him about that. He decided not to think, yet, whether he would move back home.

Every kitchen has its own smell; theirs was of water condensing on the leaky fridge and grease that had stained the backsplash over the stove. Both fridge and backsplash had been there longer than him.

But he could inventory that kitchen, even years later. Down to the scraped-up Teflon skillets and exact number of plastic spatulas.

“She called the Middle soulless, generic.” Mr. Grose almost growled. “Do you know how much time and money I’ve sunk into this place? Might as well have just gone and gambled it away like everyone else in this city.”

He looked at Noah.

“Mechanized and mindless, chef. What do you say to that?”

Noah had not been offered a seat. He stood while Mr. Grose glared across his desk.

“The menu was mine, sir. I took a lot of time and care with it. But I think the reviewer was too fixated on what her cook looked like to really think about the food. I could have prepared it myself, but if she thought a robot made it, she was going to hate it.”

“That robot is an expensive investment. So I can’t accept that.”

“I know, sir.”

Mr. Grose stood up, hands on desk. “Do you know, chef? Have you ever, in your entire life, handled that sort of money?”

Noah shook his head. He knew what was coming, and he was already tired of the conversation leading up to it.

“At least you admit to it. That the menu was yours.”

Noah blinked and waited.

“Maybe it’s not the robot that has the creativity problem.”

Noah folded his arms. “You’ll run a kitchen with no staff?”

“Mechanized and mindless, chef. What do you say to that?”

“Well, Daniel has been whining down there long enough. Maybe he’s ready to earn some money.” Mr. Grose looked down at the blotter on his desk and Noah wondered the last time someone had written in ink there. “We’ll have your severance check in the mail, Mr. Herrik.”

Noah turned and left without saying goodbye. The world—the deckled wallpaper, the inset sconces—felt distant and smeared. But the Hotel President had always felt a little unreal.

His farewell to Su was brief. “Good luck,” he said. It didn’t answer. He rode the elevator down to the lobby. It was quiet; the sound system was down. He lingered for a moment and listened to the phone ringing at reception, shoes on the tiles, echoes under the vaulted roof. He watched the door. He couldn’t hear any chants.

Paul wasn’t on the picket line when he finally went out. “He had a kid emergency,” Angel said. She looked tired, her skin washed out. “Sorry you got fired.” She seemed to mean it. She’d always been good at holding more than one emotion in her at a time.

“Dan.” He paused. “Daniel. I’m hoping we can leave on good terms at least.” He held out his hand.

Daniel stared at it. The sun had moved overhead and the President no longer cast its long shadow. It was bright and clear. Noah could hear the waves and the gulls screaming. He could go for some fries.

“That review really tore you a new one, huh?” Daniel looked at the sidewalk and then back up. Then he laughed. “Sure, man.” He shook Noah’s hand. “Maybe the robot will nuke Grose’s ass.”

Angel laughed and Daniel grinned. And, like they used to, they waited for Noah to decide if he liked the joke. Bett, in the background, was lecturing a passing tourist about the strike. Noah decided not to tell Daniel that Grose would be asking for his help next. He told himself that he knew what Daniel would do anyway.

It was a perfect day for a stroll down the boardwalk. “I’m going to grab some lunch. You all want something?” There was a clamor of orders. Someone tucked a few dollars in his pocket.

The wood of the boardwalk drifted gradually into sand, as if the boards had disintegrated with time and water. Sand slipped into his shoes. The waves were gentle, leaving seaweed curled on the shore amid bottle caps and clouded glass.

The fries were hot. Noah juggled them and foiled hotdogs from hand to hand as the vendor swore at the cash and fumbled with change. The kiosk had only just opened for the year, and its faded paintings of cotton candy and popcorn had seen better days.

Noah couldn’t tell the difference between the extruded chickpea fiber and potatoes in the fries, just like his sister had said. They tasted like grease and salt as he ate a handful, staring out over the beach. He saw sea and he saw sky and that was it.