HIBAR Research: The Frontier Is Actually an Ecosystem

Thinking about technological advance as the result of interactions in an ecosystem rather than as a linear process will greatly accelerate the innovations that contribute to the public good.

The recently proposed Endless Frontier Act (S.3832) seeks to revitalize America’s global leadership in technological innovation. The act correctly recognizes that the nation’s capability in science, technology, and innovation is a tremendous resource, one that is spread across many institutions spanning academia, government, and the private sector. But it fails to move decisively past a flawed linear model of innovation—one embodied in policy yet outmoded and unequal to the challenges facing the nation. It is time to revisit some basic assumptions to help pave the path forward.

The current linear model—which holds that innovation starts with basic research, is followed by applied research and development, and ends with production and diffusion—derives from Science, the Endless Frontier, the famous report by Vannevar Bush, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s World War II science advisor. It recommended that after the war, government-funded university research should be freed from considerations of use, so scientists could focus on purely curiosity-based investigations. Society was to rely mainly on the private sector for practical research. The idea created separation instead of collaboration between “ivory towers” and the “real world.”

Research that serves the public good but is unlikely to generate profit is generally not funded by the private sector and is left to the public sector to fund.

Overall, this separation of curiosity-based and practical research was not an immediate problem for the national innovation system because long-term basic and applied research thrived together in the corporate laboratories of AT&T, Xerox, IBM, GE, 3M, Honeywell, and many others. This kind of research, stimulated by the strong interaction of basic investigations with anticipated public benefits (and, accordingly, good profits), produced many important breakthroughs. They were recognized in commercial success and numerous Nobel prizes. Many researchers who have been part of this type of research know what it felt like. It felt good!

Over time, though, increased competition forced industrial focus to shift to nearer-term interests, limiting the funds and research cycles available for deep, long-term corporate research. The venture capital industry intensified this private sector shortening of time horizons over the past 25 years. Instead of truly addressing longer-term societal needs, private investors are now more likely to back innovators that are growing quickly and then exiting through IPOs or acquisitions.

Even when the linear innovation model produces potentially critical innovations such as cancer drugs, the excessive profit motive built into the final commercialization stages can reduce positive societal outcomes. Research that serves the public good but is unlikely to generate profit is generally not funded by the private sector and is left to the public sector to fund.

Simultaneously, the academic incentive system has devolved to focus more on publication metrics than fundamental advances. This leads to wasted research effort that prioritizes instrumental individual academic career gains above improving society through discovery. There is a clear need for significant adjustment, and now is the perfect time.

Instead of rearranging innovation policies to reinforce a disproven linear model of innovation, the Endless Frontier Act can and should take a different approach. Using proven methods, it can solve the present collective action failure in which university, government, and industry researchers are too often misled by divergent incentives.

Major breakthroughs are more likely when researchers collaborate across institutional, sectoral, and disciplinary boundaries, instead of merely hoping that any work they choose to pursue will be equally likely to make disciplinary advances and help solve significant problems.

This will require some adjustment, because the proposed act currently overemphasizes the technological frontier, without considering the more complex embedded nature of the underlying technological and societal problems. It would organize research around specific technological focus areas, such as artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and biotechnology, with universities positioned as the principal sources of fundamental knowledge for making progress. But major breakthroughs are more likely when researchers collaborate across institutional, sectoral, and disciplinary boundaries, instead of merely hoping that any work they choose to pursue will be equally likely to make disciplinary advances and help solve significant problems. Society’s innovation ecosystem sectors should be mutually reinforcing, making their whole greater than the sum of their parts.

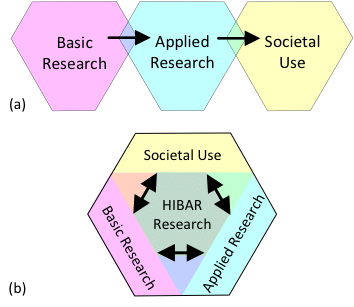

A truly responsive research ecosystem should value, encourage, and reward deep, trans-sectoral research partnerships that are simultaneously basic and responsive to societal challenges. These partnerships must go beyond awareness and friendship—they require co-partnership and indeed co-leadership of collaborative research. In our work over recent years, our growing network of colleagues has converged around a label for this historically generative form of research: HIBAR, an acronym for Highly Integrative Basic and Responsive. HIBAR projects span multiple sectors and institutions, combining fundamental discoveries with their practical and effective application. Projects excel through the intense, passionate, shared leadership of academic and nonacademic visionary experts, who urgently guide basic research toward solving long-term societal problems. HIBAR research is focused around solving problems, not advancing disciplinary agendas, although disciplinary breakthroughs are often stimulated by the work. Figure 1 compares the linear model for innovation with the more realistic and improved HIBAR model.

Figure 1. A comparison of (a) the outmoded unidirectional linear model for innovation with (b) a more realistic ecosystem model that yields faster and better innovation through shared leadership and the recursive multilateral flow of ideas. HIBAR research lies at the nexus.

Importantly, this is not at all a new idea—it’s a time-honored one. HIBAR projects have been responsible for far more than their fair share of the great research advances of humankind. They have improved health, reduced poverty, and defended nations, as shown in dozens of studies and recently detailed in two books: Cycles of Invention and Discovery and The New ABCs of Research. Indeed, the major corporate laboratories of the twentieth century likely succeeded because critical HIBAR feedback loops between different types of research and different sectors, in the context of problem solving, were integrated into their structure and mission. Past HIBAR research led to breakthroughs such as the transistor, cell phones, the Global Positioning System, and the internet, and today they underpin the Endless Frontier Act’s 10 proposed focus areas. But that is history. Looking forward, although it isn’t possible to confidently predict the details of tomorrow’s breakthroughs, very likely most will arise from future HIBAR research, so society should strive to do more of it, not less.

Fortunately, this would not be a radical new role for government-supported research. Numerous government agencies and laboratories, which are mission-oriented by their very nature, have long combined long-term basic research with applied efforts in the same agency or in the industrial supply chain. Excellent HIBAR exemplars exist within the domains of national security (Department of Defense), energy (Department of Energy), agriculture (Department of Agriculture), and space (NASA). Already, many university researchers work directly with those programs, creating HIBAR linkages and bolstering combined progress in basic and responsive research. The Endless Frontier Act can and must build upon this superb base.

Although it isn’t possible to confidently predict the details of tomorrow’s breakthroughs, very likely most will arise from future HIBAR research, so society should strive to do more of it, not less.

Predictions of the most important future research areas are often quite inaccurate. But a steadfast truth has been that HIBAR research produces amazing unanticipated benefits, in addition to those being directly sought. For example, the inventors of the transistor were addressing the challenge of producing reliable amplification for long-distance telephone lines, which they solved, and in doing so they also fueled nascent investigations in solid state physics and data science that have since revolutionized human existence.

Yet nine of the Endless Frontier Act’s 10 proposed focus areas are research domains not directly linked to societal-level problems that desperately need solutions. The exception is “natural or anthropogenic disaster prevention.”

This approach would reinforce the worrisome overall decrease in society-wide HIBAR research in recent decades, which could have been avoided by compensatory increases at universities. Unfortunately, so far that has been discouraged by academic incentive systems focused on short-term publication metrics, which undervalue societally beneficial innovation. This is a critical systemic collective action failure that society must now address. Everyone would benefit from better using society’s innovation capabilities, and in turn that requires important, practical changes in the current research ecosystem. Currently, by our estimate, only about 5% of university research projects are HIBAR—but this is a good base upon which to build, with sound policy. Boosting the HIBAR fraction of overall research would provide opportunities for researchers in both fundamental and applied fields to undertake projects with a greater potential for societal benefit, which will also generate breakthroughs within their own research fields.

Although increased funding for HIBAR research would be a good start, there is also a need for cultural and structural change in order to most effectively deploy such resources. Just as HIBAR projects require diverse shared leadership, the transformation of the National Science Foundation into a new National Science and Technology Foundation (NSTF), as proposed in the legislation, should embrace partnered leadership with expertise in research and in the application of research and technology to societal problems. This applies at both the program and top leadership levels. Instead of operating in silos, leaders with multiple perspectives would head major initiatives together as collaborators. That “dual hat” leadership can instill an agency focus that collectively appreciates and understands the multiple benefits of HIBAR research. This shared leadership would enact the required structures and procedures for strengthening the HIBAR research culture within the greater innovation ecosystem.

Today, NSF has a unique opportunity to transform and lead. With the introduction of the Endless Frontiers Act and its expanded NSTF, we see a major opportunity to lead the transformation of innovation that connects the rapid advance of fundamental science to the solution of urgent societal problems.

So, what changes are specifically needed in the Endless Frontier Act to seize this leadership opportunity?

NSTF structure. The missions and structures of the new NSTF should be deeply interdependent. NSTF should embody shared leadership that integrates across science and technology domains to ensure the integrative design and benefits of HIBAR research. The act proposes using the label “Technology Directorate” for the administrative unit within NSTF responsible for advancing the technology focus areas identified in the bill, but that could imply that technology is a separate, stand-alone field, akin to a pit stop along the current one-way linear path of innovation. There are numerous ways to avoid this problematic symbolism, and a critical one would be shared collaborative leadership that deeply understands and values HIBAR research.

We see a major opportunity to lead the transformation of innovation that connects the rapid advance of fundamental science to the solution of urgent societal problems.

Advisory. The proposed Board of Advisors for NSTF needs to be built with a deep and broad vision. It should incorporate multiple views about societal problems and research opportunities, to help guide the research mission underpinning the entire agency. Leaders operating at the HIBAR forefront in academic and nonacademic settings would be able to provide deep, future-focused insights arising from their world-class, visionary projects. But the board must also include people with deep experience and understanding of the societal problems that NSTF research aims to solve.

Funding structure. Programs should cross institutional, sectoral, disciplinary, and topical boundaries instead of being narrowly siloed. Instead of a focus primarily on types of research, there should be equal attention to the various types of societal problems those areas of research can address. Therefore, the 10 proposed focus domain areas should be revisited to appropriately include the societal challenges that the legislation aims to address.

Funding procedures. Funding decisions for HIBAR research projects are a more complex challenge than for standard NSF grants because they have diverse leadership and participants who are employed in universities, companies, government agencies, and nongovernmental organizations. Appropriately improved project selection, contracting and operating procedures could include multi-staged funding models that encourage initial inter-sectoral discussions, which eventually lead to full HIBAR research programs, which would also encourage shared leadership. Naturally, funding decisions must include the judgment of experts with experience in initiating, funding, and conducting HIBAR research. Funding should be prioritized for well-defined research projects that simultaneously comprise the essential HIBAR characteristics of (1) seeking new knowledge (excellent basic research), (2) seeking societal solutions (excellent applied research), (3) excellent trans-sectoral co-leadership, and (4) a profound sense of urgency combined with the endurance required to solve major problems.

HIBAR research is well aligned with the stated goals of the Endless Frontier Act, and can help achieve them. Because an essential goal of HIBAR research is to contribute to the public good, governmental action is needed to ensure the collective efforts required to greatly accelerate this type of research. Designing the Endless Frontier Act from a HIBAR perspective, instead of the unrealistic linear model of basic research separated from technology and innovation, will help solve the collective action problems and market failures of the current innovation ecosystem.