OECD Science, Technology, and Industry Outlook

Despite the economic slowdown that spread across the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) area in 2001, investment in and exploitation of knowledge remain key drivers of innovation economic performance, and social well-being. Over the past decade, investments in knowledge–as measured by expenditures on research and development (R&D), higher education, and software–grew more rapidly than did gross fixed capital formation and played an important role in driving economic growth.

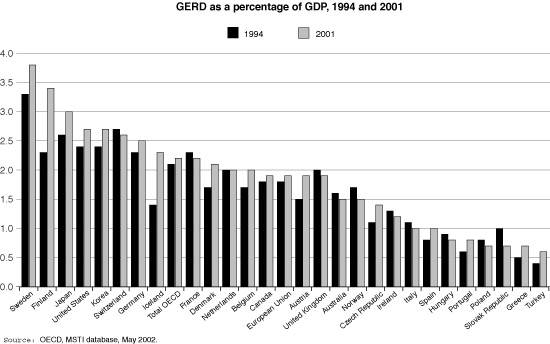

After stagnating in the first part of the 1990s, OECD-wide R&D investment grew in real terms from US$ 416 billion to US$ 552 billion between 1994 and 2000, and R&D intensity climbed from 2.04 percent to 2.24 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The European Union (EU) as a whole lagged behind the United States and Japan in R&D intensity, prompting calls to boost the EU’s R&D intensity to 3 percent of GDP by 2010.

OECD governments are paying more attention to the contribution of science and innovation to economic growth and have introduced a variety of new initiatives and reforms to better harness the results of their investments in S&T.. Linkages between industry and science and diffusion of knowledge within national innovation systems are emerging as a primary focus for innovation policy. Industry not only increased its in-house R&D spending but is also increasing its support for university research. Public research is being reformed to contribute to economic and social needs.

Growth in research is increasing the demand for skilled workers and researchers, which is leading to changes in immigration and education policy, as well as to the creation of centers of excellence to act as magnets for scientific and technical talent. Many countries are making it easier for highly skilled workers to enter permanently or temporarily, and they are also increasing support of higher education to increase the supply of homegrown talent. Countries such as Chinese Taipei, Ireland, and Korea, which have seen a large number of their best workers leave, are experiencing success with policies to lure some of these workers back, especially as their domestic science and technology capabilities have improved.

The source of this information plus a great deal more data and an analysis of the policy environment is the OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2002, which is available at www.SourceOECD.org.

R&D expenditures continue to grow

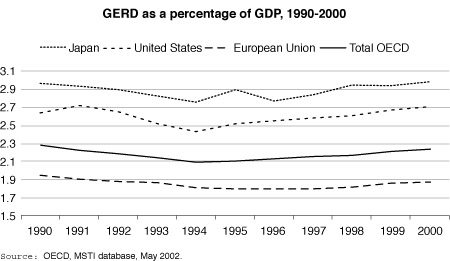

After a decline in the early 1990s, Gross expenditures on R&D (GERD) rose steadily across the OECD area and appeared to be on a continuing upward trend through 2001, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP. Cutbacks in business R&D in high-tech sectors will likely stunt growth in 2002, but R&D intensity in the United States and Japan has surpassed 1990 levels. R&D intensity in the EU has yet to recover fully to the 1990 level.

Research intensity varies across the OECD

Countries that posted the highest percentage gains in R&D intensity tended to be those with already high levels of R&D and with growing information and communication technologies and service sectors, such as Finland and Sweden, further widening the gap between them and less R&D-intensive countries , such as Poland, Hungary, and the Slovak Republic. Several large European countries, including France, Italy and the United Kingdom, saw R&D levels fall as a share of GDP during the 1990s.

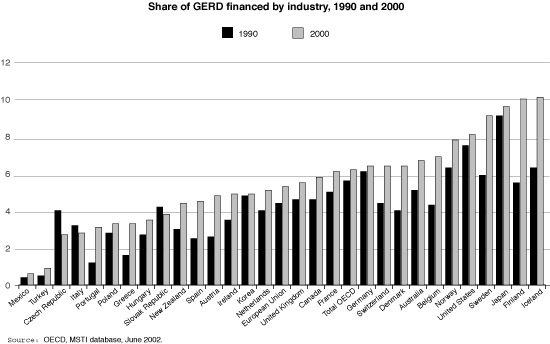

Industry responsible for most R&D growth

Growth in R&D expenditures during the 1990s resulted almost exclusively from increases in industry-financed R&D, which grew by more than 50 percent in real terms between 1990 and 2000, driven largely by high-tech industry. Government-funded R&D grew by only 8.3 percent during this period. As a result, the share of total R&D financed by industry grew from 57.5 percent in 1990 to 63.9 percent in 2000, whereas the government’s share fell from 39.6 percent to 28.9 percent.

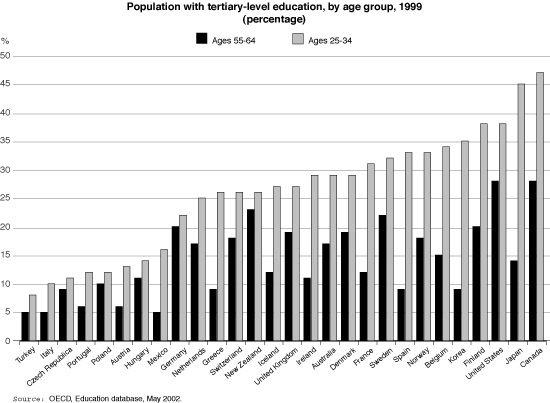

Closing gap in higher education

Although spending on higher education did not rise very quickly in the 1990s, the long-term trend throughout the OECD is for a higher percentage of people to continue their education beyond secondary school. Comparing the percentage of people of different generations who have completed tertiary education makes it clear that all countries are making progress and that those countries that have historically had the lowest levels are beginning to close the gap with the world leaders, increasing their ability to compete in a knowledge-based economy.

Human resources are critical

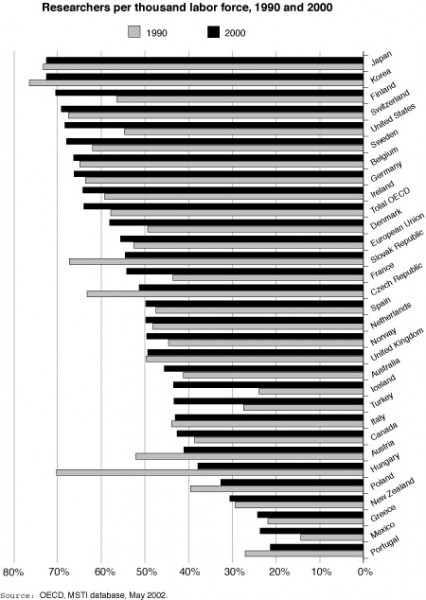

The stock of researchers expanded in almost all OECD countries in the 1990s, with total researchers per thousand in the labor force reaching 6.2 in 2000 compared to 5.6 in 1990. The EU lags behind the United States and Japan in total researchers and the share in the business sector. Future growth in Europe and Japan may be slowed by the aging of the research workforce and a declining share of enrollment in science and engineering fields.