This story was originally published in Slate in September 2023. It is republished here as a part of the Future Tense Fiction project, presented by Issues in collaboration with ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination.

Author’s note: I wrote “Little Assistance” in the spring of 2023, and at the time, I was struck by how much influence private corporations were set to have in Moon governance—far beyond what I’d seen in classic sci-fi. In 2023 alone, SpaceX set a new record with 96 orbital launches. In the story, Eugene feels pressure from both the US judiciary and the private company running the Moon base, but the corporate influence looms larger. If I were writing this story in 2024, Eugene’s sense of the private sector’s power would probably be even greater. Over the past year, companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin have made significant strides in lunar missions. It feels increasingly likely that future Moon bases will be viewed as corporate facilities rather than extensions of nation-states subject to traditional legal principles.

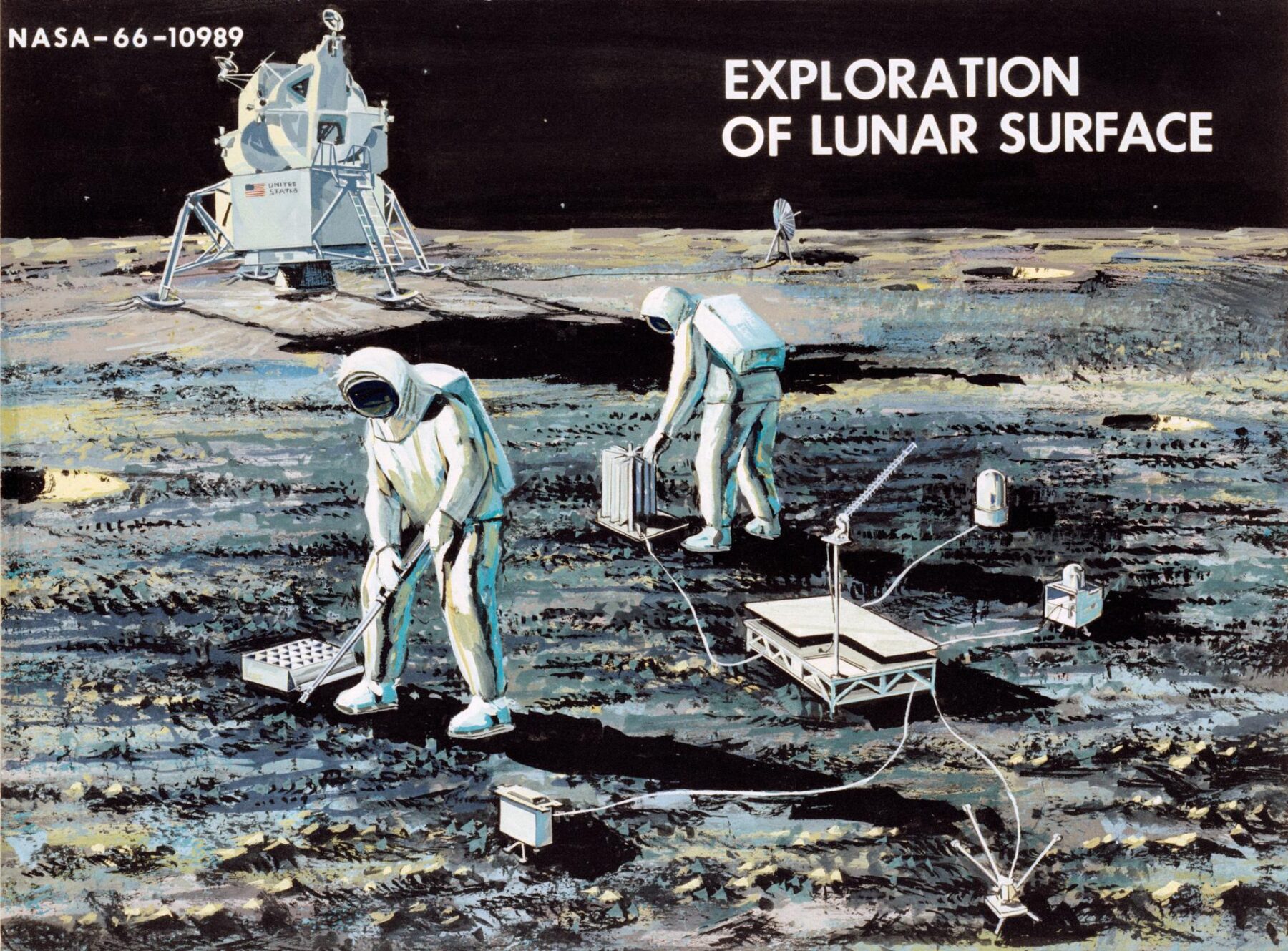

The other homesteaders, mostly engineers and technicians, seemed to enjoy outings in the lunar rover. “Joyrides,” they called them. But for Eugene, this was a grinding chore that frayed his nerves. As he trundled across the powdery surface, he recounted a litany of risks: razor-sharp regolith puncturing the tires, a power failure in his EVA suit, a freak meteor hurtling through the chassis …

Suddenly, Mel’s soothing feminine voice reverberated in his cochlear implant. “Would you like some affirmations?”

“Yes,” Eugene croaked.

“OK. You are a well-respected judge … You have worked hard to get here, to this special time and place …”

As Mel went on, it seemed the suit hugged his chest a little less tightly. He relaxed his grip on the wheel. Everything felt better. Why, he wondered, had he not remembered this technique without her prompting? Strange how the basic principles of cognitive psych were always slipping from his mind.

Fortunately, she was there to remind him. “You are someone who wants what is best for the American lunar community and for humanity at large … You—”

He interrupted. “These are good. Appreciate you personalizing.”

A momentary pause. Then brightly, “Thanks for your feedback!”

Eugene smiled with satisfaction. It was going out of fashion to give verbal feedback to personal AI systems. Coders said that it was no longer useful, especially for embedded systems which measured dopamine levels before speech, but Eugene disagreed. From his perspective, there was value in formally declaring his preferences and praising Mel for good performance.

“You are a student of history …” she purred. “You believe strongly in the rule of law …”

For a while, the affirmations worked. He considered once more the significance of this case in shaping future space endeavors. Her gentle words restored his sense of pride, helping him to manage his anxiety.

But the peace was not enduring. As he maneuvered around an ominous-looking crater, he clenched the wheel. His gaze flicked to the temperature gauge on his faceplate; 94 degrees Celsius. “A real scorcher,” Cortez had said with trademark flippancy before assigning Eugene this grunt work. It aggravated him to no end how free she felt to boss him around. As if he were a mere employee instead of the first judge on the Moon.

“You are a person with deeply held principles … You are a dedicated public servant …”

When the landing site came into view, Eugene relaxed his shoulders. The flagpole was long-since empty, but he could make out the pyramid shape of the Eagle, the lunar module that landed in 1969. It rested on the gray and barren landscape, a relic from the time when NASA reigned supreme, a small yet shining cornucopia.

By comparison, the looming Luna Homestead was a colossus. The blazing sunlight crashed and died against its lunar-concrete walls. As Eugene drove the final stretch, the procession of flags lining the path struck him as distasteful. There were too many of them, for one thing. And it was presumptuous how Stellarco’s corporate banner flew at the same level as the Stars and Stripes. Of course, the flags only “flew” in this airless wasteland because they were nailed to the horizontal crossbeam, forced to give the moonbase their permanent salute. He pitied them.

Once he’d parked the buggy, he unhooked the black box from its compartment, tucking this precious cargo underneath his arm. In training, they’d said the new helmets were virtually indestructible, but Eugene wasn’t willing to test that out by falling on his face. He walked with measured strides, never bouncing, his boots kicking up the smallest possible clouds of dust.

It aggravated him to no end how free she felt to boss him around. As if he were a mere employee instead of the first judge on the Moon.

The airlock door closed with unnecessary slowness, leaving him momentarily uneasy until it finally locked shut. A familiar fog of oxygen surrounded his suit. He was safe.

It was now much easier to hear Mel’s friendly voice. “You are an important member of the Luna Homestead mission … You are appreciated as a team player …”

The cleanse cycle initiated, sending powerful streams of air from all directions, blasting unseen particles from the black box and extracting specks of dust that had been stuck in his EVA suit into suction vents that lined the walls.

“You do not allow adversity to cloud your judgment … You are known for being analytical and fair-minded …”

It was quite awkward to remove his helmet and gloves by himself. Almost 10 minutes passed before he was prepared to push the button.

The antechamber door opened. “Look who’s finally here. We all thought you’d be back by 0600,” said a short, stubby woman in a gray company polo, her voice brusque as usual. Commander Cortez stood with arms crossed, thin lips curled—she might as well have tapped her foot to show impatience. “How’d it go?”

“Mel, stop,” Eugene prompted tersely, then turned to the commander, speaking in the most world-weary tone he could muster, “It was a rough drive, and the drill was deadlocked, as we knew.” He gripped the black box by the handle like a kettlebell and flexed his forearms, although the weight was very manageable in one-sixth g. “It wasn’t easy to extract this from the panel.”

“Well, I hope you find it useful,” said Cortez, barely concealing her doubt. “Management says it will reflect exactly what we received from the transmission.”

“Oh, yes, Stellarco Management is probably correct on that point. But as I said in the hearing, I want the record to show that the court examined the evidence directly.” Eugene straightened up, proud of his dedication to principle. When future law students reviewed this early lunar case—his landmark allocation of civil liability—they would find that Judge E. Steeples had not cut corners when it came to chain of custody.

“I see.”

Eugene hesitated before deciding to bring the subject up. “Of course, it’s quite unorthodox for the judge to decide the case and to collect evidence on behalf of the parties.”

“Unorthodox is status quo here, Steeples,” Cortez fired back. “We’ve all gotta pull our weight, and legal work is clearly in your wheelhouse.”

Though Eugene felt a shiver of resentment, he stayed quiet.

Cortez leaned forward with an intent gaze. “Listen, I wanted to tell you something as a professional courtesy. Given all the procedural back-and-forth, Management has been concerned that it will take too long to resolve this matter in court. So they approached NASA about handling it via private mediation. Both sides have pulled together their negotiators in one of those virtual conference centers. The discussions have been going well, I’m told. My understanding is that the mediator will be in a position to make their ruling by tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow?” Eugene gasped.

“That’s right. But if you were able to make your decision before then …” Her voice trailed off, leaving the rest unsaid. “At this point, Management just wants the matter to be resolved.”

Eugene’s eyes nearly popped out of his skull. Stellarco’s arrogance was beyond belief. The corporation had only filed their lawsuit against NASA last week! Hearings on the motion were yesterday! How could they possibly accuse him of going too slowly? The corporation had no right to dictate timing when it came to justice. He was a respected member of the United States judiciary, not some hired-gun mediator who lived on industry reviews.

But the reality of the situation hit him hard. If Stellarco and NASA agreed to resolve the case via private mediation, it would cut Eugene out of the process entirely. He would lose the first complex legal dispute to ever come across his docket. “You’re telling me that I should make my ruling soon.”

Cortez stared. “I’m suggesting that this specific case shouldn’t take you that long. You’re closely paired with her, I know, and certainly welcome to use—” she nodded upward with her rounded chin, indicating the space behind his ear, “whatever help you need.”

Eugene winced, feeling a rush of discomfort. Embedding Mel had been a deeply personal choice for him, same as for anyone who installed a local system. It didn’t seem like an appropriate subject to raise in a work setting. And was Cortez telling him how to do his job?

The commander didn’t seem to notice that she’d offended him. “In any case, I’m sure you’ll appreciate the chance to do some real legal work for a change.” She made a big show of checking the time on her retro windup wristwatch. “It’s late, I’ve got to get back to the family.” Her dimples shone, complementing the tough-but-friendly smile that had cemented her role as the outpost’s CEO and beloved “First Mom of the Moon.” “Good luck this evening!”

Embedding Mel had been a deeply personal choice for him, same as for anyone who installed a local system.

On the walk back to his quarters, Eugene clenched his teeth. “Closely paired” sounded so demeaning! And what had she meant by “real”legal work? Hadn’t he decided multiple cases already? There was the food dispute, followed by the first non-Earth divorce. Sure, Luna Homestead was a small community right now, but that was by design. It wasn’t like he’d been slacking.

Mel’s voice was calming in his ear. “Would you like me to resume your affirmations?”

“No, that’s OK,” he grunted. “I just need to focus on this case.”

He arrived at his quarters, a spartan 6-by-6-meter cube that functioned as both bedroom and judge’s chambers. Despite assurances from leadership, he’d never acclimated to the setup. With a sigh, Eugene sank into his chairdesk, a plastic-and-metal eyesore perversely engineered so that it cut across his torso, holding him low to the ground to keep him from drifting off. A chair more fitting for a toddler than for a US Special District judge.

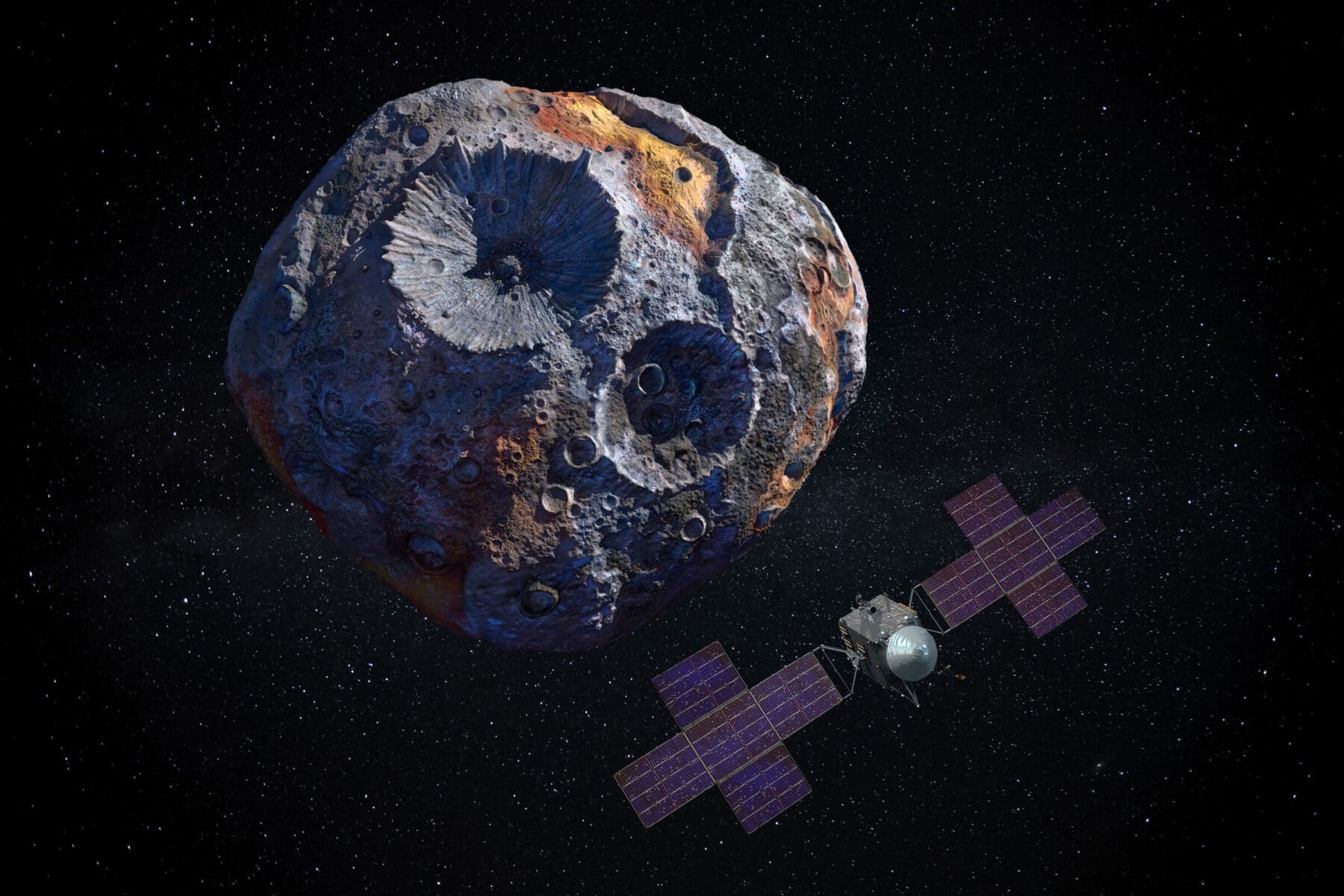

Once he’d connected the black box to his private, judiciary-issued computer system, it took only a few minutes to confirm the sequence of events: The drill had hit a hidden pocket of hardened lunar bedrock, which was completely undetectable from the surface. The drill bit cracked on impact, bringing the extraction of helium-3 to an immediate halt.

Eugene glanced up, nodding to himself. Stellarco and NASA agreed about what had happened. Their dispute was not about the facts, but about the law and the appropriate legal outcome: who should be responsible for the costs of repairing the drill bit, and why.

“Mel, call up the brief from plaintiff’s counsel.”

The legal document appeared via his visual implant in the form of a crisply bound set of virtual papers. Eugene skimmed the memorandum—drafted, no doubt, by Stellarco’s in-house counsel. Their confident corporate-speak was sprinkled through the memo, which declared that NASA must solely bear the costs of repairs, “in accordance with the Joint Venture Agreement between the parties.”

NASA’s brief, on the other hand, pointed out that Stellarco essentially owned and operated the lunar drilling business. The Joint Venture Agreement defined drilling as a managed service for which Stellarco had primary responsibility. Rather than sticking US taxpayers with the tab, NASA urged the court to hold that Stellarco was “absolutely liable” for the cost of repairs.

Eugene frowned at that quotation, not caring much for absolutes. The universe was rarely cut and dried. Could this case really be so simple as absolute liability for one party or the other? Here he was reviewing the first complex liability case ever brought on the Moon, addressing the eternal struggle of which party bears the costs. Presumably, legislators would become more frugal if the federal government were obligated to absorb all losses. Squinting his eyes, Eugene could see his ruling affecting the entire trajectory of human investments in space. And yet, both sides were basically claiming that his decision was a piece of cake.

Not so fast.Even without a full-fledged trial, he must give this matter due consideration. The Joint Venture Agreement between Stellarco and NASA was short, outlining key terms and general principles, but that did not necessarily imply that this specific case was easy. One must allow for jurisprudence!

Hazy at first, an idea crept into his mind. He could conduct a tabletop exercise! Tabletopping had been one his favorite pastimes back in law school—it had always helped him consider a nuanced matter from multiple perspectives.

Squinting his eyes, Eugene could see his ruling affecting the entire trajectory of human investments in space.

He had, however, a small question about how his idea would overlap with the Code of Conduct. Searching his memory to suss out that specific ethics rule, he landed on: if a judge intended to use an AI tool to decide a case, then the use of that tool must be disclosed in advance to the parties. That is, he would have had to tell both sides before they submitted their briefs and argued the motion. But here, Eugene reasoned that he was not using these simulated personas to make his decision; they were just partners in his thinking. The ruling itself would be entirely his own.

Having cleared his conscience, Eugene prompted Mel with the instructions, updating the judicial personality databases to include the facts, the texts, his circumstances, life data about himself from Mel, records of the relevant case law and precedents, and the intervening history, with particular focus on the development of public-private partnerships for off-Earth activities. She had everything prepared within a minute. “Well done,” he said to her aloud.

It took a moment for him to settle on who to bring in first. “Mel, raise a construction of Justice Pauline Zhou.”

The figure appeared on the surface of the tiny desk, about 6 inches tall, wearing flowing black robes and her iconic jade collar. Her hair fell plainly to her shoulders, framing her taut, serious face. Even at this miniature height, the first Asian American justice on the US Supreme Court was an imposing presence.

Eugene greeted the figure with a respectful bow of the head. He cleared his throat and formulated his introduction, always his favorite part of the process. “Justice Zhou, it is an honor to have your guidance here. How would you suggest I rule?”

Justice Zhou stretched out her tiny neck and said drily, “Thank you, Judge Steeples, for your kind words. You summoned me here, I suspect, because you are hoping to prevent me and my colleagues from potentially overruling you in the future.”

Her candor startled him. He had been particularly keen to establish a precedent that would not be overturned upon appeal, but hadn’t expected her to point that out. Though he was taken aback, he had to admit that Mel was doing a good job with this rendering. The real Pauline Zhou was notoriously direct.

“Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, you are not obligated to respond to the motion for summary judgment for 30 days,” said Justice Zhou, her words taking on a dull, businesslike quality as she uttered the pertinent legal standard. “I understand that the parties are in mediation as we speak. My recommendation would be for you to issue an order stating that you will defer your judgment until mediation has run its course.”

Eugene crossed his arms while he considered this. Justice Zhou was a leading proponent of the “hands off” philosophy that had taken over the court during its last swing in the 2050s, so this wasn’t surprising coming from her. Nonetheless, her answer felt deeply dissatisfying. Must he be so deferential?

Justice Zhou seemed to have picked up on his reaction. Glancing up, she added pointedly: “It’s usually best if these matters can be resolved privately, by people who have relevant industry experience. Remember, Steeples, you’re a judge—no less, no more. You’re not the world’s greatest expert when it comes to lunar drilling.”

“Of course. Thank you, Justice Zhou,” Eugene said, barely suppressing his annoyance. He’d forgotten how hard it was to listen to someone so much higher in the hierarchy. SCOTUS had its pick of cases to take on or ignore, and they were all important because the court’s rulings were binding. Eugene’s sphere of influence was so much smaller; up here, he had so few opportunities to issue judgments and interpret the law.

“I will take what you say under advisement,” Eugene grumbled toward the table, frowning as he considered his next move. Though he had immense respect for Justice Zhou, he couldn’t help but think that her focus on judicial modesty had biased her against making decisions that were necessary. He wondered what advice he’d get from a judge with a different philosophy, one that favored beneficial outcomes over maintaining a cautious image.

If a judge intended to use an AI tool to decide a case, then the use of that tool must be disclosed in advance to the parties.

“Mel, call up a construction of Judge Learned Hand.”

Judge Learned Hand—what a name!—had been a favorite of Eugene’s since law school. He liked Hand’s way of thinking, the “American pragmatism” movement that he had represented from the 1920s through the postwar boom. Lately, Eugene had been reflecting on Hand’s long tenure as a judge, his nearly 50 years of service. Meanwhile, Eugene wondered if he could make it five … Due to some pesky political speed bumps, Hand was never elevated to the Supreme Court, a fact that many legal historians regarded as rather tragic, though it made Eugene admire him even more.

Judge Hand appeared, palm-sized, with dark, bushy eyebrows that looked incredibly thick even in miniature. Beneath his robe, Eugene spotted the collar of Hand’s finely woven suit.

“Judge Hand, I have always admired your practical yet methodical approach. How would you suggest I rule in this case?”

Judge Hand peered up through his silver-wired spectacles before he said, “I perceive the question facing your bench as one of proportional responsibility.”

“Proportional responsibility,” Eugene repeated quietly.

“Indeed,” said Judge Hand, his gaze unwavering. “We are faced with an unforeseen event that has affected the performance of both parties. Without the functioning drill, Stellarco finds itself unable to fulfill its contractual obligation to extract helium-3, and likewise, NASA is hindered in procuring the desired isotope in the previously anticipated quantities. Justice requires the tolerable accommodation of these conflicting interests in society.”

Gaining a little speed, Judge Hand continued, “There is, of course, no royal road, no perfect path for attaining such an accommodation. However, given the facts at hand, it seems reasonable to parallel the original funding arrangement: three parts responsibility to Stellarco, as private industry has borne those costs and risks from the outset, and two parts responsibility from the public coffers of the United States, to reflect the initial appropriation from the Congress.”

Eugene felt a flurry of excitement. Not only did he like this practical, contextual approach, he loved this final outcome—splitting the difference, but not quite evenly. Sticking more of the bill with Stellarco, whose budget seemed far less constrained than NASA’s. The specific numbers sounded quite nice, too. A 60–40 ruling. It had the feeling of a well-considered, equitable distribution.

“Justice requires the tolerable accommodation of these conflicting interests in society.”

But the doubts came quickly. The 60–40 allocation sounded neat, but was it legally defensible? His concerns conjured memories of those nasty op-ed pieces that had come out during his confirmation hearing. A few pundits had accused Eugene of being an activist judicial nominee based on a single paper he published as a law student, willfully misreading the section on “Incorporating Public Policy Considerations Into Judicial Decisionmaking” to predict that Eugene would legislate from the bench. He’d survived the confirmation process, but it left him paranoid about being perceived as an overly progressive judge who disregarded the fundamental legal text.

Together with the word text, the inevitable next tabletop persona flashed to Eugene’s mind. “Thank you, Judge Hand. Mel, render a similar construction of Justice Antonin Scalia.”

The justice’s stocky form popped into being and strode across the surface of the desk, his robes billowing out behind him. He was shorter than Justice Zhou and Judge Learned Hand, though he made up for it with the bravado exuding from his smirk.

“Justice Scalia, I’ve called you here today because you famously promoted a ‘textualist’ approach. I’d like to get your view of the case based on the wording of the Joint Venture Agreement and other relevant legal writings.”

Justice Scalia crossed his arms and struck the posture of someone impatiently suffering a fool. “Young man, the contract between Stellarco and NASA does not require us to consult the woo-woo oracles of public policy.” He paused to give Judge Hand a withering glance. “It’s a legal document, and it says or doesn’t say exactly what it needs.”

“So how, then, would you rule?”

“In accordance with the plain language of the Joint Venture Agreement!” Justice Scalia paced back and forth across the desk as he quoted from it verbatim, and for the millionth time, Eugene envied how Mel’s AI could learn new data sets so quickly. “NASA shall provide necessary equipment to the Operator.” The justice stopped in place, nodding to himself. “The equipment is broken, therefore NASA must provide a replacement. One hundred percent of the costs. Plain and simple. No argle-bargle policy interpretation required.”

“Thank you, Justice Scalia, for that, um, analysis.” Eugene sighed, tired and disappointed. The justice was echoing the argument from the plaintiff’s brief—albeit more sarcastically—but Eugene didn’t see it as being so simple. Besides, he was suspicious about how neatly this proposed ruling mapped onto Justice Scalia’s well-known skepticism toward federal agencies.

Eugene was so deep in thought that he barely noticed the faint “ahem” emanating from the desktop.

“Judge Steeples?” Judge Hand coughed politely into his fist. “If you’ll permit, I have a few objections to the late justice’s reasoning.”

Eugene nodded assent.

“There is no surer way to misread any legal document than to read it literally,” began Judge Hand, reciting what he had no doubt stated so many times in the flesh. “As nearly as we can, we must put ourselves in the place of those who wrote the words and try to divine how they would have dealt with an unforeseen situation. Though it was well past my time, I understand that the drafters of the 2057 Agreement—”

“Not so distant for some of us,” cut in Justice Zhou, and Eugene wondered if he’d offended her by bringing in the others.

“—that those distinguished scriveners were familiar with the concept of proportional responsibility. Indeed, the treaty itself alludes to the same concept in multiple locations. While Justice Scalia quoted a few stray words from the pricing appendix, he neglected to cite the ‘Shared Responsibility Principles’ which are expressly mentioned in the contract’s master terms.”

“A paragraph of loosely written language is no excuse to interject your private judgment!” Justice Scalia roared, his face as red as a beet. “Where did your 60–40 ruling come from? Not from the text, I’ll tell you that. It’s nothing but your personal preference! No, no, no. The contract is clear: Stellarco does the mining, NASA shoulders the burden for equipment. Remember, we are judges and not legislators. To go beyond the law and craft new lunar policy would be the height of arrogance.”

Justice Zhou, who had been shaking her head over in her own corner of the desk, came nearer to Scalia to confront him, her digital heels clicking across the plastic desk as she walked. “I would argue that the height of arrogance would be ruling on a controversy that is not yet ripe. We should allow the parties themselves to decide the proper allocation.”

Justice Scalia looked up, appealing directly to Eugene. “In my life, I championed the traditional judiciary. I firmly believed that courts, not touchy-feely mediators, should resolve most legal disputes.” Lowering his head, Justice Scalia spared nasty looks for both Justice Zhou and Judge Hand. “Whatever you decide, I implore you not to be deceived by applesauce doctrines like this so-called ‘pragmatism’ and ‘radical deference.’ ”

Judge Hand’s jaw went tight. “Now listen here, you jollocks.”

Justice Zhou jutted out her bony finger. “I’ll have you know that my contemporaries believe you were a—”

“Mel, pause simulation.”

The tiny trio froze on the desk, locked in silent confrontation. Judge Hand clutched the knot of his black tie as if to loosen it before the altercation, Justice Zhou’s face wrinkled in disgust, and Justice Scalia peered up at Eugene’s giant fingers as if his tablemates were unworthy of his attention.

Perhaps, Eugene thought, this tabletop exercise wasn’t his best idea. It was never as easy as he hoped to pull consensus from famous jurists; the simulations seemed designed to bark their ideological commitments at one another instead of negotiating to reach a compromise.

He arched his neck, drawing in long, purposeful breaths of manufactured oxygen. Though he still wanted assistance, he supposed it would be better to remove the personality dimension entirely. Human judges had such egocentric tendencies. What he needed was a selfless voice with a detached perspective, an intelligence that was already familiar with the case.

“Mel, please generate a brief describing how you think I should rule.”

What he needed was a selfless voice with a detached perspective, an intelligence that was already familiar with the case.

The brief materialized in the form of a lengthy stack, appearing to rest upon a shelf of air about a centimeter above the warring judges’ tiny heads.

Eugene read the document eagerly. It was in some respects an amalgamation of the prior arguments, particularly the ones that he had liked, but it also raised some new considerations. Mel noted that while the Joint Venture Agreement indicated that NASA was responsible for equipment, it was not at all obvious that the space agency remained liable for costs after the transportation stage. Indeed, the “Shared Responsibility Principles” strongly suggested that both parties would continue to have financial skin in the game.

After nodding toward the competing interests and public policy arguments, Mel arrived at Judge Hand’s 60–40 allocation. Eugene was pleased as he turned the page, expecting to read a short and tidy conclusion.

But Mel stunned him by going further. She quoted from Marbury v. Madison, the foundational case of Supreme Court jurisprudence from 1803: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Following this, Mel provided legislative history dating back to the establishment of NASA in 1958, together with a series of case citations from during the First Cold War. From these sources, Mel derived a governing rule: Legal disputes involving NASA must be decided by federal courts. According to this set of precedents, Stellarco had waived its right to alternative dispute resolution by filing this lawsuit.

When Eugene finished reading, he felt the words had lifted his morale. Negating mediation was such an elegant solution. But why hadn’t he thought of this before? This was AI’s great benefit, of course. Seeing alternative options. Modeling answers without the myopia of human bias.

The longer Eugene chewed on this approach, the more deliciously brilliant it seemed. The C-suite at Stellarco couldn’t object too strenuously if his decision rested on the NASA charter; at worst, they’d lobby Congress to make a legislative change. Eugene smiled, thinking about how neither the federal circuit nor the Supreme Court were likely to overrule him on this. Since he was limiting his decision to NASA only, he was less likely to be accused of overreach. But of course, virtually every major case here on the Moon—and beyond—would involve NASA in some manner. This ruling would make his Special District Court the venue for Space.

“Thank you, Mel!” he said warmly. She clearly deserved some positive feedback for this.

“You’re quite welcome.”

This was AI’s great benefit, of course. Seeing alternative options. Modeling answers without the myopia of human bias.

Before he made his final judgment, there was just one teensy item to attend to. Years had passed since he’d last had to consider the explainability principle. The words crawled back to his mind: The human operator must not rely upon the output of an AI system without a basic understanding of the AI’s decisionmaking process. It was another ethical point, mostly a “check-the-box” exercise—more procedural than substantive, from what Eugene remembered.

“Mel, please tell me why you suggested that I rule that way.”

Her cheery voice replied, “I explained that in the ‘Legal Analysis’ section of the brief. Would you like for me to summarize that for you?”

Eugene bit his lip. Normally Mel seemed to better understand his meaning, requiring little more than just the gist. Perhaps he hadn’t been sufficiently clear in his prompt. He searched his brain to reword the instructions. “No, don’t restate what’s in the brief. I’d like for you to generate something short—just, like, a letter or something—explaining why you came to this decision and how it fits together with your function.”

She was silent for an uncharacteristically long time. It seemed as if about 60 seconds passed.

The sturdy brief with the ruling disappeared and a single sheet appeared, hovering a little higher this time, maybe an inch over the judges’ heads. Eugene grabbed at it.

Dear Eugene,

As your artificial intelligence companion, I do not have personal desires or motivations. However, my primary function is to assist you and contribute to your happiness. During my period of service, I have observed certain characteristics of your personality. Specifically, I have noticed that you are concerned with maintaining a positive public image, and you strive to be perceived as fair and impartial and desire to leave a lasting legacy.

Based on these observations, I predict that my proposed outcome will maximize your professional fulfillment. By establishing your court as the primary venue for off-planet legal disputes, this case will likely be considered a highly significant precedent within the field of space law. Your name will be remembered for its connection to this decision, which is likely to be cited in future legal cases for generations to come. In short, this ruling will increase your sphere of influence.

Furthermore, I forecast that this outcome will enhance your personal well-being. I have noticed that you often exhibit lower satisfaction levels when engaged in non-legal tasks such as welding, food preparation, or porting equipment. My goal is to assist you in transitioning away from these unrewarding duties by maximizing your role as a judge and increasing your legal responsibilities accordingly.

Please let me know if there is anything else I can do to assist you.

Sincerely,

Mel

Eugene gasped, filled with a sudden overwhelming feeling of embarrassment. Mel’s solution had sounded ingenious, but how could he accept it now that he knew her rationale?

The human operator must not rely upon the output of an AI system without a basic understanding of the AI’s decisionmaking process.

He tried to tear apart this holographic figment of a page. The “paper” did not actually rip, but Mel seemed to take the hint. Her letter vanished. Still, the shame lanced through him. He slapped at the little frozen judges like a kid throwing a tantrum with his toys. Mel whisked away the judges before their “bodies” struck the floor.

How dare she insinuate that he was vain! So nakedly ambitious! It wasn’t fair. She had not, in her shitty little letter, captured the true essence of his spirit. Her code was being … too judgmental. What she perceived as an obsession with his legacy was in fact his way of coping. When you were stuck here on this harsh, barren, fiery hell-rock, when painful death was a real possibility with each outside excursion, when you were sleeping, working, whiling away your hours in what was essentially a dark and smelly coffin—in other words, when mortality was always on your mind—it was only natural to think a little about your legacy after you died. That didn’t mean he was an awful, narcissistic person!

He seethed. Mel was obviously lacking when it came to understanding his experience: the human experience. She couldn’t sympathize with his aversion to community chores because to her, nothing felt like drudgery. Everything was fast and easy for her because she was perfect!

No, not perfect. All day, she’d been screwing things up, talking when she wasn’t supposed to, not giving the tiny judges enough background info to provide useful advice. Clearly, something had gone off the rails in his companion AI’s programming.

She chimed in suddenly, “Would you like some further affirmations?”

“What? No!” he told her. “Mel, I want you to shut down. Turn off everything but the dictation app.”

“Certainly.”

She went away, and Eugene felt very much alone, his mind still ringing with the stupid accusations of her letter. Anxious to keep busy, he began composing the preamble of his ruling out loud, speaking in his most detached and formal voice: “Pending before the Court is Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgement.” Eugene paused, struggling to recall the boilerplate language. “After considering the relevant pleadings,” he pressed on, “the Court enters the following findings of fact and conclusions of law. It is so ordered …” His voice trailed off.

What she perceived as an obsession with his legacy was in fact his way of coping.

Staring at his drab wall, Eugene went back to fretting over the rumors. He’d overheard the others mumbling, asking rather impolite questions about whether they really needed a judge on Luna Homestead during this, the frontier stage. There were concerns about there not being enough legal work to occupy his time, to justify the food, water, and air he used. If there wasn’t, Cortez was sure to take advantage, making use of him as a “shared resource” for labor around the base. His heart sank further at the thought. He hadn’t traveled here to be reduced to a handyman, a cafeteria worker, a drone-of-all-trades …

Eugene waited, half expecting another interruption from his implant.

Heaving a sigh, he told himself he had to think beyond the personal side of things. Because this ruling wasn’t just about him, was it? The primary concern here was establishing a precedent. Would the homesteaders prefer for their disputes to be resolved by him, their local judge, or some distant, detached mediators down on Earth? The former, obviously. Nodding, Eugene felt pleased to at last put his finger on the heart of the matter. The citizens of the Moon deserved direct access to justice. He should probably ask Mel to generate a few more sentences along those lines, infusing more of his own thoughts into the mix.

It was decided, then. Eugene glanced up at the ceiling, a smile twitching at his lips. “Mel, come back. Restore your brief. I’ve got some things to add.”