William Utermohlen

William Utermohlen was born in south Philadelphia in 1933. He studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts from 1951 to 1957 and on the G.I. bill at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, England, from 1957 to 1958. In 1962 he settled in London, and in 1967 he received his first important London show at the Marlborough Gallery. Depictions of his life and friends in London form intimate themes that thread throughout his body of work.

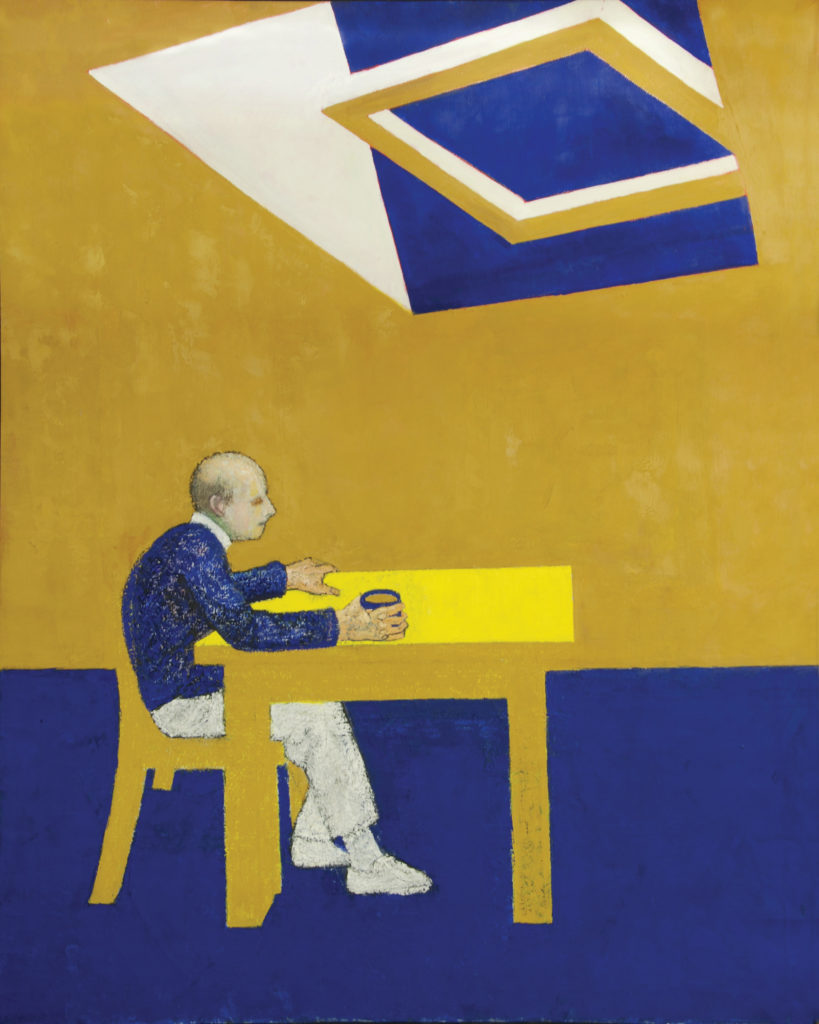

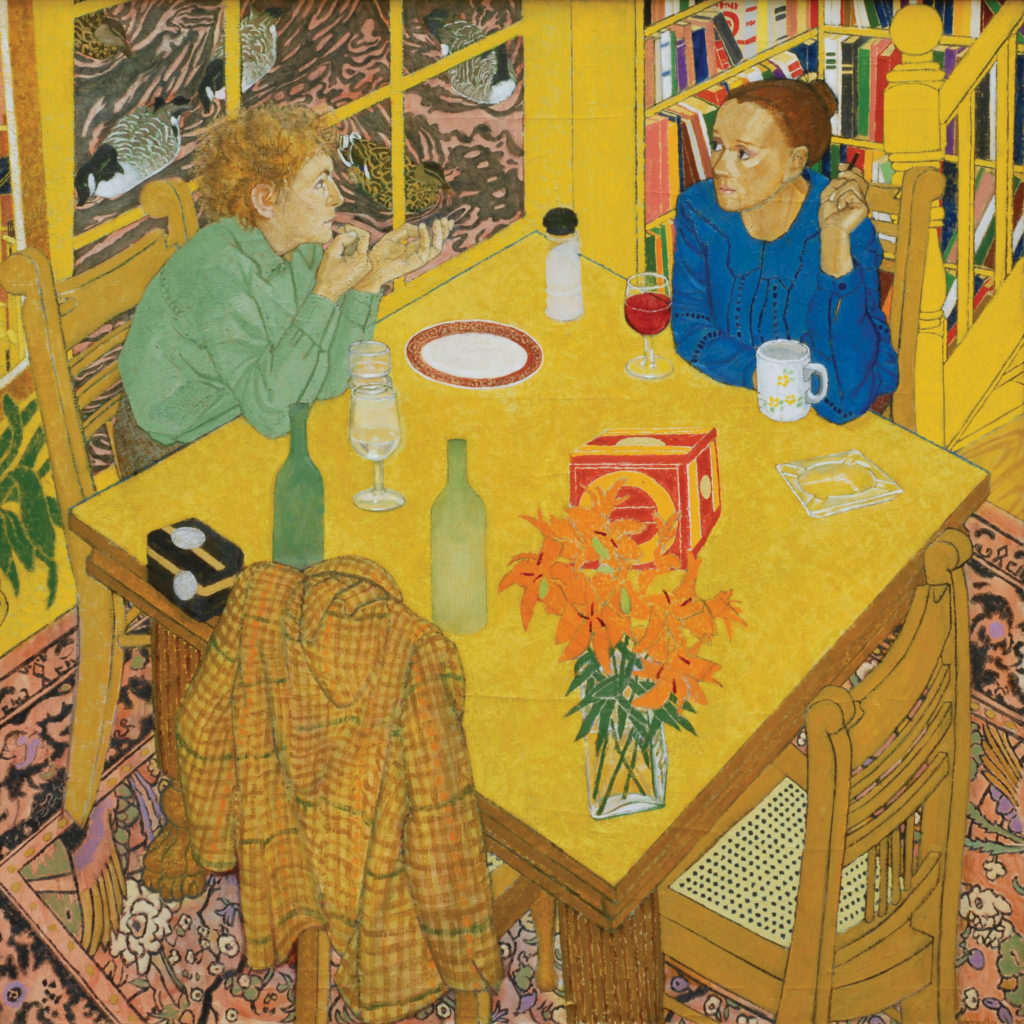

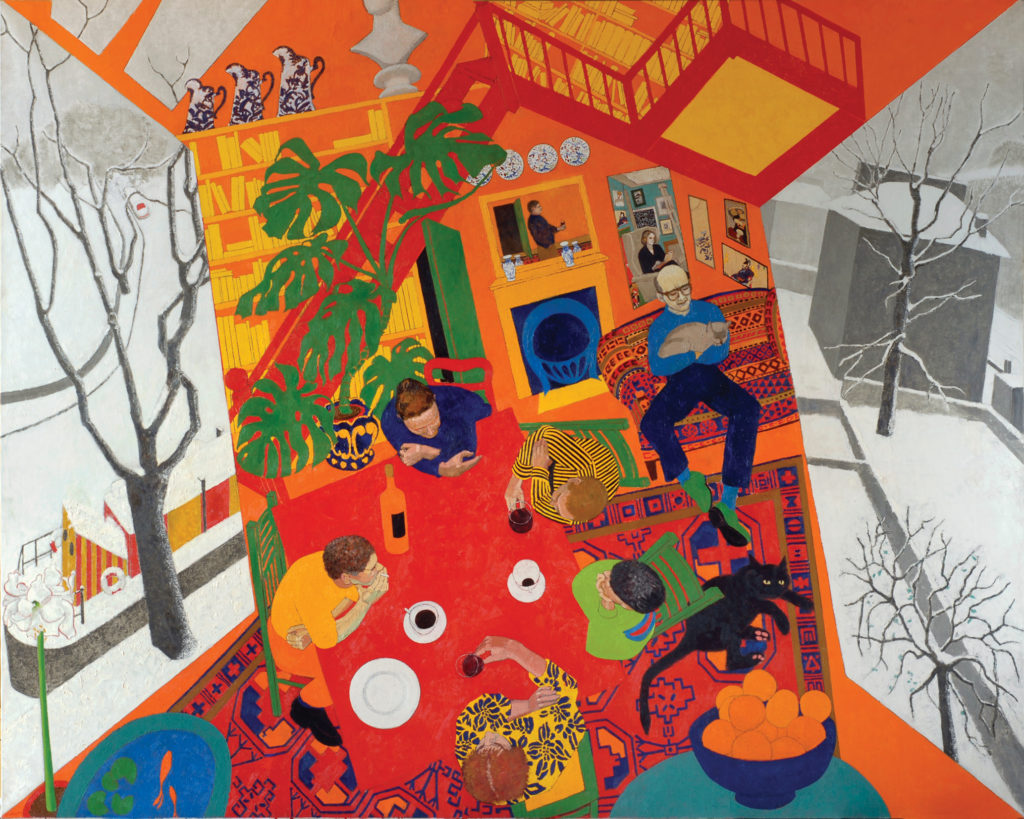

In 1995 Utermohlen was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Signs of his illness are retrospectively apparent in the work of the early 1990s, notably in the Conversation Pieces, which depict the warmth and happiness of his relationship with his wife, art historian Patricia Redmond, and his rich companionship with friends. But as gallerist and longtime friend Chris Boïcos noted, “Signs of the disease are made apparent in the shifting perceptions of space, objects, and people. They are premonitions of a new world of silence and sensory deprivation about to close in on the artist.”

Utermolen’s work has become a standard representation of the use of visual imagery to depict internal psychological states of someone with AD. Although he wasn’t engaged in art therapy, he did work with UK neuropsychologist Sebastian Crutch, who recognized the value of artistic expression and the arts as windows into mental and psychological processes of which one might not even be conscious. As Crutch noted, “his painting is more eloquent than anything he could have said with words.”

Because Utermohlen was a practicing artist for most of his lifetime, his neural pathways were conditioned to express through brush, paint, and hand. His artwork exhibits a disintegration of form into more affective and primitive symbolic states. His artistic rendering became less complicated and less defended. One can see in his work a progressive loss of identity or sense of self.

Utermohlen’s portraits show a deterioration of facial characteristics, which may be indicative of the loss of facial recognition that is often symptomatic of AD. Over time his self-portraits become less cohesive and more abstract, and they show a loss of orientation and specificity, a growing spatial confusion and distortion. Utermohlen gradually integrates less color in his work, which might mean less affect or feelings, and less of a sense of awareness and being in the world, which is typical of people with progressive neurodegenerative disease. Utermohlen’s paintings are a powerful representation of a growing health crisis.

Dementia affects 5% of the US population over age 65, and two-third of those people have Alzheimer’s disease. Loss of memory is only one of many symptoms. The disease can also erode language capacity and limit patients’ ability to articulate what they are experiencing. This leads to a deterioration of social connectedness and to feelings of isolation and abandonment. Although William Utermohlen did not formally participate in art therapy, his work suggests that art therapy interventions might be valuable for those with AD.

As a healthcare practitioner and academician whose research interests focus on the neuroscientific basis of creativity and the neurological mechanisms that underscore the intervention strategies in the profession of art therapy, I am familiar with the importance of understanding the relationship between health and disease and its impact on psychological, emotional, and social functioning. Artistic expression, both in the process of creation and in the products that emerge, offers a path of communication and a window into the psyche that may be more effective than words alone.

Individuals suffering from overwhelming stress, neurological problems, trauma, depression, abuse, and mental illness often find it difficult to describe their experience in words. Painting or drawing provides a channel for patients to express their thoughts and feelings more clearly and directly. Art therapists are trained to understand the art products that are created in the process of psychotherapy, and how the formal elements of artwork are representative of the internal workings of the person. This makes it easier, and faster, for the person to express what is bothering them. Many patients find artistic creations to be less personally threatening than words and are therefore able to be more transparent and objective. The art product stands as a symbol for the self, which allows the person, with the help of the trained therapist, to see themselves more clearly. And knowing that art can also help others to understand what one is experiencing can help reduce the feelings of isolation and loneliness that accompany AD. As researchers continue their frustrating quest to develop a medical cure or treatment for AD, we must remember that innovations in the care of AD patients can make a difference now.

—Juliet King is associate professor of art therapy at George Washington University and adjunct associate professor in the Department of Neurology at Indiana University School of Medicine

Images courtesy of Chris Boïcos Fine Arts.