Jim was three whiskeys in when someone plunked down a red leather handbag. He looked up, shielding his eyes from the afternoon sunlight.

“I thought I’d find you here,” said a warm and officious voice.

Jim blinked, focused on the face of Molly Moore in a peach silk pantsuit. He’d noticed it at the audition. She looked like a creamsicle.

“You found me,” he said. He wasn’t in the mood to talk.

She sat on the stool next to him, ordered a vodka neat. He felt a spark of hope. Maybe she was here to apologize.

“You weren’t right for the role,” she said.

Maybe not.

“Thanks,” said Jim. “I gathered that from the suppressed laughter.”

“That doesn’t mean your career is over.”

“Please tell that to my manager.”

“I’ll call her right now.”

“She just dropped me.”

Molly’s vodka arrived. She had the grace not to reach for it right away. He knew she was processing this information in light of his divorce from Amelia, his millions in debt, and the sale of his estates. The collapse of his entire life in 12 months. When the tabloids roused themselves to notice, they called him Job.

But Molly shrugged. “Shake it off,” she said. “You’re due for a renaissance.”

“Then why didn’t you cast me?”

“Jim. It’s a romantic comedy with a thirtysomething lead.”

“I can play 30.” Immediately he hated himself for saying it, even facetiously. He changed the subject. “How did you even find me?”

“I do my research. You’re not the type for the rooftop bars.”

He nodded. “Nobody here gives a shit.” He raised his glass to the two unshaven men by the window, who lifted theirs in reply. “And if they do, Frank and Jeff will take care of them.”

There was a hint of threat in his words, but Molly didn’t look impressed. Which, in turn, impressed him. She struck Jim as the sort who could walk into any situation, dressed any kind of way—even in a peach silk pantsuit, to the saddest bar in Echo Park—and act like she belonged.

She said, “Here’s why I found you, Jim.”

Jim stared ahead and listened.

“Nobody had a streak like you in the aughts. No one. When all the other heartthrobs were emo twerps with frosted tips, you were a corn-fed dirty blonde Burt Reynolds. Straight off an Idaho ranch to a sheepskin rug in Rolling Stone.”

“‘The Good Shepherd,’” he recited bitterly. The moniker had stuck.

“Yes,” said Molly. “But it wasn’t just the looks. You were kind. Warm. Earnest. Generous. Emotionally available. Do you know how much you meant to a whole generation of girls?”

He straightened up a bit. “I have an idea.”

“Do you know how old those girls are now?”

He furrowed his brow. Where was she going with this? “A little younger than me.”

“Yes. In their early fifties. At the height of their earning power.”

Now Molly had a hungry look that Jim knew well.

She delivered her pitch.

“I’m working on a new company,” she said, “called Parasocial. Are you familiar with the term?”

He shut his eyes. “I think, but—”

“It means when fans imagine relationships with celebrities. Because they feel like they know them.”

He snorted. “Yeah, I know what that’s like.” A film flicked by in his mind: paparazzi, screaming girls, red carpets, Met Galas, Cannes shoots, Mykonos getaways. It peaked in 2008, when the last Callaway Dean movie was already out. But he kept going. He gave so much of himself for so many years. He answered letters, attended cons, hugged cosplayers, signed breasts.

Then came the prestige pictures that bombed. The indie martyrdom that no one noticed. The new franchises that never came together.

Then the Tumblr dedicated to tracking his receding hairline.

“So what,” he said, “you want me to consult?”

“No. I want you to star.”

He blinked.

Her composure melted. “Do you have any idea,” she said in a low voice, “how good holography has gotten in the last 10 years?”

When Molly told Jim the full scope of what Parasocial entailed, he barked a laugh. Then he compared it to prostitution. Molly asked frostily what was wrong with sex work. He remembered her past as an escort, too late to take it back. The vibe soured. The goodwill was gone. Still, when she got up, she left her card on the bar.

Jim drank one more whiskey before texting his driver to bring him home.

“Home” was now a one-bedroom in Malibu that Regina, a sympathetic producer, was letting him use while he got on his feet. He couldn’t stay there forever. And his driver, Patrick? How much longer could Jim afford to pay him? How many more favors could he pull to stay afloat?

He checked his mail.

Eight bills.

Four collection notices.

Three more letters from Amelia’s lawyers.

And a note forwarded by his manager—now ex-manager—from the president of a naturopathic hemorrhoid cream company called Sooth.

We would be honored if you would consider being our spokesman, said the note, handwritten on fine ecru stationery. My husband and I were quite the fans of yours back in the day.

He ripped it up and threw it in the trash. Then he sat on the edge of the couch, and—now sober—called Molly.

“Do you have any idea,” she said in a low voice, “how good holography has gotten in the last 10 years?”

The Parasocial facility was located in a wild, secluded valley in the Fresno foothills. A thoughtful and progressive architect had been at work here. The doors were rounded, the building hillocked, mimicking the rise and fall of the land around it. It reminded Jim of the Shire set in New Zealand, which added a layer of surreality. When Molly led him inside, he saw that the outer building was only the tip of a vast beehive underneath.

“There’ll be time for the full tour later,” said Molly, plowing down a warmly lit hallway, “but this is the quick one, because the designers are so excited to meet you. They’ve been working on stand-ins for years. Now they can actually work with a star.”

Jim nodded, noting the designation. He could never take it for granted again.

They passed doors, three to a side. Each had a round window.

“This is the fantasy wing, and these are the holo-chambers,” said Molly. “Each chamber will be turned over daily to client specification.”

“Like the holodeck in Star Trek.”

“Exactly. And we call your holo a ‘tangi,’ short for ‘tangible.’ Feels just like a real human. But it’s only light and force fields and trained AI.”

Jim was still trying to process. “So my tangi and the client can sit on the holo-furniture like a real couple.…”

“Sit, lie down.…” She glanced back at him. “A lot of things.”

“Can I watch?”

A beat passed before Molly answered, without looking back. “You have the option to watch.”

He noticed the hesitation. “But…?”

“But you get paid less.”

“Like, what? Half?”

“A tenth.”

“A tenth?” He stopped in his tracks.

She turned around, patient, humoring him. “Well, think about it, Jim,” she said. “Would you want someone watching what you were doing with your teenage heartthrob? Wouldn’t you pay extra for privacy?”

“I bet some people would pay a lot extra for me to watch.”

Molly raised her eyebrows and stared into space. He could practically see the lightbulb pop over her head.

“But wait,” he said. “Let’s go back to the normal option. I can’t watch, even if I’m the heartthrob in question?”

“But it’s not really you. It’s just your licensed image.”

“Not just my image. My body.”

“Not your actual body. You don’t have to do that.” There was a trace of acid in her voice.

“Fine,” Jim conceded. “My tan—tangerine—”

“Tangi.”

“Yes, that. I did read the contract.” Or the first eight pages of it, he said in his mind, until I skipped ahead to the pay clause.

Molly nodded. “That’s true,” she conceded. “And listen. We only want to do what you feel comfortable with. Me, Hiroko, Andy, Sandeep—we agreed on that at the very beginning. We wouldn’t push.”

Withholding money is pushing, Jim thought.

But he was not in a position to quibble. He didn’t even have reps anymore. His friend Lee was looking at the contract as a favor.

“I’ll think about it,” he said, and summoned his trademark wink.

“We call your holo a ‘tangi,’ short for ‘tangible.’ Feels just like a real human. But it’s only light and force fields and trained AI.”

Negotiating the initial contract took three months. Jim used the time to get back in shape. It was difficult, because the catering was generous—Molly was a film executive, after all, and she knew what “star treatment” meant. But they were using his body to design the tangis. He needed to look as good as possible for his fans. If they were going to pay $10,000 a session, they deserved it.

Physical intake lasted three more months. The designers were meticulous. He was measured, imaged, palpated, and fitted. He went through extensive motion capture. First basic positions—first, second, third, like in ballet—then more complex positions: sitting, walking, lying on his back, lying on his stomach, thrusting into midair, bent over, cross-legged, hugging a pole, on all fours. Every position would be used to extrapolate infinite intermediate positions, and of course, motion itself.

“Think of it like yoga,” joked one of the technicians.

“More like Kama Sutra,” said another tech, grinning until a sharp look shut him down. Jim noticed he wasn’t there the next day.

Then came the personality capture. The designers used all his film roles as raw data to train the tangis’ AIs, which would in turn govern how the tangis interacted with clients. They already had working prototypes, but needed to do “pick-ups” to patch gaps—just like for a film.

“Hey,” Jim called to Molly from the chair, where the designers were clustered around a promo photo from Ranch Dressing. “You can’t do this without rights to the work, can you?”

“We got them,” said Molly, hurrying over with a placating smile. “We wouldn’t dream of it otherwise.”

“You got them? All?”

“Everything we’re going to scan you for, yes.”

“So this is all Guild compliant.”

“One thousand percent.”

First Jim was scanned and de-aged as Callaway Dean, then as Michael Angstrom from Dirty Days, then The Hound Dog from Bitter, then Lancelot from Arthur’s Seat, and finally as Marcus O’Dell from Trail of Fire, the CIA agent with the eidetic memory and the heart of gold. It felt good to revisit them all, like old friends.

They also gathered data for the tangis of Jim-as-himself, at various ages. The Rolling Stone shoot on the sheepskin rug. The 2005 Gaultier suit, full mustache, no shirt. They used all his media appearances and interviews, but also made him perform hundreds of short scenarios, both scripted and improvised, from which the AI would extrapolate interactions with clients. Molly said they’d scan him for his bit roles and cameos, too, if there was enough demand.

If there was enough demand.

That was the phrase that made his heart sink. What if there wasn’t? He hadn’t worked in 10 years. He thought again of the traitorous Tumblr, the mean forums on Reddit, the snide profile on Jezebel. What if nobody wanted him?

But then he saw the eyes of a female technician, a pretty woman with cornrows and a nose ring, flick up and down his body when she thought he wasn’t looking. That gave him hope.

Every position would be used to extrapolate infinite intermediate positions, and of course, motion itself.

After the capture work came the licensing. Jim sat across from his friend Lee at a vintage Lucite desk. They had a view all the way to the ocean.

“So,” Jim began, “I want to license full spectrum rights.”

Lee lifted his eyebrows. “This is new legal territory, you know.”

“I know.”

“So you’re fine with these women doing whatever they want with your body.”

“It’s not really my—”

“You know what I mean.”

“It’s guys too, by the way.”

“Pardon?”

“‘Full-spectrum’ means anyone,” said Jim with a note of pride. “Anyone over 18 with the money to pay, whatever their gender.”

Lee was unmoved. “And you’ve waived your right to access any recording of any session.”

“For now. Makes a lot more money. We can revisit when the contract comes up for renewal.”

Lee shook his head. “You’re brave,” he said. “A part of me would need to know.”

“You’re not a celebrity. People are depraved.”

“Nah. Most ordinary people are basically good.”

“The people who can afford $10,000 a session aren’t ordinary.”

Lee shrugged. Financial insecurity was an abstract concept to him. “Not true. Take Carrie. I told her I was helping you out, and she said she used to write letters to you when she was a teenager.”

Jim was touched. He’d always thought Carrie was a neat person, tough but kind, a speech therapist who tied up her blue-streaked hair in colorful handkerchiefs. She played rugby for a local rec league. She had great calves. She was pretty hot, actually.

“Huh,” he said. “I didn’t think I was her type.”

“Well, that’s the thing,” said Lee. “You’re whatever type they need you to be.”

Jim sighed. “They’ll have me in a dog collar in no time.”

“Or maybe they just want someone to talk to.”

“Want to buy your wife a session and see what happens?”

“Don’t push it, Stone.”

Lee said it in a light tone, but Jim could hear the discomfort underneath. His joke had bombed.

His mirth dried up.

The full weight of his fear crashed down on him all at once.

He leaned forward. “Real talk, Lee,” he said. “Amelia bled me dry. I have nothing. I’ll do anything. I can’t be any more humiliated than I already am.”

“This is new legal territory, you know.”

A year later, in the same office, Lee popped the cork on a bottle of 2003 Blanc de Blanc. He rested against the edge of his desk and held out a flute to Jim, who was looking out at that same view of the ocean.

“To ‘Job,’” said Lee, echoing the nickname, which now had new meaning. “How long’s the wait list now?”

“Six months.”

“I assume you want to keep going.”

Jim laughed. “Lee,” he said. “I’ve made more money in the last year than the previous 10 years put together.”

Lee shrugged. “Just a formality,” he said. “I can see how happy you are.”

“Yeah.” Jim shook his head and got a lump in his throat. For a moment, his eyes got wet. He hadn’t realized just how desperate he’d been a year ago. He’d had a drinking problem, and hadn’t recognized it. He’d been depressed, and hadn’t recognized that either. It was so good to have his fans back. They’d showed up for him. They were flying in from all over the world—Singapore, South Africa, Saudi Arabia. He knew he shouldn’t depend on external validation for happiness. But, he told himself, his prep for Parasocial—that had been the real turnaround. Not the popularity of his tangis or the flood of money, but those simple acts of self-care that added up over time. He’d long moved out of Regina’s apartment. He had a sleek new house in Silver Lake, all smoked glass, cement stairs, and a fireplace as tall as he was. He’d paid down his debts in huge, satisfying lump sums. He was in therapy. He wasn’t dating, not yet, and that was healthy. He had reps again—but they’d made it clear to execs that they only wanted scripts that were really special. No film role, no matter how lucrative, was a drop to his Parasocial stream. Yes, it was like prostitution, and there was nothing wrong with that. Hadn’t he always sold his body? Hadn’t all actors, for all time? And now he could be generous again—to himself, to his fans, to anyone.

He sipped the champagne, closed his eyes, felt the stars in his throat.

“Anything you want to change in the contract?” asked Lee, rounding his desk, back to business.

Jim paused. “Actually,” he said, “I was thinking of making the sessions more accessible. You know, to a wider variety of people.”

“Having a nonprivate option.”

“Yeah, that costs only a tenth as much.”

“And you could watch.”

“Oh God, no,” said Jim, laughing. “This is strictly a business decision.”

“Like Mizrahi in Target.”

“Something like that.” The champagne was making Jim jovial, relaxed. He decided to revive an old joke. “Has your wife booked a session yet?”

Lee rolled his eyes. “In your dreams, pal.”

“Didn’t you say she just wrote letters to me?”

“I don’t know.”

Again, Lee’s noncommittal tone told Jim to back off, so he did. He felt a little resentful. He was making Lee piles of money too, after all, and deserved some grace.

He tried to steer the conversation back to an airy theoretical realm. “Makes you think, though,” he said, “in ethical terms. Whether it’d be cheating or not.”

But Lee was marking up clauses on his pad, and didn’t answer.

One day, Jim arrived at the Parasocial facility as usual, in a stretch SUV with tinted windows and a revolving sashimi buffet.

Per contract, he was required to visit once a month for pick-ups. Though most customers were satisfied, they reported bugs: the tangis’ sweat tasted funny, The Hound Dog glitched when laughing, Marcus O’Dell couldn’t flex his left middle finger. Plus, to Jim’s pleasant surprise, there’d been high demand for tangis at his current age, 59. He had to look current—up to and including his most recent media appearances—which Molly called “the daddy factor.” She wanted to troubleshoot as much as possible before rolling out new stars.

Parasocial was now a household name. A joke turned coup. Especially since he’d made sessions more accessible. Now bridal parties were pooling money to gift sessions to the bachelorette. Subreddits had popped up for clients to compare notes. Rolling Stone had called: they wanted Jim to revisit the sheepskin for his sixtieth birthday.

On facility visits, the driver always passed Parasocial’s main entrance on the way to the private entrance in the back. Jim could never help peeking at the clients. He and his therapist had agreed it would be a terrible idea to watch the sessions for any reason—after all, he’d opened up the nonprivate tier for his fans’ sake, not his own. But that didn’t mean he couldn’t see what kind of people paid money to spend time with his tangi. He wondered what their fantasies were. Whether they’d leave satisfied. Whether they’d return.

This time, he noticed an attractive, thick-shouldered woman getting out of a black SUV. She was wearing sunglasses and a black trench coat. Her hair was bound up in a bright scarf.

The driver heard him gasp.

“Sir?”

“Slow down a little,” said Jim.

But he regretted saying it, because as soon as his driver slowed down, the woman paused and, self-conscious, looked directly at his tinted windows. It was Lee’s wife, Carrie.

He tried to forget about it.

He was here to work. He focused on what the designers needed from him. Apparently the chest hairs on his Lancelot tangi were unstable, so the techs were going back and forth between a topless still from Arthur’s Seat and Jim’s own chest, speaking over him as if he weren’t there.

The whole time, Jim kept thinking of Carrie. Had Lee paid for her session? Or was she here without his knowledge? He thought about her scarf, her calves, her rugby muscles. He felt a black spark of curiosity in his gut. What was she doing with his tangi at this very moment?

When the others were at lunch, he called over the female technician with the nose ring, whose name was Eva.

“Do you know where the recorded sessions are, uh, kept?”

Eva paused, uncertain.

Jim plowed on, hoping to erase her hesitation. “I wouldn’t try to look at the private ones. I just.…” A new tactic occurred to him. He lowered his voice, improvised. “… I was concerned about abuse in a certain case.”

Immediately, her expression changed. “Oh no. I’m so sorry. I’ll talk to Molly right away—”

“No need,” he interrupted, letting impatience color his voice. That tone had cowed many a timid assistant in the past. “I just need a quick look.”

After a beat, Eva gave a sudden blank smile. “Got it,” she said. “The research hub is on the bottom level. Sam is the head librarian.”

“Librarian!?” He rewarded her with a return to a joking tone.

Eva smiled. “Don’t worry. It’s strictly for R&D.”

“Always improving the technology, eh?”

“Oh yeah. Molly wants the tech on demand—so anyone can sell their own tangi.”

For a moment, Jim’s head spun. “World domination, I see.”

“Totally,” Eva laughed.

“Oh yeah. Molly wants the tech on demand—so anyone can sell their own tangi.”

After the day’s pick-ups were done, Jim made his way to the bottom level and asked for Sam, who turned out to be a cheery youth with glasses and a black mullet.

“Sure thing,” said Sam, “you just need to sign here.” They pushed a pad across the concrete desk.

“Sign?” said Jim, shifting feet. He’d rather no one know he was looking at any of the sessions, even if they were nonprivate. Especially not Molly.

“This is just for our records,” said Sam. “You know, like when you access archives at a research library?”

“I don’t, but I’ll take your word for it.”

“OK great,” said Sam, with a loud laugh. This reminded Jim to go easy on the kid. After all, he was a star again. When people were nervous, it was his job to be gracious.

So Jim nodded to Sam with the same characteristic warmth he had used with Eva, and Sam visibly relaxed.

They led Jim to a small, soft-lit viewing room with a hyper-def screen set into the concrete. Sam logged in with their admin account, then showed Jim how to scroll through the library to access the session he wanted to see. Then they logged out and showed him how to make his own profile, which included only the sessions he was contractually allowed to watch. Thank God, Jim thought. Thank God there are rules to protect me from myself.

Sam left to get him coffee. Jim navigated to the day’s date—March 20—and scrolled through the sessions.

They were all grayed out. Including, he assumed, Carrie’s session.

Sam was due back any minute.

Jim made a snap decision.

He logged out just before the door opened behind him.

“It’s so weird!” said Jim, adopting the tone of a befuddled elder. “I was scrolling? Just now? And the system spontaneously logged me out.”

Sam frowned. “That’s weird. Hang on.”

Then Sam did what Jim hoped they’d do: log in as the admin. Jim had played a CIA agent with eidetic memory. He knew exactly what to do.

Sam checked a couple things, then straightened up. “Looks OK to me,” they said. “Try again? I’ll stay here to make sure it works.”

Jim logged in with his own account. It worked.

“Well, I’m just down the hall if it happens again,” said Sam. “Thanks for letting me know. We’re still troubleshooting everything.”

They closed the door.

Jim logged himself out, and logged in again with Sam’s admin password. He navigated back to March 20.

All the sessions were now available.

He clicked on the most recent one, Chamber 5F, which had just finished rendering.

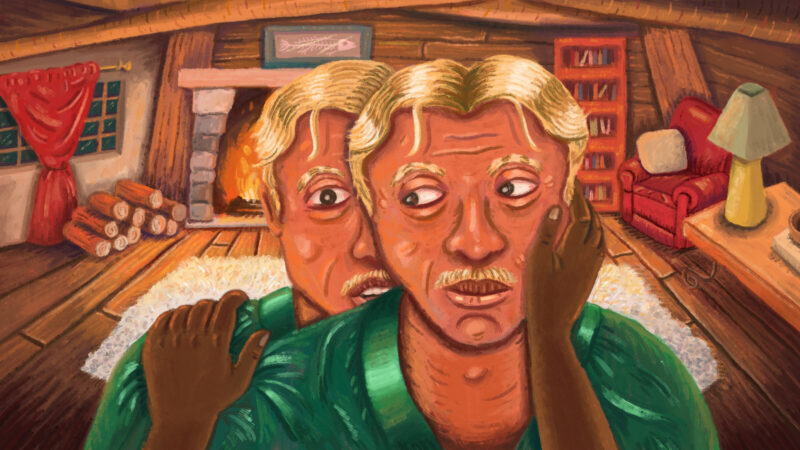

The chamber was made up to look like a high school counselor’s office.

A hot spicy darkness welled up in his groin.

“I knew it,” he said under his breath. “Bad girl.”

Onscreen, Carrie came in, tentative at first. She unwrapped her hair, took off her coat. She was taking in the scene as much as Jim was—seemingly amazed at the fidelity and touchability of the room. She read the inspirational posters on the wall, ran her finger along the books in the bookcase, shook her head. She was wearing clothes from 30 years ago—wide-legged jeans, pocket chains, skater Vans.

He realized she’d dressed as her teenage self.

Carrie straightened up and said, “Hello, Jim.”

His tangi appeared in the padded chair, dressed in an Aran sweater he recognized from a 2001 Esquire shoot.

“Nice to see you, Carrie,” said Counselor-Jim.

Jim was used to watching himself in films. But this was surreal—a film he was headlining, but had never acted in. He felt nauseated.

Carrie was disoriented too. This was why two hours was the recommended minimum session—clients had to relax into the absurdity of the situation.

“You’re real,” she said.

Counselor-Jim laughed. “Of course I am. Please, have a seat.”

Carrie sat down gingerly, as if the chair might explode. It was too small for her. She was trembling like a rabbit.

In the viewing room, Jim leaned forward in his chair. This, Jim thought. This is what overwhelming desire looks like. She’d always wanted him. This was her fantasy.

“What’s on your mind?” Counselor-Jim asked.

Her voice came out weak and breathy. “My sister died,” she said.

Jim frowned. His hand had been inching toward his belt buckle, and now he felt ashamed.

Carrie was watching Counselor-Jim very closely for his reaction. Jim realized she wasn’t full of lust. She was scared.

Counselor-Jim heaved an empathetic sigh. “Oh Carrie. I’m so sorry. Tell me what happened.”

Her face crumpled. She started crying.

Counselor-Jim leaned over to hand her a box of her tissues.

The simple gesture made her cry harder.

This was surreal—a film he was headlining, but had never acted in.

After a few minutes, Jim turned off the recording.

He felt sick to his stomach all the way back to Silver Lake. He asked himself why. In the back of the limo, he parsed his feelings the way his therapist had taught him. “Make a list,” she’d said, “and be as honest with yourself as possible.” So he got out his phone and opened a new note.

1. Disgusted with self for looking

2. Feel bad for Carrie

3. But wanted her to do sex stuff (!)

4. Mad at Lee (why?)

He looked out at the palm trees, thumping past, one by one. He felt his stomach growl, a consequence of his constant calorie restriction.

Finally he added,

5. Is that all they want me for? Talk??

A week later, that was the question that led him back to the basement.

Two months later, Jim had a ritual.

He told Sam he was watching the sessions he was getting paid to watch—true to his prediction, there’d been demand, and Molly had agreed to open up a new tier for the exhibitionist set. But these sessions were also the most boring. The clients were performing for Jim, but they were usually terrible at it, so he played solitaire on his phone until they were done. Then he logged out of his account and logged back in as the admin.

He wanted to watch the sessions he wasn’t supposed to watch. The nonprivate sessions always had an element of self-consciousness, an awareness of the possibility of being observed. In contrast, the private sessions were raw, truthful, and cathartic. At first, Jim played roulette. He never knew what he was going to get. Molly had been right: he meant so many things to so many people. He was a family friend, a mourner at the funeral, a greengrocer down the street. There were fantasies of safety, like Carrie’s; also fantasies of refusal, where the client said no and he respected it. Then—to Jim’s relief—there were the all-out fuckfests. Sometimes the holochamber was made up to look like a suburban bedroom, sometimes like the Victorian boudoir from Roses of God. Some clients arrived in couture, ready for a pre-red-carpet fuck; some arrived in sweats, ready for a homemade breakfast. He watched himself as a generous basketball coach, an obliging stepson, and, yes, a collared sub. But most of the sex was fairly straightforward: tender, comforting, affirming. The sheepskin rug was especially popular. Clients used it as a blanket, cape, brace, sponge, sling, mop, and whip. And women weren’t the only ones to book sessions. About a third of the clients were enby, queer, trans, or men. Roughly half of them returned—they weren’t here for just one session. They wanted a real, ongoing relationship.

He’d gotten used to watching himself. Especially since algorithm drift meant that there were little differences between his real self and his tangis. When he came in for pick-ups now, he made sure to act slightly differently from his real self, as if to reinforce these gaps. His tangi, for example, moaned at a higher pitch than he did in real life. This comforted him. It meant he still had an edge over his fans. They weren’t quite getting his real self, but he was getting theirs.

While he watched, he wondered where all these people had been, during the years he needed them. Had they shared the Jezebel article? Had they laughed at the Tumblr?

But now they were here, with him. And he was watching. And they didn’t know.

With each session, Jim felt a score settling. He stopped seeing his therapist. Watching these sessions was so much more healing than talking about his failed marriage could ever be.

His reps sent him a script for a prestige pic set during the Vietnam War. The director was fresh from a BAFTA win. She’d written the part for him. He’d have to be in Southeast Asia for two months.

He found reasons to politely decline.

Algorithm drift meant that there were little differences between his real self and his tangis.

One day, Jim logged in, selected a session at random, and leaned back with his coffee.

But when the image came on screen, he frowned.

It was his own former bedroom.

The door opened, and in walked Amelia.

Jim hadn’t seen her live image in more than two years. She looked as regal as she always had, ever since she first approached him at a Vanity Fair party—a journalist with a high forehead, strong nose, and huge smile. Now she was dressed in her familiar green bathrobe and slippers.

He watched with a sick feeling in his stomach.

She looked around the room, touching the pillows, smoothing the bedspread, wiping away tears.

Finally she stood at the foot of the bed and said, “Hello Jim.”

His tangi appeared, a bare leg extending over the Egyptian cotton blanket. Bed-Jim sat up and patted for her to sit.

Jim remembered this morning. It had really happened, about three years ago, before the divorce.

She said, “I gotta go, Jim.”

Jim balked. That’s not how this morning had gone. She’d had a bad dream, but he’d patted the blanket, and she’d climbed in, and they’d had great sex.

Bed-Jim cocked his head as if to say, “What?”

Yes, what? thought Jim. What the fuck is this? And why won’t the tangi speak?

“I love you,” she said, “but I can’t take this anymore.”

Bed-Jim frowned. He sat up further and again patted the blanket.

“No,” said Amelia.

Bed-Jim looked confused. He was thinking what Jim was thinking: usually that worked. Usually she came to him and he’d kiss her hand and maybe kiss more than her hand and they’d figure it out. He wasn’t used to hearing “no” from her.

Bed-Jim gave her an inquisitive look.

“What I mean is,” said Amelia, “I don’t think you can separate love from power. I don’t think you ever could. Your fans were your first relationship. Their love for you gave you control over them. That fucked you up. And when you couldn’t have an edge over them anymore, you had to have an edge over me.”

Bed-Jim was silent. Now—Jim realized—she’d requested his silence.

“All I needed you to do was listen,” she said, her voice getting thicker. “But there was no pain allowed in the house except your pain.”

No, thought Jim, that wasn’t true at all. He’d supported her throughout her career—the disappointing book reception, the layoff, the freelance years. He’d been a loving husband through all of it.

“We were both in pain!” he hissed at the screen. His eyes flicked to his tangi. “Tell her!”

But Bed-Jim only kept nodding, looking pained and sympathetic. It was infuriating. She was using him in the one way he would never consent to be used: as a muted dummy, with no mind of its own.

Amelia walked to the bed. She sat down where he’d patted.

“Now I know what I need from you. I need you to apologize. I know you’re not him, not really, but it’s the closest I’ll ever get. Say it and mean it.” She brushed away tears, laughed. “I guess I’ll have to request you can speak next time.”

Now—Jim realized—she’d requested his silence.

It wasn’t difficult to find out when Amelia’s next session was. It also wasn’t difficult, once Jim actually sat down in front of his cement fireplace and thought it through, to make a plan. He’d watched dozens of sessions by this point. He knew the protocol inside and out—how clients were escorted to the chambers, when they were left alone, what they expected from their tangis.

He only needed a bit of luck.

When Amelia opened the door to the chamber, wearing the same green bathrobe as last time, Jim was already in place.

He stayed absolutely still. He acted as a paused tangi would act.

Amelia looked confused. He prayed she’d assume that the tangi had come pre-set with the room this time, and that she would not call the tangi with the usual command of Hello Jim, in which case there would be two Jims in the room.

He preempted her by saying what he’d said to her hundreds of times before: “Morning, beautiful.”

She relaxed a bit, laughed.

“It’s weird to have you speak,” she said.

Jim steadied his nerves, knew what to do. This was just like being onstage in a play. He’d watched his tangi in so many sessions, as every possible character, including himself. He knew how to act like himself.

“You look like you want to talk,” he said, pitching his voice low for empathy.

Amelia looked surprised. “Yeah,” she said, “I do. You … remember what I said last time?”

“I do,” he said, nodding like his tangi would.

She sat on the bed in the same spot. She was picking up from last time, feeling safe. “I requested that you could talk this time, because I need you to apologize. To say it. Mean it.”

“For what?” he said.

He pitched it in such a way that it was not a challenge, but an invitation for her to unburden herself.

Amelia looked out the window—a view onto their crescent-shaped pool, reconstructed with astonishing accuracy. The designers must have visited the house itself, in Hollywood Hills. Jim began to forget that they weren’t really there. That this wasn’t really a moment from three years ago, before his life had fallen apart.

Amelia took a long time to answer. He had the sense that she was discovering new words to express herself, different from the ones she’d planned to say, surprising herself.

“For not understanding how good you have it. Even after the fame faded away. All you could see was how you were a victim. And you retook power by drawing it out of me. You couldn’t be OK, unless you were taking something away from me. I had to leave to save myself.” She took a deep breath and turned to him. “I need you to apologize for doing that to me.”

Amelia had barely finished before Jim sat up, letting the blanket fall down his chest. “I need you to apologize for gaslighting me every time I was sad,” he said.

Amelia frowned. “That’s not even what gaslighting mea—”

Then she stood up suddenly.

She knew something was wrong. Jim knew that she knew it.

She looked at the camera orb in the top corner, the one that recorded all the sessions. “Operator? Hello? This tangi is malfunctioning,” she called.

A warm, robotic voice filled the air. “I’m sorry, I didn’t recognize your command. Could you please say that again?”

“Fuck,” Amelia muttered, pulling the instructional flyer out of her robe pocket. “Pause, Jim.”

That was a command. Jim needed to go absolutely still again. He stayed in the same position, sitting up in bed, supporting himself on his hands, looking at Amelia. But now he panicked internally. When he’d seen his tangi on pause before, he was seeing it from enough of a distance that he didn’t know how deep the pause went. Did the tangi’s heart still beat? Did its veins still pulse? Did it still breathe?

Body memory clicked in. He’d played dead before. Breathe in from the sides of your core. So slow. So slow. Exhale slowly. So slow. So slow. Amelia wouldn’t know what was normal, either.

She was reading through the instructions, moving her lips to the words, a habit he’d always found endearing.

She found what she was looking for. She looked up again. “Play, Jim.”

He moved, letting himself fall back on his elbows. He opened his mouth—

Amelia said, “Mute, Jim.”

“No,” he said.

It slipped out.

Amelia’s eyes went wide.

She screamed and ran to the door.

“Operator? Hello? This tangi is malfunctioning.”

He needed to get out of here. He got up, wrapping the blanket around his naked body. He sidled next to Amelia, who screamed louder and shoved him away and ran to the other side of the room. He managed to let himself out into the corridor. He would make for his green room. And then he would get dressed, nod to his driver, get in the car, have his sashimi, go home, have a whiskey, and call his therapist, like he really should have done in the first place.

The elevator doors opened onto a tableau of three faces.

Sam and Eva, looking incredulous.

Molly in a marigold pantsuit, fists clenched.

The lawsuits took everything. The tabloids feasted for a month, and then moved on.

Jim moved back into the one-bedroom flat in Malibu. Regina had left a box of gluten-free bagels tied with string, and an envelope with her handwriting: Just in case. He opened it. Inside was an old handwritten note on fine stationery, taped together.

He recognized it now. The invitation from Sooth, the naturopathic hemorrhoid cream company.

He called the number at the bottom and listened to the phone ring.

I would be honored, he recited in his head.

Say it. Mean it.