Reorienting U.S. Drug Policy

The nature and extent of the illegal drug problems in the United States have fundamentally changed during the past two decades; now policy needs to change as well.

The United States will soon surpass the half-million mark for drug prisoners, which is more than 10 times as many as in 1980. It is an extraordinary number, more than Western Europe locks up for all criminal offenses combined and more than the pre-Katrina population of New Orleans. How effective is this level of imprisonment in controlling drug problems? Could we get by with, say, just a quarter million locked up for drug violations?

Now is an opportune time to consider this issue. The illegal drug problem has fundamentally changed during the past two decades, in both its nature and its extent. With a few exceptions, the drug problem has stabilized and begun to improve in the United States during the past 15 years. Notably, the number of people dependent on expensive drugs such as cocaine has dropped significantly from its peak. The terrifying spike in drug-related homicides of the late 1980s has long ended. Today, we are dealing with an older, less violent, and more stable population of drug abusers. Despite these changes, the number of drug prisoners continues to increase.

Tough enforcement is supposed to drive up prices and make it more difficult to obtain drugs, and thus reduce overall drug use and the problems that it causes. Yet the evidence indicates that it has had quite limited success at reducing the supply of established mass-market drugs. Thus, even assuming that tough enforcement was an appropriate response at an earlier time, today’s situation justifies considering different policy options.

In particular, there is little reason to believe that the United States would have a noticeably more serious drug problem if it kept 250,000 fewer drug dealers under lock and key. Given the social harms that result from imprisonment as well as the considerable taxpayer tab for incarceration, there is a case to be made for working out ways to reduce the number of people in jail and prison for drug offenses.

Among affluent nations, U.S. rates of drug use are not exceptionally high by contemporary international standards. About 1 in 15 Americans aged 12 and over currently uses drugs, a much smaller figure than in, for example, Great Britain. By a wide margin, prevalence is highest among older teenagers and those in their early 20s, peaking at around 40% using within the past 12 months for high-school seniors. Most Americans who try drugs use them only a few times. If there is a typical continuing user, it is an occasional marijuana smoker who will cease to use drugs at some point during his 20s. Marijuana use in the 15- to 26year-old age group has been at high levels throughout the past three decades, but there have also been notable ups and downs. Usage rose through the 1970s, fell in the 1980s, and bounced back up in the early 1990s, but only among adolescents and very young adults.

What these data from general population surveys do not describe well are the trends in the behaviors that dominate drug-related social costs, which primarily involve drug-related crime, health consequences, premature mortality, and lost productivity. These problems are worse in the United States than they are in most other countries, and they are driven by the number of people dependent on cocaine (including crack), heroin, and methamphetamines, drugs that might collectively be called the expensive drugs to distinguish them from marijuana. Marijuana is by far the most widely used of the illicit drugs, but its use directly accounts for only about 10% of those adverse outcomes, in part because a year’s supply of marijuana costs so little that its distribution and purchase engender relatively little crime or violence.

The compulsive use of expensive drugs in the United States is a legacy of four major drug epidemics. The notion of a drug epidemic captures the fact that drug use is a learned behavior, transmitted from one person to another. Contrary to the popular image of the entrepreneurial drug pusher who hooks new addicts through aggressive salesmanship, it is now clear that almost all first experiences are the result of being offered the drug by a friend or family member. Drug use thus spreads much like a communicable disease, a metaphor familiar from marketing and new-product-adoption models. Users are “contagious,” and some of those with whom they come into contact become “infected.” Initiation of heroin, cocaine, and crack use shows much more of a classic epidemic pattern than does marijuana use, although the growth of marijuana use in the 1960s may have had epidemic features.

In an epidemic, rates of initiation (infection) in a given area rise sharply as new and highly contagious users of a drug initiate friends and peers. At least with heroin, cocaine, and crack, long-term addicts are not particularly contagious. They are often socially isolated from new users. Moreover, they usually present an unappealing picture of the consequences of addiction. In the next stage of the epidemic, initiation declines rapidly as the susceptible population shrinks, because there are fewer nonusers and/or because the drug’s reputation sours, as a result of better knowledge of the effects of a drug. The number of dependent users stabilizes and typically declines gradually.

The first modern U.S. drug epidemic involved heroin. It developed with rapid initiation in the late 1960s, primarily in a few big cities and most heavily in inner-city minority communities; the experiences of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam may have been a contributing factor. The annual number of new heroin initiates peaked in the early 1970s and then dropped by ~50% by the late 1970s and remained low until the mid 1990s. Heroin addiction (at least for those addicted in the United States rather than while in the military in Vietnam) has turned out to be a long-lived and lethal condition, as revealed in a remarkable 33-year followup of male heroin addicts admitted to the California Civil Addict Program during the years 1962–1964. Nearly half of the original addicts—284 of 581—had died by 1996–1997; of the 242 still living who were interviewed, 40% reported heroin use in the past year and 60% were unemployed.

Cocaine in powder form was the source of the second epidemic, which lasted longer and was more sharply peaked than the heroin epidemic. Initiation, which was broadly distributed across class and race, rose to a peak around 1980 and then fell sharply, by ~80% or more during the 1980s. Dependence always lags behind initiation, and cocaine use became more common in the mid-1980s as the pool of those who had experimented with the drug expanded. The number of dependent users peaked around 1988 and declined only moderately through the 1990s.

The third epidemic was of crack use. Although connected to the cocaine epidemic—crack developed as an easy-to-use form of freebase cocaine—the crack epidemic was more concentrated among minorities in inner-city communities. Its starting point varied across cities; for Los Angeles the beginning may have been 1982, whereas for Chicago it was as late as 1988. But in all cities initiation appears to have peaked within about two years and to have again left a population with a chronic and debilitating addiction.

The fourth important epidemic, of methamphetamine use, has gradually rolled two-thirds of the way across the country, from west to east, taking hold where cocaine use was less common. It had already stabilized on the West Coast by the time rapid spread began in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys; it still has not reached most of the East Coast. There have been other epidemics (for example, ecstasy use), but heroin, cocaine (including crack), and methamphetamine probably account for close to 90% of the social costs associated with illicit drugs in the United States.

What is particularly interesting is that big declines in cocaine and heroin prices (discussed below) have not triggered new epidemics. Initiation goes up when prices go down, but once a drug has acquired a bad reputation, it does not seem prone to a renewed explosion or contagious spread in use. That is a great protective factor, though presumably not eternal.

U.S. drug policies

The United States spends a lot of money on drug control. The drug czar claims that federal expenditures are $12.5 billion, but that figure excludes big items that everyone else thinks should be included, notably federal prosecution and prison costs. Excluding these figures allows the federal government to claim to roughly balance supply reduction (mostly enforcement) and demand reduction (prevention and treatment). Putting in the full list of programs might take the federal figure to more than $17 billion. State and local governments, which provide most of the policing and prison funding, probably spend even more. So across all levels of government, drug control spending may exceed $40 billion annually.

How well do the different kinds of programs work? Everyone likes the idea of preventing kids from starting drug use, but drug prevention is nothing like immunizing kids against drug abuse. The most widely implemented programs have never been shown by rigorous evaluations to have any effect on drug use, and even cutting-edge model programs that fare better in evaluation studies produce reductions in use that mostly dissipate by the end of high school. Even recognizing the historical correlation between delayed onset and reduced lifetime use, projected reductions in lifetime consumption are in the single-digit percentages. Modest effects should not be surprising. It is hard to do anything within 30 contact hours that overrides the impact of the thousands of hours that typical young people spend with peers, listening to music, watching television, and so on. The good news is that the budgetary cost of school-based prevention is low, so prevention appears to still be modestly cost-effective unless one ascribes a particularly high value to the opportunity cost of diverting classroom hours from academic subjects or volunteers’ hours from other causes.

Mass-media campaigns are notoriously difficult to evaluate because they are so diffuse; it is hard to find a control group so that one can distinguish the effects of the campaign from other factors affecting drug use. Still, it is sobering that evaluations by Westat and the Annenberg School of Communications of the federal government’s high-profile media campaign suggest that it has had no effect on drug use

Treating those with drug problems is the one kind of intervention for which there is a fairly good empirical base to judge effectiveness. About 1.1 million individuals received some kind of treatment for drug dependence or abuse in 2004, plus another 340,000 for whom alcohol was the primary substance of abuse. Federal expenditures on that amounted to about $2.4 billion; the states may add about as much again. Heroin addicts mostly get methadone, a substitute opiate. Everyone else gets, in some form, counseling. Even though the majority of clients entering treatment drop out and of those who complete their treatment more than half will relapse within five years, it is easy to make the case that the intervention is cost-effective. This comes from the fact that many of those who enter treatment, certainly those with heroin or cocaine problems, are very high-rate criminal offenders. During treatment, their drug use goes down a lot and that cuts their crime rates comparably. These crime-reducing benefits from treatment help the community as well as the patient.

It is disappointing that the number in treatment at any one time (~850,000, including 500,000 who also abused alcohol) is only a modest fraction of the 3 to 4 million who are dependent on cocaine, methamphetamine, or heroin. There are a similar number who are dependent only on marijuana, which is the single most common primary substance of abuse for those treated; however, those dependent only on marijuana are less likely to be frequent offenders or to suffer acute health harms, so the social benefits of treating them are quite different and much smaller. (Most marijuana-only users who are compelled into treatment by an arrest are low- to medium-rate users.)

Most U.S. drug efforts go to enforcing drug laws, predominantly against sellers; oddly enough, that is also true for other less punitive nations, including the Netherlands. Although eradication and crop substitution programs overseas in the source countries, primarily in the Andes, get a lot of press coverage, they account for a small share of even the federal enforcement budget, about $1 billion. More money—about $2.5 billion in 2004—is spent on interdiction: trying to seize drugs and couriers on their way into the country.

Neither source-country programs nor interdiction has much promise as a way of producing more than a transitory reduction in drug consumption in the United States. They focus on the phases of the production and distribution system at which the drugs are still cheap and easily replaced because there is plenty of land, labor, and routes available to adapt to government interventions. In addition to creating occasional transitory disruptions, interdiction (in contrast to source-country interventions such as crop eradication) has long made drug smuggling surprisingly expensive, but it has not managed to raise smugglers’ costs further in a long time.

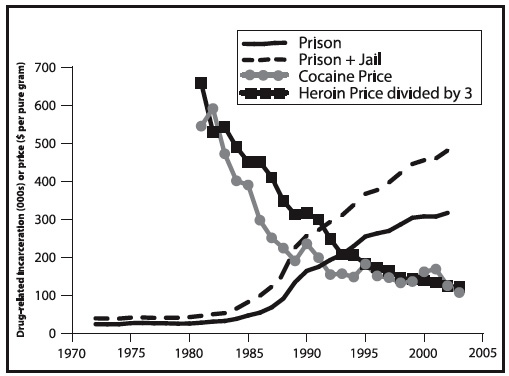

The majority of all drug control expenditures go to the enforcement of drug laws within the United States. Between 1980 and 1990, dependent drug use and violent drug markets expanded rapidly, and the number of people locked up for drug law violations increased by 210,000. Between 1990 and 2000, drug problems began to ease, but drug incarcerations increased by still another 200,000. Simply put, incarceration has risen steadily while drug use has both waxed and waned.

The great majority of those locked up are involved in drug distribution. Although a sizable minority were convicted of a drug possession charge, in confidential interviews most of them report playing some (perhaps minor) role in drug distribution; for example, they were couriers transporting (and hence possessing) large quantities or they pled down to a simple possession charge to avoid a trial.

Society locks up drug suppliers for multiple reasons. Drug sellers cause great harm because of the addiction they facilitate and the crime and disorder that their markets cause. Thus there is a retributive purpose for the imprisonment. Still, sentences can exceed what mere retribution might require. Perhaps the most infamous example is that in federal courts the possession of 5 grams of crack cocaine will generate a five-year mandatory minimum sentence, compared with a national average time served for homicide of about five years and four months, even though that $400 worth of crack is just one fifty-millionth of U.S. annual cocaine consumption, or about two weeks’ supply for one regular user.

Does tough enforcement work?

An important justification for aggressive punishment is the claim that high rates of incarceration will reduce drug use and related problems. The theory is that tough enforcement will raise the risk of drug selling. Some dealers will drop out of the business, and the remainder will require higher compensation for taking greater risks. Hence the price of drugs should rise. It should also make drug dealers more cautious and thus make it harder for customers to find them. So the central question is whether the huge increase in incarceration over the past 25 years has made drugs more expensive and/or less available.

The science of tracking trends in illicit drug prices is not for purists; there are no random samples of drug sellers or transactions. However, the broad trends apparent in the largest data sets (those stemming from law enforcement’s undercover drug buys) are confirmed by other sources, including ethnographic studies, interviews with or wire taps of dealers, and forensic analysis of the quantity of pure drug contained in packages that sell for standardized retail amounts (for example, $10 “dime bags” of heroin). During the past 25 years, the general price trends have gone more or less in the opposite direction from what would be expected (see figure). Incarceration for drug law violations (primarily pertaining to cocaine and heroin) increased 11-fold between 1980 and 2002, yet purity-adjusted cocaine and heroin prices fell by 80%. Methamphetamine prices also fell by more than 50%, although the decline was interrupted by some notable spikes. Marijuana prices unadjusted for purity rose during the 1980s and 2000s but fell during the 1990s. Declining prices in the face of higher incarceration rates does not per se contradict the presumption that tougher enforcement can reduce use by driving up prices. Other factors may have driven the price declines. Drug distributors might have been making supernormal profits in the early 1980s that were driven out over time by competition, or “learning by doing” might have improved distribution efficiency within the supply chain. Hence, it is possible that prices would have fallen still farther had it not been for the great expansion in drug law enforcement.

Ilyana Kuziemko and Steven D. Levitt published a study of this question in the Journal of Public Economics in 2004. They found that cocaine prices in 1995 were 5 to 15% higher as a result of the increases in drug punishment since 1985. That result helps save the economic logic that supply control ought to drive retail prices up, not down, but the estimated slope of the price-versus-incarceration curve is so flat that expanded incarceration appears not to have been a cost-effective tool for controlling drug use.

During that 10-year period, incarceration for drug law violations increased from 82,000 to 376,000, about two-thirds of which were cocaine offenders. Thus, to achieve the modest increase in cocaine prices, it cost an extra $6 billion a year just for incarceration (assuming a cost of $30,000 per year to house an inmate). Annual cocaine consumption then was about 300 metric tons. So even assuming an elasticity of demand as large, in absolute value, as –1, a 10% increase in price would avert only about 30 metric tons of consumption, or less than 5 kilograms per million taxpayer dollars spent on incarceration.

To put this figure in perspective, 5 kilograms is about 40 person-years of use for a heavy user. Eliminating that use by incarcerating the users would not have cost much more (40 person-years ¥ $30,000/cell-year = $1.2 million) and might also have yielded some deterrent effects; yet almost no one thinks long prison terms make sense for users who were not involved in drug distribution.

As another way to understand how meager this cost-effectiveness ratio of 5 kilograms per million dollars is, model-based estimates predicated on that same elasticity done by RAND’s Drug Policy Research Center had projected a cost-effectiveness of 27.5 kilograms per million dollars even when including arrest and adjudication costs. Yet that much larger cost-effectiveness figure was still perceived as comparing unfavorably to other control options and as being a rather expensive way to suppress drug use.

Nor is there any evidence that tougher enforcement has made cocaine or other drugs harder to get. The fraction of high-school seniors reporting that cocaine is available or readily available has been about 50% for 25 years; for 85% of respondents, the same statement remains true for marijuana.

Changing times, changing policies

With a few exceptions (notably oxycontin and methamphetamine), the drug problem in the United States has been slowly improving during the past 15 years. The number of people dependent on expensive drugs (cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine) has declined from roughly 5.1 million in 1988 to perhaps 3.8 million in 2000, the most recent year for which figures have been released. The residual drug-dependent populations are getting older; more than 50% of cocaine-related emergency department admissions are now of people over 35, compared to 20% 20 years ago. The share of those treated for heroin, cocaine, and amphetamine dependence who were over 40 rose from 13% in 1992 to 31% in 2004. Kids who started using marijuana in the late 1990s are less likely to go on to use hard drugs than were kids who started in the 1970s.

What we face now is not the problem of an explosive drug epidemic, the kind that scared the country in the 1980s when crack emerged and street markets proliferated, but rather “endemic” drug use, with stable numbers of new users each year. The substantial number of aging drug abusers cause great damage to society and to themselves, but the problem is not rapidly growing. Rather, it is slowly ebbing down to a steady state that, depending on the measure one prefers, may be on the order of half its peak.

Rising imprisonment probably made some contribution to these trends. Some of the most aggressive dealers are now behind bars; their replacements are no angels but may be both less violent and less skilled at the business. However, the discussion above raises doubts about whether incarceration accounts for much of the decline. If prices have not risen and if the drugs are just as available as before, then it is hard to see how tough enforcement against suppliers can be what explains the ends of the epidemics and the gradual but important declines in the number of people dependent on expensive drugs.

This provides an opportunity. Changed circumstances justify changed policies, but U.S. drug policies have changed only marginally as the problem has transformed. The inertia can be seen by examining why the number of prisoners keeps rising even as drug markets get smaller. Drug arrests have been flat at 1.6 million a year for 10 years, and more and more of them are for marijuana possession (almost half in 2003), which produces very few prison sentences.

Three factors drive the rise in incarceration. First, today’s drug offenders are not just older; they also have longer criminal records, exposing them to harsher sentences. Second, legal changes have made it more likely that someone arrested for drug selling will get a jail or prison sentence. Third, the declining use of parole has meant longer stays in prison for a given sentence length. On average, drug offenders who received prison sentences in state courts in 2002 were given terms of four years, of which they served about half. Is it a good thing that those being convicted are now spending more time behind bars?

Any case for cutting drug imprisonment should not pretend that prisons are bulging with first-time, nonviolent drug offenders. Most were involved in distributing drugs, and few got into prison on their first conviction; they had to work their way in. The system mostly locks up people who have caused a good deal of harm to society. Most will, when released, revert to drug use and crime. They do not tug the heart strings as innocent victims of a repressive state.

Still, would the United States really be worse off if it contented itself with 250,000 rather than 500,000 drug prisoners? This would hardly be going soft on drugs. It would still be a lot tougher than the Reagan administration ever was. It would ensure that the United States still maintained a comfortable lead over any other Western nation in its toughness toward drug dealers. Furthermore, incarcerating fewer total prisoners need not mean that they all get out earlier. The minority who are very violent or unusually dangerous in other ways may be getting appropriate sentences, and with less pressure on prison space, they might serve more of their sentences. Deemphasizing sheer quantity of drug incarceration could usefully be complemented by greater efforts to target that incarceration more effectively.

There is no magic formula behind this suggestion to halve drug incarceration as opposed to cutting it by one-third or two-thirds. The point is simply that dramatic reductions in incarceration are possible without entering uncharted waters of permissiveness, and the expansion to today’s unprecedented levels of incarceration seems to have made little contribution to the reduction in U.S. drug problems.

Drug treatment as an alternative to incarceration has become a standard response, more talked about than implemented. Drug courts that use judges to cajole and compel offenders to enter and remain in treatment are one tool, but they account for a modest fraction of drug-involved offenders because the screening criteria are restrictive, excluding those with long records. Proposition 36 in California, which ensured that most of those arrested for drug possession for the first time were not incarcerated, seems to have been reasonably successful in at least cutting the number jailed without raising crime rates or any other indicator one worries about. These, though, are interventions that deal with less serious offenders, most of whom will only go to local jail rather than to prison.

A more important change would be to impose shorter sentences and then use University of California at Los Angeles Professor Mark Kleiman’s innovation of coerced abstinence as a way of keeping them reasonably clean while on parole. Coerced abstinence simply means that the criminal justice system does what the citizens assume it is doing already, namely detecting drug use early via frequent drug testing and providing short and immediate sanctions when the probationer or parolee tests positive. The small amount of research on this kind of program suggests that it works as designed, but it is hard to implement and needs to be tested in tougher populations, such as released parolees.

A democracy should be reluctant to deprive its citizens of liberty, a reluctance reinforced by the facts that imprisonment falls disproportionately on poor minority communities and that many U.S. prisons are nasty and brutalizing institutions. Further, there is growing evidence that the high incarceration rates have serious consequences for communities. A recent study suggests that differences in black and white incarceration rates may explain most of the sevenfold higher rate of HIV among black males as compared to white males. If locking up typical dealers for two years rather than one has minimal effect on the availability and use of dangerous drugs, then a freedom-loving society should be reluctant to do it.

Yet we are left with an enforcement system that runs on automatic, locking up increasing numbers on a faded rationale despite the high economic and social costs of incarceration and its apparently quite modest effects on drug use. Truly “solving” the nation’s drug problem, with its multiple causes, is beyond the reach of any existing intervention or strategy. But that should not prevent decisionmakers from realizing that money can be saved and justice improved by simply cutting in half the number of people locked up for drug offenses.