Among the Very Greatest Conquests

Review of

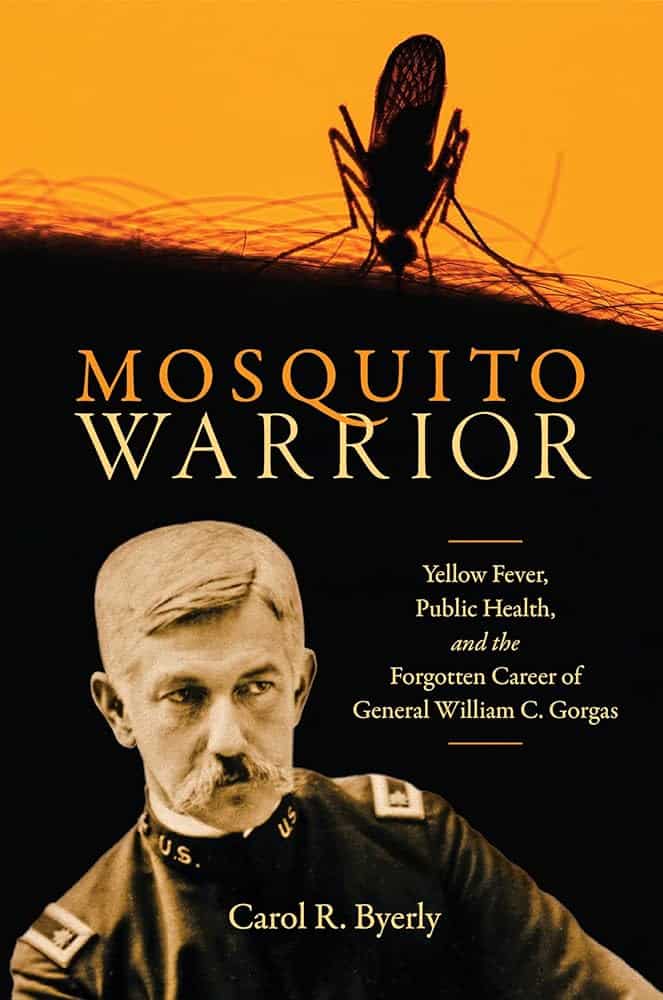

Mosquito Warrior: Yellow Fever, Public Health, and the Forgotten Career of General William C. Gorgas

Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2024, 432 pp.

The equatorial regions of the earth host the greatest number of species, whether insects, pathogens, or valuable crops such as coffee, sugarcane, and fruit. It is this conjunction of disease and valuable crops that created the demand that such regions be made habitable for human workers. Rich soils in the warm Caribbean and the southern United States, for example, made sugarcane and cotton planters wealthy. But these regions also hosted mosquitos and other vectors that made workers’ lives miserable and short. Likewise, when work on the Panama Canal was stymied by disease, its location in a tropical region at the narrowest strip of land between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans made its disease climate a geopolitical issue for the French and then American governments.

The discipline of global health focuses principally on tropical and subtropical countries for the simple reason that they continue to be home to intractable epidemic diseases. One of the giants in the history of this field,William Crawford Gorgas, is the subject of Mosquito Warrior, Carol R. Byerly’s well-written and rigorously researched biography. Gorgas, a US Army physician and surgeon general of the US Army during World War I, took some of the first steps in the long struggle to control yellow fever, a deadly viral hemorrhagic disease brought to the Western Hemisphere in the seventeenth century.

Mosquito Warrior is the first academic biography of Gorgas in half a century, and the first to make full use of the manuscript record. Byerly’s archival research in (among other places) the National Archives, the National Library of Medicine, the University of Alabama, Rockefeller Archives, and the Library of Congress must represent many hours of staring at cursive written in brown ink on yellowed, fading papers.

Born in 1854, Gorgas began his medical career at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City. There, he worked with William Welch, one of America’s foremost experts in hygiene and public health, who would go on to become the first dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. It was during this time that Gorgas was exposed to the new medical science that recognized bacteriology and the power of disinfectants.

Byerly’s archival research must represent many hours of staring at cursive written in brown ink on yellowed, fading papers.

In 1880, Gorgas passed the army medical exam and was sent to frontier army posts out West. Two years later, he was in Matamoros, Texas, when yellow fever broke out. Gorgas, ignoring orders, dissected a man who had died of yellow fever. Sure enough, he contracted the disease, but survived and became immune to yellow fever for the rest of his life. This immunity made him an asset for the US Army. In what would become a pattern throughout his career, the army then sent him to a fort near Pensacola, Florida, where yellow fever had broken out. In 1898, he was sent to Cuba to join the physician Walter Reed and others in fighting yellow fever there.

Byerly records the efforts taken by the Yellow Fever Commission, a four-person army research team based in Cuba that studied treatments for the disease. The commission confirmed Cuban epidemiologist Carlos Finlay’s hypothesis that the Aedes aegypti mosquito transmitted the virus, and subsequently experimented with keeping yellow fever patients in screened cottages to control transmission. Experts continued to suspect filth was important too, but the new theory of mosquito transmission would not go away. Walter Reed and his colleagues demonstrated that simple interventions such as window screens and insecticides could prevent the disease among the American troops stationed on the island.

Gorgas, who was the army’s chief sanitary officer in Cuba, launched the first community-wide campaign against yellow fever based on the mosquito vector. His success in effectively eliminating yellow fever cases in Havana represented the first steps in the long struggle to control this deadly disease. Although Reed has received much of the glory, it is clear from Byerly’s account that Gorgas deserves at least as much, if not more, of the credit in inaugurating the crusade against yellow fever.

Gorgas’s next task was to combat yellow fever and malaria during the construction of the Panama Canal, overseen by the US Army Corps of Engineers. The French had been chased off by yellow fever, but Gorgas was able to bring the disease under control by following the tenets of the new transmission theory. To limit mosquito exposure in the tropical country, Gorgas and his team had to deal with porous housing, poor sanitary facilities, and rainwater collected in cisterns—a popular mosquito breeding place—which were used to avoid the fecal contamination of ground water.

In the end, President Teddy Roosevelt proclaimed that defeating yellow fever would “stand as among the very greatest conquests, whether of peace or of war, which have ever been won by any peoples of mankind.” It is not too much to say that this is the apogee of the Gorgas story. Reed may have confirmed the mosquito as a vector, but Gorgas showed how hard and scrupulous work could make a tropical region healthy and safe—at least “for the white man,” as Gorgas claimed in his 1909 presidential address to the American Medical Association, titled “The Conquest of the Tropics for the White Race.”

President Teddy Roosevelt proclaimed that defeating yellow fever would “stand as among the very greatest conquests, whether of peace or of war, which have ever been won by any peoples of mankind.”

Byerly faces the ingrained racism of Gorgas head-on. She points out that his father served as an officer in the Confederate Army, and Gorgas himself was not admitted to West Point because of his Confederate connections. (Instead, he attended Sewanee: The University of the South.) In his address to the American Medical Association, Gorgas’s central point was that the tropics could be made safe for “the Caucasian” if proper mosquito control measures were applied. He predicted that over the next millennium there would arise “localities in the tropics [that] will be the centers of as powerful and as cultured a white civilization as any that will then exist in temperate zones.” Although Gorgas does not reference it, I wonder if he was thinking of Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden,” published a decade before.

In 1914, President Wilson appointed Gorgas to be surgeon general of the US Army, and he spent the First World War working to maintain the health care of a vast army at home and abroad. That he had trouble organizing such an enterprise on the fly is perhaps not all that surprising. After the war he returned to tropical medicine whenever he was able, including projects of research and treatment projects in the American South and elsewhere.

As the United States withdraws from global public health efforts around the world, now is an apt time for a detailed consideration of the long history of US government funding of tropical medicine research.

Despite Gorgas’s successes in controlling yellow fever more than a century ago, the disease is still with us. Even with multiple technologies for mosquito control (particularly insecticides and screens) and the invention of a yellow fever vaccine that grants lifelong protection after a single dose, the World Health Organization reports that during 2023 four countries in South America—Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, and Brazil—reported 41 cases of yellow fever resulting in 23 deaths. As the United States withdraws from global public health efforts around the world, now is an apt time for a detailed consideration of the long history of US government funding of tropical medicine research.

Mosquito Warrior is the story of an impressive man who was at the center of tropical medicine during a period that saw major discoveries and strides in global health. Byerly does not flinch from the negative aspects of Gorgas’s character—most notably, his persistent and public bigotry. It is a good reminder that the explosion of tropical medicine knowledge early in the twentieth century occurred in an American world that was both modern in its science and repugnant in its racism. Byerly has given us a masterful portrait of this complex, resourceful physician who served such a prominent role in American and military public health.