What Fish Oil Pills Are Hiding

DAVID SCHLEIFER

ALISON FAIRBROTHER

One Woman’s Quest to Save the Chesapeake Bay from the Dietary Supplement Industry

Julie Vanderslice thought fish were disgusting. She didn’t like to look at them. She didn’t like to smell them. Julie lived with her mother, Pat, on Cobb Island, a small Maryland community an hour south and a world away from Washington, D.C. Her neighbors practically lived on their boats in warm weather, fishing for stripers in the Chesa-peake Bay or gizzard shad in shallow creeks shaded by sycamores. Julie had grown up on five acres of woodland in Accokeek, Maryland, across the Potomac River from Mount Vernon, George Washington’s plantation home. The Potomac River wetlands in Piscataway Park were a five-minute bike ride away, on land the federal government had kept wild to preserve the view from Washington’s estate. Her four brothers and three sisters kept chickens, guinea pigs, dogs, cats, and a tame raccoon. They went fishing in the Bay as often as they could. But Julie preferred interacting with the natural world from inside, on a comfortable couch in her living room, where she read with the windows open so she could catch the briny smell of the Bay. “No books about anything slimy or smelly, thank you!” she told her family at holidays.

So it was with some playfulness that Pat’s friend Ray showed up on Julie’s doorstep one afternoon in the summer of 2010 to present her with a book called The Most Important Fish in the Sea. Ray was an avid recreational fisherman, who lived ten miles up the coast on one of the countless tiny inlets of the Chesapeake. The Chesapeake Bay has 11,684 miles of shoreline—more than the entire west coast of the United States; the watershed comprises 64,000 square miles.

“It’s about menhaden, small forage fish that grow up in the Chesapeake and migrate along the Atlantic coast. You’ll love it,” he told her, chuckling as he handed over the book. “But seriously, maybe you’ll be moved by it,” he said, his tone changing. “It says that when John Smith came here in the seventeenth century, there were so many menhaden in the Bay that he could catch them with a frying pan.”

Julie shuddered at the image of so many slippery little fish.

“Now the menhaden are vanishing,” Ray said. “I want you to read this book. I want Delegate Murphy to read this book. And I want the two of you to do something about it.”

Julie was the district liaison for Delegate Peter Murphy, a Democrat representing Charles County in the Maryland House of Delegates. She had started working for Murphy in February 2009 as a photographic intern, tasked with documenting his speeches and meetings with constituents. In her early fifties, Julie was older than the average intern. For ten years, she had sold women’s cosmetics and men’s fragrances at a Washington, D.C. branch of Woodward & Lothrop, until the legendary southern department store chain liquidated in 1995. She had moved to Texas to take a job at another department store in Houston, but it hadn’t felt right. Julie was a Marylander. She needed to live by the Chesapeake Bay. Working in local politics reconnected her to her community, and it wasn’t long before Murphy asked her to join his staff full-time. Now, she worked in his office in La Plata, the county seat, and attended events in the delegate’s stead—like the dedication of a new volunteer firehouse on Cobb Island or the La Plata Warriors high school softball games.

Julie picked up the menhaden book one summer afternoon, pretty sure she wouldn’t make it past the first chapter. She examined the cover, which featured a photo of a small silvery fish with a wide, gaping mouth and a distinctive circular mark behind its eye. “This is the most important fish in the sea?” Julie muttered to herself. She settled back into her sofa and sighed. Her mother was out at a church event, probably chattering away with Ray. Connected to the main-land by a narrow steel-girder bridge, Cobb Island was a tiny spit of land less than a mile long where the Potomac River meets the Wicomico. The island’s population was barely over 1,100. What else was there to do? She turned to the first page and began to read.

For the next few days, The Most Important Fish in the Sea followed Julie wherever she went. She read it out on the porch while listening to the gently rolling waters of Neale Sound, which separated Cobb Island from the mainland. She read it in bed, struggling to keep her eyes open so she could fit in just one more chapter. She finished the book one afternoon just as Pat came through the screen door, arms laden with a bag full of groceries. Pat found Julie standing in the middle of the living room, angrily clutching the book. Pat was dumbfounded. “You don’t like to pick crab meat out of a crab!” she said. “You wear water-shoes at the beach! Here you are all worked up over menhaden!”

Menhaden are a critical link in the Atlantic food chain, and the Chesapeake Bay is critical to the fish’s lifecycle. Menhaden eggs hatch year round in the open ocean, and the young fish swim into the Chesa-peake to grow in the warm, brackish waters. Also known colloquially as bunker, pogies, or alewifes, they are the staple food for many commercially important predator fish, including striped bass, bluefish, and weakfish, which are harvested along the coast in a dozen different states, as well as for sharks, dolphins, and blue whales. Ospreys, loons, and seagulls scoop menhaden from the top of the water column, where the fish ball together in tight rust-colored schools. As schools of menhaden swim, they eat tiny plankton and algae. As a result of their diet, menhaden are full of nutrient-rich oils. They are so oily that when ravaged by a school of bluefish, for example, menhaden will leave a sheen of oil in their wake.

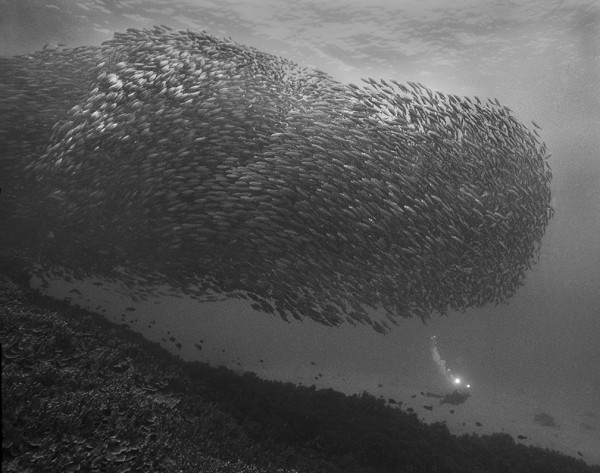

Wayne Levin

Imagine seeing what you think is a coral reef, only to realize that there is movement within the shape and that it is actually a massive school of fish. That is what happened to Wayne Levin as he swam in Hawaii’s Kealakekua Bay on his way to photograph dolphins. The fish he encountered were akule, the Hawaiian name for big-eyed scad. In the years that followed he developed a fascination with the beauty and synchronicity of these schools of akule, and he spent a decade capturing them in thousands of photographs.

Akule have been bountiful in Hawaii for centuries. Easy to see when gathering in the shallows, the dense schools form patterns, like unfurling scrolls, then suddenly contract into a vortex before unfurling again and moving on. In his introduction to Akule (2010, Editions Limited), a collection of Levin’s photos, Thomas Farber describes a photo session: “What transpired was a dance, dialogue, or courtship of and with the akule….Sometimes, for instance, he faced away from them, then slowly turned, and instead of moving away the school would…come towards him. Or, as he advanced, the school would open, forming a tunnel for him. Entering, he’d be engulfed in thousands of fish.”

Wayne Levin has photographed numerous aspects of the underwater world: sea life, surfers, canoe paddlers, divers, swimmers, shipwrecks, seascapes, and aquariums. After a decade of photographing fish schools, he turned from sea to sky, and flocks of birds have been his recent subject. His photographs are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego; The Honolulu Museum of Art; the Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, Honolulu; and the Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Virginia. His work has been published in Aperture, American Photographer, Camera Arts, Day in the Life of Hawaii, Photo Japan, and most recently LensWork. His books include Through a Liquid Mirror (1997, Editions Limited), and Other Oceans (2001, University of Hawaii Press). Visit his website at waynelevinimages.com.

Alana Quinn

WAYNE LEVIN, Column of Akule, 2000.

WAYNE LEVIN, Filming Akule, 2006.

For hundreds of years, people living along the Atlantic Coast caught menhaden for their oils. Some scholars say the word menhaden likely derives from an Algonquian word for fertilizer. Pre-colonial Native Americans buried whole menhaden in their cornfields to nourish their crops. They may have taught the Pilgrims to do so, too.

The colonists took things a step further. Beginning in the eighteenth century, factories along the East Coast specialized in cooking menhaden in giant vats to separate their nutrient-rich oil from their protein—the former for use as fertilizer and the latter for animal feed. Dozens of menhaden “reduction” factories once dotted the shoreline from Maine to Florida, belching a foul, fishy smell into the air.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, menhaden fishermen hauled thousands of pounds of net by hand from small boats, coordinating their movements with call-and-response songs derived from African-American spirituals. But everything changed in the 1950s with the introduction of hydraulic vacuum pumps, which enabled many millions of menhaden to be sucked out of the ocean each day—so many fish that companies had to purchase carrier ships with giant holds below deck to ferry the menhaden to shore. According to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration records, in the past sixty years, the reduction industry has fished 47 billion pounds of menhaden out of the Atlantic and 70 billion pounds out of the Gulf of Mexico.

Reduction factories that couldn’t keep up went out of business, eliminating the factory noises and fishy smells, much to the relief of the growing number of wealthy home-owners purchasing seaside homes. By 2006, every last company had been bought out, consolidated, or pushed out of business—except for a single conglomerate called Omega Protein, which operates a factory in Reedville, a tiny Virginia town halfway up the length of the Chesapeake Bay. A former petroleum company headquartered in Houston and once owned by the Bush family, Omega Protein continues to sell protein-rich fishmeal for aquaculture, animal feed for factory farms, menhaden oil for fertilizer, and purified menhaden oil, which is full of omega-3 fatty acids, as a nutritional supplement. For the majority of the last thirty years, the Reedville port has landed more fish than any other port in the continental United States by volume.

The company also owns two factories on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, which grind up and process Gulf menhaden, the Atlantic menhaden’s faster-growing cousin. But Hurricane Katrina in 2005, followed by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, forced Omega Protein to rely increasingly on Atlantic menhaden to make up for their damaged factories and shortened fishing seasons in the Gulf—much to the dismay of fishermen and residents along the Atlantic coast.

These days, on a normal morning in Reedville, Virginia, a spotter pilot climbs into his plane just after sunrise to scour the Chesapeake and Atlantic coastal waters, searching for reddish-brown splotches of menhaden. When he spots them, the pilot signals to ship captains, who surround the school with a net, draw it close, and vacuum the entire school into the ship’s hold.

Julie Vanderslice had never seen the menhaden boats or spotter planes, but she was horrified by the description of the ocean carnage documented in The Most Important Fish in the Sea. The author, H. Bruce Franklin, is an acclaimed scholar of American history and culture at Rutgers University, who has written treatises on everything from Herman Melville to the Vietnam War. But he is also a former deckhand who fishes several times a week in Raritan Bay, between New Jersey and Staten Island.

Julie was riveted by a passage in which Franklin describes going fishing one day for weakfish in his neighbor’s boat. Weakfish are long, floppy fish that feed lower in the water column than bluefish, which thrash about on top. Franklin’s neighbor angled his boat toward a chaotic flock of gulls screaming and pounding the air with their wings. The birds were diving into the water and fighting off muscular bluefish to be the first to reach a school of menhaden. The two men had a feeling that weakfish would be lurking below the school of menhaden, attempting to pick off fish from the bottom. But before Franklin and his neighbor could reach the school, one of Omega Protein’s ships sped past, set a purse seine around the menhaden, and used a vacuum pump to suck up hundreds of thousands of fish and all the bluefish and weakfish that had been feeding on them. For days afterward, Franklin observed, there were hardly any fish at all in Raritan Bay.

That moment compelled Franklin to uncover the damage Omega Protein was doing up and down the coast. The company’s annual harvest of between a quarter and a half billion pounds of menhaden had effects far beyond depleting the once-plentiful schools of little fish. Scientists and environmental advocates contended that by vacuuming up menhaden for fishmeal and fertilizer, Omega Protein was pulling the linchpin out of the Atlantic ecosystem: starving predator fish, marine mammals, and birds; suffocating sea plants on the ocean floor; and pushing an entire ocean to the brink of collapse. Despite being published by a small environmental press, The Most Important Fish in the Sea was lauded in the Washington Post, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Baltimore Sun, and the journal Science. The New York Times discussed it on its opinion pages, citing dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay and Long Island Sound where too few menhaden were left to filter algae out of the water.

After finishing the book, Julie couldn’t get menhaden out of her head. She had to get the book into Delegate Murphy’s hands. She bought a second copy, prepared a two-page summary, and plotted her strategy.

Julie didn’t see the delegate every day because she worked in his district office rather than in Annapolis, the country’s oldest state capitol in continuous legislative use. But that summer, Delegate Murphy was campaigning for re-election and was often closer to home. He was scheduled to make an appearance at a local farmer’s market in Waldorf a few weeks after Julie had finished the book. Waldorf was at the northern edge of Murphy’s district, close enough to Washington that the weekly farmers market would be crowded with an evening rush of commuters on their way home from D.C. But in the late afternoon, the delegate’s staff, decked out in yellow Peter Murphy T-shirts, nearly outnumbered the shoppers browsing for flowers and honey.

Delegate Murphy was at ease chatting with neighbors and shaking hands with constituents. He was tall and thin, with salt-and-pepper hair and lively eyes. Julie recognized his trademark campaign uniform: a blue polo shirt tucked neatly into slacks. He had been a science teacher before entering state politics, and he had a deep, calming voice. As a grandfather to two young children, he knew how to captivate a skeptical audience with a good story. Julie recalled the day she first met him, at a sparsely attended town hall meeting at Piccowaxen Middle School. He struck her immediately as a genuine, thoughtful man on the right side of the issues she cared about. Several months later, she heard that Delegate Murphy was speaking at the Democratic Club on Cobb Island and made a point to attend. Afterward, she waited for him in the receiving line. When it was her turn to speak, Julie asked if he was hiring.

WAYNE LEVIN, Ring of Akule, 2000.

Just a few short years later, Julie felt comfortable enough with Delegate Murphy to propose a mission. Mustering her courage as a band warmed up at the other end of the market, Julie seized her moment. “Delegate Murphy, you have to read this!” she said, pushing the book into his hands. “There’s this fish called menhaden that you’ve never heard of. One company in Virginia is vacuuming millions of them out of the Chesapeake Bay, taking menhaden out of the mouths of striped bass and osprey and bluefish and dolphins and all the other fish and animals that rely on them for nutrients. This is why recreational fishermen are always complaining about how hungry the striped bass are! This is why our Bay ecosystem is so unhinged! One company is taking away all our menhaden,” she declared. “We have to stop them.”

Delegate Murphy peered at her with a trace of a smile. “I’ll read it, Julie,” he said.

For months afterward, Julie stayed late at the office, reading everything she could find about menhaden. She learned that every state along the Atlantic Coast had banned menhaden fishing in state waters—except Virginia, where Omega Protein’s Reedville plant was based, and North Carolina, where a reduction factory had recently closed. (North Carolina would ban menhaden reduction fishing in 2012.) The largest slice of Omega Protein’s catch came from Virginia’s ocean waters and from the state’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay, preventing those fish from swimming north into Maryland’s section of the Bay and south into the Atlantic to populate the shores of fourteen other states along the coast.

Beyond the Chesapeake, Omega Protein’s Virginia-based fleet could pull as many menhaden as they wanted from federal waters, designated as everything between three and two hundred miles offshore, from Maine to Florida. Virginia was a voting member of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC), the agency that governs East Coast fisheries. But the ASMFC had never taken any steps to limit the amount of fish Omega Protein could lawfully catch along the Atlantic coast. Virginia’s legislators happened to be flush with campaign contributions from Omega Protein.

Julie clicked through articles on fisherman’s forums and coastal newspapers from every eastern state. She read testimony from citizens who described how the decimation of the menhaden population in the Chesapeake and in federal waters had affected the entire Atlantic seaboard. Bird watchers claimed that seabirds were suffering from lack of menhaden. Recreational fishermen cited scrawny bass and bluefish, and wondered whether they were lacking protein-packed menhaden meals. Biologists cut the stomachs of gamefish and found fewer and fewer menhaden inside. Whale watchers drove their boats farther out to sea in search of blue whales, which used to breach near the shore, surfacing open-mouthed upon oily schools of menhaden. The dead zones in the Chesapeake Bay grew larger, and some environmentalists connected the dots: menhaden were no longer plentiful enough to filter the water as they had in the past. In 2010, the ASMFC estimated that the menhaden population had declined to a record low, and was nearly 90 percent smaller than it had been twenty-five years ago.

Of course, Omega Protein had its own experts on staff, whose estimates better suited the company’s business interests. At a public hearing in Virginia about the menhaden fishery, Omega Protein spotter pilot Cecil Dameron said, “I’ve flown 42,000 miles looking at menhaden…. I’m here to tell you that the menhaden stock is in better shape than it was twenty years ago, thirty years ago. There’s more fish.”

One humid evening at the end of August, Delegate Murphy held a pre-election fundraiser and rally in his backyard, a grassy spot that sloped down toward the Potomac River. Former Senator Paul Sarbanes stopped by, and campaign staffers brought homemade noodle salads, cheeses, and a country ham. With the election less than two months away, the staff was working overtime, but they had hit their fundraising goal for the day. At the end of the event, as constituents headed to their cars, Delegate Murphy found Julie sitting at one of the collapsible tables littered with used napkins and glasses of melting ice. Julie was accustomed to standing for hours when she worked in the department store, but there was something about fundraising that made her feel like putting her feet up.

WAYNE LEVIN, Circling Akule, 2000.

WAYNE LEVIN, Rainbow Runners Hunting Akule, 2001.

“Great work tonight, Peter,” she said, wearily raising her glass to him. Julie always called him Delegate Murphy in public. But between the two of them, at the end of a long summer afternoon, it was just Peter.

He toasted and sat down beside her. Campaign staffers were clearing wilted chrysanthemums from the tables and stripping off plastic tablecloths. Peter and Julie looked across the lawn at the blue-gray Potomac as the sun began to dip in the sky.

“Listen,” he said. “I think I have an idea for a bill we could do.”

“On?”

“On menhaden.”

Julie put her drink down so quickly it sloshed onto the sticky tablecloth. She leaned forward in disbelief.

“We’ve got to try doing something about this,” Peter said.

Julie put her hand to her mouth and shook her head. “Menhaden reduction fishing has been banned in Maryland since 1931. Omega Protein is in Virginia. How could a bill in Maryland affect fishing there?”

“We don’t have any control over Virginia’s fishing industry, but we can control what’s sold in our state. I got to thinking: what if we introduced a bill that would stop the sale of products made with menhaden?”

“Do you think it would ever pass?” Julie asked.

“If we did a bill, it would first come before the Environmental Matters Committee. I think the chair of the committee would be amenable. At least we can put it out there and let people talk about it.”

Julie was overcome. He didn’t have to tell her how unusual this was. The impetus for new legislation didn’t often come from former interns—or from their fishermen neighbors.

“But I don’t know if we can win this on the environmental issues alone. What about the sport fishermen? Can we get them to come to the hearing?” Peter asked.

Julie began jotting notes on a napkin.

“Can you find out how many tourism dollars Maryland is losing because the striped bass are going hungry?”

“I’ll get in touch with the sport fishermen’s association and see if I can look up the numbers. And I’ll try to find out which companies are distributing products made from menhaden. It’s mostly fertilizer and animal feed. A little of it goes into fish oil pills, too.”

“The funny thing is, my own doctor told me to take fish oil pills a few years ago,” Peter said. He patted Julie’s shoulder and stood to wave to the last of his constituents as they disappeared down the driveway.

Doctors like Peter’s wouldn’t have recommended fish oil if a Danish doctor named Jörn Dyerberg hadn’t taken a trip across Greenland in 1970. Dyerberg and his colleagues, Hans Olaf Bang and Aase Brondum Nielsen, traveled from village to village by dogsled, poking inhabitants with syringes. They were trying to figure out why the Inuit had such a low incidence of heart disease despite eating mostly seal meat and fatty fish. Dyerberg and his team concluded that Inuit blood had a remarkably high concentration of certain types of polyunsaturated fatty acids, a finding that turned heads in the scientific community when it was published in The Lancet in 1971. The researchers argued that those polyunsaturated fatty acids originated in the fish that the Inuit ate and hypothesized that the fatty acids protected against cardiovascular disease. Those polyunsaturated fatty acids eventually came to be known as omega-3 fatty acids.

Other therapeutic properties of fish oil had been recognized long before Dyerberg’s expedition. During World War I, Edward and May Mellanby, a husband-and-wife team of nutrition scientists, found that it cured rickets, a crippling disease that had left generations of European and American children incapacitated, with soft bones, weak joints, and seizures. (The Mellanbys’ research was an improvement on the earlier work of Dr. Francis Glisson of Cambridge University, who, in 1650, advised that children with rickets should be tied up and hung from the ceiling to straighten their crooked limbs and improve their short statures.)

The Mellanbys tested their theories on animals instead of children. In their lab at King’s College for Women in London, in 1914, they raised a litter of puppies on nothing but oat porridge and watched each one come down with rickets. Several daily spoonfuls of cod liver oil reversed the rickets in a matter of weeks. Edward Mellanby was awarded a knighthood for their discovery. Although May had been an equal partner in the research, she wasn’t accorded the equivalent honor. A biochemist at the University of Wisconsin named Elmer McCollum read the Mellanbys’ research and isolated the anti-rachitic substance in the oil, which eventually came to be called vitamin D. McCollum had already isolated vitamin A in cod-liver oil, as well as vitamin B, which he later figured out was, in fact, a group of several substances. McCollum actually preferred the term “accessory food factor” rather than “vitamin.” He initially used letters instead of names because he hadn’t quite figured out the structures of the molecules he had isolated.

WAYNE LEVIN, School of Hellers Barracuda, 1999.

Soon, mothers were dosing their children daily with cod liver oil, a practice that continued for decades. Peter Murphy, who grew up in the 1950s, remembered being forced to swallow the stuff. The pale brown liquid stank like rotten fish, and he would struggle not to gag. Oil-filled capsules eventually supplanted the thick, foul liquid, and cheap menhaden replaced dwindling cod as the source of the oil. Meanwhile, following Dyerberg’s research into the Inuit diet, studies proliferated about the effects of omega-3 fatty acids—which originate in algae and travel up the food chain to forage fish like menhaden and on into the predator fish that eat them.

In 2002, the American Heart Association reviewed 119 of these studies and concluded that omega-3s could reduce the incidence of heart attack, stroke, and death in patients with heart disease. The AHA insisted omega-3s probably had no benefit for healthy people and suggested that eating fish, flax, walnuts, or other foods containing omega-3s was “preferable” to taking supplements. They warned that fish and fish oil pills could contain mercury, PCBs, dioxins, and other environmental contaminants. Nonetheless, they cautiously suggested that patients with heart disease “could consider supplements” in consultation with their doctors.

Americans did more than just “consider” supplements. In 2001, sales of fish oil pills were only $100 million. A 2009 Forbes story called fish oil “one supplement that works.” By 2011, sales topped $1.1 billion. Studies piled up suggesting that omega-3s and fish oil could do everything from reducing blood pressure and systemic inflammation to improving cognition, relieving depression, and even helping autistic children. Omega Protein was making most of its money turning menhaden into fertilizer and livestock feed for tasteless tilapia and factory-farmed chicken. But dietary supplements made for better public relations than animal feed. They put a friendlier, human face on the business, a face Peter and Julie were about to meet.

On a warm afternoon in March 2011, the twenty-four members of the Maryland House of Delegates Environmental Matters Committee filed into the legislature and took their seats. Delegate Murphy sat at the front of the room next to H. Bruce Franklin, author of The Most Important Fish in the Sea, who had traveled from New Jersey to testify at the hearing. Julie Vanderslice chose a spot in the packed gallery, with her neighbor Ray, who brought his copy of Franklin’s book in hopes of getting it signed. Julie brought her own copy, which she had bought already signed, but which she hoped Franklin would inscribe with a more personal message.

The Environmental Matters Committee was the first stop for Delegate Murphy’s legislation. The committee would either endorse the bill for review by the full House of Delegates, strike it down immediately, or send the bill limping back to Peter Murphy’s desk for further review—in which case, it might take years for menhaden to receive another audience with Maryland legislators. If the bill made it to the full House of Delegates, however, it might quickly be taken up for a vote before summer recess. If it passed the House, it was on to the Maryland Senate and, finally, to the Governor’s desk for signature before it became law. It could be voted down at any step along the way, and Julie knew there was a real chance the bill would never make it out of committee.

Julie had heard that Omega Protein’s lobbyists had been swarming the Capitol, taking dozens of meetings with delegates, and that the lobbyists had brought Omega Protein’s unionized fishermen with them. There was nothing like the threat of job loss to derail an environmental bill. Julie bit her thumb and surveyed the gallery.

To her right, rows of seats were filled with a few recreational anglers, conservationists, and scientists, whom Delegate Murphy’s legislative aide had invited to the hearing, but Julie didn’t see representatives from any of the region’s environmental organizations, like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation or the League of Conservation Voters. Delegate Murphy had called Julie on a Sunday to ask her to ask those organizations to submit letters in support of the bill. That type of outreach was not part of her job as district liaison, but she was happy to do it. While the organizations did support the bill in writing, none of them sent anyone to the hearing in person.

Instead, the seats were filled with fishermen from Omega Protein, who wore matching yellow shirts and sat quietly while the vice president of their local union, in a pinstripe suit, leaned over a row of chairs and spoke to them in a hushed voice. At the far side of the room, Candy Thomson, outdoors reporter at The Baltimore Sun, began jotting notes into her pad.

“We’re now going to move to House Bill 1142,” said Democratic Delegate Maggie McIntosh, chair of the Environmental Matters Committee.

As Delegate Murphy spoke, Julie shifted nervously in her seat. The legislators looked confused. She thought she saw one of them riffle through the stack of papers in front of her, as if to remind himself what a menhaden was. Julie wondered how many had even bothered to read the bill before the hearing. But Delegate Murphy knew the talking points backward and forward: the menhaden reduction industry had taken 47 billion pounds of menhaden out of the Atlantic Ocean since 1950. Omega Protein landed more fish, pound for pound, than any other operation in the continental United States. There had never been a limit on the amount of menhaden Omega Protein could legally fish using the pumps that vacuumed entire schools from the sea.

“This bill simply comes out and says that we as a state will no longer participate, regardless of the reason, in the decline of this fish,” he told the committee.

After Peter Murphy finished his opening statement, he and Bruce Franklin began taking questions. One of the delegates held up a letter from the Virginia State Senate. “It says that this industry goes back to the nineteenth century and that the plant this bill targets has been in operation for nearly a hundred years and that some employees are fourth-generation menhaden harvesters.” As she spoke, she paged through letters from the union that represented some of those harvesters and a list of products made from menhaden. “I don’t understand why we would interrupt an industry that has this kind of history, that will affect so many people. In this economy, I think this is the wrong time to take such a drastic approach to this issue.”

Delegate Murphy nodded. “We in Maryland, and particularly in Southern Maryland, grew tobacco for a lot longer than a hundred years,” he said, “but when we realized it was the wrong crop, and that it was killing people, we switched over to other alternatives. And we’re doing that to this day. What we’re saying with this is there are alternatives. You don’t have to fish this fish. This particular company, which happens to be in Virginia, does have alternatives to produce the same products.” He continued, “We have a company here in Maryland that produces the same omega-3 proteins and vitamins, and it uses algae. It grows and harvests algae. And that’s a sustainable resource.”

WAYNE LEVIN, Amberjacks Under a School of Akule, 2007.

WAYNE LEVIN, Great Barracuda Surrounded by Akule, 2002.

Another delegate, his hands clasped in front of him, addressed the chamber. “I’m sympathetic to saving this resource and to managing this resource appropriately,” he said. But, he explained, he been contacted by one of his constituents, a grandmother whose grandson Austin suffered from what she called “a rare life-threatening illness.” Glancing down at his laptop, he began reading a letter from this worried grandmother. “There is a bill due to be discussed regarding the menhaden fish. These fish supply the omega oils so vital to the Omegaven product that supplies children like Austin with necessary fats through their IV lines. Many children would have died due to liver failure from traditional soy-based fats had these omega-3s in these fish not been discovered. Can you please contact someone from the powers that be in the Maryland government and tell them not to put an end to the use of these fish and their life-sustaining oils.” The delegate closed his laptop. “This is a question from one of my constituents on a life-threatening issue. Can one of the experts address that issue?”

Bruce Franklin tried to explain that there are other sources of omega-3 besides menhaden. Delegate Murphy stepped in and offered to amend the bill to exempt pharmaceutical-grade products. But it was too late. Less than an hour after it had begun, the hearing was over. Delegate Murphy withdrew the bill for “summer study” rather than see it voted down—a likely indicator that the bill would not resurface before the legislature anytime soon, if ever. Delegate McIntosh turned to the next bill on the day’s schedule, and Omega Protein’s spokesperson and lead scientist left the gallery, smiling.

Julie turned to Ray, who was sitting beside her, angrily gripping his copy of The Most Important Fish in the Sea. She wanted to console him but felt uncertain how to begin. “Your fishermen buddies seem ready to riot in the streets,” Julie said uncertainly, gesturing at the anglers who were huddled together as they walked stiffly toward the foyer. “That story about the kid who’d die without his menhaden oil—that came out of nowhere.”

She looked again at the text of the bill. “A person may not manufacture, sell, or distribute a product or product component obtained from the reduction of an Atlantic menhaden.” It was exactly the kind of forward-thinking bill Maryland needed, and it would have sent a message to the other Atlantic states that menhaden were important enough to fight for. It had been her first real step toward making policy, but now she felt crushed by the legislature’s complete lack of will to preserve one of Maryland’s most significant natural resources. It seemed to her the delegates had acted without any attempt to understand the magnitude of the problem or the benefits of the proposed solution.

All Julie wanted to do was head back down to Cobb Island, stand on the dock, and feel the evening breeze on her face. Instead, she had to drive into the humid chaos of Washington, D.C., to spend two days sightseeing with her sister and her nephews. All weekend long, as her family traipsed from the Lincoln Memorial to the National Gallery to Ford’s Theater, she thought about what had gone wrong at the hearing. Had she and Delegate Murphy aimed too high with their bill? Did the committee members understand the complexity of the ecosystem that menhaden sustained? Even when the facts and figures are clear, sometimes a good story is too compelling. What politician could choose an oily fish over a sick child?

Barely a year after the Environmental Matters Committee hearing in Annapolis, the luster of fish oil pills began to fade. In 2010, environmental advocates Benson Chiles and Chris Manthey tested for toxic contaminants in fish oil supplements from a variety of manufacturers and found polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, in many of the pills. PCBs, a group of compounds once widely used in coolant fluids and industrial lubricants, were banned in the 1970s because they decreased human liver function, caused skin ailments, and caused liver and bile duct cancers. PCBs don’t easily break down in the environment; they remain in waterways like those that empty into the Chesapeake Bay, where they get absorbed by the algae and plankton eaten by fish like menhaden.

WAYNE LEVIN, Pattern of Akule, 2002.

WAYNE LEVIN, Akule Tornado, 2000.

The test results led Chiles and Manthey to file a lawsuit, under California’s Proposition 65, that named supplement manufacturers Omega Protein and Solgar as well as retailers like CVS and GNC for failing to provide adequate warnings to consumers that the fish oil pills they were swallowing with their morning coffee contained unsafe levels of PCBs. In February 2012, Chiles and Manthey reached a settlement with some manufacturers and the trade association that represents them, called the Global Organization for EPA and DHA Omega-3s (GOED), which agreed on higher safety standards for contaminants in fish oil pills.

Meanwhile, in July 2012, The New England Journal of Medicine published a study that assessed whether fish oil pills could help prevent cardiovascular disease in people with diabetes. Of the 6,281 diabetics in the study who took the pills, the same number had heart attacks and strokes as those in the placebo group. Nearly the same number died. Were all those fish-scented burps for naught? A Forbes story asked: “Fish oil or snake oil?”

In September 2012, The Journal of the American Medical Association published even worse news. A team of Greek researchers had analyzed every previous study of omega-3 supplements and cardiovascular disease, and found that omega-3 supplementation did not save lives, prevent heart attacks, or prevent strokes. GOED, the fish oil trade association, was predictably displeased. Its executive director told a supplement industry trade journal, “Given the flawed design of this meta-analysis…, GOED disputes the findings and urges consumers to continue taking omega-3 products.” But the scientific evidence was mounting: not only were fish oil pills full of dangerous chemicals, but they probably weren’t doing much to prevent heart disease, either.

Why did these pills look so promising in 2001 and not great by 2012? The American Heart Association had always favored dietary sources of omega-3s, like fish and nuts, over pills. Jackie Bosch, a scientist at McMaster University and an author of The New England Journal of Medicine study, speculated that now that people with diabetes and heart disease take so many other medicines—statins, diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, and handfuls of other pills—the effect of fish oil may be too marginal to show any measurable benefit.

Julie wasn’t surprised when she heard about the lawsuit. She knew menhaden could soak up chemical contaminants in the waterways. She read news reports about the recent studies on fish oil pills with interest and wondered whether they would give her and Delegate Murphy any ammunition for future efforts to limit the sale of menhaden products in their state. Neither had forgotten about the lowly menhaden.

Delegate Murphy had developed the habit of searching the dietary supplements aisle each time he went to the drug-store, turning the heavy bottles of fish oil capsules in his hands and reading the ingredients. None of the bottles ever listed menhaden. Despite the settlement in the California lawsuit, fish oil manufacturers were not required—and are still not required—to label the types of fish included in supplements, making it difficult for consumers to know whether they contained menhaden oil or not. But Delegate Murphy had made it clear he wasn’t ready to take up the menhaden issue again without a reasonable chance of success. Julie didn’t press him on his decision.

Then in December 2012, increasing public pressure about the decline of menhaden finally led to a change. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission voted to reduce the harvest of menhaden by 20 percent from previous levels, a regulation that would go into effect during the 2013 fishing season. It was the first time any restriction had been placed on the menhaden industry’s operations in the Atlantic, although the cut was far less severe than independent scientists had recommended. To safeguard the menhaden’s ability to spawn without undue pressure from the industry’s pumps and nets, scientists had advised reducing the harvest by 50 to 75 percent of current catch levels. Delegate Murphy and Julie knew 20 percent wasn’t nearly enough to bring the menhaden stocks back up to support the health of the Bay. But it was a start. They liked to think their bill had moved the conversation forward a little bit.

That Christmas, down on Cobb Island, Julie was putting stamps on envelopes for her family’s annual holiday recipe exchange. She addressed one to her brother Jerry in Arkansas. He didn’t usually come back east for the holidays, preferring to fly home in the summer when his sons could fish for croakers off the dock that ran out into the Wicomico River behind Julie’s house. Jerry worked for Tyson Foods, selling chicken to restaurant chains. Julie had asked him once if Tyson fed their chickens with menhaden meal, and Jerry had admitted he wasn’t sure. Whatever the factory-farmed chickens ate, Julie wasn’t taking any chances. After the hearing on the menhaden bill, she became a vegetarian. For Christmas, she was sending her family recipes for eggless egg salad and an easy bean soup.

When she finished sealing the last envelope, Julie pulled on a turtleneck sweater and grabbed her winter coat for the short walk up to the post office. The sky was a pale, dull gray, and it smelled of snow. She had recently read Omega Protein’s latest report to its investors, and as she trudged slowly toward Cobb Island Road, a word from the text popped into her mind. Company executives had repeatedly made the point that Omega Protein was “diversifying.” They had purchased a California-based dietary supplement supplier that sourced pills that didn’t use fish products. They had begun talking about proteins that could be extracted from dairy and turned into nutritional capsules. Could it be that Omega Protein had begun to see the writing on the wall? Maybe they were starting to realize that the menhaden supply was not unlimited—and that advocates like Julie wouldn’t let them take every last one.

As she passed the Cobb Island pier, a few seagulls were circling mesh crab traps that had been abandoned on the dock—traps that brimmed with blue crabs in the summer-time. Julie pulled her coat closer around her against the chill. She thought ahead to the summer months, when the traps would be baited with menhaden and checked every few hours by local families, and the ice cream parlor would open to serve the seasonal tourists. By the end of summer, Omega Protein would be winding down its fishing season, and the company would likely have 20 percent less fish in their industrial-sized cookers than they did the year before. Would that be enough to help the striped bass and the osprey and the humpback whales? Julie wondered. And the thousands of fishermen whose livelihoods depended upon pulling healthy fish from the Chesapeake Bay? And the families up and down the coast who brought those fish home to eat?

Julie had done a lot of waiting in her time. She had waited her whole life to find a job like the one she had with Delegate Murphy. She had waited for the delegate to get excited about the menhaden. When their bill failed, she had waited for the ASMFC to pass regulations protecting the menhaden. Now she would have to wait a little longer to find out whether the ASMFC’s first effort at limiting the fishery would enable the menhaden population to recover. But there are two kinds of waiting, Julie thought. There’s the kind where you have no agency, and then there’s the kind where you are at the edge of your seat, ready to act at a moment’s notice. Julie felt she could act. And so could Ray, Delegate Murphy, Bruce Franklin, and the sport fishermen, who now cared even more about the oily little menhaden. For now, at least until the end of the fishing season, that had to be enough. They would just have to wait and see.

David Schleifer (david.schleifer@gmail.com) is a senior research associate at Public Agenda, a nonpartisan, nonprofit research and engagement organization. Alison Fairbrother (alison@publictrustproject.org) is the executive director of the Public Trust Project.