Tracing the Roots of Motion Capture

Modern motion capture technology owes a conceptual debt to the early twentieth-century innovations of Frank (1868–1924) and Lillian Gilbreth (1878–1972), whose pioneering motion studies laid the groundwork for today’s sophisticated systems used in biomechanics, animation, and virtual environments.

Lillian Gilbreth, a psychologist and industrial engineer, and her husband Frank, an efficiency-focused engineer, collaborated with the goal of optimizing human labor. Their guiding principle, that there is “one best way” to perform any task, was rooted in the belief that reducing wasted effort could minimize fatigue, yielding both economic and personal benefits. Their work merged psychology, engineering, and design in ways that would prove prescient for future developments in motion analysis.

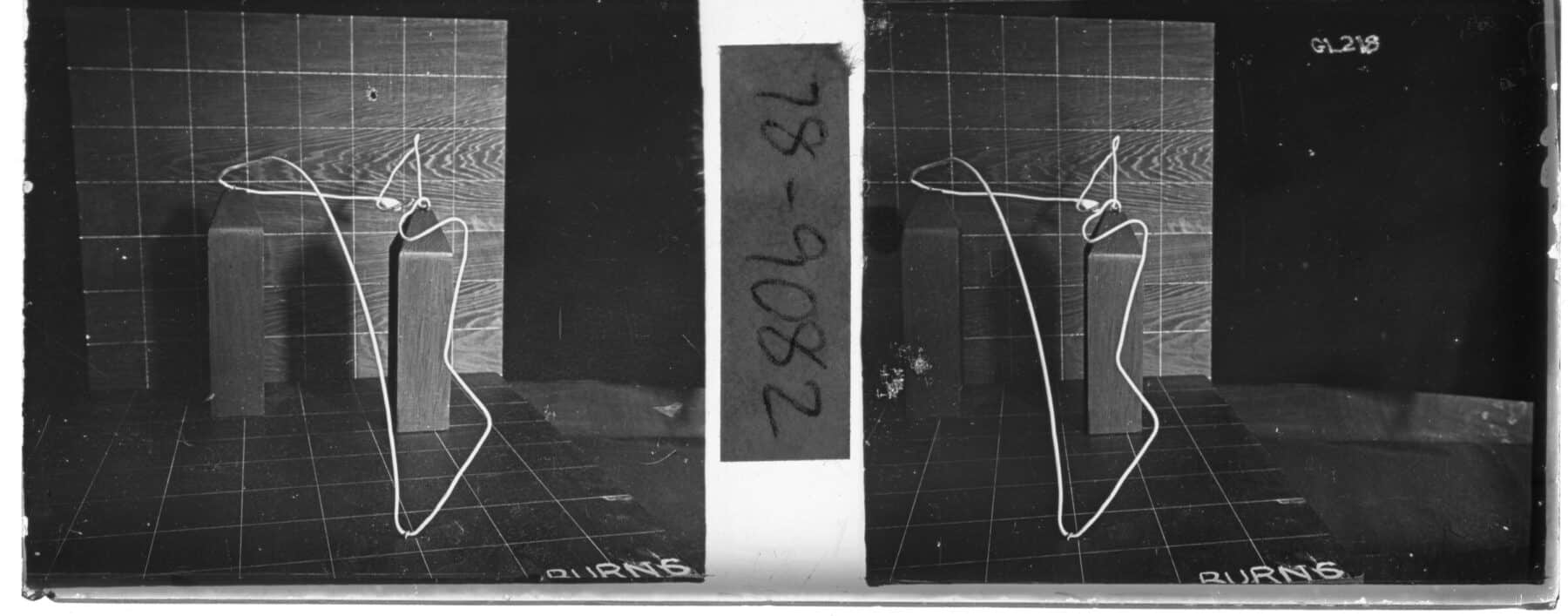

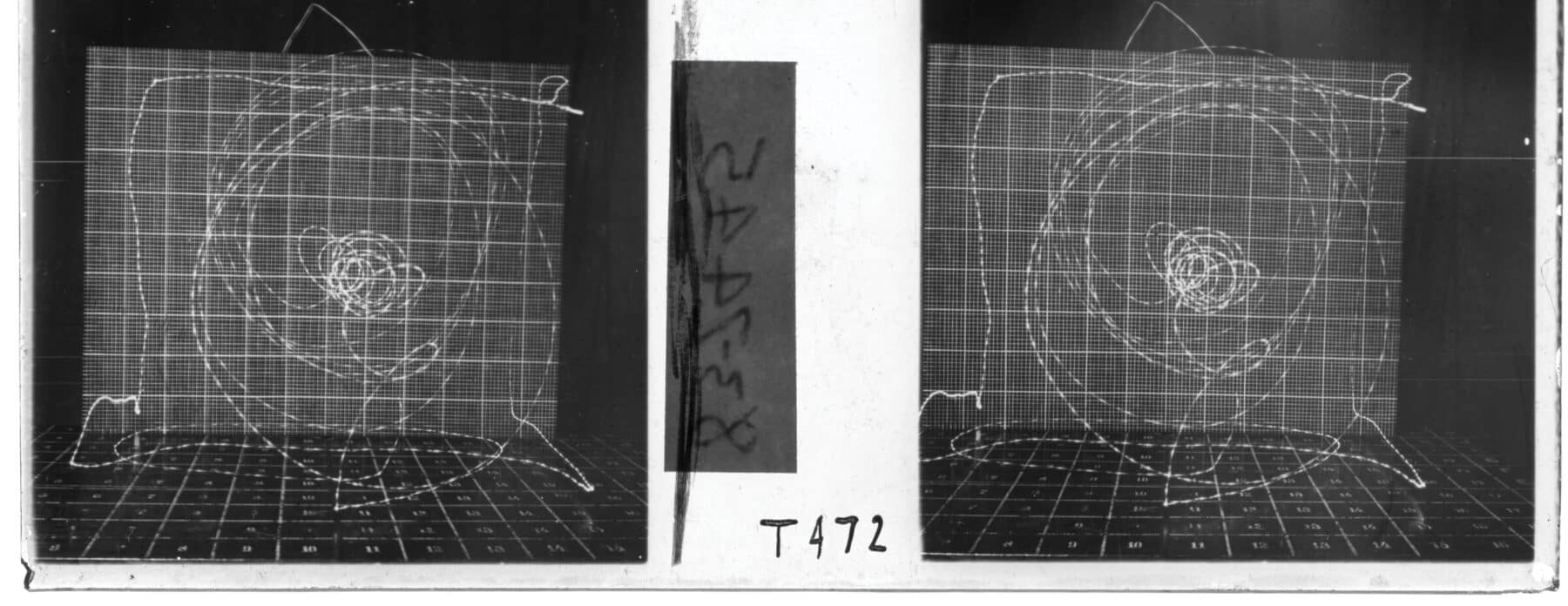

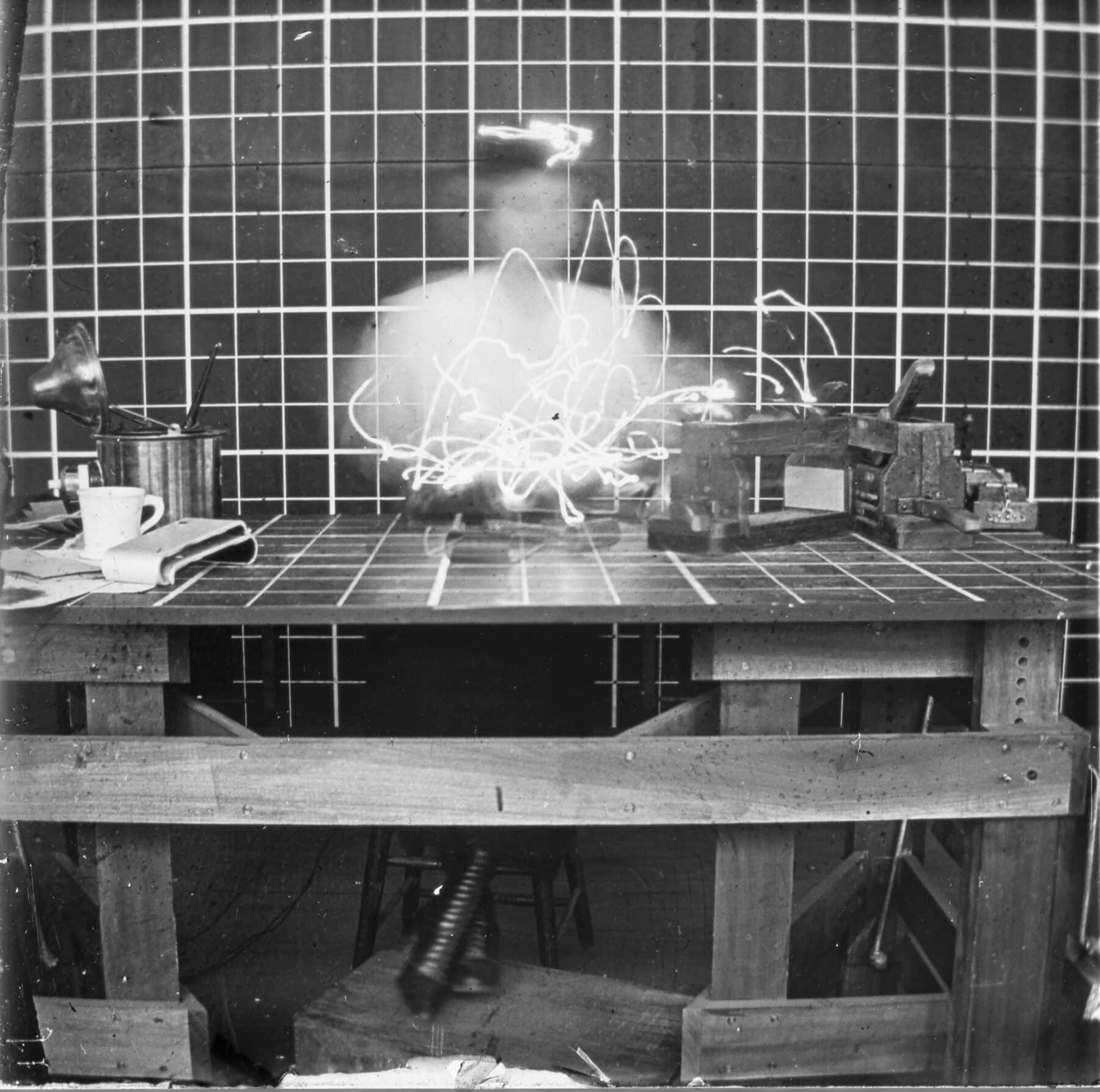

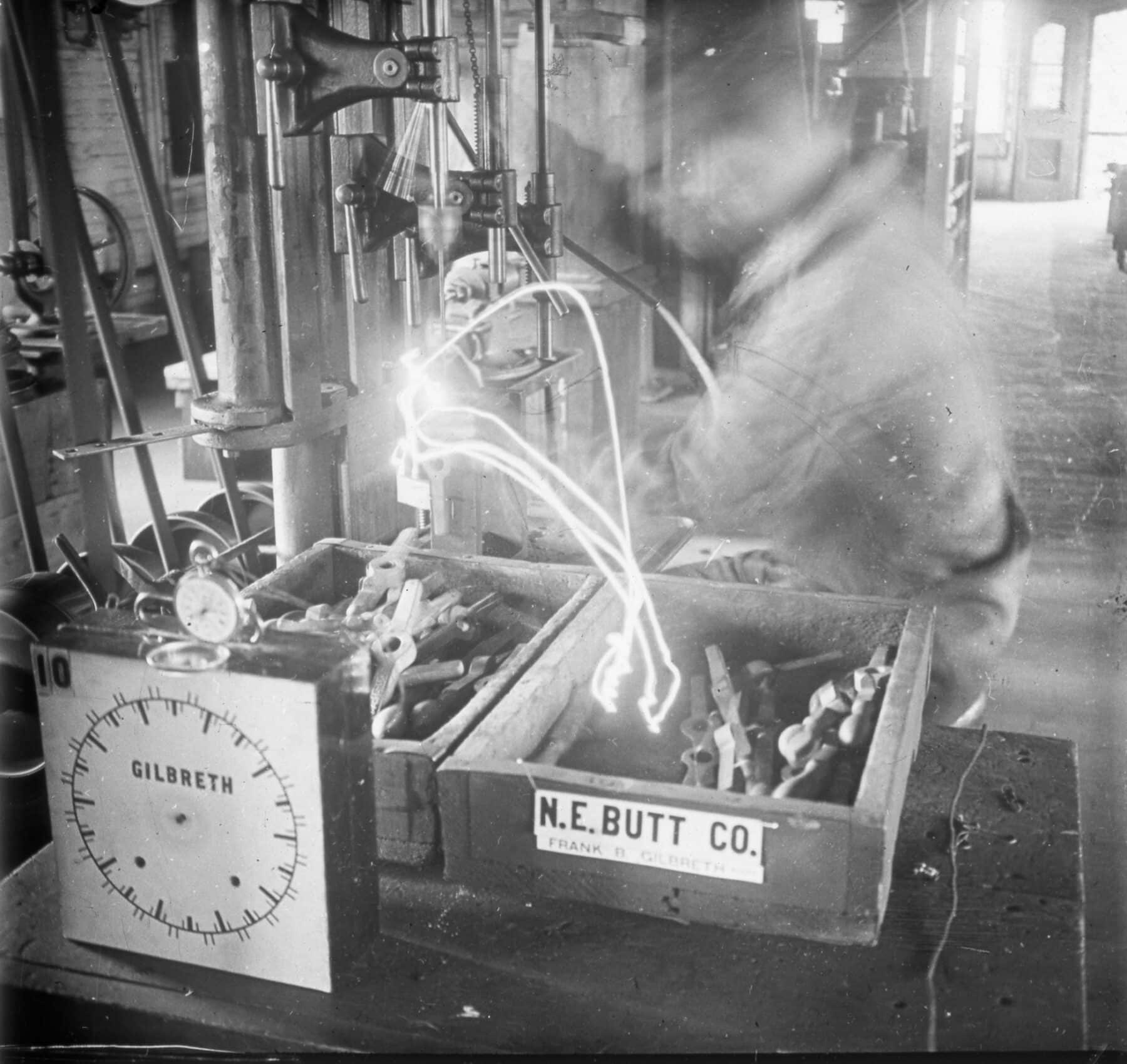

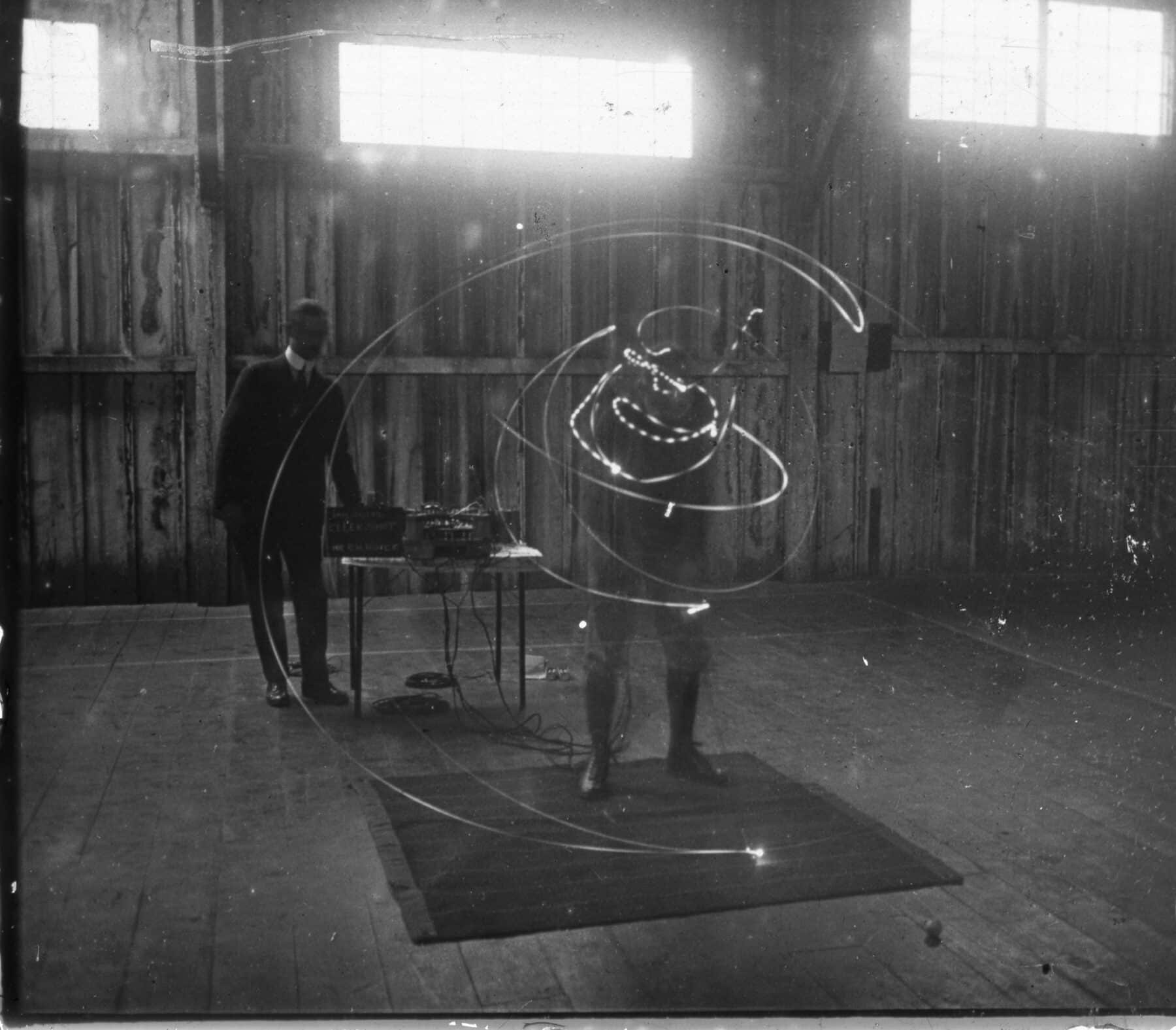

At the heart of their method was the cyclegraph, a system combining time-lapse photography with light-tracing techniques. Small lamps affixed to workers’ fingers captured the paths of motion as they performed tasks, creating luminous trails that mapped movement with striking clarity. These traces, which they sometimes transformed into wire sculptures, turned abstract gestures into physical models of efficiency. The Gilbreths’ findings informed improvements in surgical training, military drills, assembly line design, and hospital workflows by isolating and eliminating unnecessary motions.

After Frank’s death in 1924, Lillian continued their work of researching, writing, teaching, and consulting for businesses and manufacturers. Facing gender discrimination in engineering, she turned her focus to domestic efficiency, despite her personal dislike of housework and reliance on full-time housekeepers. Her designs were instrumental in shaping the modern kitchen, creating efficient layouts still in use today. The Gilbreth household itself functioned as a living laboratory, with their twelve children often participating in experiments. (Two of them coauthored the semi-autobiographical book Cheaper by the Dozen [1948], which later inspired several films.)

In 1965, Lillian became the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering—recognition of a lifetime advancing the science of human efficiency. The Gilbreths’ efforts to break down human motion into analyzable components foreshadowed the principles behind contemporary motion capture. Today, infrared cameras, reflective markers, and inertial sensors are used to generate real-time, high-resolution 3D representations of human movement. These digital reconstructions are now integral to fields ranging from ergonomic design to character animation and immersive virtual environments.

The evolution from cyclegraphs and light trails to digital motion capture systems reflect a century-long advancement in our capacity to observe, record, and understand human movement. Recognizing this lineage not only deepens our appreciation of current tools but also underscores the enduring goal in motion analysis: to reveal the structure of human effort and improve the ways we live and work.

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, Cyclegraph of male drill press operator at New England Butt Co. Motion clocks visible.

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, Cyclegraph of golf swing. Man with cyclegraph equipment visible in the background.