Controlling health care costs

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote, “These are my politics: to change what we can; to better what we can.” Health care in the 21st century requires a change from old ways of thinking and doing business to better the lives of all Americans.

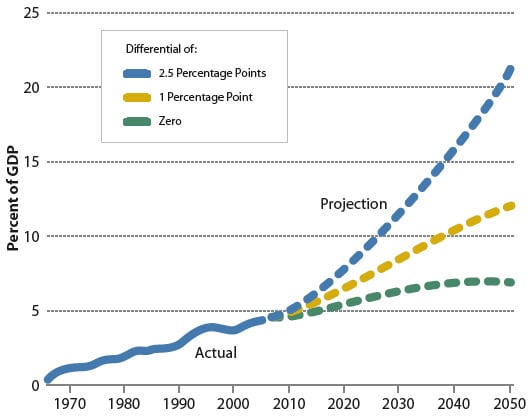

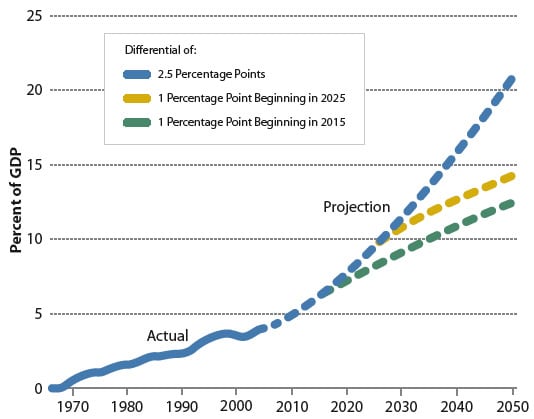

The articles by Peter Orszag (“Time to Act on Health Care Costs”) and Elliott S. Fisher (”Learning to Deliver Better Health Care”) in the Spring 2008 Issues are just two of the growing number of articles discussing the broken health care system in America. Orszag reports that the runaway costs of the Medicare program are attributed to the rising costs per beneficiary, not solely to the increasing numbers of older adults. Fisher rightly states that this increased cost, due to more frequent physician visits and hospitalizations, referrals to multiple specialists, and frequent use of advanced imaging services, varies across the country and does not better the lives of patients. Perversely, higher spending seems to lead to less satisfaction with care and worse health outcomes.

Fortunately, it is possible to improve the health of individuals, families, and communities while controlling costs. Congress is acting to immediately introduce legislation to improve the care that Medicare beneficiaries receive. For example, it is my hope that Medicare legislation that Congress intends to pass this year will include policies to improve the quality of care patients receive and increase access to health promotion and disease prevention services. Further, the Senate Committee on Finance has set an aggressive agenda of hearings this year to identify additional strategies for health care reform. As part of this series, on June 16, we will convene a full-day Health Summit to bring together health care leaders and Congress to explore viable strategies to improve the health of Americans.

The demand for health care reform goes beyond Medicare and Medicaid. The overall quality and cost of care must be addressed. Public and private payment systems can be tools used to obtain more appropriate health care while controlling costs. Payment should support clinical decisions based on the best available evidence, instead of irregular local practices. The judicious and appropriate use of technology will improve the lives of Americans and stimulate innovation. Because approximately three-fourths of the health care dollar goes to treating the complications of chronic illness, preventing disease and carefully managing chronic conditions are vital, and we should target the most expensive medical conditions first.

In the 16th century, Richard Hooker wrote, “Change is not made without inconvenience, even from worse to better.” This remains true in the 21st century. We know what needs to be done and how to do it. We have the political will to make the necessary changes. It will require continued commitment from all health care providers and payers to meet the expectations of the American public.

Senator Max Baucus

Democrat of Montana

When it comes to health care, we all want the best. We want the latest, most sophisticated care for ourselves and our loved ones. We want the steady, unencumbered march of medical innovation that will bring us tomorrow’s treatments, cures, and preventions. And we want this high-quality, accessible, and forwardmoving care at a fair and sensible price. Once a year, most Americans make a price-driven decision about our choice of health insurance. Throughout the rest of the year, we don’t want money to be a factor in the decisions made about our care.

WE NEED TO EMBRACE WELL-DESIGNED PAY-FOR-PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS THAT PROVIDE APPROPRIATE INCENTIVES TO DO THE RIGHT THING FOR PATIENTS, BUT NO MORE OR LESS.

The articles by Peter Orszag and Elliot S. Fisher present thoughtful perspectives in the ongoing debate about medical costs, quality, and access. The authors note the significant variations in health care costs and practices across different regions of the country and point out that certain higher-cost practices do not necessarily translate into better outcomes. They advocate for a system that balances care, efficiency, and costs in part by identifying best practices, sharing them openly, and embracing them willingly. Orszag also demonstrates that the aging of our population is likely to drive inexorable increases in our society’s health care spending.

Health care providers should clearly look to one another to share practices that make the most sense for patients and for society. We need to rigorously study and analyze promising ideas and methods that can bring greater value to our health care system, and we need to adopt these best practices widely and universally. Controlling health care costs will also require stronger effectiveness reviews of drugs, devices, and technology to evaluate whether new products are a good value and what their reimbursement should be. The recent widespread dissemination of the da Vinci robot is a good case study about the consequences of the absence of such a review system. Implementing electronic medical records and expanding information systems that enhance care coordination among providers and support clinical decisions also offer great cost-saving potential. Another important tool in cost control is process improvement, which identifies unnecessary steps and removes waste from the system while enhancing quality and safety.

Adopting best practices and injecting more uniformity into health care should help curb health care costs, but this approach won’t work in isolation. We also must take a hard look at payment reform. It is important, for instance, to find ways to reward those who practice evidence-based medicine, those who offer effective disease management programs and those who provide ongoing preventive care. In addition, we need to embrace well-designed pay-for-performance programs that provide appropriate incentives to do the right thing for patients, but no more or less.

The road leading to high-quality care, ongoing innovation, and cost control is long and winding. But given the national attention to these issues, now is the time to make choices and decisions. We must act quickly as a nation to develop the necessary policies and programs to do so. Doing so may allow us to trim the unnecessary fat in our health care system and not be forced to cut into the muscle.

PETER L. SLAVIN

President

Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

Peter Orszag suggests that the United States could reduce growth in health care costs by pruning low-hanging fruit— unwarranted variation—from the invasive vines of health care spending.

For more than 30 years, John Wennberg, Elliott Fisher, and colleagues at Dartmouth have documented remarkable regional variations in Medicare spending across the United States. Dartmouth Atlas research has shown that the quality of care is actually worse when spending and use of care (more visits and tests) are greater. Fisher says that if all U.S. regions would safely adopt the organizational structures and practice patterns of the lowest-spending regions, Medicare spending would decline by about 30%.

This demonstrates a tremendous opportunity for providers to improve quality and decrease health care costs; in other words, to increase the value of the care we provide to patients. Here are two ways to move the health care industry in that direction.

Coordinate care. Traditionally, physicians have been trained in a competitive environment that rewards knowledge and independence. Yet we know that the highest-value care is delivered in regions where providers work in teams in various organizational models. Patients, particularly those with chronic or complex illnesses, need and deserve coordinated care, in which physicians are team members, working as partners with patients, families, nurses, and other health care professionals.

Pay for value. Because our current reimbursement system rewards piecework (more reimbursement for performing more visits, diagnostic tests, and procedures), it’s natural that U.S. health care is laden with it. To get the value we want, payers should begin to reward those who deliver high-quality care at a lower cost over time. Currently, physicians who offer efficient high-quality care are financially penalized. In addition, our current system does not reward providers who offer coordination of care for patients, who often do not need a physical visit to the doctor’s office.

Orszag suggests that moving from a fee-for-service to a fee-for-value system, in which higher-value care is rewarded with stronger financial incentives could yield the largest long-term budgetary gains. Fortunately, some standardized data, including the Dartmouth Atlas (measuring cost) and the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review File (measuring mortality), are now publicly available. In fact, Medicare could use these data to change the way they pay by giving fee increases to only those providers that are delivering value to their beneficiaries. Taking that step is not the long-term solution but would definitely create incentives to increase the value of health care.

It’s possible to restrain swelling health care costs, and we don’t have to sacrifice quality to do it. Coordinating care and reforming the way we reimburse providers can help us move along the path toward this goal.

JEFF KORSMO

Executive Director

Mayo Clinic Health Policy Center

Rochester, Minnesota

Middle East economics

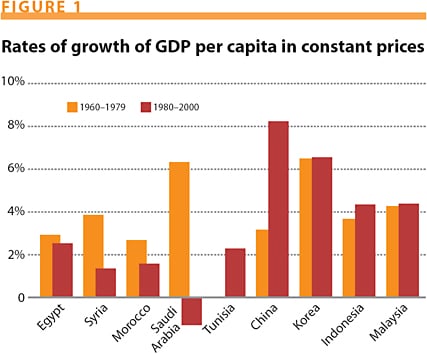

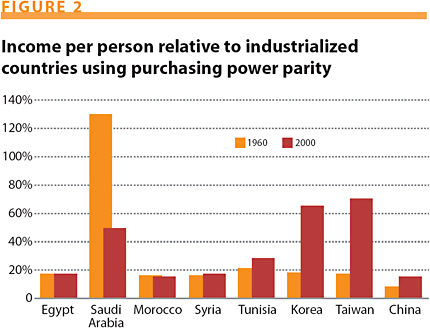

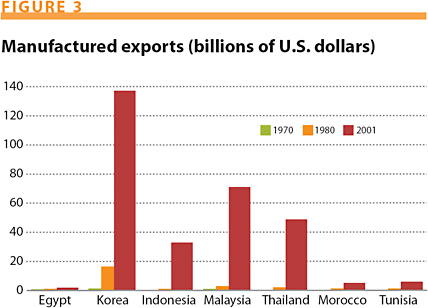

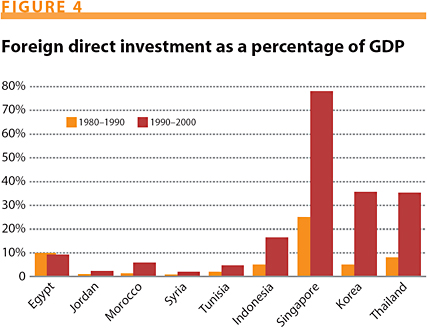

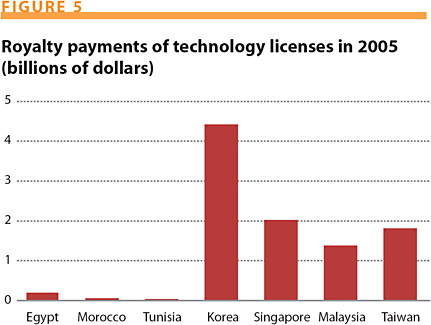

Howard Pack’s analysis of East Asia’s economic successes rings true (“Asian Successes vs. Middle Eastern Failures: The Role of Technology Transfer in Economic Development,” Issues, Spring 2008). The importance placed on education; stable macroeconomic policies and strong institutions; high rates of private investment; an openness to trade, investment, and new ideas; and a commitment to compete in the global economy are all factors in this economic success.

Unfortunately, in recent decades, growth in the Middle East and North Africa has not been as uniformly strong, although some countries in the region have done very well. I am encouraged, however, by recent signs of success. Over the past five years, economic growth across the Middle East and North Africa has averaged over 6% per year—the longest sustained growth performance since the 1970s. This has been accompanied by the creation of new jobs for the people of the region and improvements in social indicators.

Oil price rises have been part of the story, but only part. Recent gains are being driven by governments stepping back to make room for a dynamic private sector to introduce new technology and ideas to generate growth, jobs, and opportunities.

Egypt is one country that has embarked on wide-ranging reforms to open its economy, attract investment, and encourage innovation. The World Bank’s Doing Business report suggests that Egypt was the fastest reformer in the world in 2007. Progress can also be seen in other parts of the region: in Saudi Arabia, the Gulf states, Morocco, Tunisia, and Jordan, to name only a few.

Of course, there is a long way to go. The Middle East and North Africa face major challenges to provide jobs for the 80 million young people that will be entering the workforce over the next 15 years. Long-term solutions to address the impact of current food price increases on the poorest people will require improvements in agricultural productivity and efforts to ensure that growth both continues and is broadly based.

Responding to these opportunities and challenges, World Bank President Robert Zoellick has heard leaders of the region and committed to making the development of the Arab world one of the bank’s six strategic priorities.

The bank looks forward to working with partners in the region—governments, the private sector, and civil society—to scale up support to help them meet their own development goals. During extensive consultations, there has been a consensus on key priorities: supporting further reform and greater economic integration between the Arab world and the global economy to generate opportunities and jobs; improving the quality of education to encourage innovation and give young people vital skills; drawing more fully on the talents of the entire population, including women; strengthening the management of scarce water resources and overcoming environmental challenges; and providing opportunities for countries that remain in conflict.

I hope that Pack may have the opportunity to extend his valuable analysis of the lessons that can be drawn from the development experience of East Asia and the Middle East and North Africa to other regions, including Latin America.

I applaud the gains made by the East Asian region over the past few decades. At the same time, we should not forget that the countries of the Arab world have a proud history as the place where writing, advanced mathematics, navigation, and the early instruments of global trade were first introduced. They have led the world in the past, and I am hopeful that they can grasp current opportunities by capitalizing on existing and evolving knowledge to position themselves as leaders in fields such as renewable energy, water management, and financial services.

JUAN JOSÉ DABOUB

Managing Director

World Bank

Washington, DC

Homeland security research

“The R&D Future of Intelligence” by Bruce Berkowitz (Issues, Spring 2008) accurately portrays many of the significant technology-related challenges— and opportunities—confronting the intelligence community today and suggests four pragmatic “strategy principles” that could lead to a stronger R&D posture. I would, however, offer a few additional observations.

The major challenges cited by Berkowitz are “two developments—changes in the threat and changes in the world of R&D.” Although this is certainly true, I believe it is the feedback loop that exists between these two developments that is of even greater concern. Taken in combination, ongoing changes in both areas amplify the effects and demand from the intelligence community a degree of agility that is not delivered today. The potential for technology surprise is growing, while the community’s ability to rapidly exploit state-of-the-art technologies is declining.

The remedies proposed by Berkowitz have considerable merit; again, however, I would go a bit further. He first recommends more engagement between the intelligence community and the broader R&D community, suggesting that this would, over time, build a larger pool of cleared scientific personnel. Although necessary, I do not believe this is sufficient. I would augment his recommendation to include the identification of technologies that are today being driven by academic researchers and/or commercial interests and the development of aggressive strategies to engage with those R&D communities in unclassified settings. When separated from mission specifics, many of the technological capabilities needed by the intelligence community are well aligned with the needs of other organizations. This is particularly (but not uniquely) true in areas relating to information analysis, collaboration, and dissemination.

I fully agree with the need to ensure that intelligence community researchers are informed by real-world problems without being captive to those problems. The notion of prudent risk-taking to foster high-payoff innovations is an important one. I am hopeful that the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity will, over time, mature to fill the void that exists in this area today.

I also endorse the point Berkowitz makes several times about the need to align incentives with desired outcomes— from a community perspective. Although some problems are common to virtually all agencies within the intelligence community and would benefit from enterprise-wide solutions, other problems exist at the boundaries between organizations and will require collaboration simply to frame the problem so that a solution can be developed. Unfortunately, the intelligence community today is weak in both dimensions, and these are not issues that will be resolved by simply investing more in R&D.

Finally, I would observe that although Berkowitz’s article is specific to the intelligence community, the challenges and opportunities he identifies are not. Issues spawned by the globalization of science and technology are ubiquitous and, unfortunately, most governmental institutions are not well positioned to either exploit the opportunities or counter the challenges.

RUTH DAVID

President and CEO

Analytical Services

Arlington, Virginia

[email protected]

Nuclear safeguards

In “Strengthening Nuclear Safeguards” (Issues, Spring 2008), among the five factors considered by Charles D. Ferguson to explain why the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is confronting a crisis in its ability to detect undeclared nuclear activities, I believe the most relevant one is the “limited authority for the IAEA to investigate possible clandestine nuclear programs.” There is no doubt, as he rightfully stresses, that safeguards agreements have loopholes that can be exploited to develop nuclear weapons programs. It is therefore important to identify these loopholes and suggest practical measures to plug the gaps.

One of the main problems is that, contrary to what many experts believe, even when a state has ratified an Additional Protocol to its comprehensive safeguard agreement with the IAEA, agency inspectors still don’t have “access at all times to all places and data and to any person” as requested under the IAEA Statute.

This was made clear in the agency’s November 2004 report on Iran, which stated that “absent some nexus to nuclear material, the Agency’s legal authority to pursue the verification of possible nuclear weapons related activities is limited.”

It would also be a mistake to believe that the IAEA’s board of governors can “give the safeguards department the authority to investigate any persons and locations with relevance to nuclear programs,” as Ferguson suggests. Indeed, the board’s resolutions are not legally binding; only resolutions adopted by the United Nations Security Council under chapter VII of the UN Charter are mandatory.

Although it is correct to say that the Board “has usually been reluctant to exercise its existing authority to order a special inspection,” special inspections are not a panacea. In the case of the alleged construction in Syria of a clandestine nuclear reactor with help from North Korea, for instance, it is likely that if a special inspection had been requested by the IAEA, Syria would have had time to remove incriminating evidence before IAEA inspectors could access the site.

Under a comprehensive safeguards agreement, “in circumstances which may lead to special inspections … the State and the Agency shall consult forthwith.” As a result of such consultations, for which there is no time limit and which would normally take weeks or months, the agency “may obtain access in agreement with the State.” If the state refuses, the board of governors can decide that an action is essential and urgent, but that procedure can also take weeks.

A special inspection will therefore be useful mainly in cases where nuclear material or traces thereof cannot be removed, as would have been the case in 1993, with the request to access a waste storage facility in North Korea. If Syria wished to dispel any suspicion that nuclear-related activities were taking place at the al Kibar site bombed by Israel in September 2007, it could have invited the IAEA to immediately conduct a special inspection there, as Romania did in the early 1990s to verify previously undeclared activities. Had Syria an Additional Protocol in force, agency inspectors would have long since requested “complementary access” to the incriminated site.

As underlined by Ferguson, a strengthened safeguards system is crucial for securing international security. The international community knows what could and should be done to improve the nonproliferation regime. What is missing is the political will to act.

PIERRE GOLDSCHMIDT

Nonresident Senior Associate

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Washington, DC

[email protected]

Charles D. Ferguson has covered a complex subject succinctly yet thoroughly. He ably draws out the main contemporary safeguards themes, especially how to improve the capability to detect clandestine nuclear programs, manage an expanding safeguards workload, and ensure that there is political will to deal with violations. In this brief response, I will highlight some key issues for the safeguards system.

Although seen by many as a deterministic system, actually safeguards are about risk management: how to identify and address proliferation risk, using available authority and resources. The principal proliferation risk has always been from unsafeguarded nuclear programs involving states outside the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or non–nuclear-weapon states (NNWS) with undeclared nuclear activities (thereby being in violation of the NPT). In the non-NPT states (India, Israel, and Pakistan, and depending on one’s legal view, North Korea), most facilities are outside safeguards. Bringing the nuclear programs of the nuclear-weapon states and the non-NPT states under appropriate verification is the goal of the proposed fissile material cutoff treaty.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the principal proliferation indicator for NPT NNWS was thought to be the diversion of nuclear material from safeguarded facilities. Hence, safeguards developed as a facility-based system with an emphasis on material accountancy. Discovery of Iraq’s clandestine nuclear activities prompted a major program by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) with member-state experts to redesign the safeguards system, especially to better address the issue of undeclared activities. As a consequence, safeguards are changing to an information-driven, state-level system. The essential foundation for strengthened safeguards is the Additional Protocol (AP), giving the IAEA more extensive rights of access and information. States must do more toward achieving universalization of the AP—it is high time that all nuclear suppliers made the AP a condition for supply.

ALMOST ALL U.S. BIRDWATCHERS WHO HAVE BEEN ACTIVELY INVOLVED IN THEIR HOBBY FOR MORE THAN A DECADE PROBABLY HAVE THE SENSE THAT THERE ARE NOW FEWER MIGRATORY BIRDS THAN THERE WERE WHEN THEY FIRST BEGAN BIRDING.

Current proliferation challenges have come from clandestine activities, not mainstream nuclear programs. More needs to be done to develop detection capabilities for undeclared programs and to redirect safeguards efforts toward this problem. Detection of undeclared nuclear activities is a major challenge; the IAEA cannot be expected to do this unaided, as the agency can never match the intelligence capabilities of a major state. States need to be more willing to share information with the agency, particularly on dual-use exports and export denials and intelligence information. For its part, the IAEA must be more active in using its existing authority, including special inspections and rights under its Statute.

One area that might be given further attention concerns the IAEA’s processes, especially on compliance. Particularly with the Iranian case, politics have intruded into the deliberations of the IAEA’s board of governors. This may be difficult to avoid, since the board comprises representatives of governments, but the board’s work was made more complicated through the agency’s involvement in negotiations with Iran. The IAEA’s Statute is clear: Questions relating to international peace and security are to be referred to the United Nations Security Council. Enabling the agency to deal more effectively with proliferation cases depends on both improving its technical capabilities and refocusing on its technical responsibilities.

JOHN CARLSON

Director General

Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office

Barton, Australia

John Carlson is a former chair of the IAEA’s Standing Advisory Group on Safeguards Implementation.

Protecting migration routes

Almost all birdwatchers in the United States who have been actively involved in their hobby for more than a decade probably have the sense that there are now fewer migratory birds than there were when they first began birding.

In fact, one birder, Barth Schorre, who photographed birds for 30 years on the Texas coast, recently recounted his concerns by saying that “Over the years I became aware that I was not only seeing fewer species, but also fewer total numbers of birds,” referring to the years from 1977 to 2004, when he observed and photographed spring migrants at a single 3.5-acre site in south Texas. “Looking back through my log books I can see that on a typical spring day in the 1980s, a list of migrant species filled a page to overflowing. More recently I am logging the observations of three or four days on a single page.”

Concerns about spring bird migration and many of the world’s great animal migrations, including scientific data that support the observations of amateur naturalists, are highlighted by David S. Wilcove in “Animal Migration: An Endangered Phenomenon?” (Issues, Spring 2008). Working as I do for the American Bird Conservancy, an organization dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas, I am naturally engaged in an effort to address the issue that Wilcove so eloquently addresses, the same one that is being witnessed firsthand by birdwatchers across the country.

Fortunately, the issue has also raised concerns among some politicians. Reps. Ron Kind (D-WI) and Wayne Gilchrest (R-MD) have recently introduced legislation to fund efforts to help protect migratory birds. The act, H.R. 5756, reauthorizes an existing law, the Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA), but at significantly higher levels, to meet the growing needs of our migrant songbirds, many of which are in rapid decline.

NMBCA supports partnership programs to conserve birds in the United States, Canada, Latin America, and the Caribbean, where approximately five billion birds of over 500 species, including some of the most endangered birds in North America, spend their winters. Projects include habitat restoration, research and monitoring, law enforcement, and outreach and education. To date, more than $21 million from NMBCA grants has leveraged over $95 million in partner contributions. Projects involving land conservation have affected about 3 million acres of bird habitat.

Under the new bill, the amount available for grants would increase to $20 million by 2015. We believe that this support can make an important difference in reversing the negative trends of many migratory songbirds.

MICHAEL J. PARR

Vice President

American Bird Conservancy

Washington, DC

[email protected]

David S. Wilcove calls attention to a major conservation issue. His frequent mention of migratory fish particularly hit home for me, a biologist who works with native fish in California.

California has the southernmost populations of 13 species of anadromous fishes (6 salmon, 2 sturgeon, 2 lampreys, and 3 smelt). In addition, the salmon, steelhead, and sturgeon have been divided into 22 distinct taxonomic units, most of them endemic to the state. All of these migratory fishes are in decline, and 11 have been listed as threatened or endangered.

The persistence of these fish is astonishing. Southern steelhead still migrate to the ocean from streams as far south as Malibu and San Diego. Four runs of Chinook salmon persist in the great Central Valley, although numbers are down considerably from the 1 to 2 million fish that once returned every year. The Klamath River still supports 10 species of oceangoing fish and multiple runs of salmon and steelhead.

As Wilcove points out, the fish have value far beyond their harvest value. They are spectacular and iconic representatives of our wild heritage. They are also still part of our ecosystems. Even hatchery-driven runs of salmon coming up channelized rivers can support diverse wildlife, and nutrients from their flesh find their way into the grapes of riparian vineyards.

The abundance of migratory fishes results from a diverse topography, a long coastline, and one of the most productive coastal regions in the world. All of this means that whether in fresh or salt water, the fish live mostly in California. Thus, their rapid decline in recent years is entirely our fault; we have done everything bad imaginable to their watersheds.

Unfortunately, most Californians are unaware of these amazing runs of migratory fish and their status. Awareness comes only when water becomes less available because it is needed to sustain endangered fish. Thus, a federal court has ruled twice (for different species) in the past year that the giant pumps in the Sacramento–San Joaquin delta must pump less water, sending it south for agricultural and urban use. The plight of fishermen also made the news when fisheries were shut down because of the rapid decline of salmon populations.

What can be done? One view is that it is already too late for most migratory fish in the state; therefore the most we can do is maintain a few boutique runs to view in a Disneyland-like atmosphere. I prefer a more optimistic view, relying on the resilience of the fish to respond to major improvements in their habitats. Thus, I am involved in a fast-track effort to bring back Chinook salmon to 150 miles of the now-dry San Joaquin River, an incredibly complex task. Perhaps the biggest return from this endeavor will be for people of the San Joaquin Valley to see salmon in a living stream, a phenomenon that has been absent for over 75 years. I hope that Wilcove’s writings will inspire further efforts along these lines.

PETER B. MOYLE

Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology

Center for Watershed Sciences

University of California

Davis, California

[email protected]

David S. Wilcove provides a rich account of animal migration and an incisive analysis of the attendant conservation challenges. To his credit, he assiduously avoids the doom-and-gloom approach that pervades much environmental literature and alienates most of the public. So, despite my concern that bad news is rarely motivating, I worry that conserving migrations may be more difficult than the author suggests.

The first challenge that Wilcove identifies is the coordination of planning across borders in light of the large distances involved in many animal migrations. And the scale of movement points to a deeper problem. Although Wilcove proposes that, “animal migrations are among the world’s most visible and inspiring phenomena,” it seems that many, even most, are invisible to the public, in substantial part because we are not used to perceiving the world at such a scale. People generally know that songbirds “head south” for the winter, but few understand the enormity of the space these creatures traverse. I’d wager that not 1 in 10 Wyomingites knows that their state hosts the third longest overland mammal migration in the world—the movement of pronghorn from the Red Desert to Grand Teton National Park. And returning to Wilcove’s geopolitical worry, when one realizes the challenge of making this pathway, which is entirely within Wyoming, the country’s first National Migration Corridor, the difficulties of protecting pathways that cross national borders become daunting.

The second problem that Wilcove raises is that of protecting animals while they are still abundant. Of course, we know that plentitude is no guarantee against extinction, as evidenced by the Rocky Mountain locust, whose swarms were arguably the greatest movement of animal biomass in Earth’s history. But the deeper problem is that we’re not talking about saving species understood as material collections of organisms. Rather, as Wilcove indicates in the subtitle of his essay, we are proposing to safeguard processes. Ecologists are coming to understand that organisms, populations, species, communities, and ecosystems may best be understood in terms of what they do: A thing is what it does. So an ecosystem is nutrient cycling, soil building, and water purification. Likewise, migrating gray whales, cerulean warblers, and pronghorn are not objects but waves of life, in the same sense that a wave is not the moving water but the energy coursing through a fluid. We can no more conserve a migratory species by keeping a cetacean in a tank, a bird in a cage, or an antelope in a zoo than by storing DNA in a test tube.

My concerns regarding political coordination and philosophical conceptualization are not meant to dissuade anyone who wishes to conserve the endangered phenomena of animal migration. We desperately need clear, intelligent, impassioned, and hopeful voices such as that of Wilcove. But we must fully grasp the nature of the challenges that lie ahead, for humans and our fellow animals.

JEFFREY A. LOCKWOOD

Professor of Natural Sciences and Humanities

University of Wyoming

Laramie, Wyoming

[email protected]

Reforming medical liability

Frank Sloan and Lindsey Chepke are to be commended for calling attention to fundamental problems in America’s medical liability system (“From Medical Malpractice to Quality Assurance,” Issues, Spring 2008). The existing system compensates few patients who have been injured, its deterrent effect is limited, its administrative costs are very high, and it does little to improve patient safety. And, as they point out, the types of medical liability reforms that traditionally have generated political traction, including caps on noneconomic damages, do little to address these shortcomings.

Of course, these problems are not new, and a variety of both incremental and far-reaching reform proposals to address them have been advanced through the years by political leaders, academics, policy advocates, and interest groups. Among these, the nonprofit organization Common Good (of which this author is general counsel) has been active in promoting the concept of developing administrative health courts, with specialized judges, independent expert witnesses, and predictable damage awards. In many ways, the health court proposal bears a resemblance to workers’ compensation, as a structured approach to compensating a particular type of injury, with strong linkages to risk-management efforts intended to reduce errors. With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Common Good has worked with a research team from the Harvard School of Public Health to develop a conceptual proposal for how this system might work and to identify opportunities to test this proposal in pilot projects.

As far as implementation is concerned, transformative reform proposals tend to face considerable political challenges. Still, there are a number of ways in which some variant of the health court/administrative compensation proposal might be adopted at the state level. It’s not inconceivable that a state legislature might establish a demonstration program for compensating certain types of injuries outside the tort system. It’s more likely, however, that a hybrid model might be created that linked some sort of error-disclosure program with structured arbitration. It might also include supplemental insurance (purchased by the patient to protect against the risk of injury) and/or scheduled damages. To align incentives between health care professionals and institutions, these initiatives might well be paired with enterprise liability or insurance.

Although these reforms may take different and daedal shapes, they are necessitated by the complex problems of America’s medical liability system. If these enduring problems were easy to fix, policymakers would have done so decades ago. Still, though solutions may be challenging, they’re far from impossible. Sloan and Chepke’s article and the book from which it is drawn will undoubtedly play a significant role in continuing to spur interest in promising reform alternatives.

PAUL BARRINGER

General Counsel

Common Good

Washington, DC

[email protected]

A key assumption of the book is that what is really wrong with science advising is that scientists lack a clear view of their choices and of what they are doing. Pielke seems to believe that once scientists get this straight, the rest of what needs to happen in the advising process will fall into place. I wish it were that simple.

A key assumption of the book is that what is really wrong with science advising is that scientists lack a clear view of their choices and of what they are doing. Pielke seems to believe that once scientists get this straight, the rest of what needs to happen in the advising process will fall into place. I wish it were that simple.

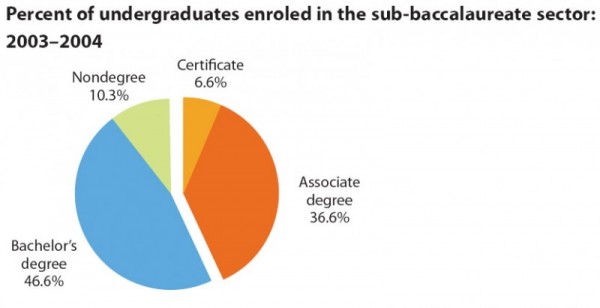

Douglass is concerned with leading U.S. public research universities. Expenditures per student are higher at public research universities than at public comprehensive institutions, where they are in turn higher than at public two-year colleges. A considerable body of research by economists suggests that a student’s economic gains from attending a higher education institution depend on the level of expenditures per student at the institution. However, in most states, the share of students who come from lower- and lower-middle-income families (as measured by the number of Pell Grant recipients) is higher at the public two-year colleges than at the public comprehensives, and is higher there than at the flagship public research universities. Hence the students for whom public higher education is supposed to serve as a vehicle for social mobility are, for the most part, attending the more poorly funded public higher education institutions. A notable exception occurs in California, where a number of the campuses of what is arguably the nation’s finest public research university system, the University of California (UC), rank near the top of flagship publics in terms of the shares of their students who are Pell Grant recipients.

Douglass is concerned with leading U.S. public research universities. Expenditures per student are higher at public research universities than at public comprehensive institutions, where they are in turn higher than at public two-year colleges. A considerable body of research by economists suggests that a student’s economic gains from attending a higher education institution depend on the level of expenditures per student at the institution. However, in most states, the share of students who come from lower- and lower-middle-income families (as measured by the number of Pell Grant recipients) is higher at the public two-year colleges than at the public comprehensives, and is higher there than at the flagship public research universities. Hence the students for whom public higher education is supposed to serve as a vehicle for social mobility are, for the most part, attending the more poorly funded public higher education institutions. A notable exception occurs in California, where a number of the campuses of what is arguably the nation’s finest public research university system, the University of California (UC), rank near the top of flagship publics in terms of the shares of their students who are Pell Grant recipients. Mike Moore is the former editor of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a periodical with a strong arms control perspective, and thus it is not surprising that Twilight War is an extended tract arguing against the desirability of U.S. space dominance. This concept is defined as an overwhelming advantage in space capability that would allow the United States to control who has access to outer space and what is done there, and, if it so chooses, to use space as an arena for the projection of U.S. military power. Moore suggests that a coherent group of “space warriors” in the Department of Defense, the Air Force, various think tanks, Congress, the aerospace industry, and, at least during its first term, the Bush administration, believes that the capability to dominate space should be a top-priority U.S. goal. Moore writes that this view “is uniquely in tune with twenty-first century American triumphalism,” defined as the belief that “America’s values, perhaps divinely inspired, ought to be the world’s values.” Indeed, throughout the book he suggests that such exceptionalism, not geostrategic security considerations, is the underlying motivation behind the U.S. rhetoric regarding space dominance, thus giving the United States the right to define for the rest of the world, not just itself, what is acceptable behavior beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

Mike Moore is the former editor of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a periodical with a strong arms control perspective, and thus it is not surprising that Twilight War is an extended tract arguing against the desirability of U.S. space dominance. This concept is defined as an overwhelming advantage in space capability that would allow the United States to control who has access to outer space and what is done there, and, if it so chooses, to use space as an arena for the projection of U.S. military power. Moore suggests that a coherent group of “space warriors” in the Department of Defense, the Air Force, various think tanks, Congress, the aerospace industry, and, at least during its first term, the Bush administration, believes that the capability to dominate space should be a top-priority U.S. goal. Moore writes that this view “is uniquely in tune with twenty-first century American triumphalism,” defined as the belief that “America’s values, perhaps divinely inspired, ought to be the world’s values.” Indeed, throughout the book he suggests that such exceptionalism, not geostrategic security considerations, is the underlying motivation behind the U.S. rhetoric regarding space dominance, thus giving the United States the right to define for the rest of the world, not just itself, what is acceptable behavior beyond Earth’s atmosphere. The Politics of Space Security is actually two books in one. The first and last sections of the book contain a thoughtful analysis of various perspectives for understanding the concept of space security and their application to understanding the current situation and future prospects. Moltz’s first two chapters look at how other analysts have understood space security and set forth an alternative explanation that stresses a growing awareness of the environmental consequences of actions such as the testing of nuclear weapons in outer space in the early 1960s, which created electromagnetic effects that interfered with satellite operations in both the short and potentially the longer term, and the kinetic destruction caused by antisatellite weapons, which could create long-lived debris in heavily used orbits. Moltz writes as his “main conceptual argument” that “environmental factors have played an influential role in space security over time and provide a useful context for considering its future [emphasis in original].”

The Politics of Space Security is actually two books in one. The first and last sections of the book contain a thoughtful analysis of various perspectives for understanding the concept of space security and their application to understanding the current situation and future prospects. Moltz’s first two chapters look at how other analysts have understood space security and set forth an alternative explanation that stresses a growing awareness of the environmental consequences of actions such as the testing of nuclear weapons in outer space in the early 1960s, which created electromagnetic effects that interfered with satellite operations in both the short and potentially the longer term, and the kinetic destruction caused by antisatellite weapons, which could create long-lived debris in heavily used orbits. Moltz writes as his “main conceptual argument” that “environmental factors have played an influential role in space security over time and provide a useful context for considering its future [emphasis in original].”