Biotechnology regulation

Henry I. Miller and Gregory Conko’s conclusion that global biotechnology regulation should be guided by science, not unsubstantiated fears, represents a balanced approach to the risks and benefits of biotechnology (“The Science of Biotechnology Meets the Politics of Global Regulation,” Issues, Fall 2000).

Despite biotechnology’s 20-year record of safety, critics in Europe and the United States have used scare tactics to play on the public’s fears and undermine consumer confidence in biotech foods. In response, many countries have established regulations specifically for agricultural biotechnology and have invoked the precautionary principle, which allows governments to restrict biotech products–even in the absence of scientific evidence that these foods pose a risk.

As chairman of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Basic Research of the Committee on Science, I held a series of three hearings, entitled “Plant Genome Research: From the Lab to the Field to the Market: Parts I-III.” Through these hearings and public meetings around the country, I examined plant genomics and its application to crops as well as the benefits, safety, and regulation of plant biotechnology.

What I found is that biotechnology has incredible potential to enhance nutrition, feed a growing world population, open up new markets for farmers, and reduce the environmental impact of farming. Crops designed to resist pests or tolerate herbicides, freezing temperatures, and drought will make agriculture more sustainable by reducing the use of synthetic chemicals and water as well as promoting no-tillage farming practices. These innovations will help protect the environment by reducing the pressure on current arable land.

Agricultural biotechnology also will be a key element in the fight against malnutrition worldwide. The merging of medical and agricultural biotechnology will open up new ways to develop plant varieties with characteristics that enhance health. For example, work is underway to deliver medicines and edible vaccines through common foods that could be used to immunize individuals against infectious diseases.

Set against these many benefits are the hypothetical risks of agricultural biotechnology. The weight of the scientific evidence indicates that plants developed with biotechnology are not inherently different or more risky than similar products of conventional breeding. In fact, modern biotechnology is so precise, and so much more is known about the changes being made, that plants produced with this technology may be safer than traditionally bred plants.

This is not to say that there are no risks associated with biotech plants, but that these risks are no different than those for similar plants bred using traditional methods, a view that has been endorsed in reports by many prestigious national and international scientific and governmental bodies, including the most recent report by the National Academy of Sciences. These reports have reached the common-sense conclusion that regulation should focus on the characteristics of the plant, not on the genetic method used to produce it.

I will continue to work in Washington to ensure that consumers enjoy the benefits of biotechnology while being protected by appropriate science-based regulations.

REP. NICK SMITH

Republican of Michigan

Chairman of the U.S. House Subcommittee on Basic Research

His report, Seeds of Opportunity, is available at http://www.ask-force.org/web/Regulation/Smith-Seeds-Opportunity2000.pdf

Henry I. Miller and Gregory Conko make a very persuasive case that ill-advised UN regulatory processes being urged on developing countries will likely stifle efforts to help feed these populations.

Just when the biotech industry seems to be waking up to the social and public relations benefits of increasing their scientific efforts toward indigenous crops such as cassava and other food staples, even though this is largely a commercially unprofitable undertaking, along comes a regulatory minefield that will discourage all but the most determined company.

Imagine the “truth in packaging” result if the UN were to declare: We have decided that even though cassava virus is robbing the public of badly needed food crops in Africa and elsewhere, we believe that the scarce resources of those countries are more wisely directed to a multihurdle regulatory approach. Although this may ensure that cassava remains virus-infected and people remain undernourished or die, it will be from “natural” causes–namely, not enough to eat–rather than “unnatural” risks from genetically modified crops.

We need to redouble efforts to stop highly arbitrary efforts designed to stifle progress. Perhaps then we can finally get down to science-based biotech regulation and policy around the world.

RICHARD J. MAHONEY

Distinguished Executive in Residence

Center for the Study of American Business

Washington University

St. Louis, Missouri

Former chairman of Monsanto Company

Henry Miller and Gregory Conko are seasoned advocates whose views deserve careful consideration. It is regrettable that they take a disputatious tone in their piece about biotechnology. Their challenging approach creates more conflict than consensus and does little to move the debate about genetically modified organisms (GMOs) toward resolution. This is unfortunate because there is much truth in their argument that this technology holds great promise to improve human and environmental health.

As they point out, the rancor over GMOs is intertwined with the equally contentious debate over the precautionary principle. They voice frustration that the precautionary principle gives rise to “poorly conceived, discriminatory rules” and “is inherently biased against change and therefore innovation.”

But while Miller and Conko invoke rational sound science in arguing for biotechnology, there is also science that gives us some idea of why people subconsciously “decide” what to be afraid of and how afraid to be. Risk perception, as this field is known, reveals much about why we are frequently afraid of new technologies, among other risks. An understanding of the psychological roots of precaution might advance the discussion and allow for progress on issues, such as biotechnology, where the precautionary principle is being invoked.

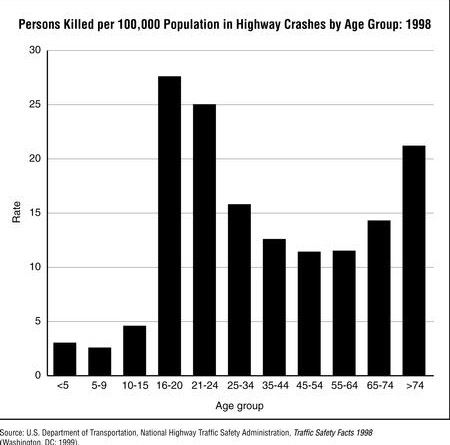

Pioneered by Paul Slovic, Vince Covello, and Baruch Fischoff, among others, risk perception posits that emotions and values shape our fears at least as much as, and probably more than, the facts. It offers a scientific explanation for why the fears of the general public often don’t match the actual statistical risks–for why we are more afraid of flying than driving, for example, or more afraid of exposure to hazardous waste than to fossil fuel emissions.

Risk perception studies have identified more than a dozen factors that seem to drive most of us to fear the same things, for the same reasons. Fear of risks imposed on us, such as food with potentially harmful ingredients not listed on the label, is often greater than fear of risks we voluntarily assume, such as eating high-fat foods with the fat content clearly posted. Another common risk perception factor is the quality of familiarity. We are generally more afraid of a new and little-understood hazard, such as cell phones, than one with which we have become familiar, such as microwaves.

Evidence of universal patterns to our fears, from an admittedly young and imprecise social science, suggests that we are, as a species, predisposed to be precautionary. Findings from another field support this idea. Cognitive neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux of New York University has found in test rats that external stimuli that might represent danger go to the ancient part of the animals’ brain and trigger biochemical responses before that same signal is sent on to the cortex, the thinking part of the brain. A few critical milliseconds before the thinking brain sends out its analysis of the threat information, the rest of the brain is already beginning to respond. Mammals are apparently biologically hardwired to fear first and think second.

Coupling this research with the findings of risk perception, it is not a leap to suggest that this is similar to the way we respond to new technologies that pose uncertain risks. This is not to impugn the precautionary principle as irrational because it is a response to risk not entirely based on the facts. To the contrary, this synthesis argues that the innate human desire for precaution is ultimately rational, if that word is defined as taking into account what we know and how we feel and coming up with what makes sense.

One might ask, “If we’ve been innately precautionary all along, why this new push for the precautionary principle?” The proposal of a principle is indeed new, inspired first in Europe by controversies over dioxin and mad cow disease and now resonating globally in a world that people believe is riskier than it’s ever been. But we have been precautionary for a long time. Regulations to protect the environment, food, and drugs and to deal with highway safety, air travel, and many more hazards have long been driven by a better safe than sorry attitude. Proponents of the principle have merely suggested over the past few years that we embody this approach in overarching, legally binding language. Precaution is an innate part of who we are as creatures with an ingrained survival imperative.

This letter is not an argument for or against the precautionary principle. It is an explanation of one way to understand the roots of such an approach to risk, in the hope that such an understanding can move the debate over the principle, and the risk issues wrapped up in that debate, forward. Biologically innate precaution cannot be rejected simply because it is not based on sound science. It is part of who we are, no less than our ability to reason, and must be a part of how we arrive at wise, informed, flexible policies to deal with the risks we face.

DAVID P. ROPEIK

Director, Rick Communication

Harvard Center for Risk Communication

Boston, Massachusetts

[email protected]

Because of biotechnology, agriculture has the potential to make another leap toward greater productivity while reducing dependency on pesticides and protecting the natural resource base. More people will benefit from cheaper safer food and value will be added to traditional agricultural commodities, but there will inevitably be winners and losers, further privatization of agricultural research, and further concentration of the food and agriculture sectors of the economy. Groups resisting changes in agriculture are based in well-fed countries that promote various forms of organic farming or seek to protect current market advantages.

When gene-spliced [recombinant DNA (rDNA)-modified] crops are singled out for burdensome regulations, investors become wary, small companies likely to produce new innovations are left behind, and the public is led to believe that all these regulations surely must mean that biotechnology is dangerous. Mandatory labeling has the additional effect of promoting discrimination against these foods in the supermarket.

In defense of the U.S. federal regulatory agencies, they have become a virtual firewall between the biotechnology industry, which serves food and agriculture, and a network of nongovernmental agencies and organic advocates determined to prevent the use of biotechnology in food and agriculture.

The real casualty of regulation by politics is science. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is about to finalize a rule that will subject genes and their biochemical products (referred to as “plant-incorporated protectants”) to regulation as pesticides when deployed for pest control, although this has been done safely for decades through plant breeding. The rule singles out for regulation genes transferred by rDNA methods while exempting the same genes transferred by conventional breeding. This ignores a landmark 1987 white paper produced by the National Academy of Sciences, which concluded that risk should be assessed on the basis of the nature of the product and not the process used to produce it.

The EPA’s attempt at a scientific explanation for the exemption is moot, because few if any of the “plant-incorporated protectants” in crops produced by conventional plant breeding are known, and they therefore cannot be regulated.

Henry Miller and Gregory Conko correctly point out that, “because gene-splicing is more precise and predictable than older techniques . . . such as cross breeding or induced mutagenesis, it is at least as safe.” Singling out rDNA-modified pest-protected crops for regulation is not in society’s long-term interests. Furthermore, many other countries follow the U.S. lead in developing their own regulations, which is all the more reason to do what is right.

R. JAMES COOK

Washington State University

Pullman, Washington

[email protected]

Eliminating tuberculosis

Morton N. Swartz eloquently states the critical importance of taking decisive action to eliminate tuberculosis (TB) from the United States (“Eliminating Tuberculosis: Opportunity Knocks Twice,” Issues, Fall 2000). On the basis of the May 2000 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Ending Neglect, Swartz calls for new control measures and increased research to develop better tools to fight this disease. He correctly points out the “global face” of TB and the need to engage other nations in TB control efforts. We would like to emphasize the need to address TB as a global rather than a U.S.-specific problem.

The CDC reports that there were 17,528 cases of TB in the United States in 1999, but the most recent global estimates indicate that there were 7.96 million cases of TB in 1997 and 1.87 million deaths, not including those of HIV-infected individuals. TB is the leading cause of death in HIV-infected individuals worldwide; if one includes these individuals in the calculation, the total annual deaths from TB are close to 3 million. Elimination of TB from the United States and globally will require improved tools for diagnosis of TB, particularly of latent infection; more effective drugs to shorten and simplify current regimens and control drug-resistant strains; and most important in the long term, improved vaccines. As one of us (Anthony Fauci) recently underscored in an address at the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s 38th Annual Meeting (on September 7, 2000 in New Orleans), the development of new tools for infectious disease control in the 21st century will build on past successes but will incorporate many exciting new advances in genomics, proteomics, information technology, synthetic chemistry, robotics and high-throughput screening, mathematical modeling, and molecular and genetic epidemiology.

In March 1998, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Vaccine Program Office, and the Advisory Council for the Elimination of Tuberculosis cosponsored a workshop that resulted in the development of a “Blueprint for TB Vaccine Development.” NIAID is moving, as Ending Neglect recommended, to implement this plan fully, in cooperation with interested partners. On May 22 and 23, 2000, NIAID hosted the first in a series of meetings in response to President Clinton’s Millennium Vaccine Initiative, aimed at addressing the scientific and technical hurdles facing developers of vaccines for TB, HIV/AIDS, and malaria, and at stimulating effective public-private partnerships devoted to developing these vaccines. On October 26 and 27, 2000, NIAID convened a summit of government, academic, industrial, and private partners to address similar issues with regard to the development of drugs for TB, HIV/AIDS, and other antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. Based on recommendations from these and many other sources, NIAID, in partnership with high-burden countries and other interested organizations, is currently formulating a 10-year plan for global health research in TB, HIV/AIDS, and malaria. This plan will include initiatives for the development of new tools suited to the needs of high-burden countries and for the establishment of significant sustainable infrastructure for research in these most-affected areas.

We agree with Swartz and the IOM report that now is the time to eliminate TB as a public health problem. We stress that in order to be effective and responsible, such an elimination program must include a strong research base to develop the required new tools and must occur in the context of the global epidemic.

ANN GINSBERG

ANTHONY S. FAUCI

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Bethesda, Maryland

Morton N. Swartz’s article supports the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) warning that we are at “a crossroads in TB control.” It can be a future of expanded use of effective treatment and the reversal of an epidemic, or a future in which multi-drug-resistant TB increases and millions more become ill.

Most Americans think of TB as a disease that has all but been defeated. However, WHO estimates that if left unchecked, TB could kill more than 70 million people around the world in the next two decades, while simultaneously infecting nearly one billion more.

The implications for third-world nations are staggering. TB is both the product and a major cause of poverty. Poor living conditions and lack of access to proper treatment kill parents. When TB sickens or kills the breadwinner in a family, it pushes the family into poverty. It’s a vicious cycle.

This isn’t just a problem for the developing world. TB can be spread just by coughing, and with international travel, none of us are safe from it. Poorly treated TB cases in countries with inadequate health care systems lead to drug-resistant strains that are finding their way across the borders of industrialized countries. Unless we act now, we risk the emergence of TB strains that even our most modern medicines can’t combat.

The most cost-effective way to save millions of lives and “turn off the tap” of drug-resistant TB is to implement “directly observed treatment, shortcourse” (DOTS), a cheap and effective program that monitors a patient’s drug courses for an entire phase of treatment. The World Bank calls DOTS one of the most cost-effective health interventions available, producing cure rates of up to 95 percent in the poorest countries. Unfortunately, effective DOTS programs are reaching fewer than one in five of those ill with TB worldwide.

The problem is not that we are awaiting a miracle cure or that we can’t afford to treat the disease globally. Gro Brundtland, the director general of WHO, has said that “our greatest challenges in controlling TB are political rather than medical.”

TB is a national and international threat, and if we are going to eradicate it, we have to treat it that way. This means mobilizing the international community to fund DOTS programs on the ground in developing counties. It means convincing industrialized and third-world nations that it is in their best interests to eradicate TB.

TB specialists estimate that it will require a worldwide investment of at least an additional $1 billion to reach those who currently lack access to quality TB control programs. Congress must demonstrate our commitment to leading other donor nations to help developing nations battle this disease. That’s why I have introduced the STOP TB NOW Act, a bill calling for a U.S. investment of $100 million in international TB control in 2001. At this funding level, we can lead the effort and ensure an investment that will protect us all.

REP. SHERROD BROWN

Democrat of Ohio

The American Lung Association (ALA) is pleased to support the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Ending Neglect: The Elimination of Tuberculosis in the U.S. The ALA was founded in 1904 as the National Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis. Its mission, at that time, was the elimination of TB through public education and public policy. The ALA’s involvement with organized TB control efforts in the United States began before the U.S. Public Health Service or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were created. In 1904, TB was a widespread, devastating, incurable disease. In the decades since, tremendous advances in science and our public health system have made TB preventable, treatable, and curable. But TB is still with us. Our neglect of this age-old disease and the public health infrastructure needed to control it had a significant price: the resurgence of TB in the mid-1980s.

Morton N. Swartz, as chair of the IOM committee, raises a key question: “Will the U.S. allow another cycle of neglect to begin or instead will we take decisive action to eliminate TB?” The answer is found, in part, in a report by another respected institution, the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO’s Ad Hoc Committee on the Global TB Epidemic declared that the lack of political will and commitment at all levels of governments is a fundamental constraint on sustained progress in the control of TB in much of the world. In fact, the WHO committee found that the political and managerial challenges preventing the control of TB may be far greater than the medical or scientific challenges.

The recommendations of the IOM committee represent more than scientific, medical, or public health challenges. The CDC estimates that $528 million will be needed in fiscal year 2002 to begin fully implementing the IOM recommendations in the United States alone; a fourfold increase in current resources. Thus, the true challenge before us is how to create and sustain the political will critical to securing the resources needed to eliminate TB in this country, once and for all.

Throughout its history, the ALA has served as the conscience of Congress, state houses, and city governments, urging policymakers to adequately fund programs to combat TB. We will continue those efforts by seeking to secure the resources needed to fully implement the IOM report. We are joined in this current campaign by the 80-plus members of the National Coalition to Eliminate Tuberculosis. Swartz concluded his comments by recognizing the need for this coalition and its members to build public and political support for TB control.

As the scientific, medical, and public health communities (including the ALA) work to meet the challenges presented in the landmark IOM report, so must our policymakers. Truly ending the neglect of TB first takes the political will to tackle the problem. Everything else will be built on that foundation.

JOHN R. GARRISON

Chief Executive Officer

American Lung Association

New York, New York

Suburban decline

In “Suburban Decline: The Next Urban Crisis” (Issues, Fall 2000), William H. Lucy and David L. Phillips raise an important point. “Aesthetic charm,” as they refer to it, is all too often ignored when evaluating suburban neighborhoods. Although charm hardly guarantees that a neighborhood will remain viable, it does mean that, all things (schools, security, and property values) being equal, a charming neighborhood has a fair chance of being well maintained by successive generations of homeowners.

However, Lucy and Phillips do not pursue the logic of their insight. Generally speaking, middle-class neighborhoods built before 1945 have quality; postwar middle-class neighborhoods (and working-class neighborhoods of almost any vintage) don’t. Small lots, unimaginative street layouts, and flimsy construction do not encourage reinvestment, especially if alternatives are available. The other advantage of older suburbs is that they often contain a mixture of housing types whose diversity is more adaptable to changing market demands. Unfortunately, the vast majority of suburbs constructed between 1945 and 1970 are charmless monocultures. Of course, where housing demand is sufficiently strong, these sow’s ears will be turned into silk purses, but in weak markets homebuyers will seek other alternatives. In the latter cases, it is unlikely that the expensive policies that Lucy and Phillips suggest will arrest suburban decline.

WITOLD RYBCYNSKI

Graduate School of Fine Arts

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

[email protected]

Suburban decline may take awhile to become the next urban crisis, but William H. Lucy and David L. Phillips have spotlighted a serious societal issue. Some suburbs, particularly many built in the 25 years after World War II, have aged to the point where they are showing classic signs of urban decline: deteriorating real estate, disinvestment, lower-income residents, and social problems.

Suburban decline has yet to receive much attention beyond jurisdictions where it is an urgent problem. Hopefully, the work of Lucy and Phillips will open eyes. But even with recognition, I wonder what will be done.

The authors note that Canada and European countries have public policies that serve to minimize the deterioration of middle-aged suburbs (and old central cities). It’s done through centralized governmental planning and strong land use controls, coupled with an intense commitment to maintenance and redevelopment of built places. As a result, cities, towns, and the countryside in Canada and Europe look very different from their U.S. counterparts.

Most of America is a long, long way from European-style governmental controls. Oregon, with its growth boundaries and policies that promote maximum use of previously built places, is an extreme exception. Our philosophy of government places the decisions that affect the fate of communities at the state and local levels. Emphasis is on local control and property rights. That translates into local freedom to develop without intrusion from higher-level government. The same freedom also means that dealing with decline is a local responsibility.

Independent, fragmented local governments are severely limited in their capacity to overcome decline when they are enmeshed in a metropolitan area where free-rein development at the outer edges sucks the life from the urban core. In that situation combating decline is like going up an accelerating down staircase. Big central cities have been in that position for decades; now it’s the suburbs’ turn. Until states come to grips, as Oregon did, with the underlying factors that crucified the big cities and are beginning to do the same to suburbs, suburban decline will deepen and spread. Urban decline will continue as well (a few revitalized downtowns and neighborhoods disguise the continuing distress of cities).

For those engaged with the future of cities, suburban decline is a blessing because it might trigger new political forces. Some mayors of declining suburbs don’t like what is happening; they don’t like the fact that their state government crows about the new highway interchange 20 miles out in the countryside and the economic development that will occur there as a result (development that will be fed in part by movers from declining suburbs), while at the same time saying, in effect, to urban core communities: “Yes, we see your problems, your obsolete real estate, your crumbling sewer system, your school buildings that need extensive repairs. We feel your pain. But those are your problems. We wish you well. And by the way, the future is 20 miles out.”

If those mayors were to unite with other interests that are at stake in the urban core and fight back together, change in public policy, as advocated by Lucy and Phillips, could begin to happen. Calling attention to the problem as they are doing paves the way.

THOMAS BIER

Director

Housing Policy Research Program

Levin College of Urban Affairs

Cleveland State University

Cleveland, Ohio

[email protected]

William H. Lucy and David L. Phillips are quite right: There is decline in the inner-ring suburbs. But I’m not sure it is as dire as they suggest, for at least three reasons.

First, many of these communities have benefited from a growing economy during the 1990s, and we are not yet able to establish whether their decline has continued or abated during this prosperous decade, when incomes have risen for many Americans both inside and outside the center city limits. We must await the 2000 Census results. Having visited a goodly number of these suburbs, from Lansdowne, Penn., to Alameda, Calif., my hunch is that the deterioration will not be as steep as Lucy and Phillips imply.

Second, is the aging of housing stock close to the big city as significant a deterrent to reinvestment as the article suggests? The real estate mantra is “location, location, location.” This post-World War II housing has value because of where it is, not what it is. Furthermore, it seems to me that in many instances, people want the property more than the house that is on it, judging by the teardowns that can be observed in these close-in jurisdictions.

And third, we ought not underestimate the resilience of these places. The 1950s are history, but the communities built in those post-World War II days still stand, flexible and adaptable. Although the white nuclear family may be disappearing as their centerpiece, different kinds of families and lifestyles may be moving on to center stage. Singles, gays, working mothers, immigrants, empty nesters, home business operators, minorities, young couples looking for starter homes–all are finding housing in these suburbs, possibly remodeling it, and contributing to their revitalization. As Michael Pollan, author of A Place of My Own has written, these suburbs are being “remodeled by the press of history.”

Having said all this, the fact still remains that these “declining” suburbs need help, and Lucy and Phillips make a helpful suggestion. States really need to become more involved in promoting (sub-)urban revitalization, and the establishment of a Sustainable Region Incentive Fund at the state level could encourage local governments to work toward the achievement of the goals outlined in the article. The bottom line would be to reward good behavior with more funds for promoting reinvestment in these post-World War II bedroom communities.

Now, if only the states would listen!

WILLIAM H. HUDNUT, III

Senior Resident Fellow

Joseph C. Canizaro Chair for Public Policy

The Urban Land Institute

Washington, D.C.

As a lobbyist for 38 core cities and inner-ring suburban communities, I found William H. Lucy and David L. Phillips’ article to be a breath of fresh air. It constantly amazes me that with all our history of urban decline, some local officials still believe they can turn the tide within their own borders, and federal and state legislatures are content to let them try.

As we watch wealth begin to depart old suburbs for the new suburbs, we still somehow hope there will be no consequences of our inaction. I wonder when the light bulb will go on. It is the concentration of race and poverty and the segregation of incomes that drives the process. We say we want well-educated citizens with diplomas and degrees, but housing segregated along racial and income lines makes it more difficult to achieve our goals. And segregated housing has been the policy of government for decades.

Strategies for overcoming this American Apartheid are many, and the battleground will be in every state legislature. There needs to be bipartisan political will to change. The issues before us are neither Republican nor Democrat. Everyone in society must commit to living with people of different incomes and race. State government must make this accommodation easier.

We need: 1) Strong statewide land use planning goals that local government must meet. 2) Significant state earned income tax credits for our working poor. 3) Growth boundaries for cities and villages. 4) New mixed-income housing in every neighborhood. 5) Regional governmental approaches to transportation, economic development, job training, and local government service delivery. 6) Regional tax base sharing. 7) State property tax equalization programs for K-12 education and local governments. 8) Grants and loans for improving old housing stock.

In the end, it is private investment that will change the face of core cities and inner-ring suburbs. But that investment needs to be planned and guided to ensure that development occurs in places that have the infrastructure and the people to play a role in a new and rapidly changing economy. The local government of the future depends on partnership with state government.

We live in a fast-changing 21st century that depends on the service delivery and financing structures we inherited from 19th-century local government. The challenge is before us, thanks to efforts such as the Lucy/Phillips article. What is our response? Only time will tell.

EDWARD J. HUCK

Executive Director

Wisconsin Alliance of Cities

Madison, Wisconsin

Postdoctoral training

Maxine Singer’s “Enhancing the Postdoctoral Experience” (Issues, Fall 2000) provides a cogent assessment of a key component of the biomedical enterprise: the postdoc. At the National Institutes of Health (NIH) we firmly support the concept that a postdoctoral experience is a period of apprenticeship and that the primary focus should be on the acquisition of new skills and knowledge necessary to advance professionally. There is clear value in having the supervisor/advisor establish an agreement with the postdoc at the time of appointment about the duration of the period of support, the nature of the benefits, the availability of opportunities for career enhancement, and the schedule of formal performance evaluations. Many of these features have been available to postdocs in the NIH Intramural Programs and to individuals supported by National Research Service Award (NRSA) training grants and fellowships. NIH has never, however, established similar guidelines for postdocs supported by NIH research grants. We’ve always relied on the awardee institution to ensure that all individuals supported by NIH awards were treated according to the highest standards. Although most postdocs probably receive excellent training, it may be beneficial to formally endorse some of the principles in Singer’s article.

The other issue raised by Singer relates to emoluments provided to extramurally supported postdocs. NIH recognized that stipends under NRSA were too low and adjusted them upward by 25 percent in fiscal 1998. Since 1998, we’ve incorporated annual cost-of-living adjustments to keep up with inflation. It is entirely possible that NRSA stipends need another large adjustment and we’ve been talking about ways to collect data that might inform this type of change. Because many trainees and fellows are married by the time they complete their training, we started offering an offset for the cost of family health insurance in fiscal 1999. Compensation has to reflect the real life circumstances of postdocs.

Singer also raises concerns about the difficulty many postdocs report as they try to move to their first permanent research position. In recognition of this problem, many of the NIH institutes have started to offer Career Transition Awards (http://grants.nih.gov/training/careerdevelopmentawards.htm. Although there are differences in the nature of these awards, the most important feature is that an applicant submits an application without an institutional affiliation. Then, if the application is determined to have sufficient scientific merit by a panel of peer reviewers, a provisional award can be made for activation when the candidate identifies a suitable research position. The award then provides salary and research support for the startup years. Many postdocs have found these awards attractive, and we hope in the near future to identify transitional models that work and to expand their availability.

Undoubtedly, NIH can do more and discussions of these issues are under way. We hope that NIH, at a minimum, can begin to articulate our expectations for graduate and postdoctoral training experiences.

WENDY BALDWIN

Deputy Director for Extramural Research

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

For at least the past 10 years there has been concern about the difficult situation of postdoctoral scholars in U.S. academic institutions. The recent report of the Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP) describes these concerns, principally regarding compensation and benefits, status and recognition, educational and mentoring opportunities, and future employment options. I commend COSEPUP for the thoroughness of their study and for their compilation of a considerable amount of qualitative information on the conditions of postdoctoral appointments and on postdocs’ reactions to those conditions.

Postdocs have become an integral part of the research enterprise in the United States. They provide cutting-edge knowledge of content and methods, they offer a fresh perspective on research problems, and they provide a high level of scholarship. And critically, as the COSEPUP report points out, postdocs have come to provide inexpensive skilled labor, compared with the alternatives of graduate students (who have less knowledge and experience and for whom tuition must be paid) and laboratory technicians or faculty members (who are more often permanent employees with full benefits). Not only are there strong economic incentives for universities to retain postdocs to help produce research results, there are not enough positions seen as desirable to lure postdocs out of their disadvantageous employment situations. These economic and employment factors taken together create strong forces for maintaining the status quo for postdocs.

The COSEPUP report raises our awareness of the problems, but it only begins to acknowledge the complexity and intractability of the situation. COSEPUP’s recommendations, although an excellent starting point for discussion, tend to oversimplify the problem. For example, for funding agencies to set postdoc stipend levels in research grants would require specifying assumptions about compensation levels across widely varying fields and geographic areas. Stipends for individual postdoctoral fellowships tend to vary across disciplines, just as do salaries. How should field variations be accommodated in setting minimum stipends for postdocs on research grants? What about cost-of-living considerations?

Many but not all of the COSEPUP recommendations would require additional money for the support of postdocs. Unless research budgets increase–and, of course, we continue to work toward that goal–additional financial support for postdocs would mean reductions in some other category. Perhaps that is necessary, but such decisions must be approached with great care.

One can safely assume that resources for research (or any other worthy endeavor) will never meet the full demand. COSEPUP has wisely identified another set of issues to be considered in the allocation of those resources, and COSEPUP has also indicated that a number of interrelated groups need to be involved in the discussions. Those of us in those groups need to be similarly wise in our interpretations of COSEPUP’s findings and our adaptation and implementation of their recommendations. We need balanced, well-reasoned actions on the part of all parties in order to construct solutions that fit the entire complex system of research and education.

SUSAN W. DUBY

Director, Division of Graduate Education

National Science Foundation

Arlington, Virginia

[email protected]

Science at the UN

In “The UN’s Role in the New Diplomacy” (Issues, Fall 2000), Calestous Juma raises a very important challenge of growing international significance: the need for better integration of science and technology advice into issues of international policy concern. This is a foreign policy challenge for all nations. The list of such issues continues to grow, and policy solutions are not simple. Among the issues are climate change and global warming, genetically modified organisms, medical ethics (in stem cell research, for example), transboundary water resource management, management of biodiversity, invasive species, disaster mitigation, and infectious diseases. The U.S. State Department, for example, has recognized this need and taken important steps with a policy directive issued earlier this year by the secretary of state that assigns greater priority to the integration of science and technology expertise into foreign policymaking. However, such efforts appear not to be common internationally, and success in any nation or forum will require determined attention by all interested parties.

The international science policy discussion is made more complex when information among nations is inconsistent or incomplete, or when scientific knowledge is biased or ignored to meet political ends. Greater clarity internationally regarding the state of scientific knowledge and its uncertainties can help to guide better policy and would mitigate the misrepresentation of scientific understanding. Tighter integration of international science advisory mechanisms such as the Inter-Academy Council is critical to bring together expertise from around the globe to strengthen the scientific input to policy, and to counteract assumptions of bias that are sometimes raised when views are expressed by any single nation. This is an issue that clearly warrants greater attention in international policy circles.

GERALD HANE

Assistant Director for International Strategy and Affairs

Office of Science and Technology Policy

Washington, D.C.

Coral reef organisms

In “New Threat to Coral Reefs: Trade in Coral Organisms” (Issues, Fall 2000) Andrew W. Bruckner makes many valid points regarding a subject that I have been concerned about for many years, even before the issues were raised that are now beginning to be addressed. There are over one million marine aquarists in America. Most of them feel that collection for the aquarium trade has at least some significant impact on coral reefs. Almost universally, their concern is expressed by a willingness to pay more for wild collected coral reef organisms if part of the selling price helps fund efforts in sustainable collection or coral reef conservation, and by a heavy demand for aquacultured or maricultured species.

Bruckner mentions several very real problems with the trade, including survivability issues under current collection practices. Most stem from the shortcomings of closed systems in meeting dietary requirements. Many species are widely known to survive poorly, yet continue to represent highly significant numbers of available species. Conversely, many that have excellent survival are not frequently available. Survivability depends, among other things, on reliable identification, collection methods, standards of care in transport and holding, individual species requirements (if known), the abilities and knowledge of the aquarist, and perhaps most disconcertingly, economics.

There are hundreds of coral species currently being cultured, both in situ and in aquaria, and the potential exists for virtually all species to be grown in such a fashion. Furthermore, dozens of fish species can be bred, with the potential for hundreds more to be bred or raised from postlarval stages. Yet the economics currently in place dictate that wild collected stock is cheaper, and therefore sustainably collected or cultured organisms cannot compete well in the marketplace. Furthermore, economics dictate that lower costs come with lower standards of care and hence lower survivability.

Aquaria are not without merit, however. Many of the techniques currently being used in mariculture and in coral reef restoration came from advances in the husbandry of species in private aquaria. Coral “farming” is almost entirely a product of aquarist efforts. Many new observations and descriptions of behaviors, interactions, physiology, biochemistry, and ecology have come from aquaria, a result of long-term continuous monitoring of controllable closed systems. Furthermore, aquaria promote exposure to and appreciation of coral reef life for those who view them.

Solutions to current problems may include regulation, resource management, economic incentive for sustainable and nondestructive collection, licensing and improving transport/holding facilities to ensure minimal care standards, improving the fundamental understanding of species requirements, and husbandry advancement. The collection of marine organisms for aquaria need not be a threat to coral reefs, but with proper guidance could be a no-impact industry, provide productive alternative economies to resource nations, and potentially become a net benefit to coral reefs. For this to become a reality, however, changes as suggested by Bruckner and others need to occur, especially as reefs come under increasing impacts from many anthropogenic sources.

ERIC BORNEMAN

Microcosm, Ltd.

Shelburne, Vermont

[email protected]

Science’s social role

Around 30 years ago, Shirley Williams, a well-known British politician, asserted in The Times that, for scientists, the party is over. She was referring to the beginning of a new type of relationship between science and society, in which science has lost its postwar autonomy and has to confront public scrutiny. This idea was used by Nature when reporting on the atmosphere you could feel at the recent World Conference on Science, organized by the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization and the International Council of Scientific Unions during June-July 1999, which gathered together in Budapest delegations from nearly 150 countries, as well as a large number of representatives of scientific organizations worldwide.

The phrase “social contract” was frequently used during the conference when discussing the “new commitment” of science in the 21st century: a new commitment in which science is supposed to become an instrument of welfare not only for the rich, the military, and scientists themselves but for society at large and particularly for those traditionally excluded from science’s benefits. When reading Robert Frodeman and Carl Mitcham’s “Beyond the Social Contract Myth” (Issues, Summer 2000), one has the feeling that they want the old party to be started again, although this time for a larger constituency. As I see it, this is not a realistic possibility and hardly a desirable one when considering contemporary science as an institution.

Yet, I am very sympathetic to the picture the authors present of the ideal relationship between science and society and of the ultimate goal that should move scientists: the common good. My problem with Frodeman and Mitcham’s argument concerns its practical viability for regulating the scientific institution in an effective manner, so as to trigger such a new commitment and direct science toward the real production of common good.

The viability of the language of common good depends on a major presupposition: trust. A familiar feature of contemporary science is its involvement in social debates on a broad diversity of subjects: the economy, sports, health, the environment, and so on. The social significance of science has transformed it into a strategic resource used by a variety of actors in the political arena. But this phenomenon has also undermined trust in expert advice (“regulatory science,” in the words of Sheila Jasanoff), in contrast to the trustful nature of traditional academic science.

A large array of negative social and environmental impacts, as well as the social activism of the 1960s and 70s, have contributed much to the lack of trust of science. Recent social revolts against globalization and the economic order, like the countercultural movement, have taken contemporary technoscience as a target of their criticism. In the underdeveloped nations, social confidence in science is also very meager, as in any institution that is linked to the establishment. And without trust between the parties, whether in the first or third world, an important presupposition of the language of common good is lacking.

I believe that the quest for the common good is an ideal that should be kept as part of the professional role of individual scientists and engineers. The promotion of this ethos could fulfill an important service for both science and society. However, when the discussion reaches actual policy and considerations turn to the setting of research priorities and the allocation of resources, the language of the social contract is much more appropriate to the reality of science as an institution and thus, eventually, to the prospects of realizing the new commitment dreamed of by most people in Budapest.

JOSÉ A. LOPEZ CEREZO

University of Oviedo, Spain

[email protected]

Robert Frodeman and Carl Mitcham are to be commended for raising what ought to be a fundamental issue in the philosophy of science. Alas, philosophers all too rarely discuss the nature and scope of the social responsibility of science.

I agree with Frodeman and Mitchell that a social contract model of scientific responsibility is not adequate, but I criticize both their interpretation of contractualism and their proposed alternative. The notion of a social contract between science and society has not previously been carefully articulated, so they rightly look to contractualist political thought as a model to give it content. Despite their suggestion that contract theories are now passe, however, such theories are currently the dominant theoretical approach within anglophone political thought. Moreover, contract theories hold this position because they have moved beyond the traditional assumptions that Frodeman and Mitcham challenge. So we need to reconsider what modern contract theories would have to say about science and society.

Contrary to Frodeman and Mitcham, contract theories nowadays do not posit real contracts or presuppose atomistic individuals. The problem they address is that the complex social ties and cultural conceptions within which human lives are meaningful are multiple and deeply conflicting. Since there is supposedly no noncoercive way of resolving these fundamental ethical differences to achieve a common conception of the good, contract theories propose to find more minimal common ground for a narrowly political community. A contract models political obligations to others who do not share one’s conception of the good; it thereby allows people to live different lives in different, albeit overlapping and interacting, moral communities, by constructing a basis for political authority that such communities can accept despite their differences.

Adapted to science and society, a contract model might be conceived as establishing a minimalist common basis for appropriate scientific conduct, given the substantial differences among conceptions of the sciences’ goals and obligations to society. In such a model, many social goods could and should be pursued through scientific work that is not obligated by the implicit contract. Many of these supposed goods conflict, however. A contract would model more narrowly scientific obligations, such as open discussion, empirical accountability, honesty and fairness in publication, appropriate relations with human and animal research subjects, safe handling and disposal of laboratory materials, conflicts of interest, and so forth. The many other ethical, social, and cultural goods addressed by scientific work would then be pursued according to researchers’ and/or their supporting institutions’ conceptions of the good, constrained only by these more limited scientific obligations.

The fundamental difficulties with such a model are twofold. First, it fails to acknowledge the pervasiveness and centrality of scientific work to the ways we live and the issues we confront. These cannot rightly be determined by “private” conceptions of the good, as if what is at stake in science beyond contractual obligations is merely a matter of individual or institutional self-determination. Frodeman and Mitcham are thus right in saying that we need a more comprehensive normative conception than a contract theory can provide. Second, it fails to acknowledge the ways in which social practices and institutions, including scientific practices, both exercise and accede to power in ways that need to be held accountable. Scientific communities and their social relations, and the material practices and achievements of scientific work, are both subject to and transformative of the power dynamics of contemporary life.

I do not have space here to articulate what would be a more adequate alternative that would simultaneously respond appropriately to fundamental ethical disagreement, the pervasive significance of scientific practices, and the complex power relations in which the sciences, engineering, and medicine are deeply entangled. Frodeman and Mitcham’s proposal, however, seems deeply problematic to me for their inattention to the first and last of these three considerations, even as they appropriately try to accommodate the far-reaching ways in which the sciences matter to us. They fail to adequately recognize the role of power and resistance in contemporary life, a failure exemplified in their idyllic but altogether unrealistic conception of professionalization. This oversight exacerbates their inattention to the underlying ethical and political conflicts that contract theories aim to address. To postulate a common good in the face of deep disagreement, while overlooking the power dynamics in which those disagreements are situated, too easily confers moral authority on political dominance.

Much better to recognize that even the best available courses of action will have many untoward consequences, and that some agents and institutions have more freedom to act and more ability to control the terms of public assessment. A more adequate politics would hold these agents and institutions accountable to dissenting concerns and voices, especially from those who are economically or politically marginalized; their concerns are all too often the ones discredited and sacrificed in the name of a supposedly common good. We thus need to go beyond both liberal contractualism and Frodeman and Mitcham’s communitarianism for an adequate political engagement with what is at stake in scientific work today. Whether one is talking about responses to global warming, infectious disease, nuclear weapons, nuclear waste, or possibilities for genetic intervention, we need a more inclusive and realistic politics of science, not because science is somehow bad or dangerous but precisely because science is important and consequential.

JOSEPH ROUSE

Department of Philosophy

Wesleyan University

Middletown, Connecticut

[email protected]

Scientific evidence in court

Donald Kennedy and Richard A. Merrill’s “Science and the Law” (Issues, Summer 2000) revisited for me the round of correspondence I had with National Academy of Engineering (NAE) President Wm. A. Wulf on the NAE’s position on the Supreme Court’s consideration of Kumho.

The NAE’s Amicus Curiae brief stressed applying Daubert’s Rule 702 on “scientific evidence” and the four factors of empirical testability, peer review and publication, rate of error of a technique, and its degree of acceptance to expert engineering testimony. The NAE brief concluded by urging “this Court to hold that Rule 702 requires a threshold determination of the relevance and reliability of all expert testimony, and that the Daubert factors may be applied to evaluate the admissibility of expert engineering testimony.”

In my September 22, 1998, letter to President Wulf, I took exception to the position the NAE had instructed its counsel to take. Since most of my consulting is in patent and tort litigation as an expert witness, I am quite familiar with Daubert, and when a case requires my services as a scientist, I have no problem with Daubert applied to a science question.

In my letter to Wulf I went on to say:

“But I ask you how would you, as an engineer, propose to apply these four principles to a case like Kumho v. Carmichael? No plaintiff nor their expert could possibly propose to test tires under conditions exactly like those prevailing at the reported accident and certainly the defendant, the tire manufacturer, would not choose to do so. But even if such tests could be conducted, what rate of error could you attest to, and how would you establish the degree of acceptance, and what role would you assert peer review or publication plays here (i.e., to what extent do tire manufacturers or putative tire testers publish in the peer-reviewed literature) etc.?

The issue here is not, as the NAE counsel was reported to have asserted, that engineering ‘is founded on scientific understanding’; of course it is! Rather, in addition to the issues in the above paragraph, it is that engineering is more than simply science or even, as it is sometimes caricatured, ‘applied science.’

In one of your recent letters to the membership, you yourself distinguished engineering from science, noting the constraints under which engineering must operate in addition to those dictated by nature–social, contextual, extant or anticipated real need, timeliness, financial, etc. And then there is the undermining of ‘the abilities of experts to testify based on their experience and knowledge.’ How are all of these to be recognized in the Daubert one-rule-of-testimony-serves-all-fields approach you and the NAE appear to be espousing?

And engineering alone is not at stake in your erroneous position, should the Supreme Court agree with your NAE counsel’s argument. As the lawyer for the plaintiff notes, applying the Daubert principles broadly, as is your position, will exclude from court testimony ‘literally thousands of areas of expertise,’ including those experts testifying in medical cases. Has the NAE checked its legal position with the IOM?”

Wulf’s May 7, 1999, “Dear Colleagues” (NAE) letter stated that, “I am happy to report that the Court unanimously agreed with us and cited our brief in its opinion!” I was disappointed but assumed that was the end of the issue; Wulf reported that the Court had spoken.

Now throughout the Issues article I read that the court’s position was not as perfectly aligned with the NAE’s brief as the president of the NAE led me and others to believe. To choose one such instance, on page 61 column one I read, “the Court now appears less interested in a taxonomy of expertise; it points out that the Daubert factors ‘do not necessarily apply even in every instance in which the reliability of scientific testimony is challenged.’ The Kumho Court contemplates there will be witnesses ‘whose expertise is based only on experience,’ and although it suggests that Daubert’s questions may be helpful in evaluating experience-based testimony, it does not, as in Daubert, stress testability as the preeminent factor of concern.”

I thank Issues for bringing to closure what had been for me a troubling issue.

ROBERT W. MANN

Whitaker Professor Emeritus

Biomedical Engineering

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

[email protected]

Lawrence Lessig’s book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace begins and ends with two key themes: that our world is increasingly governed by written code in the form of software and law and that the code we are creating is decreasingly in the service of democratic objectives. Linked to these themes is a broad array of issues, including the architecture of social control, the peculiarities of cyberspace, the problems of intellectual property, the assault on personal privacy, the limits of free speech, and the challenge to sovereignty. The book is compelling and disturbing. It is a must-read for those who believe that the information revolution really is a revolution.

Lawrence Lessig’s book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace begins and ends with two key themes: that our world is increasingly governed by written code in the form of software and law and that the code we are creating is decreasingly in the service of democratic objectives. Linked to these themes is a broad array of issues, including the architecture of social control, the peculiarities of cyberspace, the problems of intellectual property, the assault on personal privacy, the limits of free speech, and the challenge to sovereignty. The book is compelling and disturbing. It is a must-read for those who believe that the information revolution really is a revolution. The Ingenuity Gap is about how to worry efficiently in the 21st century. Most people worry inefficiently, either with undifferentiated anxiety about an unknown future or with hypomania about unprioritized details. This book focuses on what’s going right and is likely to get better in the future–science and technology–and on what’s likely to be the fulcrum of our weaknesses–social systems.

The Ingenuity Gap is about how to worry efficiently in the 21st century. Most people worry inefficiently, either with undifferentiated anxiety about an unknown future or with hypomania about unprioritized details. This book focuses on what’s going right and is likely to get better in the future–science and technology–and on what’s likely to be the fulcrum of our weaknesses–social systems. Laurie Garrett, author of The Coming Plague and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for her reporting of the 1995 outbreak of the Ebola virus in Zaire, has been an important voice for those who advocate the need for increased attention to global public health. In her new book, Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health, Garrett takes the reader on a journey across place and time to make the case that public health worldwide is dying, if not already dead. And she warns us of the dire consequences–the reemergence of deadly infectious diseases, the growing potential for biologic terrorism, and the weakening of global disease surveillance and response capabilities, among others–that await us all, rich and poor, young and old, as a result.

Laurie Garrett, author of The Coming Plague and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for her reporting of the 1995 outbreak of the Ebola virus in Zaire, has been an important voice for those who advocate the need for increased attention to global public health. In her new book, Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health, Garrett takes the reader on a journey across place and time to make the case that public health worldwide is dying, if not already dead. And she warns us of the dire consequences–the reemergence of deadly infectious diseases, the growing potential for biologic terrorism, and the weakening of global disease surveillance and response capabilities, among others–that await us all, rich and poor, young and old, as a result.