The Story Is Yours, Too

Brandon Keim engages with the work of artist Joe Feddersen.

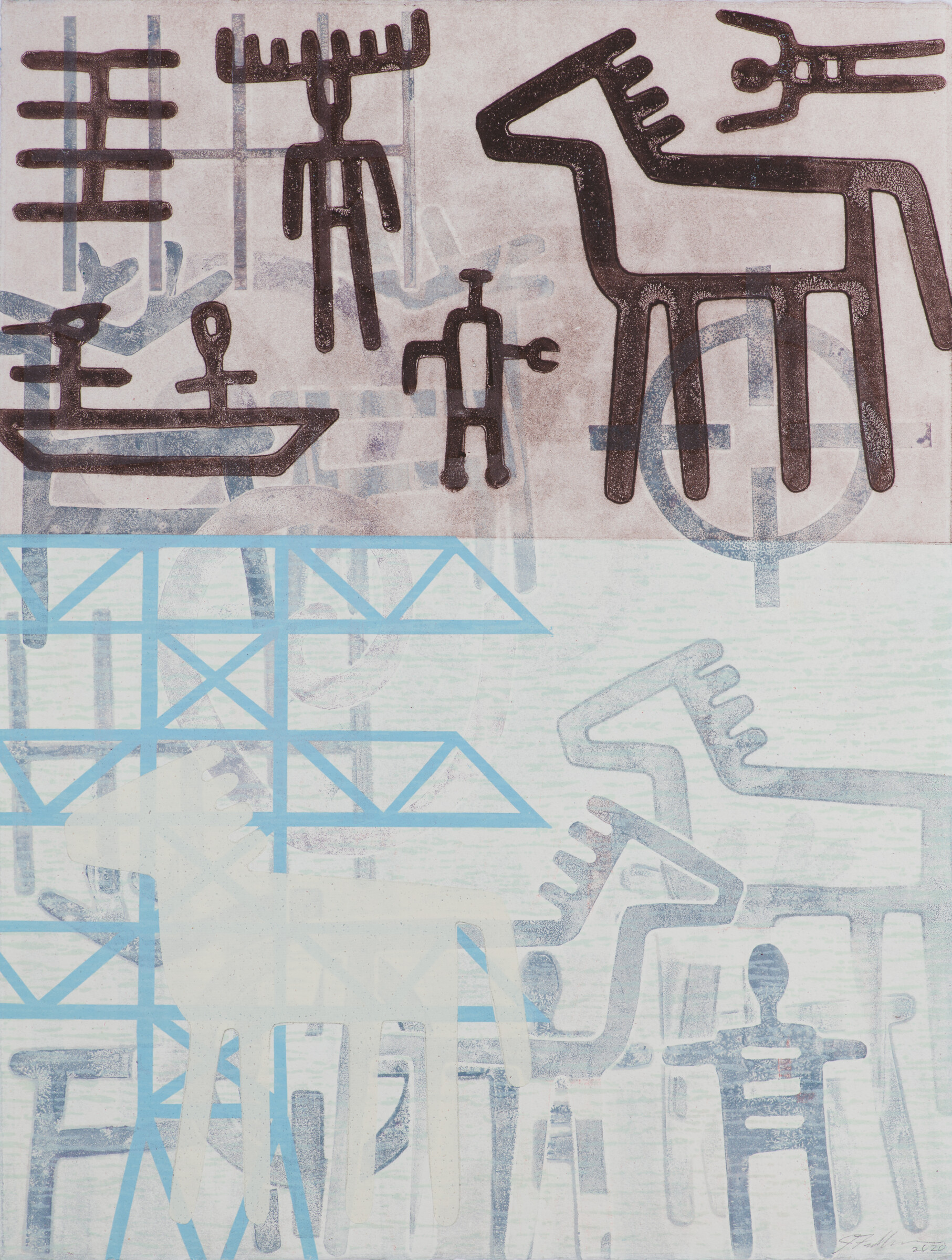

Three figures dominate artist Joe Feddersen’s print Omak Lake 2: a deer, or perhaps a ram, head extended toward the outstretched arm of a human with a turtle-like torso—or are those stylized lungs?—and below them is a horse, all traced in thick black iconographic lines. Beside the horse is another ram, outlined in a haze of pink, apparently made with a stencil and spray paint. Looming behind them is an assembly of triangles and rectangles in the unmistakable form of a high-voltage transmission tower. Behind the tower are the ghostly outlines of two more people, each holding a staff.

The figures have the character of ancient petroglyphs. So does the electrical tower, but it is a symbol of modernity, the very spine of twenty-first century civilization. Perhaps the juxtaposition is the point: what once was never entirely went away. Or maybe the message is of transcendence, of the relationships signified by those figures, their connections not only persisting but prevailing in a world disfigured by industrial appetites.

What does it all mean? When I ask, Feddersen, a renowned Native artist, explains that his work encourages personal interpretation.

“When you think about Native narratives, a lot of times they’re meant to bring up other things. People are able to tie the work to their own experience,” Feddersen says. “I’m hoping people can make that jump—that it can transcend my personal meaning and ignite something in their own imagination.”

Feddersen’s permission arrives at a moment of Indigenous resurgence. Tribes across North America are asserting their promised sovereignty and celebrating their cultural heritage—which is not exactly a new development, but rather the latest chapter in a centuries-long saga. What does seem new, though, is the interest that non-Indigenous people are showing in cultures seen as promising an alternative to industrial societies and their legacy of ecological damage, climate change, and brutal social inequalities despite unsurpassed material wealth.

Yet with that interest comes a tension: How should someone from outside Native cultures and traditions engage with and understand works by Native artists? This goes far beyond the usual tension between an artist’s intent and viewer’s interpretation. It touches on centuries of genocide and marginalization, of people degraded even as their material culture was stolen—sometimes literally, with heirlooms displayed as museum artifacts, and sometimes indirectly, as with tribal patterns turned into an aesthetic slapped on T-shirts and upholstery.

Indeed, Feddersen once wrote that Native art could not be separated from knowledge of the stories, the rituals and ceremonies and history that informed it. “The fact that material aspects of our culture are an acquirable commodity and open to redefinition by outsiders is a part of colonization, which rationalizes all that has been changed by violence and aggression,” he wrote with poet and artist Elizabeth Woody, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, in their 1999 essay “The Story as Primary Source.” They called this decontextualized consumption a “voyeuristic view.”

Feddersen once wrote that Native art could not be separated from knowledge of the stories, the rituals and ceremonies and history that informed it.

By that time Feddersen, who was born in 1953 and grew up in Omak, Washington, near the Colville Indian Reservation—he is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, a group of twelve tribes including his mother’s Okanagan—had become one of the most influential living Native artists. Renowned for his use of ancient Plateau Indian aesthetic traditions of geometric abstraction to depict modern landscapes in the mediums of print, basketry, photography, collage, and glass, Feddersen’s works have been displayed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and can be found in the collections of Microsoft and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others.

In 2009 he left his teaching position at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, and moved back to Omak, where his people estimate they have lived for between 10,000 and 20,000 years. It is there that I reach him by phone one summer morning, hoping he can walk me through some of the works—the stories—displayed in the National Academy of Sciences’ exhibition Terrain: Speaking of Home.

Feddersen tells some of those stories. “There’s this legend that talks about when the cedar tree taught the weaver how to weave,” he says. “When the weaver became competent, the cedar tree asked them to portray the world around them.” The resonance of this story is made visible in infrastructural motifs like those found in Cell Phone Tower, a white cylinder of blown glass made in the shape of a root storage bag and etched with the titular figures. The towers’ geometries also reference his people’s petroglyphic art, as do the rocket ships and space aliens and biohazard symbols of Space Ship, a waxed linen basket woven by Feddersen. “We have lots of stories about people coming from the stars and coming to Earth and being part of legends,” he says.

His people looked to the heavens, too. Feddersen mentions a tribal elder who likes to talk about how they have long known the atmosphere contains multiple layers, “because Coyote had to go up through three layers to get fire. She gets a kick out of the way that scientists just found that out. We knew that forever.”

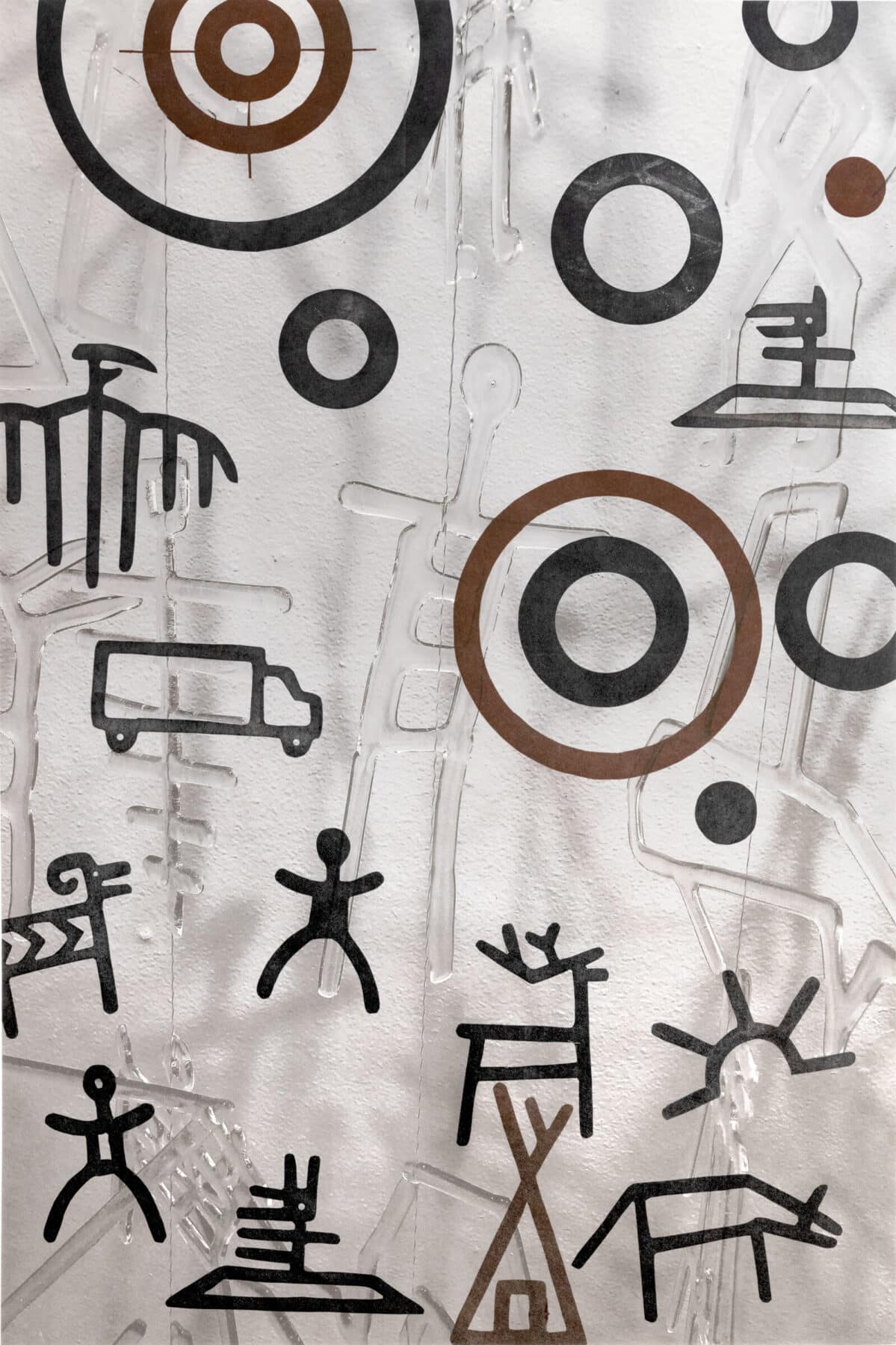

Petroglyph influences appear again in the bighorn sheep and teepees and big box trucks of the prints Echo 10 and in the horses and elk of Inhabited Landscapes 4—the latter washed with greys and mauves recalling the smoke-filled skies that are now a fixture of western fire seasons. On the subject of wildfires, made larger and hotter by a changing climate, I try to draw Feddersen out a bit. Beyond the broad histories that shaped these works, are there specific stories, specific meanings I should find? Perhaps lessons about how traditional practices and values can help people navigate the modern world, even heal it?

“There’s this legend that talks about when the cedar tree taught the weaver how to weave,” Feddersen says. “When the weaver became competent, the cedar tree asked them to portray the world around them.”

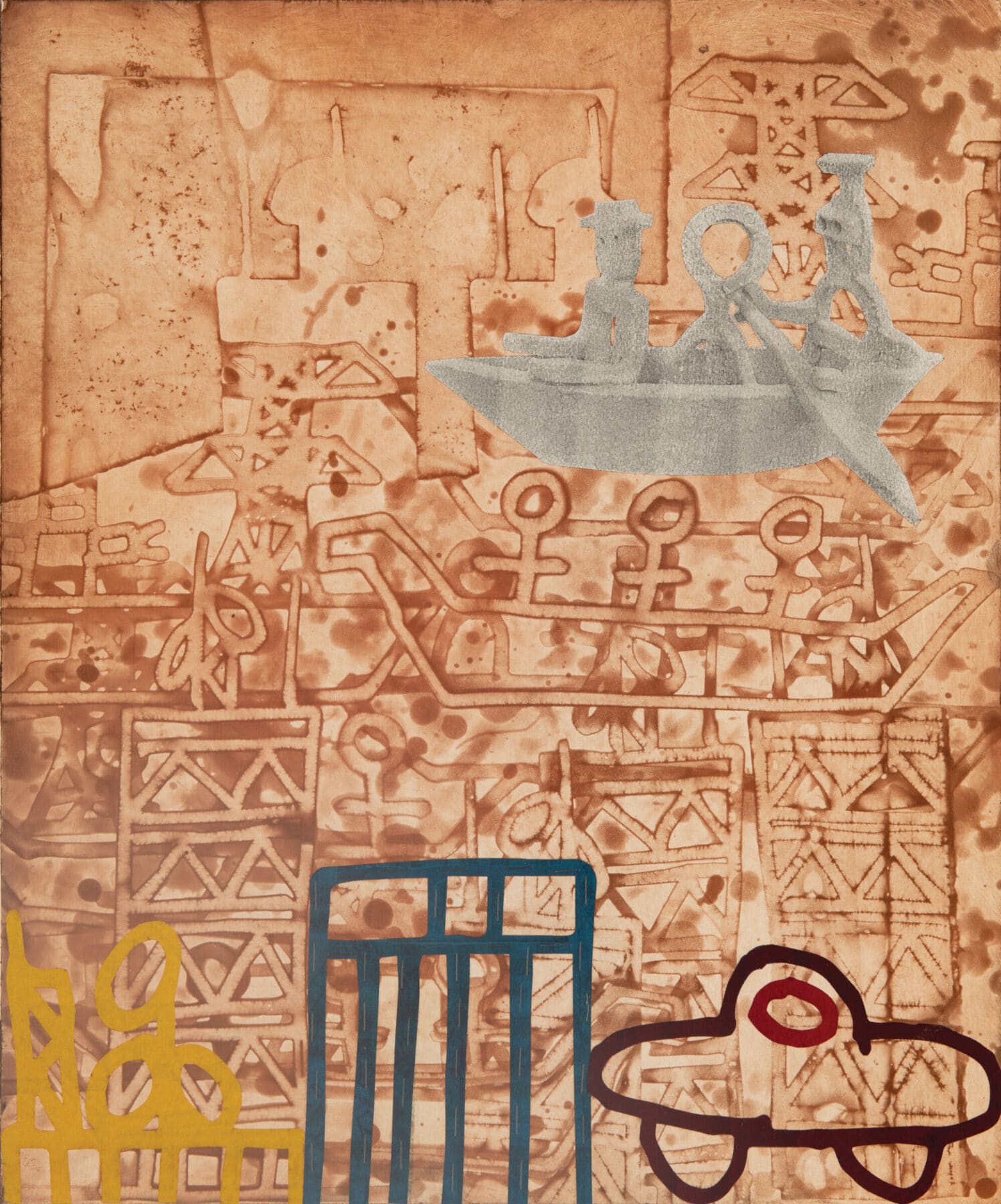

Feddersen shies away from the didactic. It is up to the viewer to make the meaning, he says, and he seems pleased as I describe my favorite of his works: Floating By, a spray-painted collage that resembles a section of graffitied gas station wall. A dripping orange line bisects the print, obscuring a pickup truck, and above it floats a boat containing three petroglyphic figures: a frog (or is it a bear?), a human, and something unrecognizable—maybe an alien? There is a whimsicality to them, a jauntiness reminiscent of Japanese candy wrappers, and also a poignancy, and I imagine them as three friends in a modern-day Noah’s Ark, afloat in a flood of fast-food chains and the sprawl of late capitalism, carrying the seeds of something better.

“All my work is about the world around me,” Feddersen says. “What I’d really like people to think about is, how do they interact with the world around them?”