Universities Should Set the Standard in COVID-19 Data Reporting

To understand how the novel coronavirus behaves and how it is spread, universities should voluntarily adopt formal, rigorous standards for gathering and reporting COVID-19 test data.

Universities are leading centers of COVID-19 research and are deeply engaged in national response efforts. Although other congregate settings, such as prisons and nursing homes, possess the ability to track and regulate their residents, universities—thanks to their esteemed social position and mission of education and advancing knowledge—are perhaps best positioned and most capable of studying how mitigation policies can affect coronavirus spread.

Beyond researching effective prevention and treatment measures, some universities have rolled out comprehensive COVID-19 testing programs. These programs play an important role in identifying positive COVID cases and protecting students and adjacent populations. At the height of the pandemic, some schools tested students up to three times per week, and some continue to test all on-campus faculty and students, or certain faculty and student populations, regularly. Often, students are also required to report their daily symptoms.

With such programs, universities often account for an outsized share of the rapid ramp-up of local COVID-19 testing. Counties with universities experienced an increase in COVID-19 testing per capita following the start of instruction in late summer 2021. A study from the US Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a 150% increase in testing among persons aged 18 to 22 in August 2020, “possibly related to new screening practices as colleges and universities reopened.”

The data collected by research universities—repeated, granular, and with high rates of asymptomatic testing—provide a rare window into COVID cases and transmission that can be used to assess the effectiveness of countermeasures.

However, despite their success in implementing comprehensive testing programs, universities’ reporting of these testing data is insufficient, both for community transparency and for the advancement of scientists’ understanding of the virus and its spread. Current data provided in universities’ public “COVID dashboards” may misrepresent the state of coronavirus on campuses and hamper the ability of researchers studying such data to provide reliable insights into the impact of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) on coronavirus spread.

Despite their success in implementing comprehensive testing programs, universities’ reporting of these testing data is insufficient, both for community transparency and for the advancement of scientists’ understanding of the virus and its spread.

There are no state or national standards for how—or whether—universities should report their COVID-19 data, but grassroots efforts have sprung up. We Rate COVID Dashboards was founded by two Yale University professors, Cary Gross and Howard Foreman, to bridge this lack of guidance. Although currently inactive, throughout the 2020–2021 academic year the website and associated Twitter account rated universities’ online COVID dashboards, assigning them a letter grade based on criteria including readability, accessibility, timeliness, and data content. In defining important metrics, offering dashboard templates, hosting a webinar, and perhaps most importantly publicly scrutinizing different universities’ performance, We Rate COVID Dashboards likely inspired positive change and improved the state of data disclosure among universities.

That said, efforts such as We Rate COVID Dashboards don’t have the resources or capacity to rate all universities. In the end, it rated 369 universities—remarkable for a small initiative but representing less than 10% of higher education institutions in the United States. And the initiative has remained inactive since April 2021, despite the rise of the Delta COVID-19 variant as well as dramatically increased populations on campus at many schools. This period has also included requirements that some employees come to campus, which may have increased the potential for breakthrough infections.

All of these observations point to an opportunity for universities to set a standard for reporting COVID-19 testing data. Given the unique position of universities in society and the continued lack of understanding of asymptomatic or vaccinated “silent spread,” this standard would help with tracking spread and identifying measures to effectively limit it. To depict universities’ on-campus COVID-19 situation transparently and accurately, we recommend this standard include three types of information.

First, we recommend universities publish daily time-series data on 1) asymptomatic and symptomatic tests; 2) asymptomatic and symptomatic positive cases; and 3) their population (of students, faculty, staff, and others) coming to campus. With these data, it is possible to calculate the true positive test rate and incidence. What’s more, consistent reporting of these data would allow researchers to better compare the viral spread across different universities, as well as the potential “superspreading” impact of universities within their own communities and beyond.

Second, we recommend that universities publish a timeline of their evolving reopening and mitigation strategies. To advance scientific understanding of the causal relationship between policies and spread, the changing incidence and positive test rates must be linked with concurrent NPIs, including reopening strategies, distancing policies, mask mandates, and enhanced cleaning and ventilation practices.

Consistent reporting of these data would allow researchers to better compare the viral spread across different universities, as well as the potential “superspreading” impact of universities within their own communities and beyond.

Currently, this relationship is impossible to ascertain, due to a lack of data on both policies and testing. Although the College Crisis Initiative (C2i) at Davidson College maintains a dataset on college reopening strategies, it provides only a single, stationary classification for the fall 2020 semester. In many cases, this does not adequately represent reopening timelines. For example, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill brought students to campus on August 3, 2020, began in-person instruction on August 10, identified hundreds of coronavirus cases within the week, and shifted to remote learning on August 19. C2i distills the fall 2020 semester into “fully online, at least some students allowed on campus.” C2i has no data on later semesters nor on the implementation of other NPIs. As it currently stands, the ability to assess the causal impact of different policies and mitigation strategies on viral spread at UNC Chapel Hill is contingent on a New York Times article documenting the school’s changing strategies.

Third, we recommend that universities add numerical data on their campus community vaccination status, including dates of vaccination and with what vaccine, to their COVID dashboards. In addition to these data, we recommend that universities continue widespread asymptomatic testing—particularly those universities that previously ramped up their capacity and may now not be using such testing.

To ascertain the status of universities’ COVID data reporting, we collected data (on August 11, 2021) from a subset of the nation’s top research universities: the 64 public and private US members of the Association of American Universities (AAU). Given their resources, prestige, and research focus, as well as external pressures to pioneer coronavirus testing and transparent data presentation, we hypothesized these universities would collect and report the most data, presenting a “gold standard” for other schools and congregate institutions to follow.

However, we found that none of these institutions publicly report the time series data needed for calculating the critical measures of incidence and positive test rate. These shortcomings can be divided into three categories.

This lack of population data limits our ability to estimate incidence or the number of new cases per 100,000 people.

First, these universities’ reported data do not track the number of people visiting campus on a regular basis, whether that be students in on-campus housing or members of the off-campus community members regularly attending campus for courses, maintenance and administrative work, day care facilities, or otherwise. This lack of population data limits our ability to estimate incidence or the number of new cases per 100,000 people. In the absence of on-campus population data, several researchers studying the role of universities in COVID spread used county-level data. Other researchers used current enrollment as a proxy for on-campus presence, despite variation in school policies resulting in a large portion of students being both absent from campus and even relocating to other cities during COVID during the period of their study.

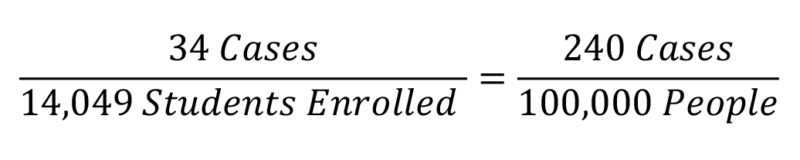

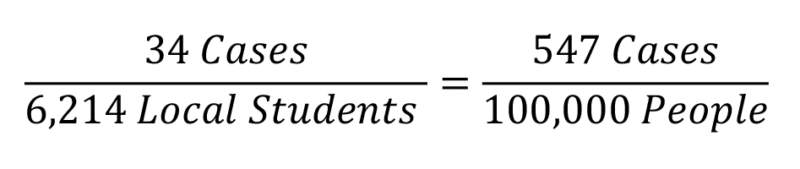

The following example from Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, illustrates how using current enrollment rather than a more accurate measure of on-campus presence results in biased estimates of incidence. Using CMU’s total enrollment, we would calculate a weekly incidence of:

However, for a given week in the fall 2020 semester, the university predicted that only 6,214 students were residing in the local Pittsburgh area, resulting in a significantly higher incidence:

It is unlikely that all of the students living in Pittsburgh were coming to campus on a daily, or perhaps even weekly, basis, given that the majority of classes were entirely online. This suggests the true incidence may be even higher.

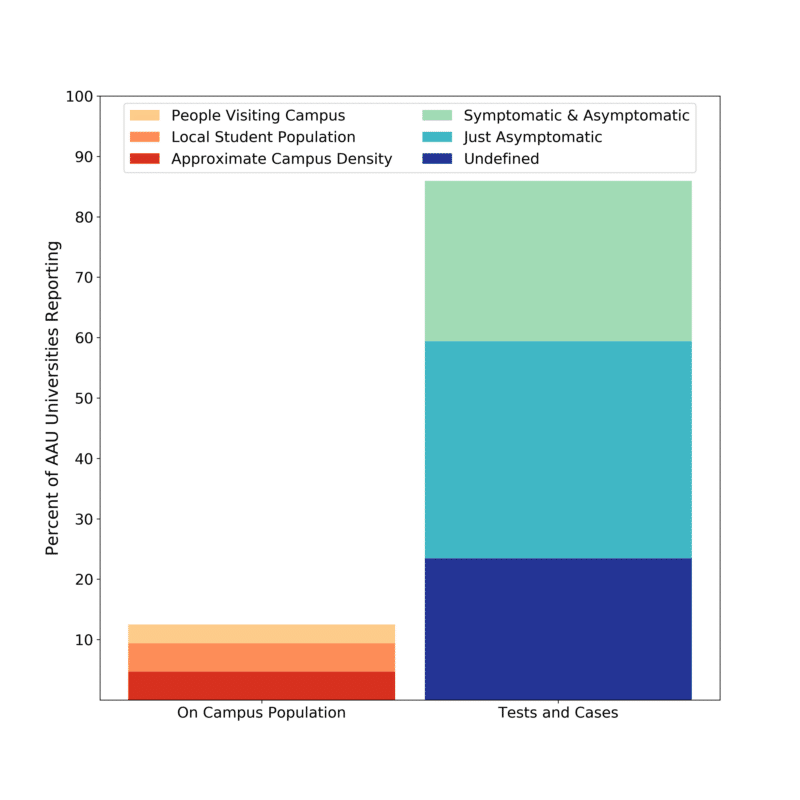

Of the 64 universities we sampled, 88% provided no on-campus population data at all, whether current or from past semesters. Three provided an approximate campus density. Another three provided an approximate number of students living on or around campus, and two provided the number of people visiting campus per semester (see Figure 1).

12% of the sampled universities published on-campus population data, falling into three subcategories of different comprehension: universities were assigned to the most comprehensive category and not double-counted.

85% of the universities published data on COVID-19 tests and cases; however, only 26% published both asymptomatic and symptomatic data.

Hannah Lu and her colleagues used student enrollment as a proxy for population when calculating incidence across 30 colleges. This estimate was imprecise: the number of students was consistently lower than student enrollment, and student enrollment excluded the other people coming to campus, such as faculty, staff, and daycare participants. We expect that in most but not all situations, student enrollment overestimated the true on-campus population, in turn underestimating the true incidence.

As more campuses return to in-person classes, understanding the true size of the on-campus population is crucial. To understand COVID-19 testing and cases in their temporal setting, we need the concurrent on-campus population.

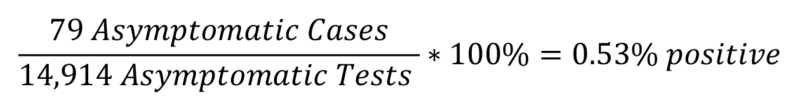

Second, some universities reported results only for asymptomatic tests. But an accurate measure of a campus’s true positive test rate requires results from both asymptomatic and symptomatic tests. The positive test rate tells us about the performance of the university’s testing program and provides important context for interpreting the number of total cases and incidence. Together, positive test rate and incidence indicate the current level of community transmission and whether enough testing is being done to catch these infections.

To illustrate the consequences of relying on asymptomatic data alone, we use the example of University of California, Berkeley, which provided both asymptomatic and symptomatic testing data. Using Berkeley’s asymptomatic testing data for a given week, we calculated the positive test rate:

However, when including the symptomatic testing data, we calculated:

Including only asymptomatic tests leads to underestimating the true number of coronavirus cases.

Although more than 85% of the sampled universities reported both test and case data, just 17 (around 25%)of these universities were reporting the data needed to calculate their true positive test rate, with data on both symptomatic and asymptomatic tests and cases. Twenty-three universities only reported asymptomatic data on either testing or cases, and another 15 were reporting undefined data where it was unclear whether the data included asymptomatic testing, symptomatic testing, or both (see Figure 1).

We expect that in most but not all situations, student enrollment overestimated the true on-campus population, in turn underestimating the true incidence.

In his study of a coronavirus outbreak at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Jeffrey E. Harris noted discrepancies between the university’s public dashboard and the Wisconsin Department of Health’s data on these same students. He suggested that the latter might include more off-campus student cases.

However, in their comparison of 30 universities (of which 20 were AAU members), Lu and her collaborators used such publicly posted university dashboards for their total case counts. Because at least two of these universities only reported asymptomatic test results and another four were undefined, these case numbers were likely underestimated. As a result, their calculated incidence, reproduction rates, and positive test rates were probably also underestimated.

Third, most universities did not report how measures evolve over time, instead opting to only show cumulative measures since the start of the pandemic. Time series data is important for understanding the situation as it evolves. It allows us to calculate the contemporaneous incidence and positive test rates needed to inform reopening strategies and mitigation measures. Without time series data on incidence, positive test rates, and mitigation measures, we also cannot causally infer how a new policy or the vaccine rollout may have influenced coronavirus incidence and positive test rates on campus and in the community.

Of the 17 universities in our sample reporting the true positive test rate, only 6 reported these metrics over time. Similarly, only 11 of the 15 universities reporting an undefined positive test rate did so over time. This means that at best, 27% of the sampled universities clearly reported a true positive test rate over time; conservatively, only 9% did.

Likewise, of the eight universities reporting the approximate campus population, none reported their approximate campus population metric over time.

Developing a standard

Eighteen months into the pandemic, scientists continue to work to understand COVID-19’s spread, including in vaccinated populations. Vaccine data, combined with data on symptomatic and asymptomatic testing and cases, are needed to understand not only breakthrough cases but also spread by vaccinated individuals. Because this silent spread could impact particularly vulnerable populations, including children and people with immune issues, this phenomenon is especially important to understand. Being able to monitor the behavior of COVID-19 is also key to preparing for a future in which we are likely to experience other global viral outbreaks.

Time series data is important for understanding the situation as it evolves.

Universities have a responsibility to their students and faculty, to the local communities they are embedded within, and to society as a whole. However, even in our survey of leading research universities across the country, none reported all of the data needed to calculate incidence and positive test rate over time.

Without a standard format for how universities report their coronavirus data, most have created their own customized dashboards, leading to inconsistent levels of data completeness and transparency. To gain a complete picture of incidence—and thus the impact of mitigation strategies—we recommend that university associations, such as AAU, the National Collegiate Athletic Association, and the American Council on Education, bring together the resources necessary to reactivate and expand the reach of We Rate COVID Dashboards or an equivalent and develop a dashboard standard. The chosen system should focus on the standards we propose, including time series data on asymptomatic and symptomatic testing and the true on-site population (resident and weekly visitors). Finally, the university associations should advocate for this standard by creating incentives, such as certifications that can be prominently displayed by universities.

The Delta variant is a harbinger of many unknowns for the future of this virus, making it all the more important that universities continue testing both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals and improve upon their communication of those data. By conducting and reporting time series data on symptomatic and asymptomatic testing and the true on-campus population, universities will better fulfill both their social responsibility to the community and their scientific commitment to rigor, quality, and transparency. In addition, by taking the actions we propose, universities will set a standard for other institutions to strive to achieve.