When Youth Are Experts in the Field

Increasing the value and relevance of research on youth mental health requires incorporating the lived experience of children, youth, and their families in every step of the scientific process.

Usually, reports from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) exclusively involve members of the research community and policymakers—stakeholders who are traditionally considered “experts in the field.” But in 2020, NASEM’s Board on Children, Youth, and Families (BCYF) took a very different approach before publishing its consensus report, Promoting Positive Adolescent Health Behaviors and Outcomes. Because the report explores the current landscape of adolescent risk behavior and makes recommendations for more supportive research, policies, and practices, the authoring committee recognized the need for input from adolescents to ensure the practicality and tangible impact of their final recommendations. This required changing how the committee and staff worked and added complexity to the process—and it also immensely increased the value and relevance of the report.

Incorporating youth insight also opened the door for the report to be disseminated to young people across the country. BCYF staff developed a special summary to present the report’s main findings to a youth audience and then worked with youth members of the University of Michigan’s MyVoice program to get feedback on the draft. Through this experience, BCYF staff and committee members learned much more than if they had only consulted the traditional experts in the field.

The next draft of the highlights was sent for additional feedback to over 1,000 youth aged 14–24 through MyVoice’s weekly text message poll. To engage directly with youth, NASEM staff held a public listening session with three young speakers who presented to nearly 200 viewers. For the BCYF staff, this feedback was, at times, brutally honest and humbling. For example, in a question about how the report highlights could be improved to speak directly to the needs of youth, one 17-year-old responded, “The ‘healthy risks’ part almost seems patronizing. No at-risk kid is going to decide not to drive drunk or bully someone because a pamphlet told them to ‘try new foods!’ instead.”

Through encounters like this, staff gained perspective not only on the concerns of youth, but how to reach this audience. Engaging youth in the research process is particularly necessary because the experiences of young people today are very unlike those of generations before them. This generation is more racially and ethnically diverse, as well as better educated. And they have grown up in a world where smartphones and the internet are ubiquitous, making their experience of being an adolescent markedly different from youth of even 20 years ago.

Working with youth on this report profoundly influenced the BCYF staff and committee members. For research related to children, youth, and families to be impactful, it must also be relevant and responsive to the diverse lived experiences of young people themselves. To accomplish this, research must incorporate the personal knowledge about the world gained through firsthand accounts of everyday events rather than through representations constructed by other people. Meaningfully incorporating youth perspectives makes research more effective in that outcomes respond to the real needs of young people. This, in turn, can lead to policies that are also more reflective of their real needs.

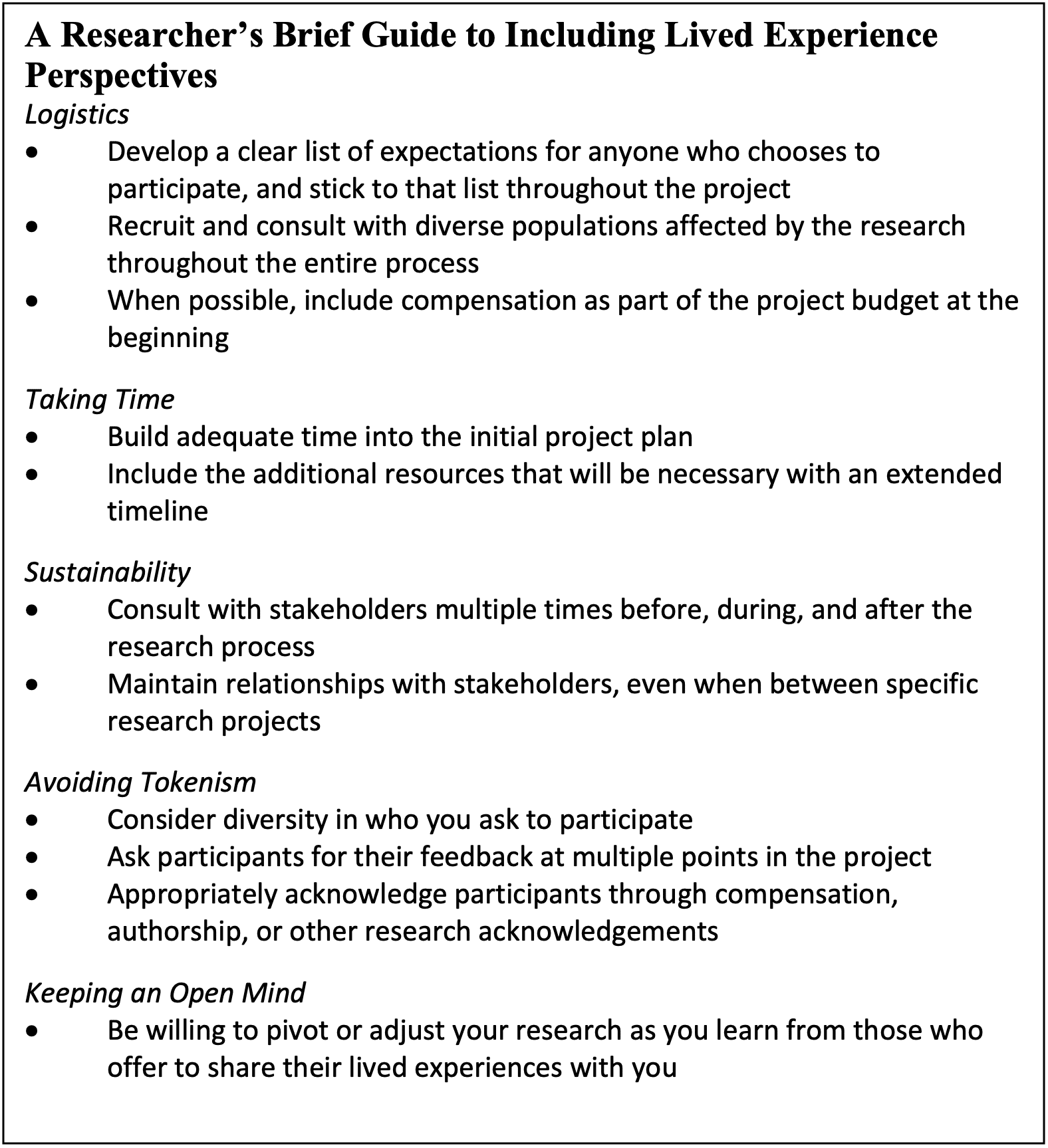

To be sure, incorporating youth voices and others’ lived experience into the research process often introduces new challenges. Project timelines can lengthen, making research more expensive. It can create new or unforeseen logistical issues. And it can challenge underlying research assumptions, which may require rethinking approaches.

Recognizing this as an essential part of our work, BCYF has made it a goal to better incorporate the lived experience of children, youth, and their families in every step of the scientific process. This includes developing and reviewing proposals, writing research questions, collecting and analyzing data, and disseminating and communicating findings and their implications.

We have realized this goal in several ways. Two recent consensus studies focused on adolescence (The Promise of Adolescenceand Promoting Positive Adolescent Health Behaviors and Outcomes) incorporated youth voices through questionnaires and surveys, public information-gathering panel discussions, reflection panels, review of final products, and dissemination events and activities. BCYF’s Forum for Children’s Well-Being (the Forum) has also made a concerted effort to expand the inclusion of youth and family voices in its work. And a BCYF project focused on developing coping tools for youth worked with family support partners to obtain external feedback during the development of the tools. Engaging directly with youth and families has helped us better fulfill our mission and increased the impact of our work.

How the Lived Experience Changes Research—for the Better

“All these programs are formed by adults, and I think it’s really important that those adults don’t assume they know what kids want those programs to be. Lots of programs assume you don’t want to know everything, and keep the worst stuff to the side.”

Abby, 14, Michigan

While researchers may think they know the right questions to ask, youth can help focus research on what is truly relevant. Including youth as part of the question design phase can also reduce the risk of exacerbating harmful biases and assumptions about youth and their experiences. For example, when BCYF staff invited youth climate activists to participate in a meeting related to the impact of climate change on youth mental health, the young activists spoke about their desire to study environmental science in college. Initially, BCYF staff and other meeting participants assumed this stemmed from a genuine interest in climate science and a desire to work on an issue about which they were passionate. However, as the conversations progressed, it became clear that their drive came instead from their fear and anxiety about climate change. One high school student shared that while she wished she could study English literature in college, she felt obligated to study environmental science so that she could better protect her own future. For the adult participants at the meeting, hearing this underscored the importance of addressing ecoanxiety in youth and created a greater sense of urgency for more research on the topic.

Involving youth and families in the development of research questions can also reveal research areas that are currently neglected, posing interesting questions that researchers may not have previously considered. At a workshop hosted by the Forum focused on ways to support students returning to in-person learning after COVID-19 closures, a youth participant shared that for some LGBTQ+ students, returning to school may mean a return to bullying from peers. While this was not a perspective that was initially considered in the workshop planning, many of the other workshop speakers, including teachers and educators, shifted their comments to respond to that very real fear and began to consider the implications for their own students. What this anecdote highlights is that it is not enough to simply have youth in the room; these informants must be diverse and bring a wide variety of experiences, perspectives, and backgrounds to bear on the research process.

With all research, it’s paramount to ensure final research products are usable and acceptable to end users, but this is particularly relevant in research on youth well-being. When researchers work without a lived experience perspective, they are prone to miss crucial elements in interpretation of study results, intervention design, or policy implications. Despite their best efforts, researchers may be limited by their own experiences and fail to anticipate how youth and families will respond to their products.

BCYF recently brought together a group of experts to help develop interactive, web-based tools to promote emotional well-being and resilience in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This crisis is unlike anything youth have experienced before: it interrupted their daily routines, isolated them from their social networks, and, in some cases, elevated their roles as caretakers and income earners in their families. Furthermore, the pandemic occurred against a backdrop of social unrest across the country that was driving awareness and advocacy efforts among youth. Recognizing that their own experiences and existing academic research provided a limited perspective on this uniquely contemporary issue, the research leaders asked several family support partners—parents and family members who are trained to advocate for children with mental health concerns—to provide feedback throughout the development process. For nearly six months, the project director met weekly with family support partners to review drafts of the products and provide comments. This process was invaluable in moving the tools from an academic exercise into more usable products with relatable, nuanced storylines that reflected the diverse experiences of youth during the pandemic.

In another example, the committee writing The Promise of Adolescence held an open session panel where six adolescents responded to a series of questions related to their own experiences and shared reflections on how to engage youth authentically. They helped the committee identify three specific priority areas where adults and systems could better support them: providing support during the transition to adulthood, providing adequate resources for mental health, and respectfully and authentically engaging adolescents in decisions that affect them. This experience, and the information gathered, made the committee realize youth wanted more interaction. A second youth panel was invited to comment on the committee’s final recommendations before publication to ensure they were reflective of young people’s real needs and experiences. Based on their feedback, the committee revised the report to emphasize its recommendations related to health care for youth.

There is much to be gained in asking youth and family members for their perspectives, and researchers must be prepared to have their assumptions challenged and to be told they are wrong. As a youth speaker told one NASEM committee, “You’ve been through more experiences, yes, which is completely true. And you totally earned your stripes through that, but your experience is much different than what we are going through now.” Although it can be difficult to hear this, these perspectives offer a reality check on the academic perspective, which may contain assumptions that don’t match the real experiences of children, youth, and families. Listening and learning from youth and their families can be humbling and, though it may change the direction of a project, it will ultimately increase and expand the impact of the work.

Ensuring Youth Engagement Throughout the Research Process

“How do youth make other people listen? I often think older people discredit the ideas of youth just because they are young and perceived as inexperienced.”

19-year-old male from MyVoice

Incorporating youths’ diverse lived experiences into research requires special preparations: extra time and accounting for the complexity that comes with adding new steps and new voices to decisionmaking. BCYF staff have found it helpful to prepare for longer timelines at the start of the project, rather than trying to adjust for them throughout. Research funders should be aware of the importance of adding adequate time and structure when reviewing grant proposals.

When such activities are planned, compensation for participants should be considered in the original project budget. Lived experience participants may need to take time away from work or pay for childcare to participate in research. Compensating them for their time not only lessens these burdens, but it also acknowledges their contributions to the research process and makes it more likely that they will participate in the project. Although many organizations may not presently be able to offer financial compensation due to organizational or grantor restrictions, building such funds into future project and program budgets can help to create a sustainable and mutually beneficial process for incorporating lived experience.

Compensation is only part of the picture for participants; time commitment is another. Asking youth and families to participate in research is asking them to add to their already extensive list of responsibilities, including school, work, and childcare. It is crucial to be up-front about expectations to allow them to decide if and how they might be able to participate in projects.

Flexibility is also important, and researchers may need to make themselves available outside of normal work hours. For example, when conducting a series of interviews with youth and parents from across the country for the Forum’s fall 2020 workshop, BCYF staff offered to meet with the interviewees during the evening as well as on the weekends, and in doing so they were able to hear from a broader range of voices. Clips from this series of interviews were used for an introductory video for the workshop, which set the tone for the other panel discussions and prompted the speakers to respond to real concerns.

Finally, researchers must be intentional about creating environments where participants feel comfortable and valued. This often requires adapting research-centric or academic language and avoiding jargon. It also means respecting the perspectives offered by youth and family members, just as those from other academics or researchers are respected. Youth will be more inclined to participate when they believe their voice will truly be listened to, and researchers are more likely to be successful when they uphold their commitment of elevating youth voices.

Disseminating Research Findings and Communicating Their Implications

Finding ways to acknowledge and include youth and family participants when research findings are disseminated will help ensure that they remain engaged and part of the conversation. To the extent possible, mentioning these participants in traditional research acknowledgements in publications or in some other manner—for example, all the family advocates are listed on the NASEM project webpage as advisors to the group of experts—provides a strong symbol that their work and expertise are valued. Additionally, opportunities for these contributors to share in presentations, authorship, and other occasions to present and discuss results helps them become true partners in the work. One of the family advocates who helped created the online tools described above participated in a conference presentation with several of the experts appointed to the project.

An Ongoing Effort

“We can make sure that youth are acknowledged and that we are heard in the research process, so it’s not just an adult perspective on what youth life is like and what youth experiences and problems are.”

Jalynn, 16, Oklahoma

The lessons and examples described in this paper represent just a first step towards increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion for youth and families in scientific research. This ongoing effort requires a level of humility and gratitude on the part of researchers—humility to accept that they may miss key components in research without guidance from youth and their families, and gratitude for the willingness of lived experience participants to share their knowledge and better inform research. It requires youth and family members to be generous with their time and open with their perspectives. Lastly, it requires an acknowledgement from everyone that for research to truly impact youth and families, it must include them from the very beginning. For BCYF, there will always be more to learn while we work toward ensuring that all our work is driven by and benefits the populations we serve. Moving forward, BCYF staff will reflect on these lessons and continue to elevate lived experiences in future projects. We invite others involved in scientific research—both in this field and in others—to join us.

“It’s always best … to actually be a part of the conversation and be doing something. Or being part of a conversation and learning something.”

Jayde, 20, Florida