Carberry leaned back on a stool at Doyle’s and admired the coffered ceiling. It was rare to see that kind of handiwork anymore. People were so beguiled by the data streaming through their AR rigs that they didn’t appreciate real craftsmanship. The world probably was more entertaining through a pair of those lenses that transformed the city into a digital canvas: rose-colored pterodactyls swooped past the glass facade of the Hancock Tower and neon green sea serpents snaked around the boats ferrying commuters across Boston Harbor. Weather reports appeared on one side of the Prudential and stock prices ran down the other. But Carberry preferred his reality handcrafted and hardwired, and at Doyle’s the booths were made of wood and the beer was fresh. The barkeep pulled a pint of ale from the cask and set it on the bar. Carberry drank and gave thanks that they didn’t allow those damned lenses in the pub. When his pager buzzed, he wanted to dunk it in his beer.

The pavement in front of the residential tower at Arbella University was awash in red and blue lights by the time he pulled up, and a sergeant was scanning the scene through a popular new AR rig. He paused and held up a bag of weed, but Carberry gestured with his chin toward a square-jawed Latina with pigtails who ducked under the police tape wearing a custom headset and a backpack that looked heavy for her small frame. “I’m up again?” she said.

“Who paged whom, Gabi?” he said.

Detective Gabriella Jimenez examined the bag. “It fell out of the sky right after she did,” the sergeant said, pointing to an open window high above the pavement. Jimenez glanced at Carberry through her violet lenses. “She?” The sergeant fumbled with the toggle on his headset and scanned the broken remains of a coed in the middle of the street, eyes turned toward heaven, a look of disbelief on her face. “Rachel Townsend, freshman,” he said. “She’s a local. Grew up in Wellesley. Majoring in digital arts with a minor in performance.”

Carberry turned away from the officer. “Are you not seeing what I’m not seeing?”

Jimenez flipped up the lenses on her headset. “Definitely not.”

“Sergeant, let’s go see what Rachel was doing before she wound up out here,” Carberry said. “What’s the room number?” The sergeant fidgeted with the toggle on his glasses again. “Is everybody wearing those things now?” Carberry said.

“I’m just getting used to them,” the sergeant said. “ARkade did a drone drop on campus this morning.”

“They’ve been littering the city all week,” said Jimenez, shrugging off the backpack and stretching her neck.

“You’ll have to excuse my partner,” Carberry said. “She has refined tastes in tech. Builds her own.”

A small drone emerged from Jimenez’s pack and began orbiting the scene, gently rising with every pass.

Room 647 looked like a museum exhibit of dorm-room chaos curated by experienced teenagers. Nacho chips spilled over a huge wooden cable spool that served as a table. There was a Metallica poster on one wall and a poster of Jay-Z on another. A pile of dirty socks and shorts had been pushed into a corner before the guests arrived.

“You smell that?” Jimenez said.

“The socks or the weed?”

“The weed,” she said. “I grew up with three brothers. I can’t even smell the socks.” She picked up a bong and scanned the charred contents of the bowl. It was the same as the weed in the bag that went out the window. “The kids pair this stuff with some of the over-the-top AR experiences when they want to have a big night in.”

“Tossed the weed but forgot the pipe—not a valedictorian,” Carberry said. “Am I right, officer, or are we standing in the room of a future Fulbright scholar?”

“Jason McAfee,” the sergeant said, focusing on his lenses. “He’s a floor leader, responsible for looking after the younger students.”

“What have we here?” Jimenez picked up a new pair of ARkades from the floor by the window. Her drone entered through the open window and began to orbit the room. “Listen, Carberry,” she said, quietly so the sergeant wouldn’t hear. “Thanks for answering my page tonight. I appreciate the help.”

He picked up a bowl from the overturned cable spool and offered it to her. “Chip?”

She rolled her eyes and decided to save her questions for later. The drone returned to her side and hovered at waist height. Jimenez established a laser connection between the AR glasses and the drone, which synched what it had learned orbiting the space with what was stored in the ARkade rig. A scale version of the room appeared in the air in front of Jimenez and Carberry; pulsing music preceded a digital apparition of six college students at play. A young man took a deep pull on the bong and exhaled; the ARkade rig morphed the twisting line of smoke into a floating parade of circus animals. The students giggled as tie-dyed elephants, giraffes, and zebras cavorted to the loping rhythm of Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind,” the slick production making the song’s grit-to-glory theme work for these children of privilege dancing with the smoke. Jason McAfee was the guy with the bong. Rachel Townsend was sitting on the other side of the improvised cocktail table, listening and laughing, but somehow apart as the smoke and the boxed wine knitted the others together in mirth. The gaze of the lenses shifted from Jason to the psychedelic circus animals parading through the air, to Rachel, and back to the host. A glassine chime cut through the moment and Rachel sprang out of her seat. “My friend is downstairs,” she said, pausing at the door to smile at Jason. “Could you open that window?” she said. “It’s stuffy in here.”

Jason seemed nonplussed when he came back to the table. “She didn’t say anything about a friend,” he said.

“It’s probably just her roommate,” said the guy wearing the ARkades. “Don’t sweat it. She likes you, I can tell.”

“I hope you’re right, Keating,” Jason said. “I didn’t set this night up for nothing.”

“The kids pair this stuff with some of the over-the-top AR experiences when they want to have a big night in.”

The bong made another pass around the table and Jason filled his guests’ cups with boxed wine. Keating took the bong and blew a thin stream of smoke into the air: a purple tiger with black stripes leapt up and raced across the ceiling with a roar, provoking an explosion of giggles that cascaded into the music. “Play it again!” a girl reaching for the bong implored nobody in particular, her gaze lost inside her lenses, her head swaying back and forth to the beat. “Play it on repeat!”

Everything in the room was a little hazy when Rachel came back.

“My friend is here!” she declared. A slender young Black man with a buzz cut and a thin gold chain entered behind her. Keating looked at Jason and back at the newcomer. The smoke from the synthetic weed was creating a lot of visual noise in the replay, but Carberry could see the kid’s smile vanish when he registered the eyes on him. He offered the group a slow nod.

“Hi Rachel’s friend!” the girl with the bong called out, and then she went back to dancing to the music. The boys sat around the table drinking and saying very little. Rachel and the newcomer nestled together in the corner on the wide sill by the window overlooking the Charles, the city lights glowing below. Rachel breathed the evening air through the open window, and then she pulled the young man close.

Jason looked at his friend, who looked at his watch. “I’ve got to bolt,” Keating said. “Looks like you don’t need me tonight anyway.”

“Yeah, thanks to that guy,” Jason said.

“I’d wrap it up if I were you,” Keating said. “It’s your place. Clear the room and head out, restart your night.”

“I should,” Jason said, lurching toward the couple in the corner. “I should fucking …”

“Jason!” Keating grabbed his shoulder; Jason lunged forward, and the two of them stumbled toward Rachel and her friend. Keating’s ARkade rig clattered to the floor and the video image went black for a beat. When it returned, Jimenez and Carberry were looking up at Rachel’s friend from the spot where the lenses landed on the floor. He was staring out the window, eyes wide, mouth agape in a silent scream. Rachel was gone.

The music stopped. A girl whimpered. “What happened?” Jason said.

Rachel’s friend looked at all the faces looking back at him and bolted for the door.

“What happened?” Jason yelled. The girl started screaming.

Jimenez shut down the replay. “Well,” she said. “I guess we know who to talk to next.”

Keating’s ARkade rig clattered to the floor and the video image went black for a beat.

Carberry looked at his watch and yawned. “It’s dinner time for me,” he said. “Let me know if you find the kid.” Jimenez put her hands on her hips, but as Carberry opened the door to leave, the sergeant spotted the red plastic cup on the windowsill. “Looks like that’s where our victim took her last drink,” he said.

“It’s probably time to clue the sergeant in,” Carberry said.

Jimenez beckoned him to the window. The sergeant looked down to see the crumpled body on the pavement, his fellow officers holding back a group of gawkers. “Take off your lenses and look again,” Jimenez said.

There was no body in the street. “What the fuck?” he said.

“That’s what we’d like to know.”

Carberry stopped at the Taiwan Café on his way home, and the smell of minced pork sizzling in soy sauce wafted him back to the last time he had dined there with his wife. It was Maggie’s favorite place in Chinatown. When they could find a babysitter, they would drive into the city and sit at the small table in the back. She ordered the wonton soup and ginger chicken in lettuce wraps that night, and he asked for the minced pork and the dumplings. They laughed about little things, they giggled about whatever Molly had said to Richie at the beach that morning. He could hear the children’s voices as Maggie described their day, he could see their eyes shining in the sunlight as the Atlantic surf washed up around their knees. After dinner, they would ride the Red Line to Harvard Square to catch whatever was playing at the Brattle. Carberry thought of how Maggie gripped his arm watching Key Largo as the hurricane bore down on the hotel, with the corrupt and broken people sheltering inside and the locals left out in the storm to fend for themselves.

Carberry finished his meal without tasting it, and paid the check without realizing it, lost in a maze of memory, listening to voices echoing along the darkened corridors of the past. And then he was drinking again, or at least that’s what it felt like must have happened when he woke up on the couch in the old Victorian where he lived now in Dorchester. His eyes were heavy and his brain was dry, and there was a toxic mass that his belly wanted to expel. His ’72 Chevelle was not in the driveway. Doyle’s, he realized, pressing the heels of his palms into his eyes. Gabi must have picked him up and driven him home. Again.

Jimenez brought his car back after the morning roll call and slid over to let him drive. Carberry liked to ride along the Jamaicaway at the start of the day, the throaty V-8 resonating over the hum of all the electric cars on the road. “So, did Jason McAfee wake up behind bars this morning?” he said.

“Yes, but I don’t know how long he’ll stay there,” she said. “He’s freaked out. Still thinks the girl went out the window. If he was in on it, he’s a great actor.” Carberry kept his eyes on the road. “But there’s a problem,” she said. “The girl still hasn’t turned up.”

“You told the sergeant to keep it to himself?”

“Yeah, he’s playing along.”

“And the other kids?”

“Didn’t see what happened. They were watching Keating tackle Jason, and then the girl was gone,” she said. “But they all have a theory.”

“Oh, let me guess …”

“Yeah,” she said, “the Black kid did it.”

“Great. Now it’s officially a shit show.”

Carberry rounded the rotary and drove along the Arborway. Jimenez trained her glasses on the trees in the Arboretum. “The sap is rising early this year.”

“You can tell that by looking at them?”

“Image of the tree linked to the Olmstead website. They’re tracking the maples already.”

“I was almost impressed.”

“Don’t knock it till you try it, Carberry,” she said. “I could build you a quality rig.”

“I’d sooner wear a bandana over my eyes.”

“These are the real world, only better,” she said. “At least I’m not wasting my time in one of those VR warehouses.”

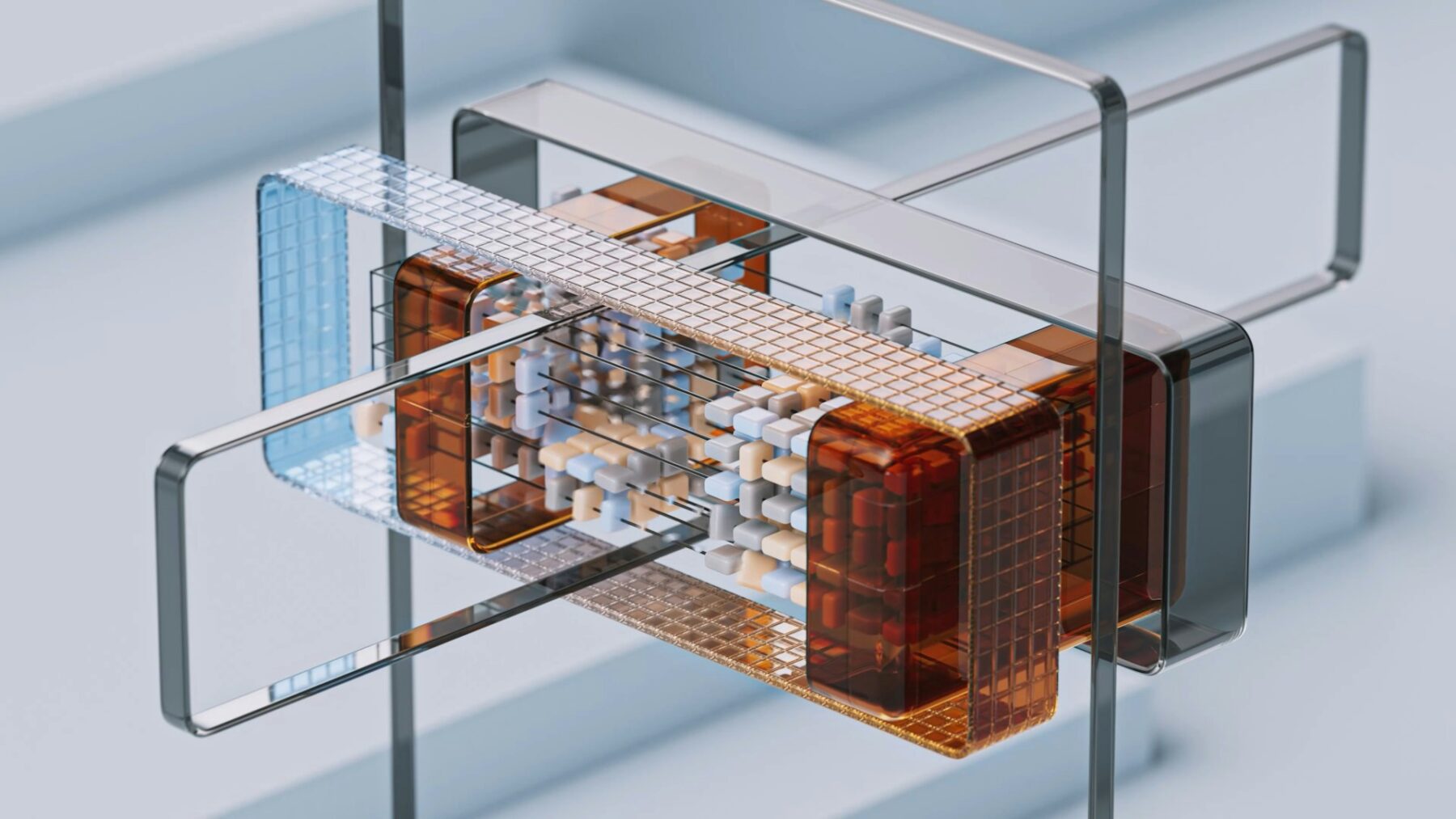

He couldn’t argue with that. They were living in a time between brick-and-mortar buildings and structures spun out of carbon and light that spiraled into the sky; between an age of reason and an era of mysticism coded in ones and zeroes that could erect castles in the clouds and make whales fly. The metaverse had been choked off by snow-crash fears and sad tales of virtual reality addiction. People were put off by the tangle of cables and the bulky headsets and the haptic gloves that made it impossible to hold a beer. VR enthusiasts wanted to soar like energy sailors, not clank around like medieval knights errant in some technovillage. When Moore’s Law failed to yield sufficiently powerful lightweight home sets, would-be VR tycoons shifted their bets to themed installations that allowed users to experience brand-appropriate wonders of the metaverse without the need for any personal gear—full-immersion environments outfitted with massive microcamera arrays and composite holoscreens that could place you on a mesa in the desert Southwest or square you up against Bird at the Garden, and haptic mist systems so carefully calibrated that you could feel each strand as your fingers brushed through the hair of your celebrity crush. But those next-gen meta-environments required so much space and so much computing power that only the ludicrously rich could afford to install one at home; for most people, state-of-the-art VR was always someplace else, either the office park or one of the VR depots the industry installed in abandoned multiplexes or bankrupt department stores.

At first, the public formed long lines to enter those new zones of fantasy where they could experience gladiatorial contests from ancient Rome or full-contact action from past Super Bowls; intimate moments with idealized entities, magic, art, or simple mayhem. But fads fade, and leaving the house and standing in line was a hassle. Most VR depots today looked as lonely as an adult bookstore by a highway truck stop. The saddest users were the nostalgia junkies—people who sought out calming visions of the past at their local depots, sliding their paycards to buy an hour of a better before, a favorite meal with a beloved someone, another ride on a father’s motorboat, or just a biomechanical handjob from the coed they never worked up the courage to proposition in college.

They were living in a time between brick-and-mortar buildings and structures spun out of carbon and light that spiraled into the sky.

AR was a different story. The lighter, more flexible tech claimed to enrich everyday life in ways that VR never pretended that it could. While the megacorps were competing in the VR market, dozens of boutique products blossomed across the augmented reality landscape. Life became more entertaining for the masses: dinner parties were twisted like balloon animals through the lenses guests wore, transforming a casual evening into a black-tie rave with Tolkien’s bearded dwarves serving hot courses from silver salvers. Revelers took turns disguising other guests in shimmering costumes of their choosing, or wrapping them into animated skits selected from a reel of themes provided by the hostess.

“Anything come up in this morning’s briefing?” Carberry said.

“The city is losing its mind,” she said. “There was a run on a bank in East Boston that isn’t having any kind of financial problems, and a SWAT raid reported in Charlestown.”

“What’s unusual about a SWAT raid in Charlestown?”

“Nobody knows who it was—not us, not the staties, not the FBI.” Jimenez decided it was time to say what was on her mind. “Why don’t you come back to the station and start seeing the briefings yourself?”

“Why would I want to do that?”

“You’ve been coming around and dipping back into cases. You’re still answering that antique buzzer in your pocket,” she said. “It’s like you’re here but you’re not fully back. I don’t think you’re fully anywhere half the time. You’ve been in limbo for too long.”

“Maybe limbo is where I belong,” he said.

The same sergeant was waiting by a bank of video screens in the Arbella residence hall basement. Jimenez and Carberry sat down and a video tech took his cue from the sergeant. A young woman with red curls and a short dress and black boots appeared on screen. “Rachel Townsend in the lobby,” the sergeant said, “moments before her death.”

“It’s like you’re here but you’re not fully back. I don’t think you’re fully anywhere half the time. You’ve been in limbo for too long.”

“So there was a girl,” Carberry muttered. A celluloid moment later, a young Black man with a black Sox cap pulled low over his eyes entered through the revolving door. “And a guy,” Jimenez said.

“Wait, there’s more,” the sergeant said.

Rachel and the young man embraced, and she held the embrace a little tighter and a beat or two longer than you would have expected if she had been just greeting a friend.

“Nobody greets me like that,” Carberry said.

“Can we get a look at his face?” Jimenez said.

“The hat blocked his face from all of the lobby cameras,” the tech said.

“But do not despair detectives,” the sergeant said, turning to the tech. “Let’s jump ahead.”

Footage from a camera in the elevator appeared on the next screen. Rachel pushed her friend playfully up against the wall and kissed him. She pressed her hand firmly against the zipper of his blue jeans and he pulled her body against his. Sliding her hands up his chest, she held his head and kissed him again, knocking his cap to the ground. He looked up briefly and laughed before he picked it up from the floor.

“That does not look like one of our students,” said a nasal voice from behind. Carberry turned to see a skinny man with a buzz cut wearing wire-rimmed glasses and an argyle vest. “Is that your suspect?”

The sergeant introduced Bob Acheson, dean of students, to the detectives. Carberry remained seated. Jimenez didn’t offer to shake his hand. “For all we know right now,” she said, “what happened to Rachel Townsend was a tragic accident.”

“I’ve just come from meeting with Rachel’s parents,” the dean said. “They don’t believe this could have been an accident.”

“Shit,” Jimenez muttered to Carberry. “The parents.”

“The mother was a mess,” Acheson said. “She was clutching this ragged stuffed rabbit, and she was talking about ballet lessons and soccer. But the father was another matter. He is not a man to be trifled with.”

“How’s that?” Jimenez asked.

“Philip Townsend,” Acheson said.

“ARkade Development?” Carberry said. “That Philip Townsend?”

“One and the same.” Acheson said.

Carberry turned into a driveway that wound through a grove of maples and ended in a cul-de-sac in front of a tall blue Victorian with white trim around the doors and windows. The stone path to the porch was lined with morning glories and Queen Anne’s lace, and a wide green lawn ran down a gentle slope toward the trees. “You’re on point,” he said.

“Why me?” Jimenez said.

“I don’t do grieving parents anymore.”

Anne Townsend answered the door in a black linen frock with her hair pulled back in a bun. Philip Townsend was waiting in the parlor.

“Gabriella Jimenez, sir,” she said, removing her sunglasses. “And this is my partner, Detective Carberry. We’re very sorry to be meeting you under these circumstances.”

“Detectives,” he said, gesturing toward a leather sofa. He was tall, with a sharp chin and thinning blond hair arranged neatly across his scalp.

“I’d really like to know more about Rachel,” Jimenez said.

Mrs. Townsend picked up a framed photograph from the coffee table, a high school graduation portrait of a smiling girl with bright red curls spilling over her shoulders. Rachel was a soccer star, and she loved the theater, her mother said. “But Phil wanted her to work at the company.”

“Really?” Carberry said. “Did she work at ARkade during high school?”

“Yes,” the mother said. “Phil let her intern in the research lab during the summers, but her heart was really in the theater.”

“Look, I don’t know why we’re talking about Rachel,” the father said. “I’d rather hear what you know about that boy Bob Acheson just called me about. Do you have the video?”

“Mr. Townsend, we don’t have any evidence that—”

“From what Bob told me, it seems pretty clear. Rachel was lured up to that room by some older boys, and one of them got her alone in the corner. Maybe he was drunk, maybe he was high, maybe he’s just some fucking animal.”

“Philip!” Mrs. Townsend said.

“I don’t know if she resisted,” he said, “maybe he got angry.”

“And what were those other kids doing, just sitting there?” the mother said. “Didn’t they hear her? Why didn’t they help her?”

“When will we be able to see our girl?” Mr. Townsend demanded. “Acheson said we had to go through you.”

Jimenez held up her hand. “Mr. Townsend, Mrs. Townsend, please,” she said. “Rachel didn’t go out that window. It was some kind of hoax.”

“A hoax?” Mr. Townsend was astonished. “That she fell six stories?”

“It had something to do with the glasses.”

Mr. Townsend stood with his mouth open for a moment, and then he finally sat down next to his wife.

“I don’t understand,” Mrs. Townsend said.

“Anybody who was wearing a pair of the new ARkades saw her lying in the middle of Commonwealth Avenue,” Jimenez said. “But when we showed up, there was no body there.”

Philip Townsend rubbed his brow. “Where is she now?”

Jimenez tried to think of something comforting to say. “Nobody heard anything alarming,” she said. “I’ve spoken to all of the other students in the room and nobody saw her in any kind of distress.”

“All of the students,” Mr. Townsend said. “That boy wasn’t a student, was he?”

“It seems that he was a friend of hers,” she said.

Philip Townsend scoffed. “What makes you say that?”

“What exactly did Dean Acheson tell you about that video?”

Carberry awoke with a splitting headache on Sunday morning and looked out the kitchen window to confirm his car wasn’t there. He initiated hangover protocol: two soft-boiled eggs on toast and a cup of strong dark coffee, followed by an eight-ounce glass of Gatorade and three maximum-strength Tylenol. Once the caffeine restored basic mental function, he showered and changed for Mass. He took a meandering walk to clear his head, and everywhere he turned he encountered clusters of people wearing the new red and green ARkade glasses. Some were hunting for fantastic figures hidden at coordinates that mapped the digital world to the parks and pavement of Boston’s neighborhoods, others were taking historic walking tours that taught citizens about the city’s role in forging an enduring democracy. Others, he gleaned from passing comments, were visiting sites of notorious crimes, and soon the path to St. Mark’s started to seem like a trek through his career. What a tour he could lead: on the top floor of that three-decker on Dorchester Avenue they found the body of the Widow Johnson, who had been strangled by the mistress of the husband whom Mrs. Johnson had stabbed to death after discovering he was having an affair. That bench in Franklin Park? That’s where Shondra Samson was sitting when a punk from the Blue Hill crew rushed by with guns blazing, missing everyone he had been aiming at but killing the 11-year-old with a round that entered through her right eye. There was a memory of crime on every block. Was the entire city really that rotten? Could he not walk a hundred yards without passing the site of another tragedy?

Carberry had walked off his hangover by the time he reached St. Mark’s. Inside was dark and quiet. He took a seat in the back; there were a dozen empty pews between him and the next parishioner. Few people turned out for the Latin Mass, and when the service began it was clear that the attendees barely knew the language of Virgil. The silver-haired parishioners struggled to remember the sequence of sounds they heard strung together in church Sunday after Sunday when they were young. The Mass was just a chain of vowels and consonants they could follow into the past, signals they could track back to the experiences of their earlier selves, a direct connection to loved ones lost and roads not taken. At least nobody was trying to translate the liturgy through a pair of those damned lenses.

The Mass was just a chain of vowels and consonants they could follow into the past.

His thoughts drifted back over the long list of crime scenes he had handled. The case of the Esplanade rapist was unlike any of the others. He spent long days with Jimenez studying the evidence and interviewing witnesses, long nights in the shadows of that greensward by the Charles, watching, waiting for the man who was hunting young women along the river to make a mistake. And after months of attacks, he did. A victim grabbed the black bandana he wore to hide his face and twisted it to the side just long enough to see a man she vaguely recognized—a face she had seen on the sidelines at soccer matches when she was in high school, a guy whose gaze always seemed to linger a little too long. Jimenez scoured traffic cams and high school soccer websites until the pieces came together and led them to Joannan Academy, and a math teacher who earned a little extra money coaching girls’ soccer. They found the black bandana in his yellow VW in the school parking lot. When they brought him in for a lineup, the victim trembled and sobbed.

Late one night, while the teacher was in MCI Norfolk awaiting trial, Carberry was working a homicide in Roxbury. His pager began to shake and it wouldn’t stop until he borrowed a phone and called the number on the LED screen. There had been a fire. His house was a smoldering shell by the time he arrived, smoke drifting up into a starlit sky from embers glowing beneath the debris. The charred bodies of his wife and children were unrecognizable. He leaned against the lamppost at the end of the walkway, crippled by grief, and something brushed against his face. Tied to the post was a black bandana like the one he found in the teacher’s car.

Carberry shook with a rage that threatened to rend his mind, and for the next week he worked without sleep, searching for the killer who struck back on the teacher’s behalf. His attention focused on the teacher’s brother, who had done time for pistol whipping a Tedeschi’s clerk for $400. Carberry learned he had charged his car at a nearby filling station about an hour before the flames incinerated life as Carberry knew it. He hunted the man all over New England, accosting his friends on the street, leading searches through his relatives’ homes. The guards at Norfolk put a few questions to the teacher for him. But the brother was like a demon in the wind. He never laid eyes on him. Carberry would never let it go, but he had to step back from the job to deal with his grief. It was hard to comprehend how he endured such a loss, or how he coped with the news that the teacher walked free when the victim refused to testify. If the detective’s family wasn’t safe, who could protect her?

The monsignor turned the bread and the wine into flesh and blood. Carberry brooded on the crime that had robbed him of everything. Why was he still in Boston? Why was he drifting back into his role on the force? Because Boston was home, and because carrying a badge meant if he ever found the brother he could make him pay.

The monsignor was waiting on the church steps. “It is good to see you this morning, Carberry,” he said. “But I couldn’t help noticing that you didn’t join us for communion again …” His voice trailed off, turning the observation into a question.

“No, monsignor. I’m still not ready.”

Jimenez picked him up in her Subaru on Monday morning.

“How was your weekend?” Carberry said.

“Fine,” she said, looking at him sideways. “How was yours?”

“Oh you know me—dinner, a movie, Sunday Mass. Same old, same old.”

She pulled his car keys out of the pocket of her hoodie and handed them to Carberry without a word.

“We need to go back to Arbella,” he said, “and see what we missed.”

The video tech dutifully projected the images of Rachel and her friend riding up the elevator again. The guy had his back to the wall, and she stood right up against him. “I guess we all know what happens from here.”

“Let it run,” Carberry said.

Rachel pressed up against her beau and kissed him. The hat fell to the ground. The guy looked up, smiling.

“Right into the camera,” Jimenez said. “Like they know we’re watching.”

Carberry shifted forward in his seat. He was looking past the video monitor now, as if he were staring a hole through the cinderblock wall behind the desk. He thought back to Rachel returning to the room with her friend, and the body that wasn’t in the middle of Commonwealth Avenue. “The hat,” he said.

“We know what happened,” the sergeant said. “You’ve got witnesses. The girl goes back to the room with the guy. They’re in the corner together. She goes out the window.”

Jimenez shifted to the edge of her seat. “But no hat at the party,” she said. “Such an elaborate scheme, how could they miss a detail like that?”

“Nobody missed anything,” Carberry said. It had been very much like a performance, a piece of digital theater. “I think we need to pay Philip Townsend another visit.”

The afternoon sun was bright but the wind was howling down Clarendon Street when Jimenez parked by the Hancock Tower. The detectives passed through the chrome columns in the lobby and rode the elevator up to the ARkade Development offices.

“I’m afraid Mr. Townsend has a meeting …” an assistant said as Carberry strode into the executive suite.

“You’re going to need to clear Mr. Townsend’s schedule,” Jimenez said.

Townsend was behind his desk in a corner office with windows running from the parquet floor to the ceiling 20 feet above. Jimenez took a chair in front of the desk and Carberry took in the sweeping view of the city. The Charles turned by the Arbella campus and ran parallel to Beacon Street, disappearing behind Beacon Hill and the golden dome of the State House. “Tell us about the new glasses,” he said.

Townsend shifted pens and paperweights around his desk. “I’m not sure what you mean.”

Carberry started to pace along the wall of windows. It was sunny over the harbor, but dark clouds were moving in from the west.

“Look, I didn’t know about it,” Townsend said. “And by the time I did, there was nothing I could do.” Carberry let the silence press in on the man behind the desk. “I mean, I tried,” he said. “They told me they fixed the problem.”

“Why don’t you take a deep breath and start at the beginning?” Jimenez said.

Beads of sweat glistened under the strands of Townsend’s hair. He opened a bottle of water and took a drink. “We were testing the software for the ARkade rigs,” he said. “A few dozen units were shared under nondisclosure agreements with some of our heaviest users. The engineers wanted to see how the new rigs held up in the real world. We didn’t know someone could hijack the lenses.”

“We didn’t know someone could hijack the lenses.”

Carberry stopped pacing and folded his arms. He couldn’t hear the wind through the thick glass, but he could feel its energy running past. “Somebody found a way to manipulate the AR,” Townsend said. The new glasses included a feature allowing users to fully share an AR experience with the people around them. It was possible before, but it was clunky. Now it was seamless. Augmented events could be shared in the real world, in real time. “You aren’t holding your phone up between you and the world, you aren’t watching on a tablet. You’re walking around with a pair of lenses so light that you forget you’re wearing them. The rendering is so crisp you can’t even tell that it’s an overlay, or a virtual embed in the physical world.” A crowd could watch a SpaceX launch together in Copley Square as if the rocket were igniting in front of Trinity Church. You could go to the MFA and doodle mustaches on the Rembrandts for a lark, and the guards could watch you do it in their own rigs and giggle. “We thought we were taking memes to a new level,” Townsend said. “But somebody pushed things too far. When we started testing the new units in the real world, somebody started creating things that the users didn’t know were AR—extreme scenes, crimes, localized disasters. They were showing manufactured events, and people saw and heard them from different angles, based on the geolocation capabilities of the devices.”

Carberry sat down in front of the desk, scowling. “Like bank runs and SWAT raids?”

Townsend held his head between his hands. “This was never supposed to happen.”

“You knew all this, and you released the product anyway?” Jimenez said.

“This was a huge investment,” Townsend said. “We thought we could patch it up post-release, via updates.”

The daylight dimmed over the harbor. Townsend was wringing his hands. “Somebody wanted to learn what would happen if multiple users all saw the same fabricated experience.”

“They were creating alternative pockets of reality,” Carberry said.

“The engineering team was supposed to patch the problem,” Townsend said. “I’m not an engineer. I didn’t know it was so easy to exploit.”

“Your daughter knew, didn’t she?” Carberry said.

Townsend folded his arms across his chest. “She was interning in the lab when we discovered the problem,” he said. “I promised her I’d get it fixed.”

“I guess she knew better,” Carberry said.

“What are you insinuating, detective?”

“She exploited the code herself,” Carberry said.

“You don’t know that!”

“When we started testing the new units in the real world, somebody started creating things that the users didn’t know were AR—extreme scenes, crimes, localized disasters.”

“The whole scenario from the time she came back to the dorm room with her guy until her avatar landed on Comm Ave played out in the AR rigs nearby,” Carberry said. “Everyone wearing the glasses saw the performance from their own angle. The sergeant even got to watch her fall.”

“But why?” Townsend said. “I don’t understand.”

Carberry stood and walked to the window. Rain was beginning to fall. “She could have any number of reasons,” he said.

“Obviously, the virtual death of a local tech magnate’s daughter was guaranteed to call attention to the danger lurking in your new product,” Jimenez said.

“Or maybe she just wrote a scenario that let her slip away,” Carberry said.

“I didn’t know, Rachel …” Townsend said. “I don’t know what more I could have done. What could I do? Where is my daughter?” he demanded. “Where did she go?”

On the sidewalk below, Carberry saw a couple rushing toward Copley Station under a shared umbrella. It looked like a Black man with a redheaded woman, but it was difficult to see through the falling rain.

Jimenez pulled into the lot behind Doyle’s and parked beside Carberry’s Chevelle. Inside the dimly lit pub, they chose a booth in the first room under a relief of the Guinness toucan, and they ordered a couple of Cokes and cheeseburgers.

“You want a Coke?” the waitress asked.

Carberry grimaced. “Yes, a Coke,” he said, turning to his partner. “What were we talking about?”

“You’ve been coming back a lot lately,” she said.

“Is it a lot?” Carberry said. “Can’t be more than it used to be, right?”

“You want to talk about it?”

“Not really.” Carberry rubbed his fingertips into his temples.

Jimenez thought carefully about what she was going to say next. “You sure you have a handle on things?”

The waitress delivered the Cokes. Carberry took a sip and looked away. “I appreciate your concern, Gabi,” he said, “and I appreciate your help. Sometimes, you know, it all just washes over me again.”

“You’ve come so far, Carberry,” she said.

“You don’t have to come collect me anymore, Gabi. You have your own life.”

“No, it’s not like that,” she said. “Hell, the folks here at Doyle’s are practically family now.”

He permitted himself to smile. “Come on, before this week it had been months since you had to rescue me.”

“I know, I’m kidding,” she said. “But not really. I’m OK coming back here whenever you need me, just as long as you know where you are.”

He was puzzled. “I know the drinking has been heavy lately …”

“It’s not the Jameson’s that I’m worried about,” she said. “You could be drinking anywhere.”

“This is where I come, though,” he said. “It’s where I always came.”

“But you know where we are, right?” Her voice cracked and he recognized the look on her face. It was pity. “Tell me that you know what this is.”

Carberry looked around—a half-dozen patrons were sipping drafts and talking craic at the tables around them. He stood up and walked to the front room: the Celtics were playing the Sixers on the small screen at the far end of the bar; the barkeep was drying a pint glass with a towel; police patches taped to the back bar; green hats and shirts with bright orange shamrocks for sale on the shelf. His gaze drifted back to the TV: on top of the set, a pair of rabbit ears; on the screen, a gangly forward with uncombed blond hair wearing the number 33 on his white-and-green jersey sank a fadeaway from beyond the three-point line, and then he knew. Carberry balled up his fists and pressed them into his eyes.

“You get me now?” Jimenez said. She put an arm around his back. “The whiskey is real, but this place is just a VR depot.”

Carberry thought back to a time when the pub was full of cigarette smoke and neighbors stopping in for a pint after work, politicians brokering deals over drinks, musicians getting ready to play a set at Green Street Station up the hill. He tried to remember the first time he walked through the door. When did Doyle’s become a figment of a VR algorithm? If Doyle’s was a sim, what was real?

“No, I get it,” he said, trying to catch his breath. “Pay the check, will you. Shut this fucking thing off.”

“If Doyle’s was a sim, what was real?”

Carberry rushed out to the parking lot to breathe the summer air. The leaves of an old oak tree in a neighboring yard fluttered on a light breeze. The sky was bright blue and the clouds blazed white in the midday sun. Jimenez emerged from the side door of the bar, slotting her paycard back into her organizer.

“This was always the place, though, right?” he said. “I mean, this is where the pub was.”

“Right,” she said. The clouds drifted overhead. “My apartment?” he said.

“You want to go to your apartment?”

“No,” he said. “Is it real? Is the place I think is my apartment really my apartment?”

“Real,” she said. “Your car, too.”

He was silent for another moment.

“Taiwan Café?”

“I don’t get to Chinatown too often, Carberry, but I doubt it.”

“What about St. Mark’s?”

“It’s kind of a hybrid, I think,” she said. “A lot of the churches are using the main hall for regular services, but they’re still running VR downstairs, for Latin Mass and other programming for the old folks.”

“How about the Brattle?”

“Sorry, Carberry,” she said. “They tore it down to put up condos.”

“The fire?”

Jimenez put a hand on his shoulder. The leaves of the old oak tree shivered beneath the bright blue sky, and Carberry closed his eyes.