How to Magnify the Benefits of Federal Infrastructure Funding

A handful of changes to the way railroads, public transportation, and highways are funded could be transformational.

Recent federal proposals to modernize the nation’s infrastructure have the potential to bring significant benefits to the American people. The Biden administration’s infrastructure proposals, including the American Jobs Plan, aim to address overarching goals of racial and economic equity, sustainability, and resiliency, and to extend the traditional definition of infrastructure to include elements such as broadband access and social programs. Still, the administration is dedicating a significant portion of the overall proposed funding to surface transportation infrastructure, including railroads, public transportation, and highways. A handful of key changes in current funding policies could greatly magnify the benefits to the American public and make it truly transformational.

Railroads

The federal government’s existing approach to passenger rail funding limits the nation’s ability to upgrade its railway infrastructure. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Capital Investment Grants (CIG) program is a major funding source for commuter rail and other fixed-guideway transit (including light rail and subway) capacity and expansion projects. The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) provides funding for longer-distance passenger trains between cities, such as Amtrak). Unfortunately, this approach does not consider that the country’s busiest railway corridors—in the Northeast, California, and the Chicago area—carry both commuter and intercity trains.

The administration is dedicating a significant portion of the overall proposed funding to surface transportation infrastructure, including railroads, public transportation, and highways.

Bifurcating funding responsibility for intercity and commuter projects between FTA and FRA requires project sponsors to pursue separate funding for the same project. Allowing FTA to fund both the intercity passenger rail as well as the commuter share of project costs through the CIG program would streamline the pursuit of funding from federal agencies. It would also reflect the reality that both commuter and intercity passenger rail use the same infrastructure. Since the CIG program is already established and poised to support several critical projects in the development pipeline, it would make sense to use the existing funding system to consolidate the current silos that exist between FRA and FTA.

Among the corridors that would benefit from this approach is the Northeast Corridor (NEC), which has several critical projects on the horizon that support both commuter and intercity rail service. One of the largest programs currently underway is the Gateway Program, the phased rehabilitation and expansion of the rail connection between Newark, New Jersey, and New York City. This 10-mile rail segment accounts for more than 200,000 daily passenger trips on both Amtrak (intercity rail) and NJ Transit (commuter rail) trains. A rapidly growing regional population, as well as damage caused by Superstorm Sandy to the existing North River Tunnels in 2012, has made this program a local and regional priority. The project has become a poster child for the complexity involved in combining federal transit and rail funding—as both FRA and FTA are responsible for federal funding that flows to Amtrak and NJ Transit respectively.

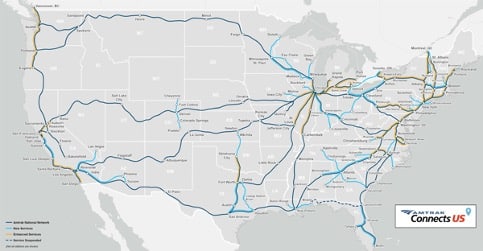

One impediment to significant investment in passenger rail projects is the lack of a dedicated multi-year federal funding stream for passenger rail in the United States. By contrast, highways and transit systems are guaranteed relatively consistent federal funding year to year through the Highway Trust Fund. Federal proposals to establish a new funding program for intercity and commuter rail would provide consistent funding necessary to maintain existing assets and develop new rail infrastructure. This new program could potentially fund a portion of Gateway Program costs, as well as provide Amtrak with funding needed to address repair backlogs and meet the railroad’s plans for national and regional service extension beyond the NEC. (See Figure 1). The program could also support conventional intercity rail expansion projects, such as the Transforming Rail in Virginia program, a $3.7 billion project aimed at doubling passenger rail service in Virginia. And it could catalyze high-speed rail projects still in development, such as the Cascadia High Speed Rail Project, which aims to connect Portland, Oregon, Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia.

Transit

Another component of the American Jobs Plan allocates more than $85 billion to bus and rail transit systems, essentially doubling existing federal transit funding. Major metropolitan areas such as Southern California, specifically Los Angeles County, are experiencing much of the need for expanded public transportation funding. With the 2026 FIFA World Cup and 2028 Summer Olympics being held in Los Angeles, as well as major population growth expected in the region, the Los Angeles metro area is expected to spend more than $60 billion over the next several decades to expand and maintain its transit services. This includes a massive effort to convert the agency’s bus fleet to battery electric buses, which aligns with the Biden administration’s greenhouse gas emission targets.

Federal proposals to establish a new funding program for intercity and commuter rail would provide consistent funding necessary to maintain existing assets and develop new rail infrastructure.

By using federal funding to expand and maintain transit service across the country, with a targeted focus on buses and bus electrification, the administration is looking to encourage projects and programs that contribute to the goals of equity and sustainability. This need can be seen inside the Capital Beltway itself, where the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s repair backlog makes up almost 70% of the agency’s 10-year capital needs, forecast at over $15 billion.

The previously mentioned Capital Investments Grants program is another the government could reconsider. It is one of the most complex discretionary grant programs in the federal government, with many requirements for planning, project justification, funding and financing, and delivery over a multiyear period. For projects meeting minimum thresholds, it could simplify the application process to grade them on a pass/fail basis to determine which qualify for funding. The INVEST in America Act, which is pending in the US House, includes broader use of simplified scoring for CIG projects and allows qualifying projects to receive a higher federal match, thereby widening access to CIG grants for eligible projects.

To make more transformational progress, though, we need a wholesale rethinking of the definition of whether transit service is at or above capacity. Right now, only projects that are at or above capacity (ridership greater than 90% of available passenger capacity, or projected to be in five years) are eligible for a category of CIG program funding called “Core Capacity.” More projects could potentially qualify for funding by broadening these requirements—either by extending the horizon beyond five years or by statutorily enabling the eligibility of projects that increase capacity, reduce travel time, or increase reliability. Such changes could also provide new means of supporting capacity projects if passenger traffic does not immediately return to postpandemic levels. Congressional action to broaden the definition of eligibility for Core Capacity funding would not only increase the number of projects that are eligible, but also simplify the path for transit projects to qualify for such funding.

The administration is looking to encourage projects and programs that contribute to the goals of equity and sustainability.

Finally, it may be faster and simpler to increase funding for existing grant programs administered by the FTA, FRA, Federal Highway Administration (which also funds transit programs), and the Build America Bureau (which manages several financing and funding programs under the US Department of Transportation), rather than instituting duplicative new programs. Such streamlining would allow faster disbursement of funds to projects after passage of any infrastructure bill, as new mechanisms to administer funds will not need to be developed. In other cases, however, where significant new funding (over $1 billion)is proposed for specific categories of uses, a new program may be the best option.

Highways

The primary beneficiaries of federal transportation funding have long been state departments of transportation (DOTs), the entities most often responsible for highway and Interstate projects. Given the deteriorating condition of roads and bridges across the country, many state DOTs have turned their funding focus to preserving existing assets instead of increasing capacity. Some states that rely heavily on interstate highways for connectivity have also been forced to place more emphasis on preservation because of damage from extreme weather events. For example, Nebraska faced historic flooding in 2019, leading to almost $200 million in damage to the state highway system.

The American Jobs Plan looks to address this need by providing more than $115 billion for roads and bridges, with a focus on safety and resiliency. There are also opportunities for the federal government to highlight equity when funding roads and bridges by financing highway projects that look to reconnect communities split by construction of the interstate highway system. One example of this is the Southern Gateway Deck Park project in Dallas, Texas, in which the city constructed a five-acre park over I-35 that repairs neighborhood connections originally severed by the construction of the interstate.

Although the American Jobs Plan and other federal infrastructure proposals would inject desperately needed funding into America’s surface transportation system, it is important to maintain a long-term view. Lessons learned from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 show that stimulus funds are able to push “shovel-ready” projects through construction, but we must also consider long-term asset management when making investments. We see this need in states like Washington: after spending millions on many shovel-ready projects a decade ago, the state DOT now faces infrastructure preservation and maintenance requirements that exceed previously anticipated amounts.

After spending millions on many shovel-ready projects a decade ago, the state DOT now faces infrastructure preservation and maintenance requirements that exceed previously anticipated amounts.

Infrastructure investment is a continuous process. Congress and the Administration must create a smooth and predictable approach to addressing long-term needs. The key to long-term predictability lies in surface transportation authorization acts passed by Congress, which provide a stable funding framework for state DOTs (for example, the FAST Act), and timely passage of annual appropriations bills.

Our research has shown that federal transportation authorization bills historically have failed to find a permanent solution to shortfalls in the Highway Trust Fund. And continuing resolutions of these authorizations have left DOTs around the country with a significant amount of uncertainty in the timing and amount of federal funding. At the same time, congressional approval of appropriations bills frequently lags the annual start of the federal fiscal year on October 1, creating further delays and uncertainty. These actions make it difficult for agencies to plan for both the short and long term, causing project delays and other impacts to service.

Beyond congressional transportation authorizations, it is clear that the Highway Trust Fund itself needs reform. The federal government created the fund as a user-supported fund for highway transportation; highway users pay taxes on gas at the pump, which are then distributed to states on a formula basis. In recent years, the fund has had a difficult time remaining solvent due to the increased fuel efficiency of modern vehicles, the proliferation of electric vehicles, and the fact that federal fuel tax rates have not changed since 1993.

Most federal infrastructure proposals, including the American Jobs Plan, make no mention of increasing fuel taxes or evaluating more stable highway funding sources, such as basing user fees on the number of miles traveled rather than fuel consumption. Mileage-based fees could prove not only to be more equitable and sustainable than the current system, but the mechanism also aligns closely with the “user-pays” principle of the original Highway Trust Fund. Whereas pilots at the state level have evaluated mileage-based user fees, federal investment in evaluating these mechanisms could help to change the status quo and facilitate a coordinated national approach to implementing such fees.

The road (and rails) ahead

The American Jobs Plan is ambitious and has the potential to provide solutions to problems faced by transportation providers across the country. Whereas this plan covers many types of investment, the government needs to take further action to ensure that the funding provided is deliberate and distributed in a manner that benefits project sponsors and owners around the country.

The fund has had a difficult time remaining solvent due to the increased fuel efficiency of modern vehicles, the proliferation of electric vehicles, and the fact that federal fuel tax rates have not changed since 1993.

To reap the greatest benefit from federal infrastructure proposals, the United States must address the lack of a multiyear funding stream for passenger rail service, and streamline and coordinate the funding process to eliminate silos between FRA- and FTA-administered funding programs. The federal government should also broaden the criteria for funding public transportation programs so that expansion can occur before systems reach 90% capacity and can maintain those systems in good condition. It should prioritize funding for highway programs that make the transportation system more equitable, sustainable, and resilient. It needs to address the long-term federal funding uncertainty faced by many state DOTs by providing a consistent and sufficient source of transportation funding in multiyear authorization bills and annual appropriations bills. And finally, it should promote mileage-based user fee pilots or other funding streams to address the shortfalls in the gas tax and Highway Trust Fund.

The various federal infrastructure proposals, including the Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan, propose new dollars that would provide meaningful assistance to surface transportation projects across the country. Coupled with a shift in the federal government’s programmatic approach to prioritizing funding for transportation projects, adoption of the plan could be truly transformative in modernizing the rail, transit, and highway projects that serve the nation.