Connecting the Dots for Defense STEM Workforce Development

Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, quantum systems, biotechnology, and hypersonics are reshaping the nature of conflict and deterrence, underlining the importance of maintaining innovation capacity to ensure national security. Alongside research, technology translation, and manufacturing, a highly skilled science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—STEM—workforce is a critical component of innovation infrastructure. Thus, the United States should treat STEM talent development as a core pillar of national security, on par with modernizing weapons platforms, rebuilding industrial capacity, and securing supply chains.

Historically, the Department of Defense and the hundreds of large and small businesses, organizations, laboratories, and facilities that make up the US defense industrial base (DIB) have played a major role in providing opportunities for STEM workforce training and education. Their outreach efforts—ranging from scholarships and science fairs to internships, mentorships, and postsecondary partnerships—have been designed to inspire future talent, raise awareness of defense careers, and broaden participation in STEM.

But these offerings have not developed in a coordinated manner. Many programs and services were created to address the specific or immediate needs of small segments of the vast defense enterprise. For example, in 2022, the National Math and Science Initiative partnered with the Chattahoochee Country School District to launch a college readiness program to build STEM skills and improve school experiences for the district’s 1,000 students, half of whom are from military-connected families stationed at Fort Benning in Georgia. Hundreds of other similar initiatives and programs—many successful—target other specific populations or segments of the workforce.

65% of defense companies reported difficulty hiring qualified STEM workers, and over half identified persistent shortages of skilled technical talent as a direct threat to meeting contract requirements.

As a result, even with strong intentions and substantial activity, DOD and DIB efforts have evolved as parallel, decentralized initiatives rather than a coherent system. In turn, investments in preparing the defense STEM workforce have created meaningful opportunities for scattered individuals without producing a coordinated national pathway into defense-related STEM careers.

This lack of coordination has consequences. According to the National Defense Industrial Association’s Vital Signs report from 2023, more than 65% of defense companies reported difficulty hiring qualified STEM workers, and over half identified persistent shortages of skilled technical talent as a direct threat to meeting contract requirements. Without a system that connects early outreach, postsecondary education, and employer needs, efforts are duplicated, capacity develops unevenly across regions, and promising learners fall through the gaps.

A deeper understanding of the breadth of current STEM engagement efforts across the DOD and DIB ecosystem, along with an examination of the structural gaps that inhibit greater collaboration between sectors, is necessary to align resources and prepare the talent needed for long-term US technological leadership. As researchers and former defense executives, we have performed such an analysis. Through a combination of literature reviews, stakeholder interviews, and a targeted survey of over 900 defense-related firms, we developed a systems view of the interdependent relationships underpinning the broader defense STEM talent ecosystem. Through this lens, it is possible to observe new opportunities to build a more unified approach to sustaining the national security STEM workforce.

STEM pathways for national security

Traditional approaches to STEM education tend to promote the four-year degree as the default path to a STEM job, but much of the training necessary to meet the needs of the science and technology enterprise happen outside this trajectory. The National Academies’ 2017 consensus study on building a skilled technical workforce noted that workers with less than a bachelor’s degree who possess strong science, engineering, and technical skills play an essential role in supporting the nation’s STEM capabilities. In response, higher education institutions and companies across the country are expanding their use of certificates, microcredentials, and other nondegree pathways to offer more flexible points of entry into technical fields. But the systems designed to support these learners remain uneven: High school students typically receive limited guidance about alternative pathways; community colleges and technical institutes are chronically under-resourced; and the lack of standardization and coordination across credentialing bodies makes the landscape of certificates and badges difficult to navigate.

Amid these obstacles, the defense sector offers a distinct point of leverage within the broader STEM ecosystem, both because of its scale as well as its reliance on an unusually wide range of technical domains. As one of the nation’s largest employers, DOD engages learners across almost every major STEM field and requires expertise spanning advanced technologies, engineering, data science, health care, human performance, logistics, and procurement. Yet the many programs intended to support the development of this technical expertise often emerge independently, without a shared framework or coordinating structure.

The many programs intended to support the development of this technical expertise often emerge independently, without a shared framework or coordinating structure.

As a result, resources to support the STEM workforce are dispersed across DOD. The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering oversees a central DOD STEM strategy, anchored by a small set of flagship programs. One such initiative, the Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation (SMART) Scholarship for Service program, targets recruitment and retention of advanced STEM talent by making full-tuition awards to students in exchange for committed service at DOD laboratories and engineering centers after graduating. The program has awarded more than 4,200 scholarships since 2006.

In parallel with centrally supported efforts, the Army, Navy, Air Force, and other DOD components operate their own suites of programs, each setting priorities tailored to mission needs and conducting evaluation according to their own standards. STARBASE, for example, reaches between 70,000 and 90,000 fifth-grade students each year through immersive STEM learning experiences on DOD installations. The Army Educational Outreach Program engages more than 55,000 students and teachers annually across apprenticeships, competitions, research experiences, and summer programs designed to build foundational STEM skills and introduce participants to Army scientists and engineers. The Air Force’s Leadership Experience Growing Apprenticeships Committed to Youth (LEGACY) initiative offers a progressive series of camps, internships, and apprenticeships from middle school through college, creating a continuous pathway for students to explore STEM careers linked to Air Force missions. While these component-level efforts create valuable opportunities, their diversity in goals, target populations, and evaluation approaches contributes to the broader fragmentation of DOD’s overall STEM workforce landscape.

Beyond DOD, the defense industrial base also plays an active but distributed and uneven role in STEM workforce education and development. Larger companies, which are typically publicly traded and well resourced, are more likely to support strategic engagement efforts like partnerships with school districts and universities, internship and early-career pipelines, and online resources for students and teachers. Many of these firms also maintain dedicated teams or corporate foundations that manage long-term investments in STEM education. By contrast, small and midsize firms tend to concentrate on episodic activities such as sponsoring student competitions or hosting interns.

Among the most common forms of outreach across the DIB is K–12 engagement. Many firms encourage STEM-related volunteerism and employee participation in educational competitions like FIRST Robotics and CyberPatriot. Industry-sponsored scholarships, including graduate fellowships at the master’s and doctoral levels, are another common form of engagement that builds advanced expertise aligned with defense industry needs. And finally, large-scale research collaborations, typically undertaken by the largest DIB firms, like Boeing’s Advanced Research Collaboration at the University of Washington, have also become important means of university-industry engagement.

Less frequently occurring are comprehensive, cross-sectoral partnerships between the government, universities, and industry. Fewer than 20% of the firms we surveyed reported any STEM education–related collaboration with DOD entities. Those that did described informal, ad hoc partnerships rather than structured or strategic engagements. Likewise, firms rarely noted collaborations between DOD and the DIB with community colleges—despite their critical role in developing a skilled technical workforce.

A strategic view

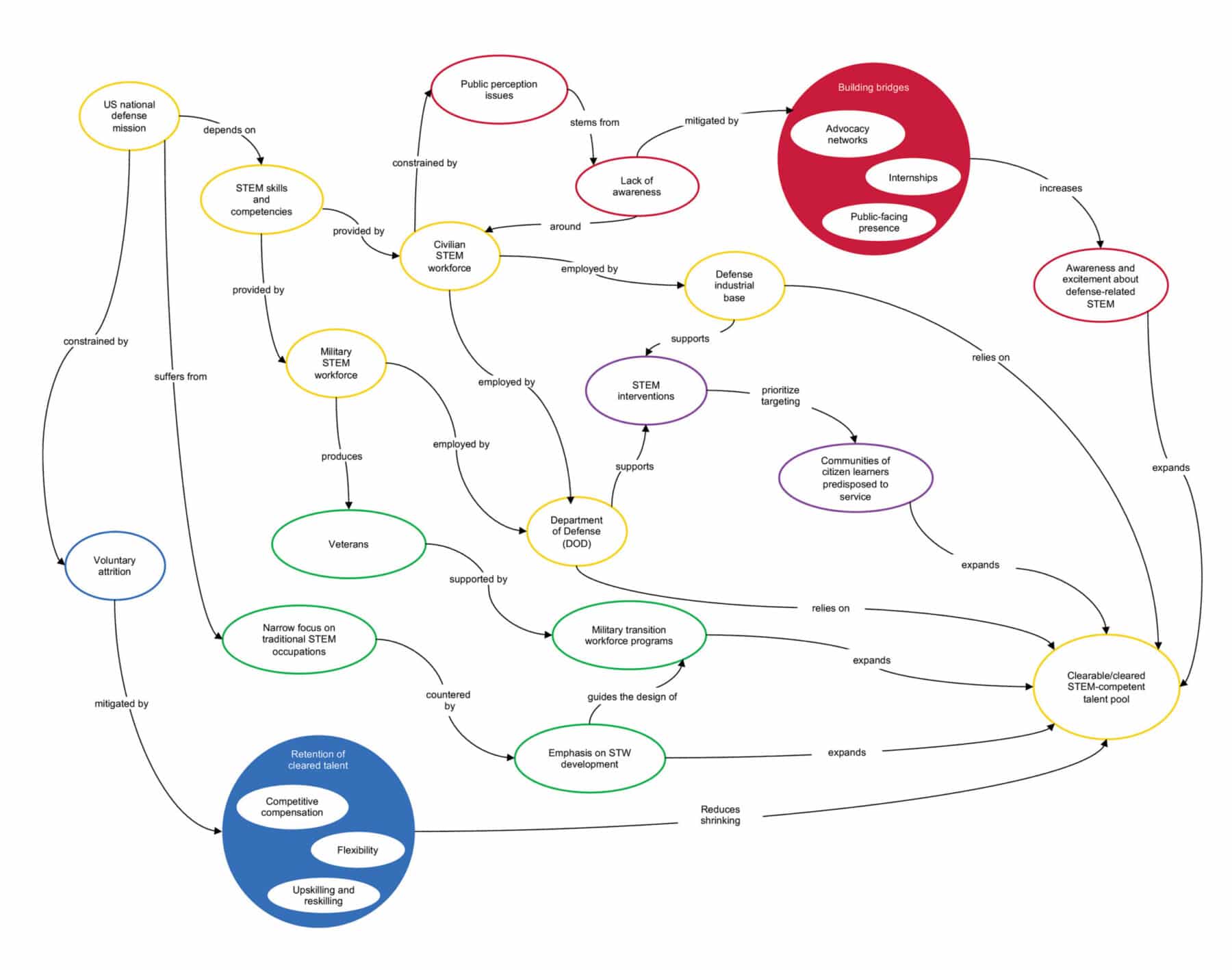

To welcome more of the American population into the sector, the defense sector must better align resources for STEM education and training to accommodate more diverse routes into the STEM workforce. We developed a systemigram—a systems-level visual narrative that maps interdependent relationships, opportunities for alignment, and leverage points that shape this space—to better understand the fragmented and complex landscape of national security STEM talent development. Rather than mapping every program, the systemigram distills the most critical insights from our research into a focused and actionable representation of the broader ecosystem.

The diagram is color coded, with the connections between the stakeholders highlighted in yellow along the diagonal (starting at the top left corner and moving toward the bottom right) representing the mainstay of the ecosystem: The national defense mission relies on civilian and military STEM workers whose skills and competencies support DOD and the DIB and who have or are able to attain security clearances. The purple elements represent standard (though arguably underutilized) approaches to reaching new learning communities to attract more clearable talent.

The systemigram shows that challenges to the defense STEM workforce build across the entire system, so fixing only one part of the pipeline will not be enough.

The red elements represent different ways that low visibility, public misperceptions, and lack of awareness depress interest before individuals even enter the workforce. Many prospective workers are unaware that most defense STEM roles are civilian or that DOD and the DIB offer access to unique research facilities and complex technical challenges. Countering these misconceptions requires efforts that highlight career opportunities, the remarkable resources available for defense research such as supercomputers and hypersonic test facilities, and the size and accomplishments of the civilian STEM community.

The blue elements show the reasons that skilled workers may leave the defense arena, and present possible opportunities for retaining cleared technical talent to avoid the cost and time of rebuilding talent that is lost.

And finally, the green elements speak to the role of veterans in the skilled technical workforce. Poor alignment between military and civilian occupational classifications and a lack of understanding around the occupational roles of the skilled technical workforce deter transitioning service members and veterans from entering those high-demand fields. Greater awareness of job options, along with better recognition of the portability of military-acquired skills, enables veterans to identify the skilled technical careers they already qualify for or could access with only modest additional training.

The systemigram shows that challenges to the defense STEM workforce build across the entire system, so fixing only one part of the pipeline will not be enough. It also demonstrates that the defense technical workforce is broader than many decisionmakers realize, spanning civilian scientists and engineers, skilled technical workers, and veterans whose skills are often underrecognized. Improving visibility, strengthening pathways, and making military skills more portable can help unlock talent that is already available but not fully tapped.

Connecting the dots

To build enduring STEM workforce training and education systems for the defense sector, more cross-sectoral partnerships capable of scaling, adapting, and delivering measurable impacts are necessary. This means investing not just in programs, but in the connective tissue between them: shared infrastructure, aligned goals, coordinated data, and sustained leadership across sectors. Three models in operation within the defense sector and beyond are emblematic of this approach and should be considered in the coordination of new efforts.

Isolated efforts, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot match the pace or complexity of modern workforce demands.

First, Manufacturing USA—a network of 18 institutes focused on accelerating manufacturing innovation across emerging technologies, from robotics to biofabrication—operates as a network of public-private partnerships that provide applied research, technical training, and industry-aligned curricula. As of 2019, more than $3 billion had been invested in establishing and operating the Manufacturing USA institutes, including over $2 billion contributed by industry and nonfederal government partners. The individual institutes support initiatives for upskilling, credentialing, and certification to strengthen manufacturing career and technical education pathways in the defense-industrial workforce, some of which specifically target transitioning service members, military spouses, and veterans. The network recently produced a framework of necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities for advanced manufacturing fields to guide workforce development efforts throughout the ecosystem, which similarly highlighted the need for further coordination between and across sectors.

A second significant partnership is the Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P-TECH) model, a public-private initiative that integrates high school, community college, and workplace learning. High schools provide the foundational resources and implementation support; community colleges offer faculty and college-level coursework; and industry partners identify needed workplace skills and provide real-world experiences such as site visits, guest speakers, project days, and paid internships that help students graduate career-ready. Through greater access to work-based and college-level learning opportunities, P-TECH students are 38% more likely to secure internships during high school, more than twice as likely to complete at least one college-level course compared to similar peers, and complete associate degrees four times faster than the national average at postsecondary institutions. The number of P-TECH schools has grown to more than 240, linked to nearly 200 community colleges and more than 600 industry partners across the world. While not defense specific, P-TECH’s structure makes it an ideal platform for building tailored pipelines into national security roles. Several DIB firms already participate, including Corning Inc. at the Greater Southern Tier STEM Academy in New York and CISCO at Carter P-TECH in Dallas. The model’s adaptability across urban and rural settings further enhances its value.

Finally, additional opportunities lie in partnerships with trusted youth-serving organizations such as 4-H, which already reaches millions of students with STEM programming. In particular, the 4-H Military Partnership—a collaboration between military services, land grant universities, DOD, and the US Department of Agriculture—offers a unique channel to involve military-connected youth in research-based programming in their local communities. When government and industry co-design programs, align incentives, and track outcomes together, the results can exceed the sum of their parts. Isolated efforts, no matter how well-intentioned, cannot match the pace or complexity of modern workforce demands. DOD and the DIB face shared risks from STEM talent shortfalls, but they also share a unique opportunity to shape the next generation of national security STEM professionals, together. Congress and DOD can accelerate progress by directing and resourcing targeted public-private partnerships while requiring shared metrics, data, and accountability for outcomes. Building such coordinated, mission-driven partnerships will enable the US defense sector to treat the acquisition and development of the next generation of STEM talent as a core strategy, not an add-on.