Fully Accounting for America’s Research Investments

Far from being passive recipients of federal research dollars, universities pour in substantial resources of their own. It’s time to do a better job of documenting those investments.

The US research enterprise has long been one of the country’s primary drivers of wealth and prosperity. Its success has been enabled through a multi-stakeholder partnership involving the federal government, universities, philanthropy, and industry. But recent actions suggest the federal government is reevaluating its own role and questioning the value of universities’ contributions.

Universities are far from passive beneficiaries of this partnership; they are the locus of a significant portion of the nation’s research activities. Universities serve as the single largest sector performing federally funded research (approximately 30%), and they perform nearly half (46%) of the nation’s basic research. This federal investment has yielded enormous returns. But the standard ways of measuring these returns may employ models that underestimate the true value of university research for the US economy and the federal budget.

Moreover, universities make significant investments of their own into the research enterprise, including in infrastructure, equipment, systems, human capital (faculty, staff, students), and seed funding programs. These investments are necessary because university-based research is inextricably linked to a range of other missions associated with higher education, including teaching and training, community engagement, economic development, and clinical care.

Within the context of the larger federal reevaluation of the partnership, universities are revisiting how they understand, quantify, and talk about the range of critical roles they play to support the American people. In general, university efforts to communicate the impacts and outcomes of their research portfolios—the downstream effects—have overshadowed discussions around their upstream inputs. But quantifying those inputs could be a key strategy in shifting public recognition of the role of universities as enablers of the research enterprise.

Universities are starting to come together to address these challenges. For example, while developing the Financial Accountability in Research (FAIR) model—for which I served as a subject matter expert alongside others from academia, independent research institutions, industry, government, and philanthropy—we sought information from multiple data sources to test alternative models to today’s reimbursement system for facilities and administrative costs. Although our work was rooted in extensive real-world data and received broad support from universities, membership organizations, and scientific societies—not to mention bipartisan support in Congress—it also illuminated a gap in consistent practices for quantifying institutional contributions to the research enterprise.

Most of the metrics employed to quantify research activities at universities focus on outputs like scholarly publishing, faculty honors, patents, and economic impact—some more intuitive to track than others. But those achievements are only part of the story. Accounting for institutions’ own inputs—the investments and resources needed to accomplish the work that leads to so many positive societal impacts—has been equally challenging.

Within the context of the larger federal reevaluation of the partnership, universities are revisiting how they understand, quantify, and talk about the range of critical roles they play to support the American people.

The primary input metric used by both universities and the federal government has been financial expenditures related to performing research. At the highest level, the federal government tracks these research expenditures through the annual Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey, administered by the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES) of the National Science Foundation. The HERD survey was developed in 2010, replacing the similar long-standing Academic R&D Expenditures Survey, which ran from 1972 to 2009. The data are sourced annually through voluntary responses from the hundreds of institutions that spend over $150,000 on research in a given year. These academic institutions encompass many institutional types with different missions and available funding sources. Among other data, institutions report their research spending from federal, institutional, business, nonprofit, and state and local government sources.

As the only publicly accessible database for comprehensive financial information about research activities by funding source, the HERD survey is a critical resource for a range of purposes. These include benchmarking analyses by universities and agencies, institutional classification criteria in the updated Carnegie Classification of Research Universities, and university ranking schema like the Interdisciplinary Science Rankings. The HERD survey is also used in federal legislation, such as the CHIPS and Science Act’s definition of emerging research institutions.

However, when it comes to providing a complete and accurate accounting of expenditures originating from institutional sources, the survey has significant shortcomings. Even though it provides definitions and instructions for reporting institutional expenditures, the way universities calculate those figures—and what their internal accounting systems allow them to capture in terms of these contributions—appears to differ widely. A June 2023 survey of campus administrators responsible for completing the HERD survey found that the most difficult expenses to capture and report typically relate to institutionally financed research. That survey also confirmed just how variably institutions include and measure a range of internal cost categories. My own experience working in the research offices of two universities, as well as discussions with research officers across a range of institution types, reflects similar patterns.

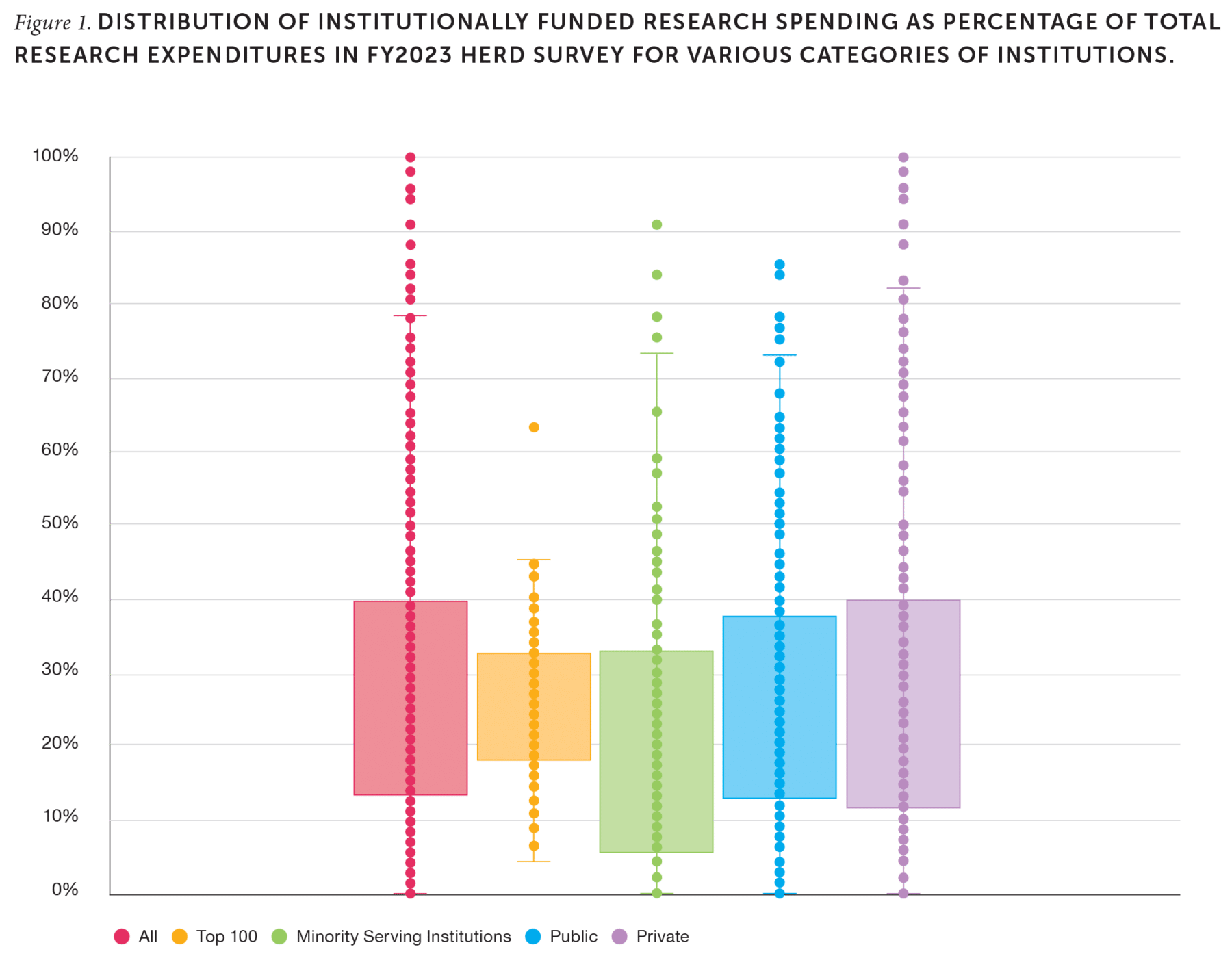

This underlying variation shows up in the data. For example, there is incredibly wide variability in reporting institutionally funded research expenditures as a percentage of total spending. There is considerable variability over time as well, where some institutions historically reported $0 in institutional expenditures, but hundreds of millions in subsequent years. In the most recent survey (FY2023), the 645 institutions that responded using the standard form reported a wide range of institutionally funded research expenditures, even in subsets such as the top 100 institutions in overall research spending, minority-serving institutions (MSIs: historically Black colleges and universities and Hispanic-serving institutions), public institutions, and private institutions (Figure 1). One would expect the largest research universities to have similar scales of institutional investments in graduate education, faculty salaries, and infrastructure required to perform similar levels of sponsored research; however, a comparison of two public research institutions with medical schools and very high levels of federal expenditures (University of Michigan and University of Washington) shows a substantial difference in the proportion of expenditures from institutional sources as a fraction of their total spending (35% and 7%, respectively).

Even if universities manage to capture everything allowed in the reporting guidelines for the HERD survey, it is likely that institutional investments in research are widely underreported. Many costs related to research are excluded from spending categories, including unrecovered indirect costs that exceed negotiated rates, estimates of faculty time, capital projects related to renovation or construction of research facilities, and various costs related to graduate student stipends funded through institutional sources. Propagated across all institutions, this highly variable and systemic underreporting results in billions missing from the accounting of America’s research investments.

Many universities have developed more holistic alternative methodologies to calculate their true contributions to research. For example, in early 2025, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s vice president for research described how its institutional investments were nearly as much as its externally sponsored research and that institutional resources had been the primary driver in the institution’s research growth over the last 10 years. Also in 2025, Vanderbilt University and Washington University in St. Louis released a white paper describing their joint effort to quantify the significant cost of complying with federal regulations—the vast majority of which were related to research.

These efforts are steps in the right direction, but more enterprise-level actions are necessary for universities to better demonstrate to taxpayers and decisionmakers the full range of their contributions to keeping the research enterprise running.

To begin, the HERD survey methodologies should be updated to encourage more consistency in what institutions report, and they should be expanded to better represent the true costs of research. The survey should also ask institutions to break down their institutional spending by category (e.g., space and equipment, graduate fellowships, compliance costs, competitive seed funding, faculty effort). Because research activities are often intertwined with other missions like teaching, community engagement, and clinical care, it may be difficult to untangle the range of input investments for research alone; however, this transparency would make clear how universities make essential investments in the people, programs, and other key infrastructure necessary to sustain American research leadership.

More enterprise-level actions are necessary for universities to better demonstrate to taxpayers and decisionmakers the full range of their contributions to keeping the research enterprise running.

Additionally, the HERD survey should request information on the sources of funds that allow universities to make institutional investments. Outside of sponsored programs, the main sources of universities’ revenue are relatively limited, including tuition, current-use gifts, endowment returns (the vast majority of which are restricted to specific purposes such as scholarships), clinical care (for those with academic medical centers), and state appropriations. Greater transparency will force conversations about the necessary trade-offs required in continuing university-based research if the federal government scales back its investment. Simply put, the only way for universities to continue providing such a high return on investment through research and development activities will be to increase revenue from these other sources.

NCSES administers several other helpful surveys alongside the HERD survey that could further inform quantifying inputs—such as data on research space and equipment and the scientific workforce—but these surveys are often disconnected from methodologies or processes related to completing the HERD survey. The Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering, for instance, reports that nearly 60% of 2023 PhD students in science, engineering, and health are supported using institutional funds, but differences in definitions and metrics (and who completes the surveys within an institution) can vary significantly, and the data linkages across these surveys are unclear. Ensuring these surveys are consistent and can be readily compared would aid understanding and quantifying all the ways institutions contribute to the research enterprise.

Associations like the Association of American Universities and the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities could bring institutions together to create standards or develop best practices for testing, as they did in the development of the FAIR model. These groups or others like them, such as the Federal Demonstration Partnership, can use their convening power to foster discussions between the federal government and universities and help ensure such an effort is both effective and inclusive across institution types. And for emerging research institutions, capacity-building needs to be part of the effort, with larger partner institutions providing lessons and serving as models. Philanthropies or the federal government itself can play a funding role through programs like NSF GRANTED (Growing Research Access for Nationally Transformative Economic Development).

There are precedents for this type of association-led effort, even beyond FAIR. For example, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) undertook the 2015 Academic Medicine Investment in Medical Research survey to quantify institutional research inputs for medical schools, including capturing some categories not collected by the HERD survey. Based on responses from 46 institutions, the findings indicated that medical schools themselves invested $0.53 for every dollar of sponsored research received in FY2013. Given that the growth of institutional support for research has outpaced the growth of federal research support over the past decade, this ratio has likely increased since then. AAMC began collecting responses as part of an updated survey in fall 2025.

A more complete accounting of institutional research inputs would complement efforts to develop a broader set of metrics capturing the quality and impact of federal investments in research, such as regional employment, translation of ideas into the marketplace, development of treatments and cures, and training the future highly skilled workforce. Research consortia like the Institute for Research on Innovation and Science (IRIS) have linked university research expenditure data to purchases, providing hard data on the locations and types of businesses supported by federal research dollars. These types of data are essential to show that federal dollars received by universities do not simply stay on campus but generate quantifiable economic impact in the region and state as well as around the country. IRIS also uses census data to capture the paths students take after they graduate, including those who were supported on federal research grants. Today, IRIS includes about 30 research universities across the country—just a subset of the institutions that perform federally sponsored research. Whether through efforts like IRIS or those facilitated by membership organizations, expanding such activities to include a more comprehensive set of institutions will be essential.

With growing pressures on higher education institutions to explain their value to society, universities need to prepare to provide more transparency about their essential role in the partnership driving America’s research enterprise. A collective effort to take stock of institutional commitments will do more to protect the enterprise than an approach that forces individual institutions to answer on their own.