To Support Evidence-Based Policymaking, Bring Researchers and Policymakers Together

Scientists frequently bemoan the gap between science and policy, seeing the slow adoption of scientific and technological solutions through research-informed policy as missed opportunities to help people and benefit society. Yet if researchers want leaders to make evidence-based policies, they must develop ways to support the use of research in policymaking that are themselves based on evidence. This sentiment has been a driving force for our work over the past decade, developing and testing strategies to support evidence-informed decisionmaking through the Evidence-to-Impact Collaborative, a Penn State University research center.

We found early on in an experimental study of over 400 community leaders that when different types of people work together on shared policy problems, knowledge about evidence-based practices improves. We brought together leaders working to reduce youth substance abuse from schools, law enforcement, cooperative extensions, and parent organizations. Using a model called PROSPER (PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience), we engaged with participating leaders and tracked their knowledge and use of evidence-based practices over half a decade. The type of structured, trust-building engagement embodied in PROSPER led leaders to be twice as likely to identify an evidence-based intervention as those in the control group, and nearly three times as likely to understand how to implement such interventions properly. Subsequent work found that, by bringing together community leaders, the PROSPER model could in turn prevent youth misuse of opioids, cannabis, alcohol, and other drugs.

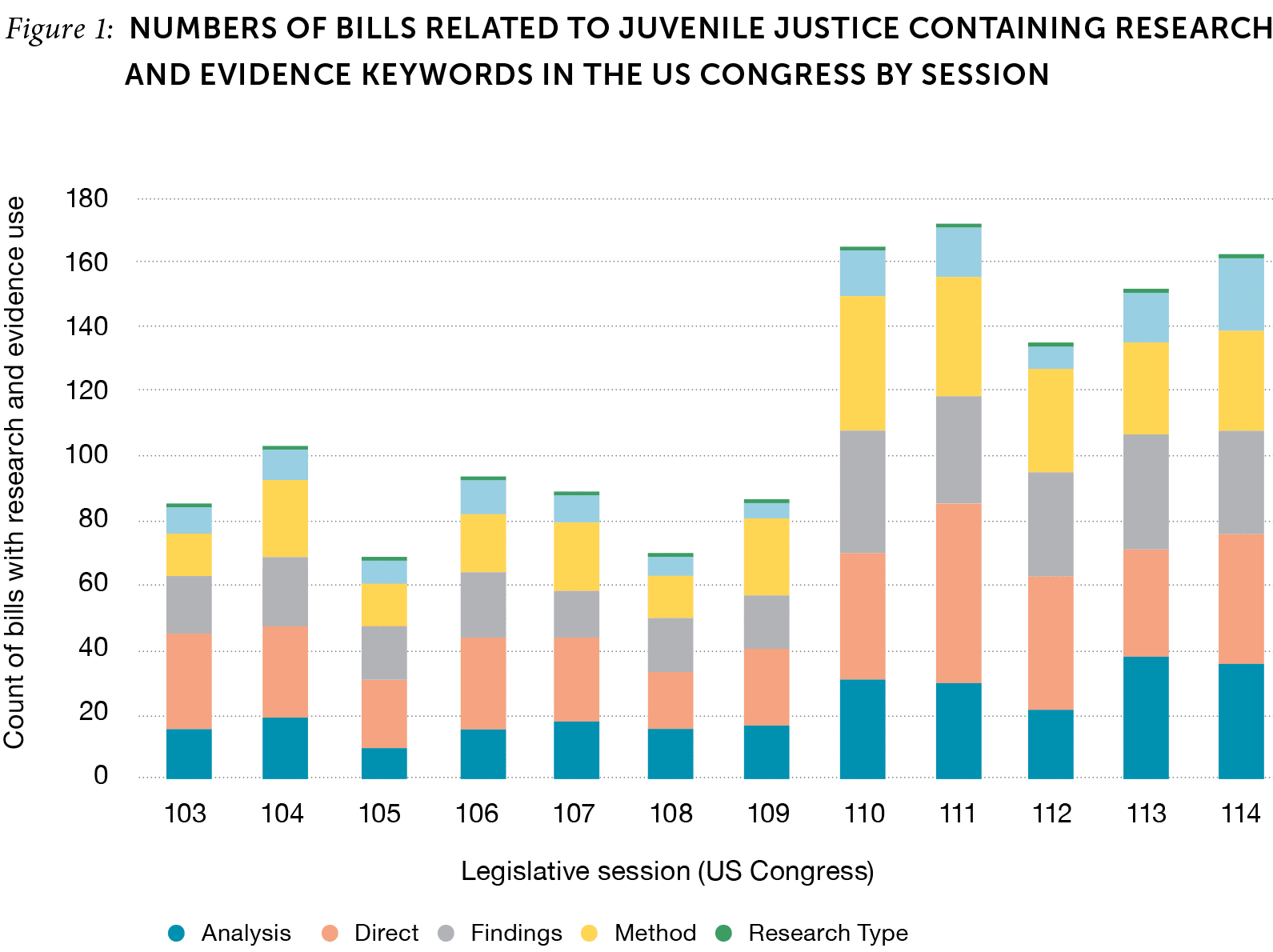

In the state and federal policy spheres, referencing research and evidence has become more common over time (Figure 1), although the proportion of total bills using evidence language has increased only slightly, from 59% to 70% between 1993 and 2017. This small change reflects missed opportunities to bring more evidence into policymaking. It is all the more surprising because studies show that bills using such terms are more likely to be successful. For instance, a review of federal behavioral health legislation over the last 30 years found that bills that explicitly referenced scientific evidence were over three times more likely to be enacted into law than bills that did not. We found similar results in other federal policy areas, such as substance abuse and human trafficking, and we replicated and expanded on this finding in studies of state-level legislation as well.

Analysis: referring to statistical processes or interpretations

Direct: referring to processes of dissemination and related terms such as “evidence-based” or “best practice”

Findings: referring to scientific literature or study results

Method: referring to the process of obtaining, collecting, or managing data or conducting studies

Research Type: referring to different kinds of studies or research without necessarily referencing findings

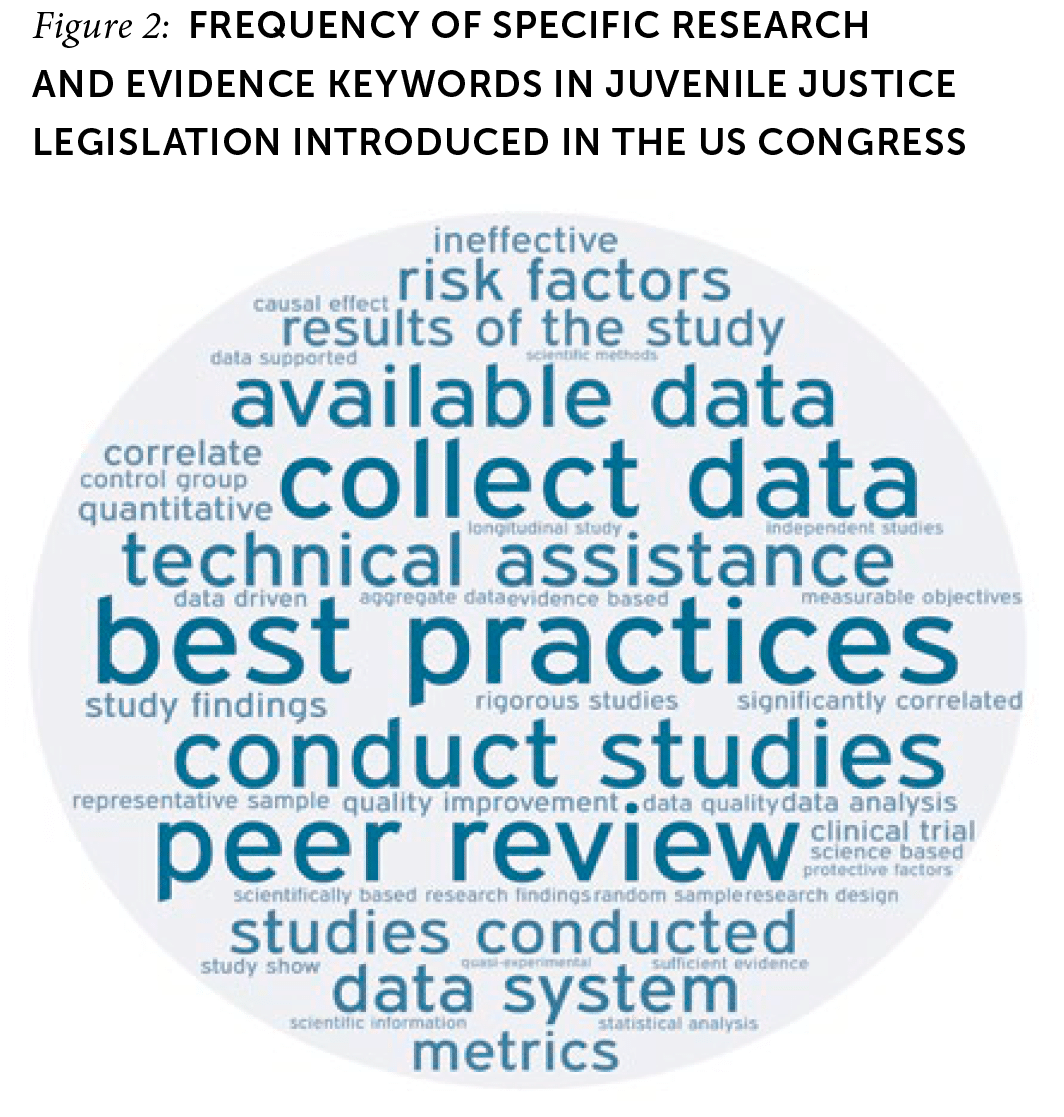

But it goes beyond the mere presence of evidence or research terms in legislative text—our findings show that the quality of these terms matters. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the frequency with which different research terms are used in juvenile justice legislation varies, but bills that directly reference scientific study designs (research type: e.g., “randomized trial” or “longitudinal study”) were 65% more likely to pass out of committee. Bills that directly reference the process of conducting studies (method: e.g., “data collection” or “data mining”) were also more likely to be enacted into law.

Bringing together all these findings, we recognized the need to facilitate diverse scientific engagement with policymakers that would systematically improve not just the quantity, but also the quality of evidence used in legislation. This is not a new challenge. A long history of efforts to increase the use of science in policymaking has highlighted the limitations of expecting policymakers to go out and find the relevant science, and even the limitations of more recent models that simply push science onto the policy community. Research shows that success requires strategies that cultivate trusting relationships directly between scientists and policymakers who desire quality information. Federally focused programs such as Science & Technology Policy Fellowships from the American Association for the Advancement of Science and state-focused programs such as the Missouri Science & Technology (MOST) Policy Initiative utilize these strategies, but they require immersive and embedded full-time fellowships for a handful of scientists per year. For the typical scientist facing existing institutional constraints, such engagement remains difficult.

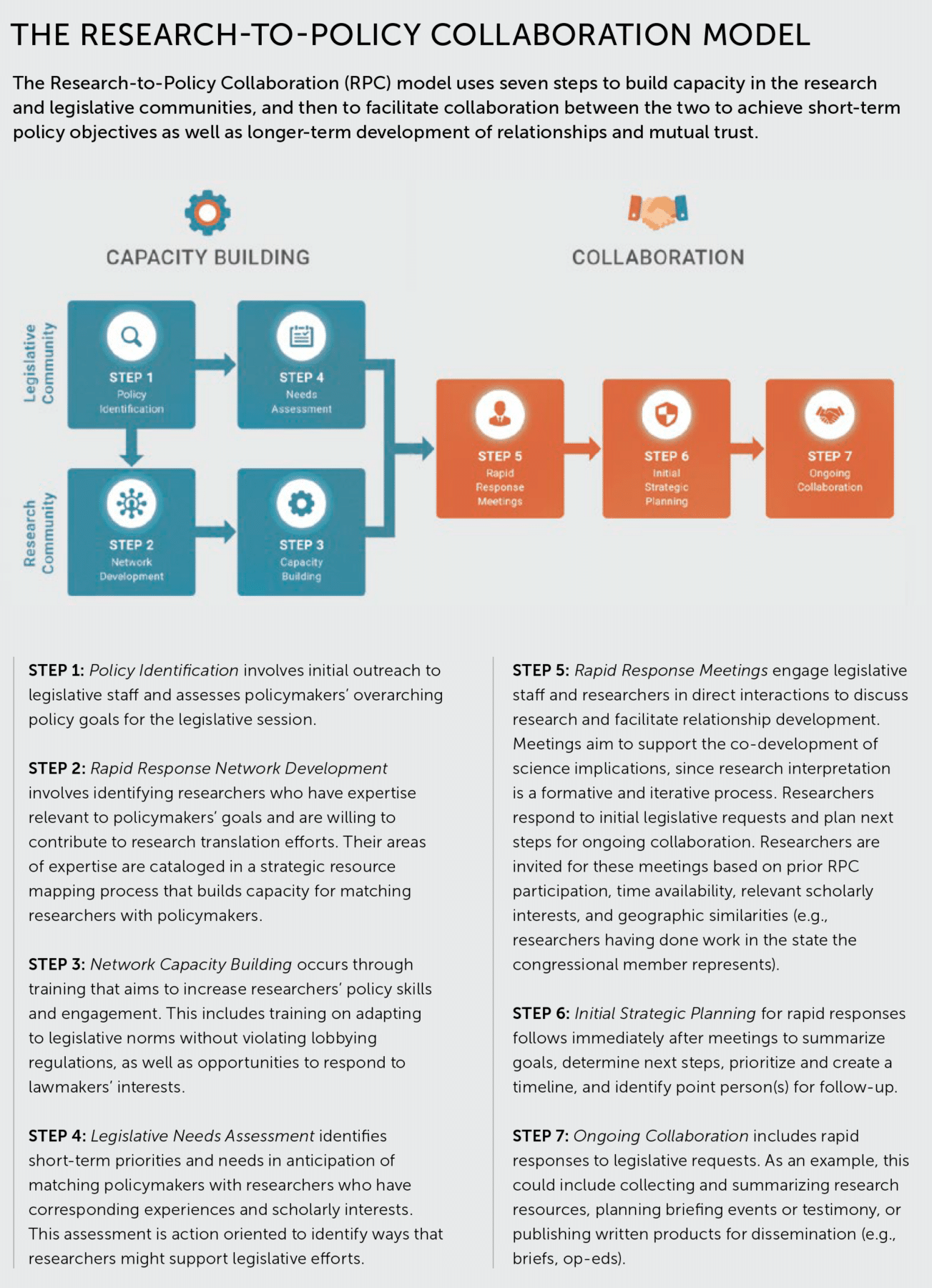

Recognizing this gap, we developed a replicable model to facilitate engagement between policymakers and the scientific community: the Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) model. The RPC is a behavioral and structural intervention that involves both policy and research communities through seven steps.

A pilot study of the RPC model with a focus on prevention science (the study of practices that mitigate and reduce the occurrence of social problems) demonstrated promising results in improving scientists’ legislative engagement, fostering legislator-researcher connections, and eliciting requests for evidence from legislative offices. This work emphasized a dual-community strategy that increased researchers’ capacity for engagement while conducting strategic assessments of policymakers’ need for scientific evidence.

Although promising, the pilot did not provide sufficient evidence that RPC actually improved use of research and methods in the legislative process. This led us to conduct a follow-up study that we believe was the first randomized controlled trial of the US Congress to improve the use of research. We randomized 96 congressional offices to either receive the support of the RPC or be assigned to a control condition where they did not. We found that though offices that participated in the RPC intervention were not more likely to introduce child and family bills, the use of research and evidence terms in bills that were introduced varied significantly between the intervention and control offices (Figure 3). Those participating in RPC were more than 20% more likely to write bills with research and evidence language compared to the control group, a statistically significant difference. They were also much less likely to introduce bills that did not include such terms. Longitudinal surveys revealed other changes in congressional offices assigned to receive the RPC—including a 7% increase in the value offices placed on using scientific evidence to understand how to think about or conceptualize problems.

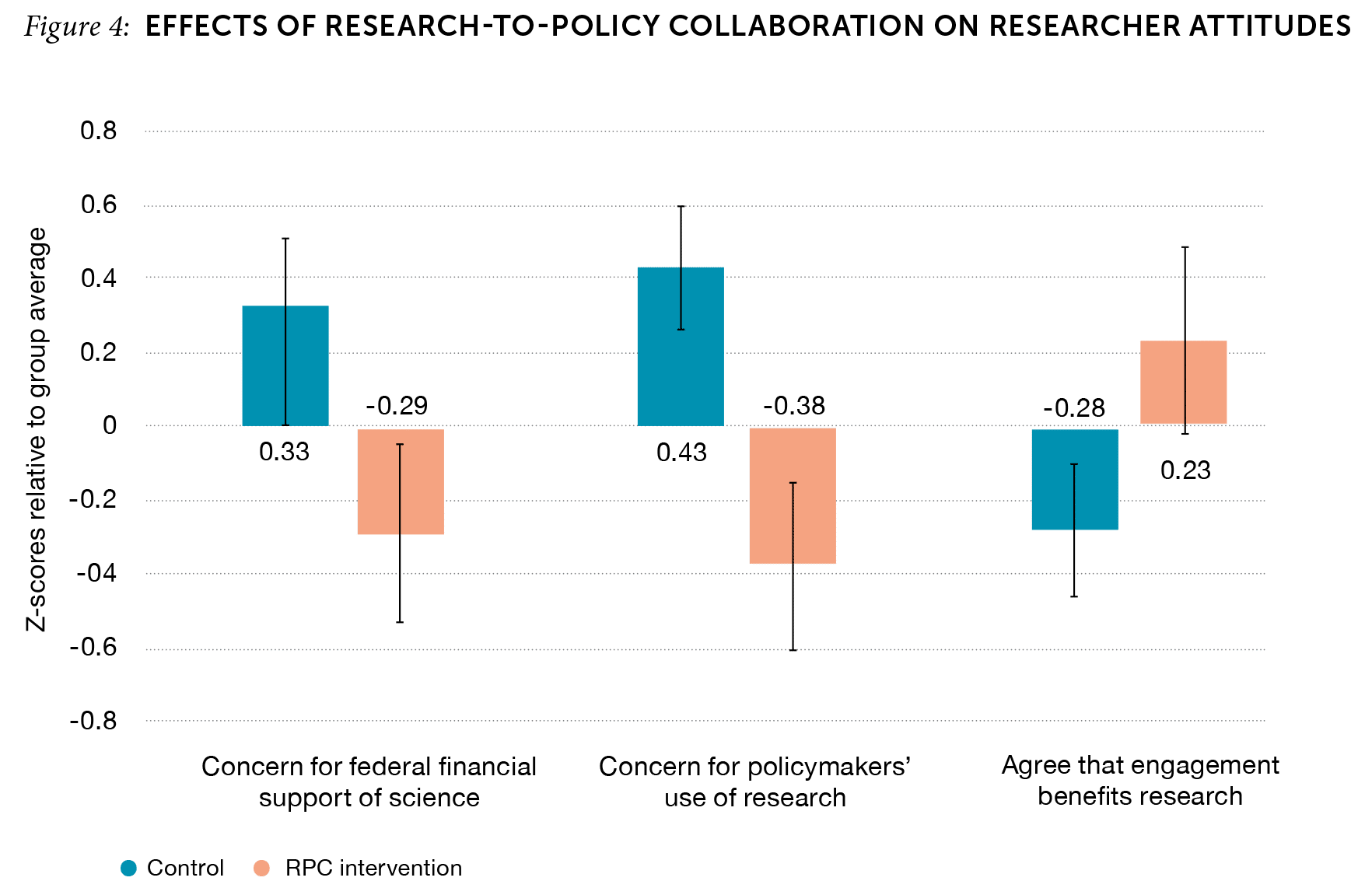

Besides its effects on legislative offices, RPC participation also had impacts on the scientific community, with benefits for researchers who participated. We conducted a parallel randomized controlled trial of over 200 researchers who either received the RPC or received traditional, static policy engagement materials instead. Compared to the control group, researchers who received the RPC were more likely to engage with policymakers, report fewer concerns about funding for science and about policymakers’ use of research and evidence, and report that their policy engagement improved their own research program (Figure 4). Moreover, researchers who identified as members of racially or ethnically marginalized groups were, before the trial, significantly less likely to engage with policy communities—but those who did engage as part of the trial reported the greatest benefits.

Although this work demonstrates the potential of experimentally validating strategies to improve the use of research, it also highlights how far both the scientific and policy communities still have to go to successfully engage at all levels of government. While designing new strategies, the scientific community must be mindful of who and how they engage, considering issues of burden—time, effort, and financial resources—on both scientists and policymakers. These strategies also need to ensure that scientists with a diverse mix of perspectives and backgrounds are included. And the scientific community must also prepare for inevitable disagreement and controversy, ensuring policymakers and scientists can effectively engage in an appropriate manner and without loss of trust when they may be at odds with each other.

Beyond strategy development, scientific and policy institutions must become more amenable to sustained, meaningful engagement around the use of evidence. Perhaps one of the greatest challenges will be culture change: finding ways to align organizational incentives that influence the behaviors of scientists, policymakers, and their staffs. Our experimental studies show that bringing scientists and policymakers together provides mutual benefits for the individuals and offices involved, as well as the larger societal benefit of improved use of evidence in policy. Looking to the future, and the many challenges that humanity is likely to face in the coming decades, such collaboration will only become more necessary if scientists and policymakers hope to best serve all members of society.