Fostering Innovation to Strengthen US Competitiveness Through the National Science Foundation

In reshaping the National Science Foundation and other institutions to best support innovation, policymakers should apply evidence-based principles drawn from scholarship and previous experience.

Technology innovation is one of the twenty-first century’s key economic battlegrounds. After decades of concern that America’s competitiveness in the global economy is at risk, China’s economic expansion—coupled with the recent military conflict in Europe—have heightened the exigency of debates about America’s leadership in innovation in both economic and national security-related realms.

Against this backdrop, Congress is engaged in complex negotiations to resolve differences between the Senate-proposed United States Innovation and Competitiveness Act (USICA), passed on June 8, 2021, and the House of Representatives-proposed America COMPETES Act, which passed the Senate on March 28, 2022. The proposed legislation has implications for many federal agencies, in particular the National Science Foundation (NSF), Department of Energy, and National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Although both USICA and COMPETES echo calls for NSF to be more transformative and less conservative, their visions for achieving this are different. USICA proposes the formation of a new NSF Directorate for Technology and Innovation with new funding of $26 billion for fiscal years 2022 to 2026. COMPETES, by contrast, proposes to create a new NSF Directorate for Science and Engineering Solutions with funding of $13 billion during the same timeframe. NSF recently announced its own preliminary idea for a new directorate called Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships (TIP). The future of NSF’s new efforts to foster innovation, however, will hinge on a confluence of USICA and COMPETES, which is anticipated to occur when the bills are conferenced and passed into law later this year. As acknowledged by NSF director Sethuraman Panchanathan: “We look forward to the passage of the Bipartisan Innovation Act, which will be the next critical step in ensuring TIP can generate a transformational evolution in translating America’s research to expand our economic leadership in the technologies of the future.”

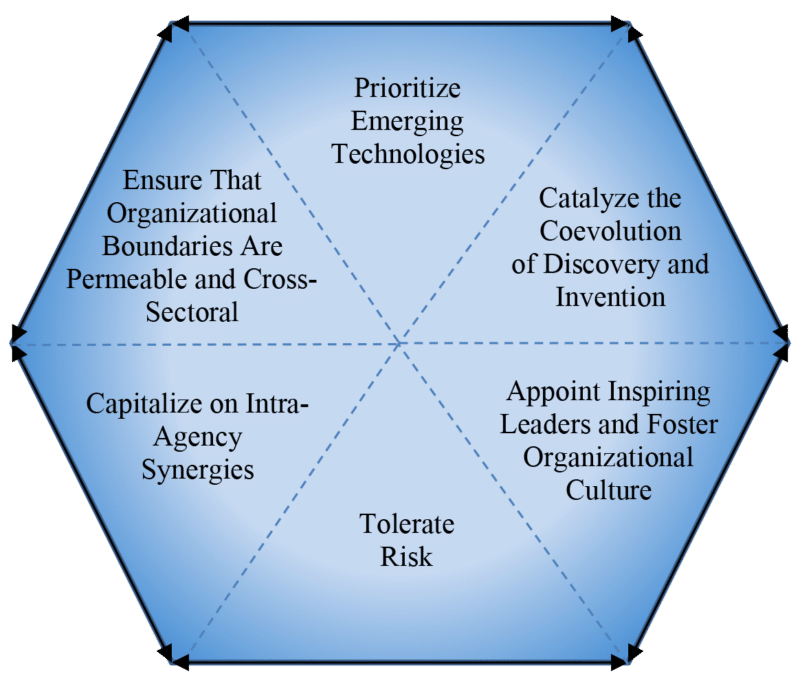

Creating the conditions for an institution to accomplish these innovation goals will be a difficult and complex endeavor. Drawing from scholarship about the drivers of the innovation process, as well as our own leadership experiences at research universities, industry research laboratories, and national laboratories, we offer six evidence-based principles for an “organizational architecture” to guide institutions engaged in promoting innovation. Although we operationalize the six principles in terms of the new NSF directorate, they may also apply to existing NSF directorates and other governmental agencies as well.

As a theme uniting these principles, we believe that American competitiveness—and the effectiveness of NSF’s new directorate—can be maximized by fostering breakthrough innovations. This requires conceiving, developing, and successfully deploying novel and valuable products, processes, or services that have dramatic societal and economic impact by reshaping the competitive market in a single industry or by launching a new industry. Historical examples of breakthrough innovations are the transistor, the laser, and the integrated circuit. More recent examples include the iPhone, high mobility transistors for 5G, and discovery of the blue light-emitting diodes central to solid state lighting.

We believe that American competitiveness—and the effectiveness of NSF’s new directorate—can be maximized by fostering breakthrough innovations.

Breakthrough innovations are different from more incremental innovations such as software for the iPhone. While both types of innovations are vital, breakthrough innovations can play an outsized role in driving national competitiveness by spawning platform technologies (e.g., the integrated circuit, on which a plethora of computer technologies were rapidly developed) that result in rapid scale-up of associated technologies, creating high-quality, high-paying jobs. We also emphasize breakthrough innovations because they are consistent with NSF’s mission to protect the nation’s long-term technological future and stimulate the industrial manufacturing base.

An Organizational Architecture for Innovation: Six Principles

1. Prioritize emerging technologies. The process of increasing the nation’s competitiveness must start with setting broad societal “meta goals,” such as developing technologies to address climate change and public health (e.g., diagnostics, vaccines) or technologies critical to economic competition (e.g., quantum computing, artificial intelligence). Applying this logic, the NSF directorate’s mission should be guided by pursuit of critical and emerging technologies to address such societal challenges and promote economic competitiveness.

But the question of how those meta goals and emerging technologies are selected is pivotal. USICA recommends that the Directorate for Technology and Innovation create an interagency working group, led by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), to coordinate activities and review key technology focus areas across all federal agencies. COMPETES recommends that the Directorate for Science and Engineering Solutions be guided by an advisory committee, as is the practice for existing NSF directorates. We believe that those bodies and the preliminary lists of technology focus areas contained in the legislative proposals will soon prove too constraining as the pace of technology development continues to accelerate.

Instead, we suggest that the new directorate utilize a rigorous process involving the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) and other groups, such as the National Security Council, along with periodic guidance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, to articulate and update technologies and targets. Under the management of OSTP, the NSTC “is the principal means by which the Executive Branch coordinates science and technology policy across the diverse entities that make up the Federal research enterprise,” and is thus able to leverage its ability to convene interagency committees. The new directorate should make use of the broad expertise at its disposal to regularly evaluate target technologies, free from constraining lists of technology focus areas like those in COMPETES and USICA.

2. Catalyze the coevolution of discovery and invention. In pursuing emerging—or re-emerging—technologies, the working group participants must embrace a methodology involving cyclical coevolution of discovery (the creation of new facts and knowledge about the world) and invention (the accumulation and creation of knowledge to devise a new tool, device, or process that accomplishes a specific purpose). Coevolution refers to an interdependent system of discoveries, inventions, and implementations that are simultaneously changing and adapting to each other over time. This coevolutionary approach transcends antiquated, if not flawed, beliefs about the dichotomy and linear sequence of basic and applied research.

The new directorate should make use of the broad expertise at its disposal to regularly evaluate target technologies, free from constraining lists of technology focus areas.

The new NSF directorate must, by design, have an enhanced focus on the engineering side of the discovery-invention cycle and a balanced framework between discovery aimed at scientific understanding and research aimed at inventing the technological future. Such a symbiosis of discovery and invention hearkens back to earlier times when industrial research and development labs in the United States (e.g., Bell Labs) were oriented toward both. In an earlier piece, one of us (Narayanamurti) outlined in detail a historical illustration of the cyclical coevolution of discovery and intention, presenting the key events and interdependencies that spawned modern information and communication technologies.

NSF already has a track record of successfully fostering this cyclical coevolution, as reflected in the “Linking Discovery to Innovation” planning framework that has been used by NSF-funded Engineering Research Centers (ERCs). The framework fosters synergies among fundamental knowledge (i.e., discovery), enabling technologies, and the invention of engineered systems or commercial prototypes. Fueled by block funding offered to a substantial number of researchers for a relatively long period of time (typically 10 years), ERCs have a record of generating substantial advances in innovation. Data from the inception of the ERC program in 1985 through 2009 show that federal support of ERCs produced significant innovation dividends during that time: ERCs produced 1,700 invention disclosures, generated 621 patents, spawned 2,097 patent and software licenses, and spun off 142 firms with 1,452 employees.

3. Appoint inspiring leaders and foster organizational culture. Both COMPETES and USICA emphasize the importance of the new directorate’s leadership. It is vital to recruit talented leaders who have transdisciplinary backgrounds in physical and life sciences, engineering, and technology, as well as entrepreneurial experiences in startups, knowledge of the corporate innovation process, or both. Top leaders must, in turn, recruit, inspire, and empower outstanding program managers. All leaders must have an awareness of NSF and its organizational culture, yet also have latitude to exercise managerial discretion. The directorate’s operation must be conducive to transcending the basic-applied dichotomy and have a critical mass of researchers on funded projects to enhance team-based exploratory technological development and to find critical pathways for eventual commercialization. Leadership appointments must emphasize continuity and should be sufficiently long to establish and maintain the institutional sustainability of the new directorate, which is likely to have a large and complex budget.

The new NSF directorate must, by design, have an enhanced focus on the engineering side of the discovery-invention cycle and a balanced framework between discovery aimed at scientific understanding and research aimed at inventing the technological future.

The directorate’s leadership team must orchestrate an organizational culture that instigates creative thinking and inspires such thinking among the directorate’s stakeholders, including researchers, staff, entrepreneurs, and industry partners. Leaders must convene individuals with diverse backgrounds and cultivate an atmosphere where trust, constructive contrariness, acceptable failures, and a sense of urgency to produce desired innovation outcomes are nurtured. There must be healthy cross-fertilization of ideas, as well as the freedom to scrutinize them. Leadership must also be committed to the operational effectiveness of the directorate, which includes equitable relations, mentoring, and a sense of accountability through rigorous annual performance reviews.

4. Tolerate risk. Leaders of a new NSF directorate must take the reasoned risks required to pursue transformative research and breakthrough innovations. Regarding risk tolerance, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) model is often revered for successfully tackling specific defense-related challenges. The new directorate, however, should not unreflectively emulate DARPA. Instead, it should employ select features of the DARPA model, including a willingness to make high-risk, high-return investments and a reliance on strong program managers who are able to make decisions flexibly.

Because it is linked to NSF’s broader purpose of advancing science and engineering, the new directorate should have a more integrative remit of both discovery and invention that goes beyond DARPA’s use-inspired emphasis. The new directorate must avoid being overly constrained by either a tendency to fund incremental and less risky research or DARPA’s Heilmeier Catechism, which encourages the articulation of a narrow question, an answer to it, how much will it cost, and how long it will take. This is why we favor the USICA nomenclature of “Directorate for Technology and Innovation” over the COMPETES label of “Directorate for Science and Engineering Solutions”—the “solutions” label is limiting. The new directorate must not simply pursue solutions to limited-scope technical projects. Instead, by minimizing limits and constraints, it can work to harness the full breadth of both discovery and invention.

As part of the coevolutionary discovery-invention process, leaders must also embrace the short-term risks of a methodical, and sometimes lengthy, process of question articulation, empirical refinement, and answering. This approach has been described as “emergent discovery.”

The new directorate should have a more integrative remit of both discovery and invention that goes beyond DARPA’s use-inspired emphasis.

One product of emergent discovery was the breakthrough in developing mRNA vaccines for COVID-19. This example illustrates how breakthroughs can emerge by beginning with highly speculative what-if conjectures such as, “Could mRNA be used as a new drug modality?” The purpose of the conjecture was to “frame and aim” the exploration; it was not required to focus on a specific problem, nor did the question need be correct to be useful. Each cyclical iteration of posing a hypothesis and empirically confirming, refining, or abandoning it eventually resulted in an accumulation of knowledge, methods, and technical tools that led to vaccines based on the mRNA platform. The new NSF directorate must be sufficiently inclusive to incorporate coevolutionary processes involving emergent discovery.

5. Capitalize on intra-agency synergies. The organizational design of the new directorate should explicitly include collaboration with other NSF directorates. Many have ongoing innovation programs that can provide valuable lessons for future endeavors. In particular, we encourage exploring coordination with NSF-funded interdisciplinary research centers, especially the Science and Technology Centers (STCs); Division of Materials Research, Science and Engineering Centers (MRSECs); and the ERCs. The new directorate should also integrate fundamental science and engineering research, enabling technologies, and commercial prototypes that emerge from STCs, MRSECs, and ERCs, as well as existing educational programs like NSF’s Innovation Corps. NSF’s new Convergence Accelerator is another promising mechanism to promote such integration, which merits further encouragement and monitoring.

6. Ensure that organizational boundaries are permeable and cross-sectoral. The design of the new directorate must involve a network of external partners, embodied in an advisory board comprising individuals chosen on the basis of their experience in research and technology institutions, for-profit companies, philanthropic organizations involved in science and technology, entrepreneurship, and the venture capital community. For example, as we previously suggested, advisory groups can be indispensable in identifying emerging technologies. The national laboratories, with their valuable research staffs and unique facilities, also merit opportunities for inclusion in the external network. Moreover, the National Science Board’s membership should be recomposed to incorporate the broader mission of NSF’s new directorate.

The new NSF directorate must be sufficiently inclusive to incorporate coevolutionary processes involving emergent discovery.

The organizational boundaries between the new directorate and external collaborators must be highly permeable and reciprocal. Evidence has shown the value of designating individuals, historically referred to as “industrial liaison officers,” who are accountable for managing such relationships to facilitate technology commercialization. The National Academy of Engineering (NAE) is composed of a wide range of members from academia, industry, government, and nonprofit organizations, which positions the NAE to be an independent liaison and a unique bridge organization between the directorate, academia, and industry partners.

Governance and accountability processes between the directorate and external partners must be both robust and sufficiently flexible to encourage the translation of discovery and inventions into commercial success. With complex relationships, there are inevitable puzzles of oversight of intellectual property and the need to perennially disclose and address conflicts of interest, conflicts of commitment that dilute time and effort, and conflicts of loyalty that include clashes of affiliations with domestic or foreign institutions or governments.

Once-in-a-Generation Decisions

This is a pivotal time for American competitiveness. In addition to the outcomes of immediate congressional deliberations, future policy decisions should be informed by research-based innovation principles. If federal innovation plans are successful, they will enhance America’s long-term leadership in addressing societal challenges through technology. Congress and agency leaders must make once-in-a-generation decisions that will buttress the nation in an increasingly fluid global landscape. The stakes could not be higher.