Butter Cows and Seed Art and Participatory Spectacles

State fairs create an intersection for rural and urban life, connecting fairgoers with agrarian knowledge and heritage, even though fewer than 2% of Americans are farmers today.

State fairs today are extravagant showcases of knowledge, creativity, invention, and production. Occurring in late summer and into fall, these modern-day harvest festivals display knowledge and talent in giant open-air living museums where people can enjoy various ways to participate, contribute, compete, and learn. Initially focused on the practices and products of agricultural life in the 1800s, they are now events that connect attendees and participants with an agrarian past, even though fewer than 2% of Americans are farmers today. Although agriculture remains at the core of state fairs, they have evolved to showcase the crafts and talent of the general populace as well as introduce immigrant culture and traditions. International cuisine and novelty foods—for example, anything “on a stick”—have become some of the biggest drivers of attendance.

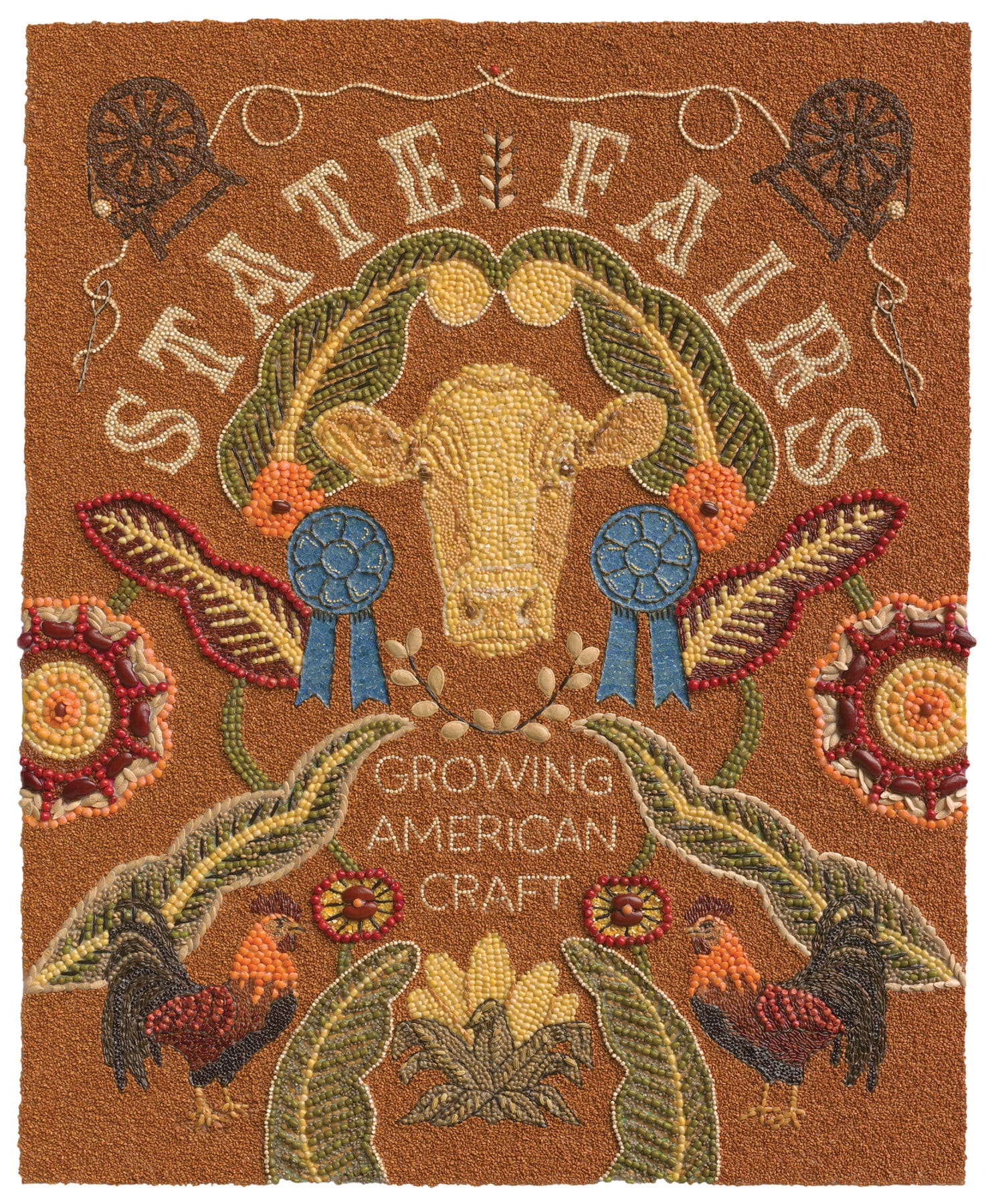

I have studied the Minnesota State Fair for years, particularly the crop art competition, where crafts like seed art offer Americans of all backgrounds a way to participate in traditions with origins in rural heritage, while also employing innovation and humor. Tens of thousands of people enter their creations in state fair competitions each year—an overlooked phenomenon that deserves the attention and analysis it receives in State Fairs: Growing American Craft, which opened atthe Smithsonian Museum of American Art’s Renwick Gallery in summer 2025.

Organized by agricultural societies in the early nineteenth century—the first US state fair was held in Syracuse, New York, in 1841—state fairs were conceived as educational experiences rather than farm markets. Displays of crops, food stuffs, and animal breeds were intended to share knowledge to improve agriculture, food supplies, and products such as wool.

These fairs gradually evolved from simple showcases to competitions with ribbons and cash prizes awarded for the best in categories such as corn, wheat, vegetables, and dairy, as well as livestock such as cows, horses, pigs, and sheep of various breeds. Participation was a way for everyday farmers to boast of their agricultural assets and learn how to improve them with new seed varieties or livestock breeding opportunities. Craft activities eventually became a standard feature of state fairs, often through the addition of a “women’s building” to recognize the critical skills of farm women in making cloth, clothing, quilts, embroidery, baking, and canning.

State fairs brought together a mix of thousands of people from rural areas, small towns, and cities. They played a key role in promoting their respective states as attractive places to settle and farm as they competed for population and business investments. Displays engaged in over-the-top braggadocio to tout such qualities as the richness of a state’s soil and pastures, the industriousness of farmers, the abundance of processing businesses, and the ability to move crops and livestock to markets.

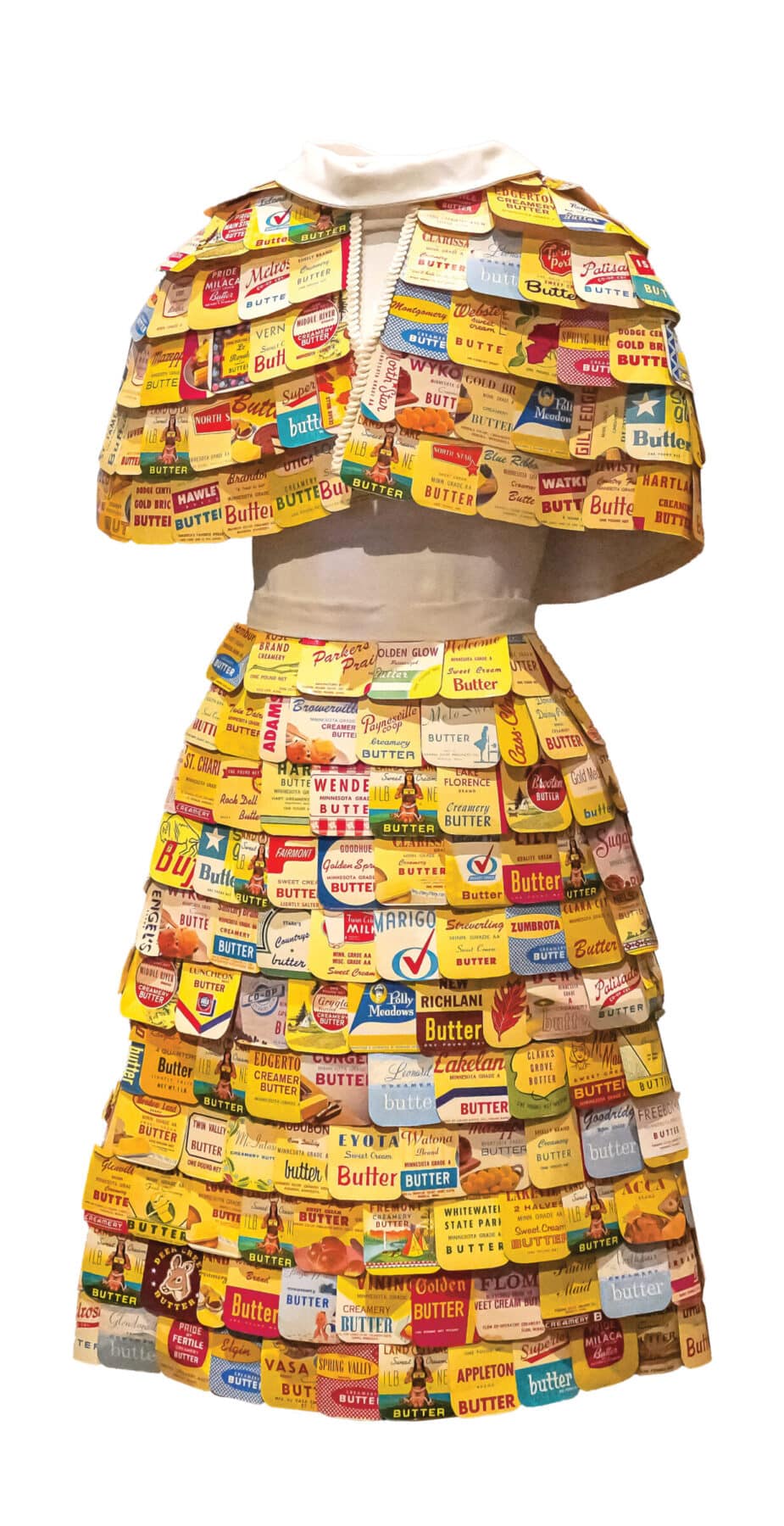

Some of these hyperbolic displays borrowed from farm crafts that were given new meaning by industry, professional artists, and display merchants, as happened with butter sculptures. In the 1800s, farm women added beauty to their home-churned butter by using decorative molds. At fairs, however, professional sculptors used butter as if it were clay to create large-scale sculptures to promote prosperous dairy farms and related industries.

These large-scale butter spectacles took off in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when states were invited to showcase their agricultural riches at international expositions such as the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. At the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904, Minnesota won a gold medal for its life-size butter tableau of Father Louis Hennepin, a Catholic priest from Belgium who came to what would become Minnesota in 1680 with a group of explorers to survey the upper Mississippi River. Sculptor John K. Daniels showed Hennepin with an Indian guide debarking a canoe that was tethered to shoreline bushes, with the rippling Mississippi beneath. Unlike other entries that used underlying armatures covered with butter, Minnesota’s entry was carved from solid butter and displayed in a refrigerated case. In 1911, Daniels created a life-size cow out of butter for the Iowa State Fair by sculpting over a wire armature.

The butter cow currently on display at the Renwick Gallery was crafted by Sarah Pratt and her twin daughters. Pratt, who has been sculpting the annual cow for the Iowa State Fair since 2006, learned from Norma Lyon, who became Iowa’s “Butter Cow Lady” in 1960. In 1911, butter cows delighted rural audiences that were personally familiar with all the details of real cows. Today, these same sculptures appeal to visitors who may have never actually been near a cow.

In 1965, in an effort to remain relevant to contemporary audiences, the Minnesota State Fair began to feature a live butter-sculpting experience in the Dairy Building, which continues to this day. The demonstration is a novelty act in which an artist sculpts “butter heads” of the young women vying for the title of Princess Kay of the Milky Way to represent the state’s dairy industry in public appearances. The sculptor (who changes year to year) and individual contestants, clad in snow suits, sit for several hours in a glass-walled room cooled to 40 degrees to keep the butter firm. As the artist sculpts a 90-pound block of butter, the case rotates so fairgoers can view the activity from all sides. Until recently, butter remnants from the sculpting process were spread on saltine crackers and given away to onlookers. Each finished sculpture is featured on its own pedestal within the case. At the close of the fair, the Princess Kay contestants get to take their butter sculptures home.

Also in 1965, the Minnesota State Fair launched another innovation: a new “crop art” competition intended to connect urban and suburban Minnesotans with agricultural knowledge. Although crafts had long been promoted in the Creative Activities Building, the crop art was featured in the Farm Crops area of the Agriculture-Horticulture Building (known as Ag-Hort) alongside prize-winning examples of fruits, flowers, vegetables, grains, and trees. Orris Shulstad, then the fair’s superintendent of farm crops, launched the crop art competition to attract attendance at the Ag-Hort Building and to encourage Minnesotans to learn about what crops grew in the state. As he and others set up the crop art competition, they specified that only seeds from Minnesota crops and cultivated plants could be used as materials to create mosaic-like images. In this way, both rural and urban folks now learn about the state’s crops and what the seeds look like. Each submission is required to include a legend card with a list of individual seed names and plant materials, such as pine needles or corn husks, with samples of each material glued to the card.

The work of “crop artist” Lillian Colton of Minnesota demonstrates how the experiences of farm life gave rise to new forms of creativity that became central to state fair competitions. Seventeen of her crop art portraits of famous people are featured in the Renwick exhibition, along with six portraits created by her daughter, Linda Paulsen.

Colton’s life as a farm girl shaped her training and visual aesthetic, eventually leading her to work as an artist of seeds. Born in 1911 in southern Minnesota, she grew up helping with farm chores, playing with a pet duck, braiding twine to make a harness for the family’s chicken, and participating in the Clover Leaf Farm Club. She and the other club members would create booths each year for the Martin County Fair, featuring groomed and smoothed grain stalks from oats, wheat, barley, and flax in bundled shocks, displayed along a back wall. In front of the shocks, they placed jars of cleaned grain seeds. The first year, the club won a blue ribbon. “Memories of shocking oats and helping with the farm club exhibit the Martin County Fair has instilled in me the beauty and use of grains and seeds,” she noted.

Smitten with fair fever from her childhood on, Colton continued to participate in craft competitions even after becoming a hairdresser, marrying, and raising children. After seeing the first crop art competition in 1965, she made her first picture of a grouse because she thought seeds would best convey the textures and colors of the bird’s feathers. Colton got some of her seeds from the farm wives whose hair she cut, purchased some at local feed stores, and found others in her kitchen pantry. After the grouse, she created a horse and a bear. But in 1969 she wanted to win a ribbon, so she made a bold move: a portrait of President Nixon. Her thinking was that most other crop art pictures were landscapes or Americana imagery based on embroidery designs and no one else

did portraits.

Colton succeeded in getting the judge’s attention and won Best of Show for her Nixon portrait—the first of 12 Best of Shows she would go on to win. Colton became known for her portraits of famous people, including presidents, movie and television stars, musicians, athletes, Grandma Moses (the elderly painter known for her quaint farm and small-town scenes of bygone eras), and Andy Warhol. After many years of consistent wins, Colton retired from the crop art competition in 1983 to give newcomers a chance.

Into her 90s, Colton displayed her portraits next to each year’s entries. And every afternoon of each 10-day fair, she demonstrated how to do crop art while describing the seeds she used. Her daughter Linda continued to compete in crop art, excelling at portraits of Lucille Ball and Dolly Parton.

Inspired by Colton’s new direction in crop art subject matter, younger artists have continued to innovate and expand into new subjects. One artist regularly memorializes a person who died the preceding year, focusing on political activists and social justice advocates. Another adapts children’s books, giving them political twists. Artists have begun incorporating new types of seeds gathered from immigrant markets in the Twin Cities.

In recent years, the crop art competition at the Minnesota State Fair has exploded in popularity, causing the farm crops superintendent to double the space devoted to the display. In 2025, the number of registrations shot up to nearly 800, twice as many as the previous year, with a record 450 people submitting pieces and all submissions being displayed.

Lillian Colton’s childhood on the farm provided her with a familiarity with seeds that could be used as a medium for art, laying the groundwork for current creatives. Today, most crop artists don’t have a farm background, but using seeds reminds both artists and viewers of where our food comes from. Fair competitions bring people together to celebrate not only the state’s crops, but also the things that make us citizens of that place: tactile relationships, a connection to land and nature, and knowledge and appreciation of farming.