Child Support in the Age of Complex Families

Government efforts to engage noncustodial fathers in supporting their children should take advantage of the reality that these dads care more about their offspring than is commonly assumed.

The American family doesn’t look like it used to—at least for the economically disadvantaged. Parents are often unmarried when their children are born. Unmarried couples’ unions are often unstable; they frequently split soon after the birth of a child and the partners often quickly form new relationships. From a child’s perspective, this means a daddy-go-round of successive father figures with varying levels of engagement and support. Along the way, both parents often have children with other partners, leading to complex families. As 42% of US children are now born outside of a marital bond, some observers have labeled the United States a “complex family society.”

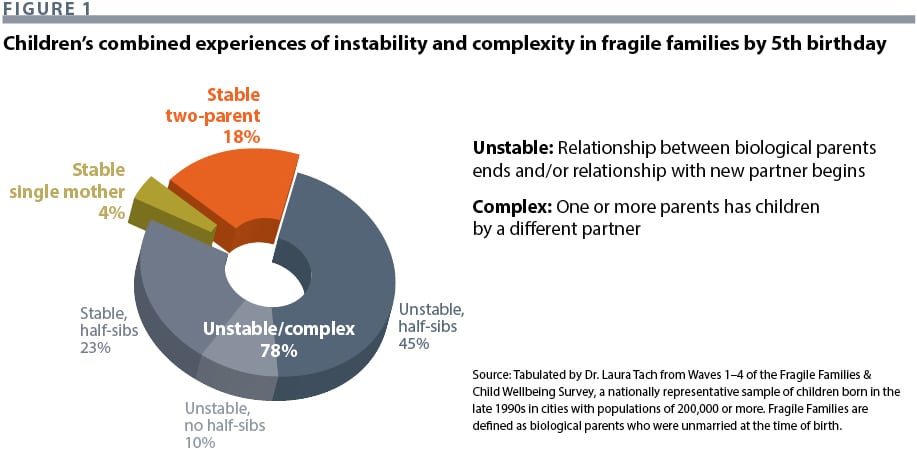

To acquire a clearer picture of these families, Laura Tach, Sara McLanahan, and I turned to the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study, a longitudinal birth cohort survey that began in 2000 and is nationally representative of births in large cities. We limited our analysis to children born to unmarried parents, since most children of disadvantaged parents are now born outside of a marital bond. The results were stunning. By age five, nearly 80% of the children had experienced either instability or complexity in some form, and almost half had experienced both. (See Figure 1.)

These levels of instability and complexity are unprecedented in US history. Moreover, the United States is unique among rich nations in this regard. And the trends are concentrated among the disadvantaged. In fact, whereas nonmarital childbearing has risen dramatically among non-college-educated women, it continues to be relatively rare among those with college degrees, for whom divorce rates have been falling since the 1970s. In sum, whereas the family lives of those at the bottom of the educational distribution grow ever more unstable, the opposite trend characterizes those with a college degree. Although instability and complexity may be, in part, a consequence of inequality, complex families are also a cause of the diverging destinies of US children by socioeconomic status.

During the 2000s, the Bush administration labeled these trends a crisis and launched a campaign to promote marriage. It funded public information campaigns and launched randomized controlled trials of a variety of interventions aimed at improving the relationship skills of unmarried couples who were expecting a baby or had just given birth. The most successful of these programs did have some impact on instability. Oklahoma’s Family Expectations, for example, saw an encouraging increase in one measure of family stability three years after random assignment. Other interventions, however, registered no effect, perhaps because it proved so hard to interest couples in participating in the programs, so the “treatment” ended up being weak. Qualitative interviewers who followed couples in such programs over time noted that participants reported that they were valuable, so we shouldn’t dismiss them. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that such efforts alone will turn these trends around.

Given the reality that many children are now born into unstable and complex families, the challenge is to ensure that they nonetheless can thrive. The nation’s child support system solves a key practical problem in a complex family society such as ours: how to get resources from parents (usually fathers) to children who do not live with them. The system requires fathers to contribute financially when the parents’ relationship ends. Yet—at least implicitly—the current system is built on the widely shared assumption that these absent fathers feel no responsibility for their offspring and must therefore be forced to provide. But this assumption could be wrong, and if it is, then this heavy-handed approach to enforcing paternal responsibility could be blinding us to other approaches to engaging fathers in financially and emotionally supporting their children.

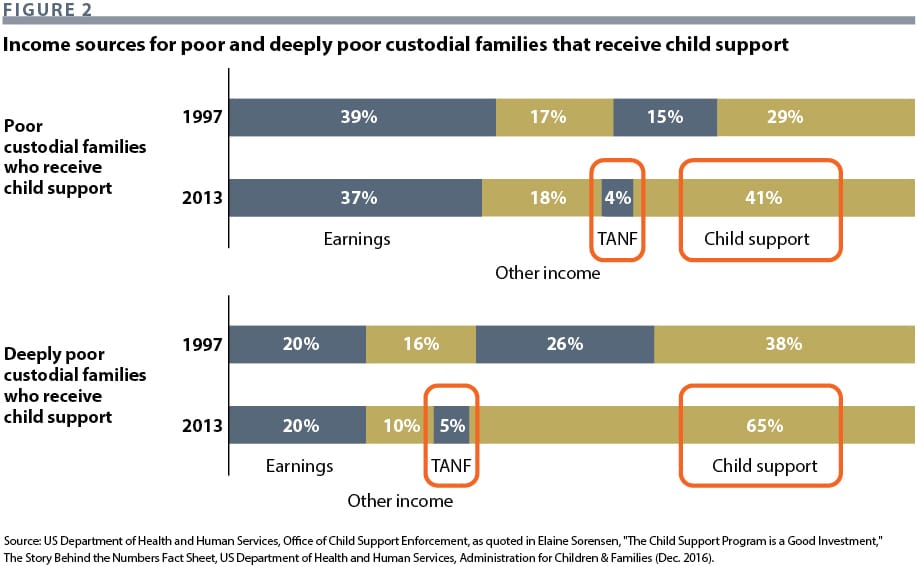

Let’s begin with what’s good about the current child support system. Though far from perfect, it has enormous reach. Its caseload covered one in five US children in 2016, and fully half of all poor children are served by the program. In 2013, child support payments for poor custodial parents who received them made up, on average, 49% of their annual personal income. For those custodial parents below poverty who were paid the full amount owed, child support accounted for over two-thirds (70.3%) of average annual personal income. (See Figure 2.)

The child support system has grown in importance during the past two decades as the federal government’s Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program has withered as a result of welfare reform. By contrast, during this period the child support system has become more adept at collecting payments from noncustodial parents with an order. As a consequence, noncustodial parents who pay are contributing a much larger share to custodial parents’ total income. The result is that when poor custodial parents receive child support, both parents contribute more or less equally, and it’s the parents, not the taxpayers, who provide the lion’s share of support.

It behooves us, therefore, to explore how an evolving understanding of noncustodial fathers can be used to improve the child support system, which is such a vital source of support for an increasing number of US children who live apart from one of their parents.

New view of fathers

The key to making the child support system even more effective is to capitalize on fathers’ desires—evident in both survey and qualitative data—to be involved in their children’s lives. This evidence goes against the conventional wisdom that unmarried fathers selfishly flee the moment they hear of an impending pregnancy, act like boys instead of men, and leave the mother holding the proverbial diaper bag.

Let’s start at the time of a child’s birth. Data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing survey show that the conventional wisdom is far from the truth. According to mothers’ reports (which are more conservative than fathers’), four out of five fathers contributed financially during her pregnancy, three-fourths had visited her in the hospital by the time she was interviewed by the survey team, and eight in ten said the father planned to continue to contribute financially. An astonishing 99.8% of fathers interviewed said they wanted to be involved in their children’s lives. And 93% of mothers agreed.

Over the past two decades, Timothy Nelson, Laura Lein, and I (along with several dozen graduate students) have conducted repeated in-depth interviews with 428 low-income noncustodial fathers of 753 children in four metro areas: Austin, Texas; Camden, New Jersey/Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Charleston, South Carolina; and San Antonio, Texas. In 2013, Nelson and I published Doing the Best I Can, a book on the social meaning of fatherhood based on the Camden/Philadelphia interviews. Our book, along with the findings of several other in-depth interview studies, reveals that these men often identified fatherhood as a key source of meaning and identity in their lives.

We asked each father a question that proved particularly revealing: What would your life be like if you hadn’t had your children? Mike told us, “I’d probably be dead somewhere, or back in jail, in and out of rehabs…. It’s given me something to fight for, something like a destination. I got to be somewhere.” Apple said, “I guess after I got caught up in the bad life, as far as drugs and all, the kids helped me keep my head up, look forward…. Kids give you something to live for.” According to Alex: “I would be out getting high because I would not have [anything]. I would have my girlfriend, but my baby is the most important thing in my life right now.”

We asked Elvis, What did you think your future was going to be before you had him? “I wasn’t going to live past the age of 30,” he said. And then once you had him? we asked. “He came into the picture when I was like 27, and that all changed,” he answered. “Everything changed. My whole life changed.”

In our 2005 book, Promises I Can Keep, Maria Kefalas and I described 165 in-depth interviews with single mothers in Camden and Philadelphia, and we advanced the argument that a key reason so many poor women put motherhood before marriage was that while they aspired to marriage, they doubted a poor but happy marriage could survive. Yet they viewed motherhood as a key source of meaning and identity; children filled the void when other sources—such as a chance at a meaningful career—were limited. In Doing the Best I Can, Nelson and I reported on evidence that the same could be said for young men. So much for the “love ’em and leave ’em” narrative.

Another reason I advocate for greater attention to child support is the mounting body of evidence that it enhances child well-being. A meta-analysis by Paul Amato and Joan Gilbreth included 14 studies that measured the impact of child support on child well-being. Two subsequent studies have been conducted by Laura Argys and colleagues and Lenna Nepomnyaschy and coauthors. Taken together, this body of empirical research shows that child support, broadly conceived, has a positive impact on child well-being, including cognitive skills, emotional development, and educational attainment. We’ve already seen what a significant effect child support can have on a custodial mother’s income, but these analyses tie the receipt of child support directly to measures of child well-being. And some researchers find evidence that the positive impact of child support, broadly conceived, exceeds that of other sources of family income, hinting at a special salience for children.

Flaws in the system

In spite of all the value I find in the current child support system, I maintain that in some fundamental ways the system is broken. And there is evidence—both “hard” evidence from quantitative studies as well as more speculative qualitative data—to suggest that at least for some, the system may actually compromise child well-being.

To start with, a more fine-grained look at the very empirical studies I just referenced shows that there may be cause for concern. Those studies that separate out the various forms of support show that most, if not all, of the positive effect of child support on child well-being accrues to children whose parents have informal arrangements; that is, agreements that are developed by the parents rather than imposed by the court. More worrying, one carefully done study shows that formal child support receipt is associated with elevated child behavior problems.

Other hints that something may be wrong can be found in patterns of participation over time. Though the system has become more effective over the years in collecting on behalf of those with formal orders, it has become less effective at convincing custodial parents to participate at all. This is certainly not because the number of custodial parents is falling. Some of the fall-off in participation is no doubt due to the decline in the welfare rolls (welfare recipients are required to participate). But child support is a near-free service for anyone who wishes to apply. The declines appear to be due to the fact that custodial parents are less and less likely to see the need to engage with the system, prefer informal arrangements, or worry that their child’s father might not have the capacity to keep up with a formal award. Given the highly punitive nature of the current system, the costs to such men could be steep. Are custodial parents voting with their feet? Perhaps so.

Robert Doar, the Morgridge Fellow in Poverty Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, has offered one solution to this problem: require single mothers on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to sign up, just as welfare recipients are required to do. Doar recommends allowing for good cause exemptions and stipulating that the support would be disregarded in calculating SNAP benefits. But for programs that people value and are not invested in avoiding, behavioral science suggests that creating patterns of easy enrollment (defaults, nudges, and so on) can lead to greater participation—and satisfaction—than requirements or threats. Better results are often obtained by smoothing a process that could otherwise be demeaning or cumbersome. Plus, nudges don’t put the government in the position of denying needy children access to food.

But note my caveat in the prior paragraph: “for programs that people value and are not interested in avoiding.” We have to make sure that participants in the child support system find it valuable. And we have to make sure it actually promotes child well-being.

Rachel Butler, a PhD student at Johns Hopkins University, looked closely at the transcripts of the 429 interviews in our four-city study to identify comments related to formal, informal, and in-kind child support and to code them by theme. She took care to count only words or phrases that were “naturally occurring,” that is, introduced by the interviewee, not the interviewer. The results were striking.

The themes most closely associated with formal child support were legal terms, a loss of power and autonomy, and financial terms. Court is the most common word used. Jail is the next most common. We didn’t find frequent mentions of court surprising, since in most locales, orders for unmarried parents are often set by an administrative judge. Jail was surprising. Although every state has either civil or criminal statues on the books that permit incarceration for nonpayment, there have been no national estimates of how frequently the practice is used. We turned to Lenna Nepomnyaschy and her graduate student Sarah Gold, both experts on the child support modules in the Fragile Families survey, to see if they could construct such an estimate. Their analysis revealed that 12%-13%—roughly one out of eight—nonmarital children covered by a child support order had seen their father incarcerated for nonpayment of child support by the time they reached age nine.

No wonder that one father said his participation in the formal system “makes me feel like I need a judge to make me responsible!” Another said the system made him feel like “some kind of criminal.”

Next comes loss of power and autonomy, exemplified by phrases such as “they take it,” “jacking me up,” “they come looking for you,” “[makes me feel like I’m] not man enough,” “hounding me,” “she can whip me with that” [the threat of child support], “at their mercy,” and “crushing [my] manhood.”

Needless to say, these are not good testimonials for the program. The final theme is financial, with words and phrases such as “debt,” “impossible [financial demands],” “in the hole,” “they don’t credit me” [in reference to informal and in-kind contributions, which are not counted toward child support obligations in any jurisdiction], and “just another bill to pay.”

Sociologists who conduct analyses such as these often examine what isn’t present in narratives as well as what is. Notably absent are mentions of positive co-parent relationships, any mention of the father/child bond, or any sense that formal child support counts in fathers’ minds as a form of provision.

Language used to describe informal child support is strikingly different from that used in reference to formal support. Positive statements about the co-parenting relationship are particularly common. The word “agreement” is used most frequently. The other prevalent theme is positive expressions of power and authority—for example, the use of “give” rather than “take”.

Phrases indicating positive co-parenting include “she trusted me,” “we made an arrangement,” “we go together,” “do things together,” “sit down and discuss things,” “a bargain we struck,” “she can count on me,” “we split everything in half,” “worked it out directly,” and “worked it out like civilized people.” Positive expressions of power and autonomy include phrases such as “I take care of things,” “I give his mom some money,” “I send some money to my [little] girl,” “I put no limit on what I give,” “my first priority,” “I pay faithfully,” “I do more than others,” “I always make sure,” “it fills my responsibility,” and “I do for her.”

Before we move on, I must note that there is a potential dark side to feelings of power and autonomy when exercised inappropriately. Whereas we might find it encouraging when fathers feel empowered in general—and especially when they feel empowered to fulfill their roles as parents—most of us would find it worrying if fathers used informal contributions in coercive ways, lording it over their former partners. We do see examples of both in the data and note that one virtue of the formal system is that it allows the custodial parent to retain control.

Discussions of in-kind support also evoke distinctive language. In particular, they often include explicit references to the father/child bond. In another analysis of these data, Jennifer Kane, Timothy Nelson, and I find that disadvantaged fathers in particular prefer in-kind support because it serves “to repair, bolster, sustain, and ensure the future of their connections to their children.” We also find that “in-kind contributions can be repositories of paternal sentiment,” and that “a repository of memories—special times on which they hope their children can draw as a reminder that Dad really cares,” especially if they cannot be present in their children’s lives due to incarceration, maternal gatekeeping, or other reasons. In-kind contributions are often made in direct response to what children want or need. Phrases include “My daughter knows if she ask me, it’s there,” “I talk to her about what she needs,” “it’s more personal,” “I had to get it for her [when she told me how much she wanted it],” “I like to take them [shopping],” “I make sure my son got what he need,” and “I wanna show them the love [by buying them things].”

A second theme associated with in-kind support (also a prevalent, but not a predominant, theme in describing informal support) is provision. Representative phrases address meeting needs: “I put clothes on her back and shoes on her feet,” “I am in charge [of paying for Pampers and formula],” “whatever she wants,” “whatever he requires,” “anything I have,” “I take care of mine” or “I take care of my share,” “I try to provide anything he needs,” and “I want my kids to have the best.”

Child support relies, at least some degree, on the goodwill and cooperation of the fathers and mothers who are eligible to participate. The interviews we conducted leave no doubt that noncustodial fathers prefer informal arrangements for supporting their children. The analyses also hint at what might lie beneath the vexing finding that informal arrangements seem to contribute more to child well-being and that participation in the formal child support system could be producing unintentional corrosive effects. At least for the noncustodial parents we studied, formal child support is associated with an adversarial, dignity-stripping process that reduces any sense of provision to a debt, to “just another bill to pay.” Meanwhile, the formal system does little, if anything, to help parents build a positive co-parenting relationship or grant dignity to men who do pay. Furthermore, child support does nothing to build the father/child bond.

The question we need to confront is, what would it take to make child support a truly family-building institution? Focusing exclusively on securing economic resources for children—the worthy purpose of the formal child support system—is not enough to achieve that goal.

Before I turn to policy recommendations, allow me to propose some criteria for intervention. For the past several years, Laura Tach, Luke Shaefer, and I have been advocating for what we’ve called a dignity litmus test. We’ve encouraged policy-makers and practitioners to ask whether the intervention serves to offer participants a sense that they are valued members of the community or whether it generates stigma and shame. Along with economic resources, whatever policy solutions we adopt ought to lend dignity to participants. Other experts—including john powell of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, and Ai-Jen Po of the National Domestic Worker’s Alliance—have added another dimension to our thinking, emphasizing the importance of power and autonomy. Thus, a holistic effort to promote mobility from poverty should be guided by these three principles: economic resources, power and autonomy, and respect in the community. (I’d like to note here that these principles have been embraced and endorsed by the U.S. Partnership on Mobility from Poverty, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and administered by the Urban Institute. Po, powell, and I are members of the partnership.)

Principle into practice

Let’s take each of these criteria in turn. To advance the goal of ensuring that kids receive sufficient economic resources, while also ensuring that fathers have sufficient resources to give and are motivated to do so, we need to make it feasible for every noncustodial parent, no matter how limited their circumstances, to participate. Until fairly recently, it could be argued that the formal child support system was, for some, actually diminishing motivation and capacity to pay due to unsustainable awards, a lack of adequate self-support reserves, incarceration without consideration of whether a father had the ability to pay, and the treatment of incarceration as a form of “voluntary unemployment”—which meant arrears continued to mount when fathers were in prison. However, since December 2016, thanks to the rule issued by the Obama administration’s Office of Child Support Enforcement, these practices are now discouraged or disallowed

But we need to go further. We need to find a way to engage fathers with very low incomes or very unstable employment. Mechanisms for real-time modification are needed. And—as I will suggest later—alternative kinds of support should count.

Equally important is to deal head-on with the difficulties that men with children by multiple partners face—a condition that almost inevitably leads to unsustainable awards. Consider the case of Texas, which employs a percentage-of-income formula (one of three formulas states use) to set child support awards. If a noncustodial father has three children by one partner, he will be expected to pay 30% of his net income in child support. But if those children are with three partners, his obligation will be roughly 50%. If fathers with multiple partners fall into arrears, which they’re probably likely to do, a state can withhold up to 65% of their wages if certain conditions apply. No state that I know of has figured out a way to deal with this dilemma. But as Figure 1 illustrates, a large number of fathers and children are in this situation. The goal here is not to let fathers off the hook, but to encourage more fathers to pay—and more mothers to sign up for the program—by making it feasible for every father to participate.

Second, how do we meet the goal of supporting children without stripping fathers of power and autonomy, as the formal system now does? I argue that we should make formal support more like informal support, which stokes positive feelings of power and autonomy. Minnesota offers an example of how this can be done. When serving as presiding judge of the Hennepin County Family Court, Bruce Peterson helped create and then went on to pilot the nation’s first Co-Parent Court. His docket was limited to the toughest cases, those where the father had denied paternity and paternity had to be established in order to set an award. (Those who voluntarily established paternity—the majority—had their awards adjudicated by an administrative judge.) Peterson’s innovation was to offer parents the opportunity to learn co-parenting skills by participating in four training session that custodial and noncustodial parents attended separately. Then, in a final meeting with a mediator, the parents came together and were guided in crafting a tailored parenting agreement they both felt was reasonable and served the best interests of the child. These agreements then went back to the court for approval. Strikingly, two-thirds of 709 parents involved completed the classes, a very high figure for any intervention. More than half completed cooperative parenting agreements together, and all but four did so with additional assistance from the courts.

Subsequent analysis showed that participation increased visitation. When asked about the total number of hours per month the father spent or visited with their child, intervention mothers reported an increase of 64.9 hours per month on average, whereas control mothers reported an average increase of 20.5 hours per month, a marginally significant result. Furthermore, there was a significant increase in mothers’ assessments of co-parenting quality; 63% of those in the Co-Parent Court intervention reported a positive change in the quality of the co-parenting relationship as opposed to 36% of controls. Though the program did not significantly boost child support payments, the fathers who completed the program paid significantly more of the total child support owed—86% versus 69%—than those in the control group. Clearly, more experimentation is needed, but these are encouraging signs.

Helping parents build co-parenting skills may be especially important given empirical findings cited earlier showing that the receipt of child support can actually have a corrosive effect on child well-being. We cannot be sure, but it is likely that the effect is due to the fact that noncustodial parents do not usually end up in the formal system unless, or until, co-parenting has broken down. Couple conflict, and not formal child support itself, is the likely cause of harm to the child. If we want to ensure that children will benefit from participation in the formal system, improving co-parenting skills should be a central goal. Plus, letting parents have a role in setting the parenting agreement should promote compliance.

In addition, joint custody should be considered unless either parent can demonstrate good cause. Currently, in nearly a third of the states, an unmarried mother is given sole custody even if the father establishes paternity. But among divorced parents, joint custody has grown rapidly in recent years, both legal (where parents share decision-making) and physical (where children live with both parents). There is no reason why these two groups—one more likely to be middle class and white, and the other disproportionately working class or poor and nonwhite—should be treated differently. Research shows that awarding joint legal custody to unmarried parents increases child support payments by an average of $170 per year

Furthermore, if our qualitative analysis is any guide, a re-envisioned child support system can enhance the father/child bond and build fathers’ own sense that they are “providing” by making it more like in-kind support, the form of support most closely compatible with these goals. If the custodial parent agrees, we should allow informal (cash given directly to the mother) but especially in-kind (such as payment of the child care bill, or the purchase of school supplies) contributions to be recognized. Currently these are usually excluded, labelled “gifts” rather than support. Changing this rule would solve one crisis of legitimacy the child support system faces in the eyes of the men we’ve interviewed—that no one holds the mothers accountable for how the money is spent. Fathers commonly voiced fears that their contributions would be siphoned off by the mother herself, or worse, by her new boyfriend. It was common for men to say this reduced their motivation, or even made them unwilling to pay.

Allowing in-kind contributions to count may be especially important for very low earners or those with very unstable work. For such fathers, services such as household or yard maintenance, not just goods, should be allowed to count as support if the mother agrees. About two-thirds of states already have an adjustment for parenting time in their child support guidelines, an idea we can build on. The goal is to have every noncustodial parent participate in a system that obligates them to contribute but also recognizes contributions in a variety of forms. Small contributions are often viewed in low-income neighborhoods as placeholders for larger contributions that men hope to make later on, when their circumstances improve.

Finally, we should remember that the original goal of the child support system when it was founded in 1975 was to reimburse the government for welfare costs. For clients on TANF (and sometimes Medicaid), this practice continues today. The government keeps all or most of the money (or in the case of Medicaid, medical support) provided by the father, rather than passing it along to the mother and children. This sends the wrong message to noncustodial fathers. Our qualitative data confirm that fathers frequently complain that, at least in their eyes, the state “takes its cut” before their money gets to their child. The negative valence of cost recoupment is another crisis of legitimacy the system faces, and we may well entice greater cooperation and higher participation if we ended the practice.

Let’s now turn to the final criteria, ensuring that every participant is treated as a valued member of the community. Although the formal system began to transition from a sole focus on recouping welfare costs to a “family focus” as early as the mid-1990s, the program continues to treat the noncustodial parents it serves as paychecks, not parents. The primary problem is the failure to set—and enforce—parenting time agreements in cases where the parents were never married and thus there was never a divorce. (Two states already do this, and a few others offer assistance in securing parenting time.) The fathers in our study sometimes refer to the stripping of what they see as their right to parenting time as “taxation without representation.”

The current two-tiered system of child support, one that offers rights to formerly married fathers while denying them (at least de facto) to the unmarried, must end. And it might well be very productive to do so. The director of San Francisco Child Support, Karen Roye, described to me a 2004 experiment in which the local community college, the City College of San Francisco, teamed with the child support system to help 100 families. They identified a number of women who wanted to take classes but couldn’t because of childcare responsibilities and lack of money due to the failure of the noncustodial fathers to pay child support. They negotiated visitation agreements with the dads under which the fathers would take care of the kids when the mothers were in class. It was a stunning success. All of the mothers graduated with a certification or associates degree. A significant number of the dads went on to earn degrees too. Child support was paid more reliably. Several of the couples even reunited.

Finally, treating noncustodial fathers as valued members of the community will require that we make investments in their capacity to pay. Federal child support funding cannot be devoted to such purposes at present. That should change. Other innovations, such as extending the Earned Income Tax Credit, the Child Tax Credit, or both, to fathers who pay child support have gained traction. These would not only reward those who pay through the formal system, but it would increase the incentive for men to work in the formal economy.

But let’s take the opportunity to go even further, given the complex family society in which we now live. We can’t return to the 1950s. We need to take families as they are. In our society, “co-parent” should be recognized as a key social role. Judge Peterson of Minnesota’s Hennepin County has suggested that we offer “enhanced recognition of parenting” in the legal systems that adjudicate child support that would value the variety of ways in which fathers can play a role in their children’s lives. This could even involve “commitment to parenting” ceremonies, where parents who share a child could invite families and friends to witness their joint commitment to co-parent. It’s not as wild an idea as it sounds. We all know—at least if we’ve had enough sociology courses—that social norms and institutions influence behavior. We should experiment with any number of approaches such as these to see if they work.

The key to progress is abandoning the false assumption that men are indifferent to their children. Then we can design policies that build on the felt connection to a child to help fathers overcome the barriers to playing a more constructive co-parenting role. Earning respect as parents could also motivate these men to seek better jobs and behave more responsibly in other aspects of their lives. They could become the valued members of the community that they aspire to be.

I will end with a story that illustrates how even small actions can make a big difference. One problem that Peterson faced as presiding judge of the Family Court was getting the putative noncustodial fathers to show up for hearings at all. He felt that the letter the court sent was needlessly pejorative and full of legalese. When the county adopted the Co-Parent Court as part of an innovative demonstration project, he had a chance to do something about it. Families in the project’s control group continued to get the standard letter. However, he made sure those in the intervention received a different kind of message. Though the fathers in both groups were ordered to appear, the Co-Parent Court letter eliminated some of the legalese, talked about providing services, and included a welcoming, colorful brochure with photos of fathers and children. It laid out, in simple language, the next steps. What happened? According to Peterson, “Twice as many people in the intervention group came to court because we didn’t [simply] call it a paternity hearing. We said that we’re going to talk about your family.”