I spend my days thinking about collisions between tech—especially artificial intelligence—and society. There was a time when I could separate out that part of my day as work, but in 2025, such a division is no longer possible. Rather than simply think through these collisions, I now also live them, in nearly every corner of my life. AI is unescapable: I go to the grocery store and the radio is talking about the technology’s use in some sector or another. I go to get a haircut and we discuss smart mirrors that could show you virtual hairstyles to choose from. My child’s school insists on deploying some rather questionable software that claims to use AI to detect concerning behaviors or online communications and wants my consent to use it.

Which is to say that the fictional world Gregory Mone describes in “The Funniest Centaur Alive,” January’s Future Tense Fiction story, is uncomfortably real to me. The whirlwind of dilemmas and debates that buffet me in my work and life find familiar form in the story: questions about the authenticity of the human experience, pervasive surveillance, workforce displacement, AI sentience. Virtually every sentence found me muttering, “See what happens when you don’t have AI regulation?” or “If only we had a data privacy law.”

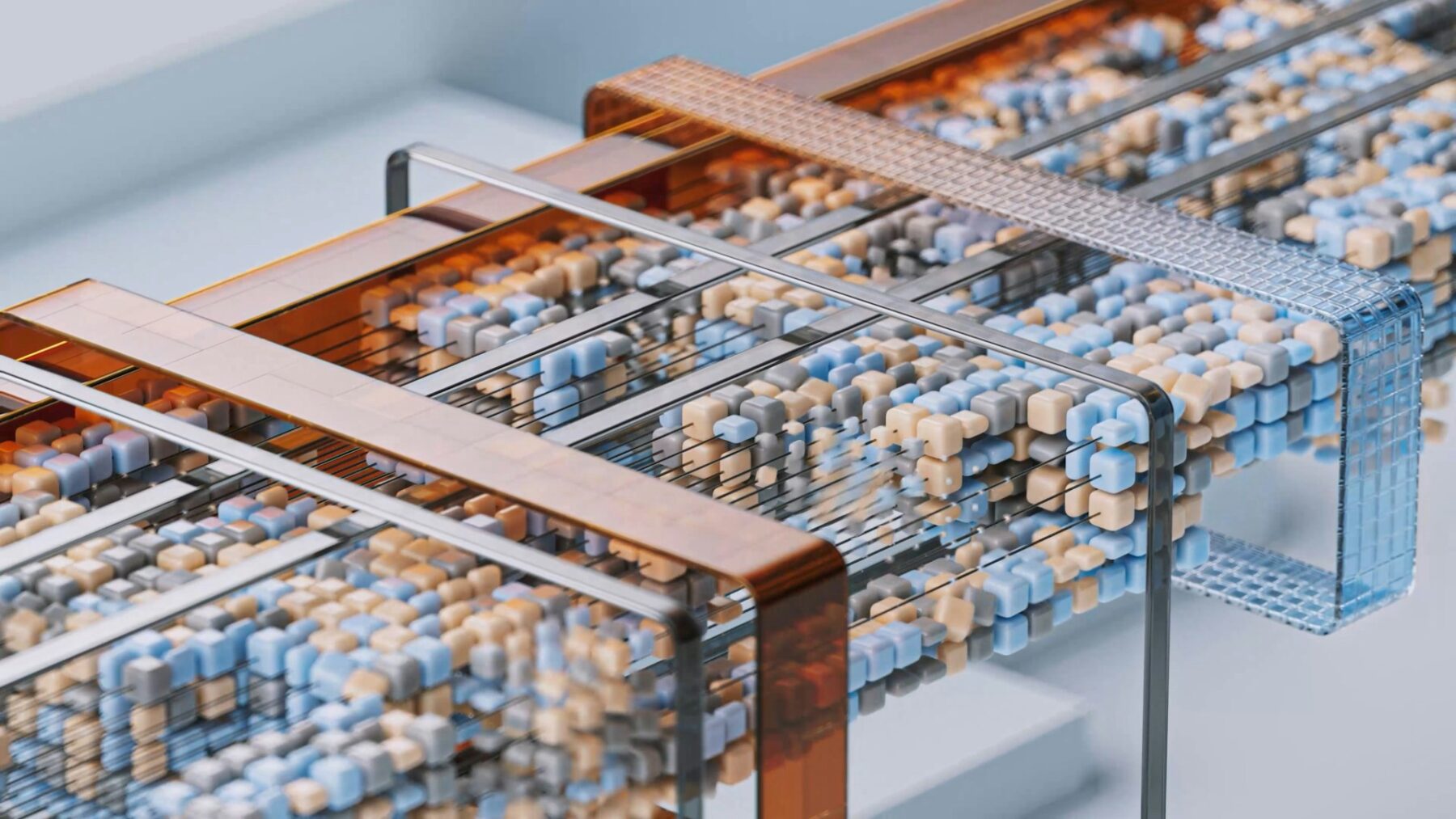

In short, the story follows two tech salespeople—Susan and Tim—at a conference in Las Vegas. Trying to blow off steam, they attend a stand-up show, where they watch a comic, Shen White, who has rapidly improved his act in an improbable amount of time. They suspect he’s used AI to do so—but contrary to established practice in this future society, he hasn’t disclosed his AI use. When Susan and Tim confront Shen about it, he reveals his secret: an AI-enabled headset that allows him to test thousands of versions of his routine with carefully constructed audiences, homing in on the funniest possible act for any given audience.

The story itself is a rather accurate mirror for my own anxieties about the AI-fueled world we already live in. I worry that we seem to lack the imagination and the will to create a society that’s better for all of us—not just a few. I worry that all we will end up doing is amplifying the worst parts of the world we live in now—more discrimination, more inequality, more rich people getting richer while the poorer and less privileged get left behind. And in a recursive twist, fears and anxieties about technology are also what motivate the story’s characters, who in turn don’t show up particularly well as human beings.

I worry that we seem to lack the imagination and the will to create a society that’s better for all of us—not just a few.

Tim is the only declared Centaur in the story, which is to say he’s a tech maximalist—using AI in every way he can to “improve” his productivity and efficiency, and disclosing this use, as required, by wearing a badge. Tim is fascinated by his augmentations, but seems depressed, resentful, and fearful about the future and his place in it. He begrudges his coworker Susan’s choice to stay away from technological enhancements, he feels bitter about being discriminated against for his own augmentations, and he shows surprisingly little interest in those used by Shen, the stand-up comic.

Shen is creative, and he has figured out a whole new way to use AI: channeling reinforcement learning and creating “trainers”—what technologists today would call “AI agents”—to help him with his act. But Shen’s barely disguised contempt for his “trainers” hides what seems like a deeper anxiety about his use of technology to hone (or replace?) his craft, alongside the need to please the funders that have made the technology possible.

Susan comes across as the most genuine, or dare I say innocent, of the three characters. She’s just like many of us, trying to stay authentic but not above taking advantage of an opportunity to get ahead. Yet even Susan is morally compromised by the end of the story. She feels the pain of betraying the AI “trainers” that Shen loaned her to perfect her sales pitch, but she rationalizes her betrayal by undermining the very humanity she felt coming from them—her promise is just a vector in a vector space.

Where does all this anxiety come from? It seems to reflect a striving for authenticity—and the contention that authenticity is central to the human experience. In a world where we increasingly live online, connect online, and build relationships online, we crave anything that feels real, tangible, tactile—in a word, authentic. This striving plays out on many levels in the story: There’s the idea that we should distinguish the Centaurs from unaugmented people, the tension between Centaurs and the “purists,” the human-only comedy club, the separate lines for Centaurs and non-Centaurs at security. (Having separate queues for augmented and unaugmented people actually makes sense to me .) And then there’s the setting of the story: Our characters exist among artificial trees, fake green ivy, and plastic chairs—all in Las Vegas, the most monumental example of something artificial trying to pretend to be authentic. I also found it amusing that Susan was concerned about the authenticity of her sales pitch—a performance that by its very nature might need to be inauthentic and manipulative.

In a world where we increasingly live online, connect online, and build relationships online, we seem to crave anything that feels real, tangible, tactile—in a word, authentic.

Reality and fiction blur. Back in 2025, we encounter demands that chatbots disclose that they are AI driven—there’s even a law in California mandating this. We privilege human communication and like to make fun of the perceived banality and stiltedness of large language models (“delve,” anyone?). We have heated debates about art and copyright—not just about ownership, but also about whether artwork made with the help of AI can be copyrighted at all.

These debates didn’t start with AI, of course. Recently, a music journalist from my favorite podcast, Switched on Pop, discussed how people reacted to autotune technology when it was first used. Was its use disclosed? Is it somehow cheating for an artist to use autotune to hide wavering in their voice? Do people feel betrayed by not having an authentic experience of an artist?

What’s left for a poor human to do, or be? Together with a historian at Brown University, I’m teaching a class on the history of AI. One of the tropes—or complaints, depending on who’s saying it—about AI is that every time we think we can define the boundary between human and machine, we’re proven wrong and have to start over. Automated computing—AI’s done that. Logical reasoning—done and done. Playing highly intellectual games like chess—hello, Deep Blue. Learning from past experiences—machine learning is everywhere. Rich language and conversation—say hi, Claude. Ironically, 60 years ago we thought rational thought and logical thinking was a test of humanness and intelligence. Today, emotion and the expression of feeling—and the intentionality that comes with it—appears to be the thing we now believe is fundamentally human.

AI is a mirror reflecting our anxiety back at us. To endeavor to define these ever-shifting boundaries is to attempt to understand what makes us ourselves. And in the face of technology that inches closer and closer to doing things we thought were the exclusive domain of humans, we have to keep changing what we think. The quest to define what makes us human is ongoing, and because AI mimics humans, what we deem as AI shape-shifts alongside us. This is, oddly enough, why I think we should not be making policy that focuses on AI. Instead, we should focus on “the point of impact with people”—how AI collides with us, in our everyday lives—and locate our policy guidance there. We should ensure that all technological systems that touch people’s lives are safe, effective, transparent, and clear, and don’t discriminate. And it shouldn’t matter whether they use AI, or machine learning, or statistics, or even an Excel spreadsheet.

Every time we think we can define the boundary between human and machine, we’re proven wrong.

“The Funniest Centaur Alive” dips into another major trope of stories about AI—that it’s alive. The idea of AI that comes alive (with usually dire consequences for its human creators) is one the oldest themes in literature. In the course I mentioned above, our first set of readings on this theme goes back to the Vedas. In more modern times, there’s always been a the-technological-slaves-will-rise-up-in-rebellion feel to these stories, which indicates (again!) a kind of insecurity or fear that we cannot be trusted to be good to our creations.

Shen—whose own relationship with his technological assistants is fraught—calls the AIs he’s developed to perfect his act “trainers” because “referring to them as agents,” he tells Susan, “sounds too … menacing.” I was tickled by this proposition, given that AI agents are the hottest thing in AI right now. As I write, OpenAI has just announced an interface that will allow you to have your browser be controlled by an AI agent; Anthropic also released a browser agent recently. It’s a reminder that the words we use to describe the technology we create shape our interactions with it.

The idea of an emergent intelligence arising from ever-more complex models dominates discussion in AI circles today, mostly because the commercially available large language models seem designed to make you believe they are kinda-sorta-alive. They’ve fooled software engineers, Nobel Prize winners, and innumerable people looking for love and connection, and have triggered a collective wave of hysteria among policymakers. I’m a skeptic when it comes to the “AI is alive” train—in part because what it means to exhibit consciousness is a very thorny question that researchers continue to grapple with at the most basic level. And that’s why my most important message when talking to policymakers about AI is that they should stay away from the panic and the paranoia, and focus on concrete harms and benefits that are based on actual evidence.

Otherwise, we risk getting caught in an AI house of mirrors—one that reflects our worst fears and inclinations, and obscures our agency to create something better.