A Texas-Sized, Texas-Shaped Approach to Biomedical Research

Since 2007, Texas voters have approved $9 billion to chase cures for cancer and now dementia, embracing the idea that biomedical research is a force for public good, rather than a special interest handout to well-connected universities.

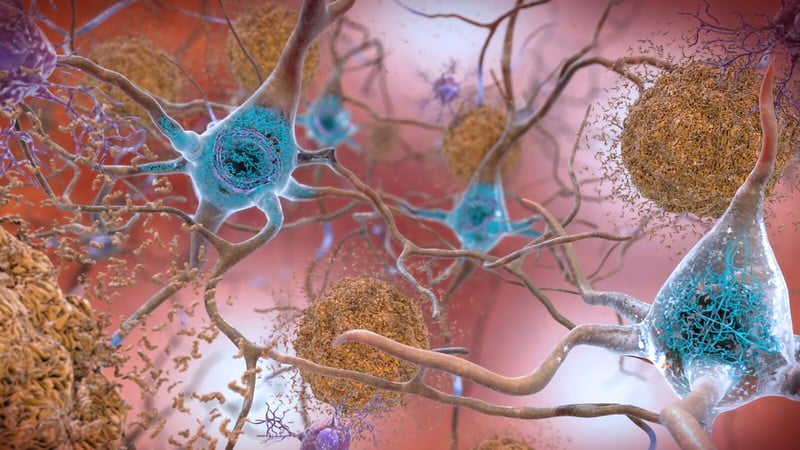

On November 4, 2025, Texas voters supported a ballot measure to commit $3 billion of public funds to dementia research over the next decade. Today, around 460,000 Texans live with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia—that’s 1 in 6 Texans aged 45 and older. These staggering numbers speak to Texas’s aging population and the prevalence of underlying health conditions, including high rates of diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity. Dementia leaves no Texan untouched: More than a million people serve as unpaid caregivers for family members, leading to tens of billions of dollars in economic costs and a rising toll on the medical and physical health of individuals and their communities.

The Dementia Prevention Research Institute of Texas (DPRIT) builds on a previous effort to fund biomedical research in the state. The Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) launched in 2007 with $3 billion dollars and renewed in 2019 with another $3 billion. CPRIT’s model has proved to be a highly successful initiative for state-level research funding. The dementia initiative follows the same structure, right down to the name, and will distribute up to $300 million annually for 10 years, placing it behind only the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as one of the world’s largest funders of research on dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and related brain disorders.

For outside observers, learning that Texas champions a progressive funding regime for biomedical research may come as a surprise. Texas, the second largest and second-most populous state in the nation, has “limited government” written into its DNA. Despite its size, its legislature only meets for approximately five months every two years to avoid employing career politicians. Over the past decade, it has used these brief periods to serve as the nation’s testbed for legislation aimed at loosening vaccine requirements, aggressively restricting access to reproductive and maternal health care, and imposing a near-ban on gender-affirming care. Texas also continues to refuse Medicaid expansion; the state has the nation’s highest uninsured rate and large disparities in access to medical care, especially in rural areas and counties with majority Black and Latino residents.

In Texas, the conservative political climate coexists alongside another reality: The state is home to a vibrant and well-resourced research community distributed across an expansive system of universities, colleges, medical schools, and research hospitals, including the Texas Medical Center—the largest medical center in the world. Furthermore, the state already had a head start in dementia research. The Texas Alzheimer’s Research and Care Consortium (TARCC), a state-funded initiative founded more than two decades ago, collects and shares longitudinal datasets for scientific use, incentivizes collaborations across its 11 member institutions, and positions Texas as a national leader in understanding, treating, and preventing neurocognitive disorders. Since 2005, TARCC has awarded over $60 million in competitive awards, an average of $3 million annually. With the creation of DPRIT, which will leverage TARCC’s infrastructure and the state’s sprawling network of medical centers, this number will increase by a factor of one hundred.

In Texas, the conservative political climate coexists alongside another reality: The state is home to a vibrant and well-resourced research community distributed across an expansive system of universities, colleges, medical schools, and research hospitals.

The boldness of the initiative was broadly appealing. Its most visible champion is Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, who envisions the state becoming “the premier destination for dementia prevention and research and [for] Texans [to] have access to the best dementia care in the world, right here at home.” Patrick is not alone in his enthusiasm. Texans voted for the proposition to establish DPRIT by a margin of 68%.

In the face of shifting funding priorities for research at the federal level, the history of the Texas funding model provides several compelling policy innovations that can inform other state-led social contracts for science. In particular, the Texas experience has revealed the importance of developing structures to handle conflict of interest (COI) protections, public transparency, and the provision of incentives that encourage state institutions to collaborate rather than compete. The initiative also offers insights into the ways that such high-risk research funding can be connected to family and community needs while also leveraging regional research strengths—and how all this can build durable political support, and even enthusiasm, among policymakers and voters.

A tale of two state initiatives

Texas’s state-level investments in biomedical research were inspired, in a competitive way, by California, which started an initiative to fund stem cell research in defiance of federal policies in the early 2000s. First isolated in 1998, embryonic stem cells, which are derived from human embryos, can become any cell in the human body, offering scientists a tool of immense promise. However, their use in research and clinical applications raises both regulatory and ethical concerns. Soon after taking office, President George W. Bush permitted federal funding of research using human embryonic stem cells, but only those created before the date of his announcement in August 2001. Researchers and institutions across the country felt that stem cells had enormous potential but faced limited funding opportunities from NIH.

In 2004, California responded by investing $3 billion over 10 years into the creation of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), with a focus on stem cells and regenerative medicine. California’s state legislature designed CIRM to fund researchers and institutions in the state with significant potential for long-term economic impacts for the state—and to sponsor science NIH could not or would not support.

Prior to its passage through Proposition 71 on the 2004 California ballot measure, advocates ran an estimated $25 million public media campaign centered around what bioethicist J. Benjamin Hurlbut described as “unrestrained hope.” To sell the initiative, the Coalition for Stem Cell Research and Cures, bankrolled by Palo Alto real estate developer Robert Klein and backed by Nobel Prize winner Paul Berg and then governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, aired emotionally charged advertisements that promised a future of cures and access to treatment. These messages underplayed the challenges of enacting policy mechanisms to deliver on such goals, let alone address the thorny ethical and moral considerations surrounding embryonic stem cell research.

In the face of shifting funding priorities for research at the federal level, the history of the Texas funding model provides several compelling policy innovations that can inform other state-led social contracts for science.

CIRM faced immediate legal challenges and near continuous public criticism, setting back the first round of awards by nearly three years. Even after the California Supreme Court refused to hear the major legal cases against it, CIRM’s early years were mired in COI controversies and accountability scandals. However, due to its governing structure and the provisions of the original ballot measure that effectively shield it from public oversight, CIRM has had little impetus to make structural changes. Its renewal, enacted through a 2020 ballot initiative, barely passed with just 51% of the popular vote; more than 8 million Californians voted against it.

Never shying away from an opportunity to compete with its rival state, Texas created CPRIT shortly after CIRM’s launch. Governor Rick Perry made cancer research a centerpiece of his 2007 State of the State address. Texas followed California’s blueprint for generating public support for the initiative, advertising the promise of cures and better lives for Texans and their loved ones. However, the Texan campaign benefited from a number of political advantages. Unlike stem cells, nothing about curing cancer is controversial. Cancer research also includes a much wider range of diseases, potential treatments, and prevention strategies than stem cell therapies, which have a narrow set of clinical applications.

The CPRIT campaign was also bipartisan. Friends of former Texas governor Anne Richards, a Democrat who died in 2006 from esophageal cancer, promoted the initiative in her honor. And there was preexisting infrastructure within the state focused on cancer research, including the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, one of the nation’s top-ranked cancer hospitals.

Texas followed California’s blueprint for generating public support for the initiative, advertising the promise of cures and better lives for Texans and their loved ones.

Governor Perry also found the perfect campaign partner in cyclist Lance Armstrong. A native Texan and America’s most famous cancer survivor prior to his admission of doping during his Tour de France victories, Armstrong traveled across Texas in Survivor One, a red, white, and blue tour bus wrapped in a giant picture of his face and the slogan “Texans Curing Cancer.” The campaign, backed by the Livestrong Foundation and MD Anderson Cancer Center, proved to be a huge success. After passing the Texas House and Senate, voters approved $3 billion in general-obligation funds and the launch of CPRIT by a 61% margin on the November 2007 Texas ballot. When Governor Perry signed the bill into law and declared the initiative would build a world where “we talk about cancer the same way we talk about polio,” Armstrong stood behind him at the podium.

Building trust with Texans

In 2009, CPRIT opened its doors under the leadership of William “Bill” Gimson, recruited from his post as chief operating officer at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Nobel laureate biochemist Alfred G. Gilman, CPRIT’s first chief scientific officer, who came from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Centers. CPRIT’s broad mandate, as written in the newly amended Texas constitution, was to support “research into the causes of and cures for all forms of cancer in humans.”

Learning from California’s experience, CPRIT worked to build public accountability through explicit COI protections and an oversight committee that included Texas’s attorney general and the state comptroller. Nevertheless, funding got off to a rocky start. During its third year of operations in 2012, two historically large CPRIT awards triggered public investigations. A report from the Texas State Auditor’s Office (SAO) found that CPRIT awarded $56 million in taxpayer money through processes that violated state law or CPRIT’s own rules, leading to a moratorium on new CPRIT grants and an overhaul of the agency’s leadership and governance. Gilman, Nobel laureate geneticist Phillip Sharp, who led CPRIT’s Scientific Review Council, and dozens of external peer reviewers resigned in protest. Gilman and Sharp coauthored an op-ed in the Houston Chronicle publicly explaining their problems on the grant review process, discussing their rationale for resigning, and sharing their perspectives on how to restore integrity to CPRIT’s grantmaking process. Public trust needed to be rebuilt.

The 83rd Texas Legislature convened shortly after at the start of 2013. Lawmakers made it clear that CPRIT’s survival hinged on serious reform. Emergency legislation, Senate Bill 149, passed in June 2013, implemented every recommendation of the SAO to tighten ethical rules of CPRIT grantmaking: It required strict COI disclosures, made external peer review the primary factor in award decisionmaking, and restructured the institute’s governance to strengthen oversight—which included the appointment of a chief compliance officer with the power to veto any award that did not meet CPRIT’s new standards. Interestingly, the new law also removed the Texas attorney general and state comptroller from the oversight committee, as recommended by the SAO. This change effectively depoliticized CPRIT oversight, leaving the attorney general and state comptroller to externally audit and investigate committee activities without having to participate on the committee. Finally, CPRIT hired new leadership, including a new chief executive officer, scientific officer, and compliance officer.

In parallel, CPRIT shifted public messaging from the politics of hope to promoting the economic returns of state investment. An annual CPRIT-sponsored study has routinely found that every dollar spent by the agency generated over $100 in economic activity for the state through new jobs, infrastructure projects, the benefits of “crowding in” (when government spending results in increased private investment), and avoided mortality through preventative screenings. The narrative shift from cures to social returns helped recreate CPRIT’s image as a force for public good, rather than a special interest handout to well-connected universities.

CPRIT’s broad mandate, as written in the newly amended Texas constitution, was to support “research into the causes of and cures for all forms of cancer in humans.”

Rather than focusing solely on biomedical research and development, as California’s CIRM program does, CPRIT was designed to support a broader portfolio of research, prevention, and talent recruitment. As of 2024, the largest share of competitive CPRIT awards went to research, with approximately $1.1 billion for clinical research, $757 million in translational research, $397 million in basic research, and $90 million for research training. The state, through CPRIT’s founding legislation, requires that up to 10% of agency funds be set aside for prevention work, which totaled $381 million in project awards since CPRIT’s founding. Preventative research funded by CPRIT includes optimizing cancer screening, anticancer vaccines (against hepatitis B and human papilloma viruses), healthy-living programs (tobacco, alcohol, and obesity), and care for cancer survivors in the Texas population. Active projects reach all 254 counties in the state, although they are concentrated in the urban centers.

Additionally, the success of the initiative is often linked to the $961 million used to recruit nearly 350 talented scientists to Texas through its CPRIT Scholars program. After moving to Texas as a CPRIT Scholar in 2012, James P. Allison, famed cancer immunologist and one of the agency’s most notable recruits, shared the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation. Other high-profile researchers came for a short period, spent the CPRIT money, then retired or left the state. As a result, CPRIT capped recruitment awards to $6 million and began prioritizing early- and mid-career recruitment awards.

In November 2019, Texans renewed CPRIT for a second $3 billion in state funding over ten years with 64% of the vote. The program survived its early missteps in governance to establish itself as a robust funding mechanism worthy of continued public support. As of 2025, CPRIT has funded over 2,200 competitive awards across the state, led more than 300 clinical trials, and treated more than 57,000 cancer patients. In Texas, almost all new medical advancements in cancer therapeutics are linked to CPRIT through its funding of foundational biotechnology, clinical trials, or infrastructure. By this measure, the initiative has been a resounding success, realizing Governor Perry and Lance Armstrong’s original vision: If you want to cure cancer, come to Texas.

Texas builds on cancer to tackle dementia

DPRIT’s origin story has, to date, been far less eventful than its predecessors. Following CPRIT’s playbook, the initiative was championed by state Republican leadership, Lieutenant Governor Patrick, and the advocacy organization of another American icon: the actor Michael J. Fox. Texas Senate Bill 5, and later, November 2025’s Proposition 14, experienced little to no pushback from the public nor from lawmakers, despite its steep price tag and the state’s usual reluctance to spend its surplus tax revenue on public infrastructure or social services. After sailing through the legislature and the popular vote, it did, however, hit one snag: Three plaintiffs filed a lawsuit after the election arguing voting machines had not been properly certified—a common strategy used by advocates for limited government in Texas—that will likely slow down the process of launching DPRIT and its first round of awards toward the end of 2026.

In structure, DPRIT is almost identical to the current CPRIT model, including annual funding levels and its mechanisms for governance and public oversight. However, there is a key difference in how funding is appropriated. Although the Texas legislature funds CPRIT through biennial state-issued bonds, DPRIT received a direct appropriation of $3 billion that was set aside in total to be used over 10 years. Still, since both were passed through amendments to the state constitution that required voter approvals, the funds are all but guaranteed and functionally equivalent, barring an unlikely constitutional amendment in the future.

In Texas, almost all new medical advancements in cancer therapeutics are linked to CPRIT through its funding of foundational biotechnology, clinical trials, or infrastructure.

As researchers across Texas prepare to compete for DPRIT funds, several important questions remain. The biggest unknown is who will be selected to lead the institute. Leadership proved to be crucial to rebuilding CPRIT’s public trust and ensuring long-term viability. This is particularly important because although DPRIT is following the processes pioneered by CPRIT, new leadership will need to determine how the funding is allocated among basic, translational, and clinical research, and recruitment. Leadership will also need to tackle a second major question around how the institute defines its scope. The legislation did not define dementia beyond stating that DPRIT would focus on “dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and related disorders.” It remains to be determined what research will be eligible or prioritized under the broad umbrella of “related disorders.”

Some scope of dementia prevention projects are assumed to be funded, given CPRIT’s precedent. However, DPRIT’s statute places a cap on how much: “Not more than 10 percent of the total amount of grant money awarded under this chapter in a state fiscal year may be used during that year for prevention projects and strategies to mitigate the incidence of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or related disorders.” This clause limits the scale of preventative research the agency can support, and the language permits the agency to skip funding prevention altogether, despite it being part of the institute’s name. Other spending caps in the law include a 5% cap on facilities and a 5% cap on indirect costs, leaving institutions to cover the substantial overhead costs associated with medical research.

A Texas-sized, Texas-shaped model for medical research

DPRIT, and CPRIT before it, are Texas-sized and Texas-shaped approaches to biomedical research funding. The state has leveraged its massive tax base, existing state infrastructure, and flagship medical and research institutions to craft a bipartisan model for high-risk medical research. In total, the agencies provide record-setting state funding for biomedical research: $600 million per year in total. Texas lawmakers then effectively designed and implemented a politically expedient and clearly biomedicalized policy strategy for addressing cancer and dementia, two leading causes of mortality within the state. Consequently, both initiatives are narrowly focused on research rather than confronting broader policy challenges for health care delivery or public assistance in the state.

The state has leveraged its massive tax base, existing state infrastructure, and flagship medical and research institutions to craft a bipartisan model for high-risk medical research.

Medical innovation alone will not solve all the challenges facing Texans living with cancer or dementia. The Texas government’s continued refusal to expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, leaving 17% of the population without medical insurance, demonstrates its lagging and selective approach to tackling nonmedical factors that impact these diseases. Neither DPRIT nor CPRIT addresses how to ensure discoveries—funded by Texas taxpayers—will be accessible and affordable to the majority of Texas residents. Further, Texas policies and rhetoric surrounding vaccines, reproductive health, and gender-affirming care could affect DPRIT and CPRIT recruitment of star researchers to the state.

The overwhelming voter approval of CPRIT and DPRIT signals a willingness among Texans to depart from the state’s longstanding commitment to limited government in favor of targeted public investments in biomedical research. Addressing the social, environmental, geographic, and other nonmedical root causes of these increasingly common diseases will be far more complex and politically divisive. For the Texas model to serve communities across the state, beyond delivering short-term economic returns, lawmakers will need to apply the same long-term vision and investment to social policy and public health services as they have toward biomedical innovation.