The Real Returns on NIH’s Intramural Research

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research. The agency supported a budget of over $47 billion in fiscal year 2024, awarding nearly $32.5 billion in research grants to more than 12,000 investigators. By one estimate, this extramural research—conducted outside the agency—generated nearly $95 billion in economic activity across the United States and paid the salaries for an estimated 400,000 jobs. A 2018 study found that the published results of NIH-funded research projects were linked to every new drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration between 2010 and 2016.

Less studied are the social and economic outcomes from NIH’s intramural research program (IRP). NIH spent about $5 billion in FY 2024 to support the salaries of roughly 1,200 principal investigators and 4,000 postdoctoral fellows conducting research in the laboratories attached to most of the NIH’s institutes and at the NIH Clinical Center, a 240-bed research hospital. IRP scientists conduct long-term research projects, monitored through rigorous reviews, on topics that also help advance NIH’s mission to generate knowledge to help people live longer, healthier lives and to reduce illness and resulting disabilities.

Using special access to NIH’s licensing records under an agreement with the NIH Office of Technology Transfer, we led a team at the nonprofit research institute RTI International that conducted a series of retrospective analyses on the thousands of licensing agreements negotiated by NIH from 1980 through 2021. By matching internal technology transfer records to external data (such as US patents, corporate financial documents, and public health data), we generated a series of indicators that characterize the scale and scope of the impact of technologies developed by the intramural researchers at NIH.

Our results show that NIH’s intramural research generates benefits far beyond the property lines of its facilities and laboratories. Through its licensing and technology transfer activities, intramural research generates enormous economic benefit. But even more significant—and less immediately obvious—is the critical role it plays in enabling biomedical innovation at entrepreneurial and established firms. Inventions at NIH form the basis of completely new therapeutics and devices, and they also provide key research capabilities used to develop new drugs and interventions, as well as technologies to accelerate research translation.

The public benefits of NIH technology transfer

IRP scientists’ discoveries lead to new inventions that affect both patient and population health. Some of the most well-known products developed from IRP research are the first HIV test kits, the PreserVision vitamin supplement to slow macular degeneration, and Gardasil, the vaccine to combat the human papilloma virus (HPV).

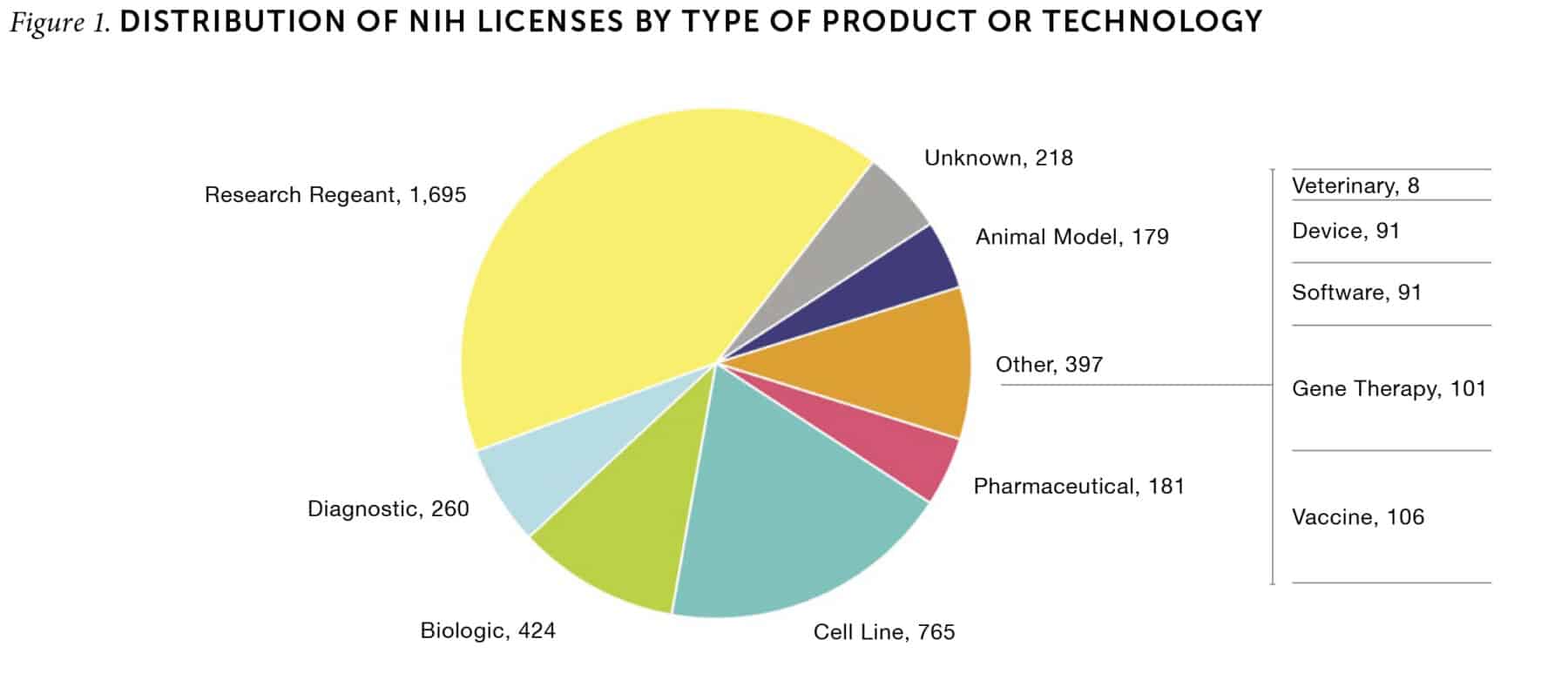

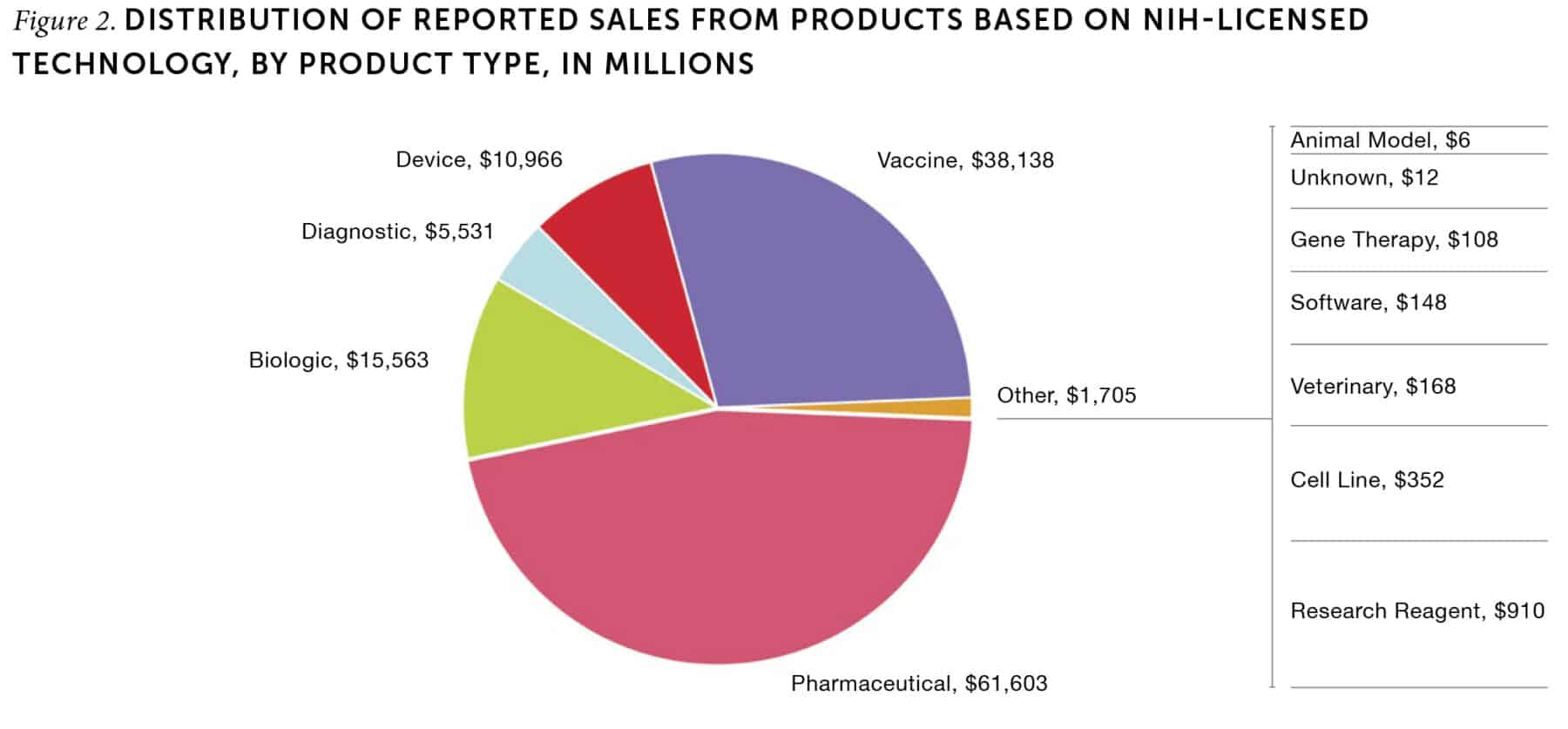

By law, inventions originating with IRP research belong to the federal government, and the Department of Health and Human Services can choose to file for patent protection to claim that intellectual property. Since NIH does not produce commercial drugs or services, the agency’s technology transfer offices offer these inventions for licensing by firms and other organizations under a legal framework established in 1980 by the Stevenson-Wydler Technology Innovation Act. Between 1980 and 2021, NIH issued over 4,000 licenses for technologies applicable to a range of biomedical products, including pharmaceuticals, biologics, and vaccines (Figure 1). Not all inventions ended up in commercially successful products, but sales reports from the licensees indicate that these technologies contributed to products generating more than $133 billion in US market sales during that period. Since licensees only pay royalties until the patent expiration date—and many products remain on the market beyond then—this is an underestimation of the actual sales figures.

A firm licensing one of NIH’s inventions receives very specific rights to use that technology in its own research and development efforts. In return, the firm pays a royalty fee back to NIH, which can be a fixed fee (tied to completing milestones in its plan), a share of the gross sales of any products based on the technology that is introduced to the market, or both. The law requires that a small share of any received royalty payments be distributed to the NIH scientist(s) who invented the technology, and the remainder is reinvested in additional NIH research. The patents on inventions by IRP scientists remain the property of NIH. Overall, NIH received nearly $1.8 billion in royalty payments between 1980 and 2021.

However, it would be misleading to take those royalty payments as the sole measure of the value of the benefits generated by IRP discoveries. The sales of the commercial products that incorporate those discoveries produce much greater economic benefits. We estimate that US sales from 2001 through 2021 supported an average of 36,600 full-time equivalent positions per year in the firms that brought those products to market, which translates to an average of $1.7 billion in household income per year. After including the products and services sold to those firms and their employees by suppliers and other companies, these sales spurred economic activity that provided over $4.2 billion in US household income in an average year.

Since the mission of NIH is to improve human health and prevent or mitigate the effects of diseases and conditions, the ultimate value of IRP discoveries should be measured in how they help to extend the lives of patients. Quantifying the health-related impacts of many of these inventions can be challenging, as the results add up far downstream from the original innovation—but the accumulated benefits are significant. For example, our study estimates that use of Gardasil and other HPV vaccines prevented over 80,000 individuals in the United States from developing cervical cancer from 2008 to 2019. At prevailing mortality rates for cervical cancer, the HPV vaccine can be credited with preventing more than 28,500 US fatalities from cervical cancer over that period.

The scaffolding that supports biomedical and biotechnology research

NIH’s intramural research generates less visible but critical benefits to the entire US biomedical innovation system. The products that help to prevent, treat, or cure diseases generate the bulk of commercial sales related to licensed IRP inventions—approximately 86% of total sales from 2001 through 2021 (Figure 2). In contrast, the inventions that are licensed most frequently are research tools and materials such as reagents, cell lines, and animal models. Biomedical researchers use these resources to conduct preclinical research as part of the drug development process. These tools are essential to conducting both in vitro and in vivo (outside of or within a living organism, respectively) testing of potential drug targets. Notably, cell lines have become a standard tool in biomedical research labs to test how a living cell might react to an intervention without the need to use a living cell. The Murine Colon 38 cell line alone has been licensed over 170 times, more than any other NIH invention. The top four cell lines together have been licensed 383 times. Similarly, research reagents—chemical compounds used in laboratory experiments—constituted over 40% of all patent licenses issued by NIH.

Many of the tools invented by IRP scientists are offered for free to academic researchers, but firms generally pay a nominal, flat-rate royalty for their use over a set period. Although they are among the inventions licensed most often from NIH, cell lines, reagents, and animal models constituted only 7% of the royalties paid to NIH from 1980 through 2021. By making these resources available for all biomedical scientists, IRP enables more efficient and effective testing within the regulatory requirements, thereby ensuring that only the most promising therapies advance to clinical trials. In most cases, these research tools would not be available to researchers but for the work of the IRP, which is motivated by NIH’s commitment to public benefit, not profit.

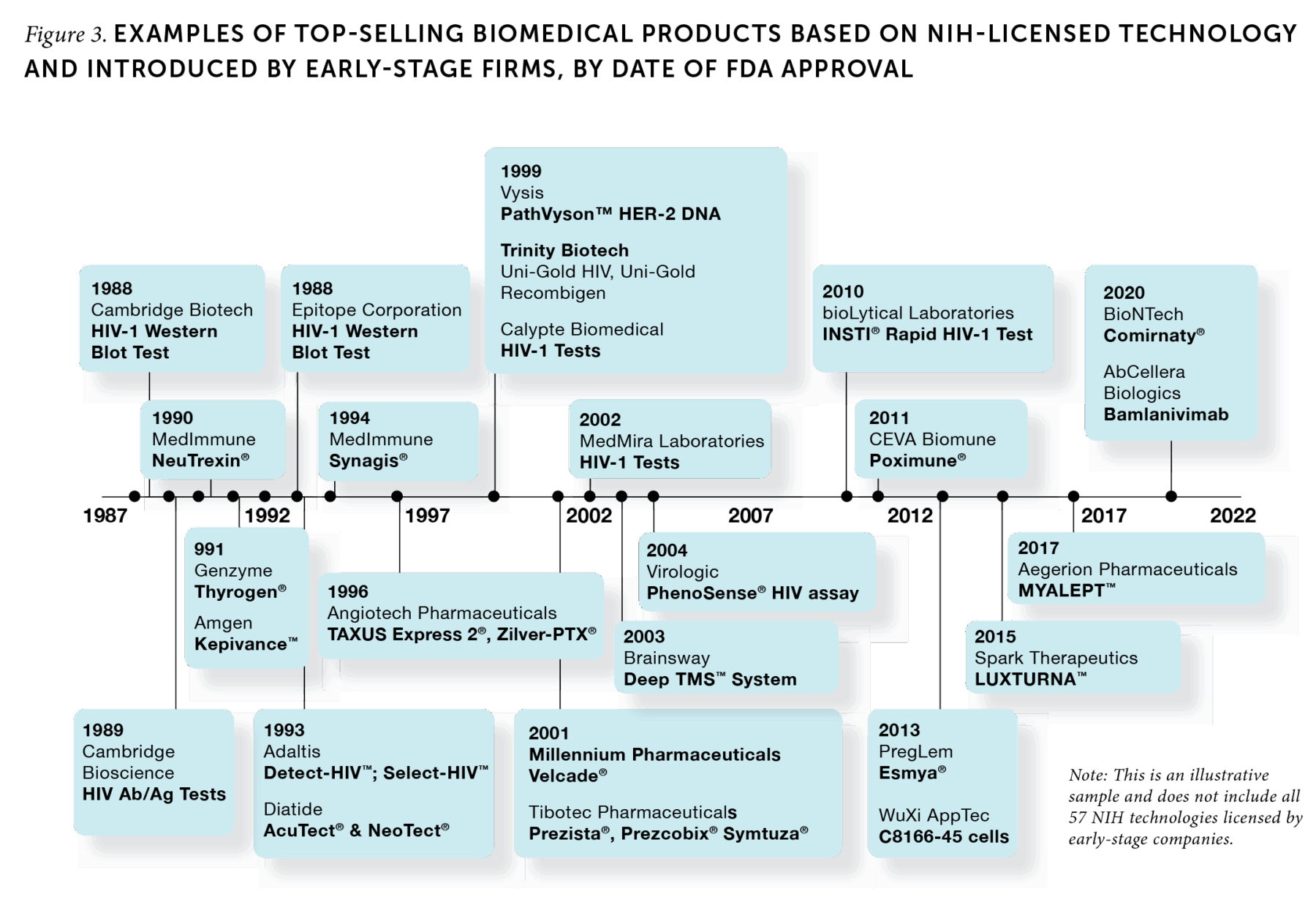

IRP funding is also an integral support for biomedical entrepreneurship. By law, NIH must give early-stage companies (those less than 15 years old) preferential treatment as potential licensees. Inventions produced by the IRP are at the cutting edge of biomedical science, so large and established firms are often unwilling to invest the time and funding it would take to try to bring them to market. In contrast, entrepreneurial firms are well suited to build off these technologies to create innovative products. A large share of top-selling products using NIH-licensed technologies (60 of the 150 top products) were developed by early-stage firms (Figure 3). Of the 55 early-stage firms responsible for those successful products, 41 went on to become publicly traded firms or were acquired by larger companies. By working with early-stage companies, scientists at NIH’s IRP enable the development of new therapies and other treatments that are too risky for established firms.

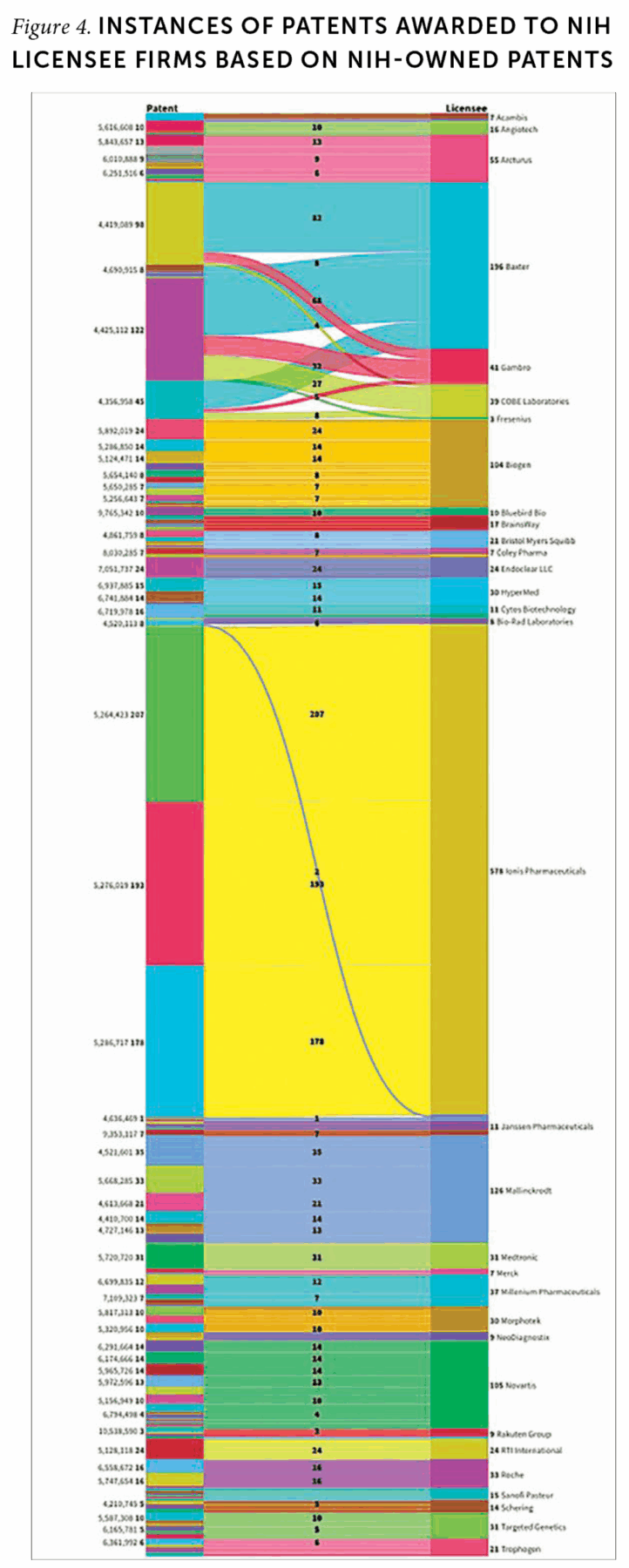

Finally, intramural research acts as an engine of development for complementary or enabling technologies. Patent analysis can provide signals of how licensees of IRP research continue to elaborate on NIH technology (Figure 4). In applying for a patent, applicants must cite prior patents related to the invention, which means patent citations track the ways new inventions build on preceding ones. One company, IONIS Pharmaceuticals, cited at least one of the three NIH patents it licensed in 578 of its own US patents. Other notable companies’ cited patents show similar evidence of follow-on invention.

Simple financial calculations estimating the return on investment from intramural research at NIH fail to capture the critical value that such research contributes to the US economy and to public health. The nation receives much greater benefits than what is captured in returns to NIH—in terms of innovative biomedical treatments, private sector activity and employment, lives extended and saved, and successful new ventures. The IRP enables a large share of academic and private biomedical innovation by providing the fundamental tools and resources needed for drug development that would otherwise be closely protected by private companies—or not exist at all. Along with supporting research at universities, research institutions, and small firms, NIH’s intramural research capabilities are an integral element in making the United States a leading nation in biomedical innovation.