The “Terrible Engine of Destruction” That Inspired Federal Science Funding

“We are going to act with an urgency that will feel deeply uncomfortable,” wrote Department of Energy undersecretary of science Darío Gil in his November 28 letter to the community about the Genesis Mission. The mission, Gil explained, intends to build a platform that combines computing power, artificial intelligence, and quantum technologies into “the most complex and powerful scientific instrument ever built,” with the goal of doubling the productivity and impact of science and engineering within a decade. “Let’s quiet all the external noise and other distractions, and let’s act like our lives depend on our execution (because they do).”

Can the research enterprise feel any more uncomfortable? The past year’s cuts to science funding, haphazard layoffs and rehires at federal agencies, changes to the way that the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation (NSF) review proposals, and myriad threats to federal support for research universities have left many researchers demoralized. Though these recent events trigger new anxieties, the enterprise has been weathering destabilizing shifts in how research is done since at least the second Bush presidency, when initiatives modeled on the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) tacitly acknowledged that new sheriffs were arriving on the endless frontier. Since then, Operation Warp Speed, the CHIPS and Science Act, a parade of new research entities (such as focused research organizations), philanthropic initiatives, and NSF’s new Tech Labs have emerged alongside industrial research by tech corporations. Even before artificial intelligence arrived, the research system was being remodeled by society’s shifting expectations of what it should deliver.

In fast-moving and deeply uncomfortable times like this, the science community searches for a story about where we are going. Old narratives start around the Civil War, with the founding of land-grant universities through the Morrill Land-Grant Acts and the formation of the National Academy of Sciences, and then fast forward to just after World War II, when a famously gifted narrator—Vannevar Bush—wields a powerful metaphor and a convincing linear model to explain how research funding translates to public benefit. But today’s reorganization cannot so easily be mapped out or directed: It is emergent, the product of many discreet actions among a wide variety of powerful actors, inside and outside the country.

In fast-moving and deeply uncomfortable times like this, the science community searches for a story about where we are going.

I’d like to suggest a different story about how public support for science has evolved. Instead of physicists, this one involves enterprising entomologists and starts the clock in the 1870s, amid great plagues of the Rocky Mountain locust, which damaged more than $200 million worth of crops west of the Mississippi. As their citizens faced starvation, the governors of Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska met in desperation to ask the federal government to form and fund a commission of entomologists to research the locusts and explain to farmers how to protect their crops.

The commission did not ultimately fix the problem of the locust (more on that later), but it did anchor the idea that Congress should appropriate funds to scientists to solve problems. As entomologist May Berenbaum wrote in Science in a 1995 review of Connor Sorensen’s history of entomology, Brethren of the Net: “American entomologists effectively created the problem-centered approach to agriculture and in the process contributed more profoundly to the development of an American science infrastructure than any other single group of biologists. Entomologists played a critical role in establishing and administering the American Association for the Advancement of Science, still the premier scientific society in the country, … for creating the concept of the specialized scientific journal, and for establishing the tradition of federally funded research.” Entomologist Jeffrey Lockwood reaches a similar conclusion in his excellent book, Locust: The Devastating Rise and Mysterious Disappearance of the Insect That Shaped the American Frontier. Even science historian A. Hunter Dupree, in Science in the Federal Government, argues that the locust commission was “important” for its emphasis on problem-solving and the fact that, once established, it did not go away but continued to get funding.

When red-legged grasshoppers and self-taught entomologists are the protagonists of publicly funded science, you get a different story about the enterprise than the one centered on J. Robert Oppenheimer meeting Vannevar Bush. Rather than the discrete task of engineering a bomb or a moonshot, the war on locusts involved developing one ultimately essential element after another—from commissions, to organizations, to journals, to federal support. And when the enemy is a locust, rather than a rival military power, we can more clearly see the complicated politics around social welfare in the United States—as well as an uncannily contemporary portrait of grasshoppers as an environmental issue. And finally, as Lockwood explains, it is a story of collective science and sensemaking—in contrast with the Manhattan Project, which was conducted entirely in secret.

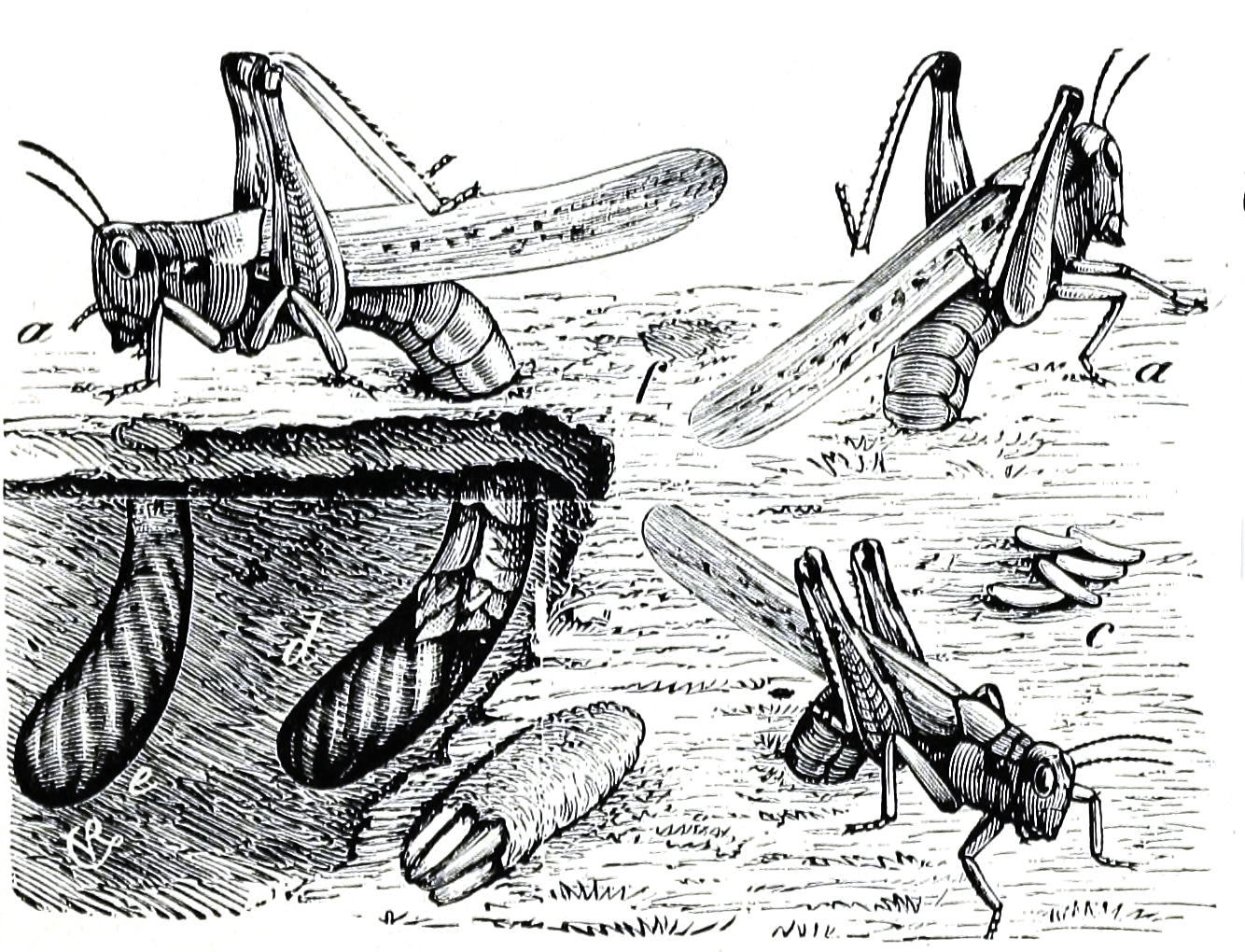

The three entomologists who comprised the commission enlisted hundreds of observers to answer surveys during the summer of 1877. Their 800-page report, the First Annual Report of the United States Entomological Commission for the Year 1877, contained maps, life-cycle drawings, and schematics for locust-killing inventions. It included observations from everywhere and everyone, including a note that at 8:30 a.m. on June 16, 1877, a professor at the University of Nebraska recorded that the temperature was 100 degrees, the wind was to the south, and the swarm of locusts that had landed for the night became airborne. Around noon, he calculated that the locusts were traveling north at five miles per hour in a swarm nearly a mile high, estimating that no fewer than 124,543,800,000 individual locusts passed over Lincoln, Nebraska, that day.

Scientists and observers worked together to create a portrait of the locust’s natural history, geographic spread, and inner organs. “Muscular, gregarious, with powerful jaws, and ample digestive and reproductive systems; strong of wing and assisted in flight by numerous air-sacs that buoy—all these traits conspire to make it the terrible engine of destruction.”

Rather than the discrete task of engineering a bomb or a moonshot, the war on locusts involved developing one ultimately essential element after another—from commissions, to organizations, to journals, to federal support.

They documented some of the “laws” that governed their behavior—the “permanent zone” where they seemed to originate in the Rockies, the way they rode the wind, the nature of their egg-laying, and the insight that their swarms had no kings or queens. To assure farmers that locusts could be food in times of starvation, entomologist Charles Valentine Riley cataloged his experiences eating thousands of immature locusts in broths, as well as mature ones in a fricassee. As mandated by Congress, the commission shared its knowledge with farmers by means of circulars. Riley wrote that the commission saw its job as meeting the public demand for “more light on the locust problem, which was to a great degree involved in darkness and mystery.”

Today, in the wake of a global effort to come to a collective understanding of the social and scientific consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the entomological commission offers a lesson in science as communication. The entomological commission gathered information from hundreds of local experts who could later disseminate the report’s findings. The report also provided a way for lay people, scientists, and decisionmakers to see how knowledge of the mysterious insect was developed. Finally, the circulars helped farmers separate worthy protection strategies from those that would waste time and money. The commission not only engaged the public in creating and understanding their findings, but also in disseminating and acting upon them.

The commission not only engaged the public in creating and understanding their findings, but also in disseminating and acting upon them.

The story of how the federal government came to fund science to solve this particular problem also offers deeper insights into the relationship between science and the American public. After the locusts devastated Nebraskans’ corn during the drought year 1874, local newspapers downplayed the damage for fear it would discourage investment and new settlers. As winter neared, an estimated 10,000 people in Nebraska alone were close to starvation, but across the grasshopper states deeply held ideals of independence, self-reliance, and moral hazard prevented governments and charities from helping farmers. “What destitute homesteaders needed was stronger moral fiber, not a handout,” writes Lockwood—a typical example of the many arguments that state and federal leaders employed to explain away the necessity of helping locust victims.

Nearly 150 years later, these same arguments are still being used to talk about health care, drug abuse, climate mitigation, and sometimes even disaster relief. Amid widespread suffering, when the state governors met in 1876, they recognized that because so little was known about the locusts, it was possible to ask the federal government for money for research as a compromise—a morally neutral request. The goal of doing science enabled a shift in focus from taking care of people to taking care of goods. If the federal government was going to support the upkeep of harbors and rivers to move crops to market, Minnesota governor John S. Pillsbury said, “surely the rescue of those crops is no less an object of its rightful care.”

Once that research got going, the locust’s story resonates with some of the paradoxes of science policy today. For example, the formation of the entomological commission and their three long reports is not what ended the plagues. Instead, the locusts went extinct, as if by magic, over the next 30 years. Nonetheless, the tradition of funding scientific inquiry to solve problems, once begun, has persisted.

And in unraveling the story of their extinction, it’s possible to see that the problem of the locusts has attributes that feel decidedly contemporary—what we might now call a wicked problem. The devastation caused by the giant locust plagues of the 1870s was tightly coupled with environmental changes. In particular, the homesteaders’ approach to monocropping corn created a single economically significant crop that locusts found very tasty. Meanwhile, drought in the early years of the decade massively increased the size of the locust swarms, which led them to eat more of that corn.

It would take decades for scientists to understand that some grasshoppers undergo a phase change from solitary to gregarious swarmers when environmental conditions shift. In normal times, solitary grasshoppers in the permanent zone in the Rockies laid eggs that produced solitary grasshoppers. But during a drought, when food was scarce, they clustered around food—and the constant jostling and accumulating excrement caused females to produce eggs predisposed to becoming gregarious migrators. This evolutionary adaptation had enabled the grasshoppers to avoid dying off during drought years. But once settlers in the permanent zone ploughed, planted alfalfa, and grazed cattle alongside the streams where the locusts bred, this cycle failed, and their eggs desiccated during cold winters. This combination, Lockwood argues, led to the extinction of the Rocky Mountain locust shortly after 1902, affecting “ecosystem processes on a scale equivalent to the [extinction of] bison.”

By looking more closely at the locust, the enterprise can begin to examine how powerful people, powerful interests, and ideologies affect the landscape of science.

Even if the scientific explanation arrived long after the fact, a unique combination of technology, human behavior, and frontier ideology hastened the demise of the pest. Locust-wise, the frontier was limited. Or, as one of the section breaks in the commission’s first report was labeled: NO EVIL WITHOUT SOME COMPENSATING GOOD.

With the history of the locust as a template for the development of publicly funded science, collaborative sensemaking, questions around social safety nets, and wicked problems become central, rather than peripheral to the way we understand the relationship between science and the public. By looking more closely at the locust, the enterprise can begin to examine how powerful people, powerful interests, and ideologies affect the landscape of science—and take action in shaping what comes next.

One obvious lesson of the locusts is that states are places where transformative ideas about the relationship between science and the public can emerge. This issue features two such stories. In Texas, voters went to the polls in November 2025 to resoundingly support funding for biomedical research, bringing their total commitment to $9 billion since 2007. This “Texas-sized” investment was first aimed at cancer and is now directed at dementia and other brain disorders. Kenneth M. Evans, Kirstin R. W. Matthews, and Heidi Russell write that it is also “Texas-shaped,” with unique geographic and political considerations influencing its architecture over the years.

In North Carolina, Jeffrey Warren and Blair Ellis Rhoades report that a 2017 initiative to create a bridge between the legislature and the state’s public and private research institutions has funded more than 700 research projects spanning environmental science, public health, education, energy, and infrastructure. After nearly 80 years of federally driven science policy, the stories in this issue show how states may be able to offer new models to connect the research enterprise with the public’s needs.