Technoscientific Bodies

Fritz Kahn’s early-twentieth-century conceptual illustrations spoke to a world transformed both inside and out.

At the dawn of the twentieth century the future arrived as a cascade of technologies, arranged and rearranged in ever more powerful configurations—the telephone, x-ray, anesthesia, elevator, electric light, electric fan, skyscraper, typewriter, motion picture, phonograph, wireless telegraphy (soon renamed radio), automobile, airplane, and the industrial city. New inventions, sounds, sights, styles—new ways of living. Proliferating, accelerating, enchanting modernity.

That escalating, intensifying change received extravagant representation in newspapers, magazines, posters, and billboards. To please readers who increasingly demanded novelty and action, a new genre of illustration was invented—the modernist conceptual scientific illustration—which combined halftone photographs, words, visual metaphors, and technological diagrams. And in the 1920s, Fritz Kahn (1888–1968), a German-Jewish physician and popular science writer, became its first great exponent. The images he created, in collaboration with a congeries of brilliant, imaginative commercial artists, surprised and delighted people around the world, who loved seeing themselves and their times represented in Kahn’s technoscientific bodies.

The new genre was inspired by an American prototype. In Chicago in 1917, Winfield Scott Hall, a professor of physiology at Northwestern University, prepared an illustrated article, “What Strange Land is This? The Bodies We Live In,” for Pictured Knowledge, a multivolume encyclopedia sold by salespeople door-to-door. Tucked between articles by other leading Progressive Era thinkers, Hall explained the workings of the human body through metaphors of a modern well-administered city or nation.

But the illustrations for Hall’s article took a different tack, using industrial machines and processes to create a picture of the modern self. The head (“headquarters”) is rendered as a suite of offices featuring switchboards connected by thickets of wires through which senses are received, decisions made, the body operated. Beneath the headquarters, the body is a factory, though not terribly complex—a simple agricultural combine and food processing plant. The innovation is that anatomical parts and physical processes are transformed into modern machines and technologies. The body is an industrial site.

A few years later, in central Europe in 1921, Hanns Günther edited an illustrated essay collection on the human body, Wunder in Uns (The Miracle in Us). For his introductory essay, Günther had an artist redraw Hall’s illustrations.

In Berlin, Fritz Kahn took notice. With his stable of artists, Kahn was already producing a stream of profusely illustrated books and articles on medicine and biology. But his encounter with the strange new illustrations utterly transformed his approach.

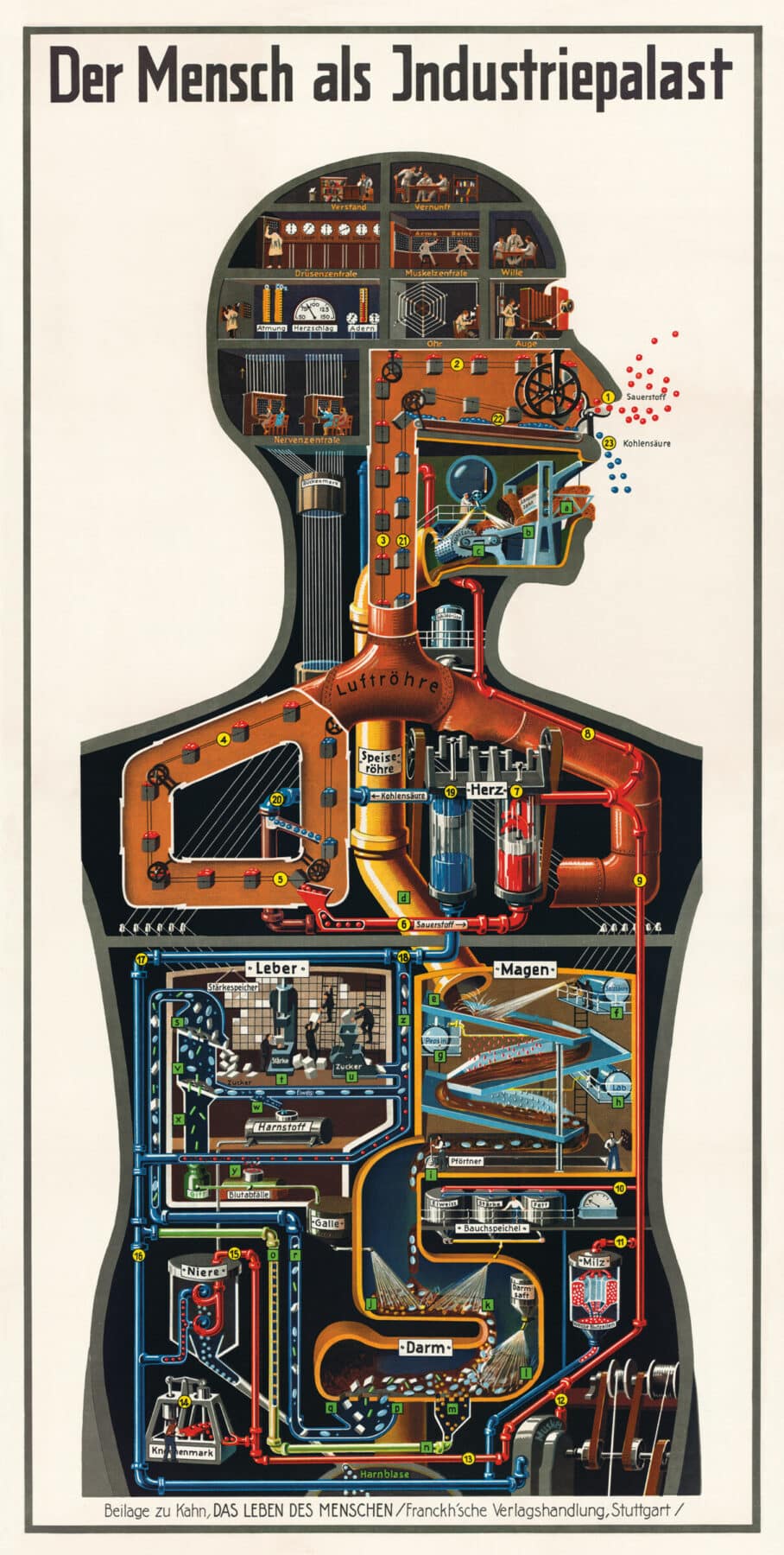

He began by borrowing and developing the cutaway cross-section body-factory concept for a series of illustrations, most notably the 1926 four-color, life-size poster, “Der Mensch als Industriepalast” (“Man as Industrial Palace”). Designed with a distinctively modernist aesthetic by the (uncredited) artist Fritz Schüler, “Der Mensch” depicts the human body as a modern chemical plant to visually explain the chemistry and mechanics of respiration, digestion, sensory transmission and processing, and even the intellectual activities of the brain. Dynamic, complex, and sequential, the image is a human flowchart, with the body divided into boxes, like a comic strip. Yet in one way, “Der Mensch” is static: the armless, legless body doesn’t much interact with the outside environment, has no agency. Its only function is to operate itself.

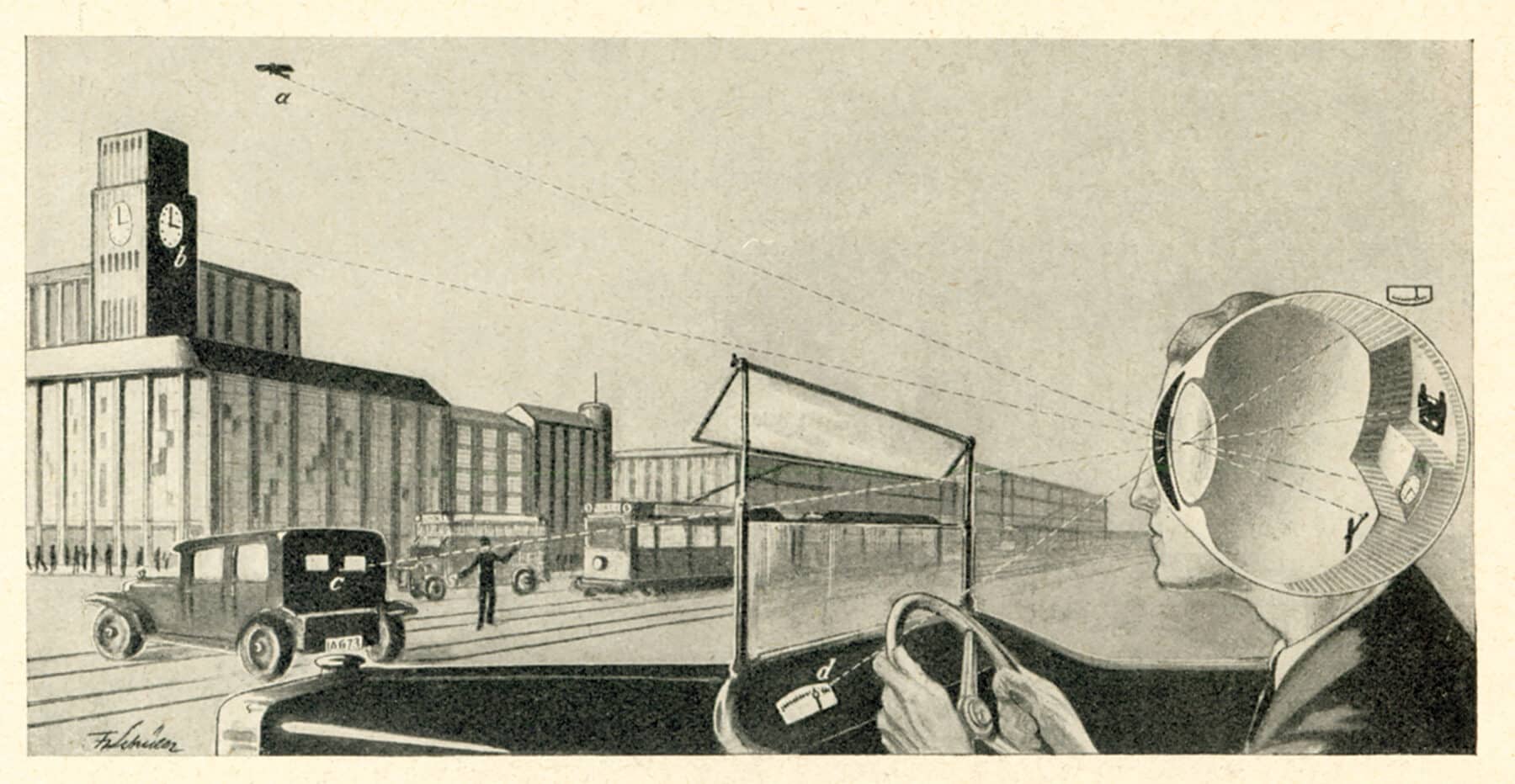

Through the 1920s and ’30s, in thousands of illustrations, Kahn and his artists developed more dynamic and aesthetically modernist approaches to visual explanation. The human body interacts with the industrial environment, mass media, crowded modern cities, skyscrapers, electric lights, automobiles, speeding trains—and these elements also appear inside the body. The illustrations are complex visual metaphors that situate the body in industrial modernity and put industrial modernity inside the body.

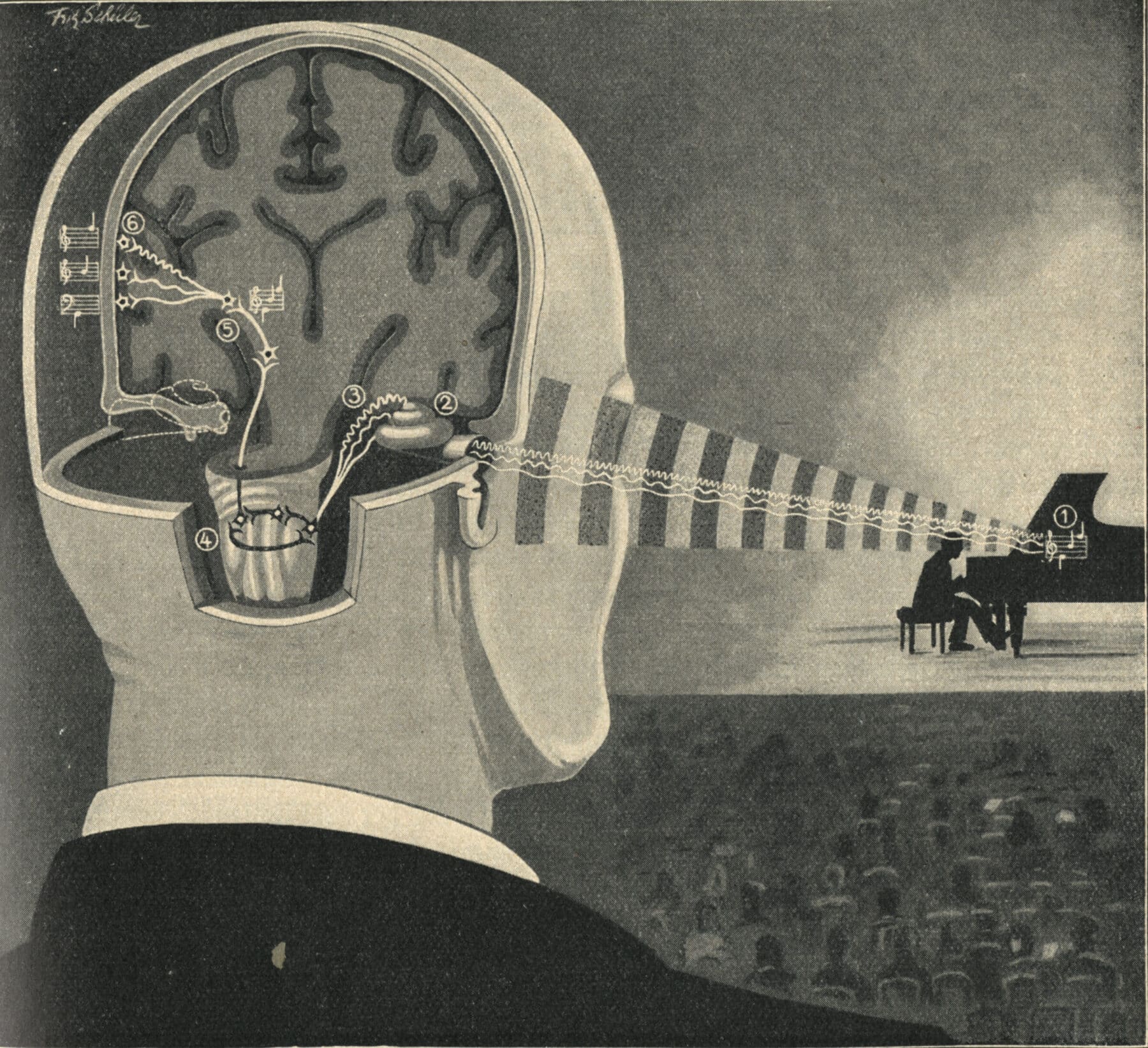

Kahn’s most talented artists—Roman Rechn, Alwin Freund-Beliani, Otmar Trester, Arthur Schmitson, Fritz Schüler—excelled in presenting that fusion of built technological environment and humanity. They were particularly inspired by the task of visually explaining the physiology and physics of the senses: hearing, touch, taste, smell, and especially the optics of vision and the eye, which became the emblem of the dizzying milieu of industrial life and its new immersive audiovisual devices and culture.

Kahn’s most talented artists excelled in presenting that fusion of built technological environment and humanity.

Some of those illustrations not only depict cognitive effects; they also aim to induce them. Viewers see themselves in the image, observing themselves as observational machines; there is a mirror effect. Other illustrations bring into the mix a kind of estrangement by displaying what cannot be seen: sound waves and x-rays, transmissions that proceed through the city, the air, and the body.

Ultimately, Kahn and his artists fell under their own spell: their pleasure in putting on a show entirely overtook the educational aims of popular science. Their lessons are often contrived, just a pretext to playfully perform the transformative experience of modernity, inside and outside the self, strange and familiar, disorienting, surreal, fun, and utopian.

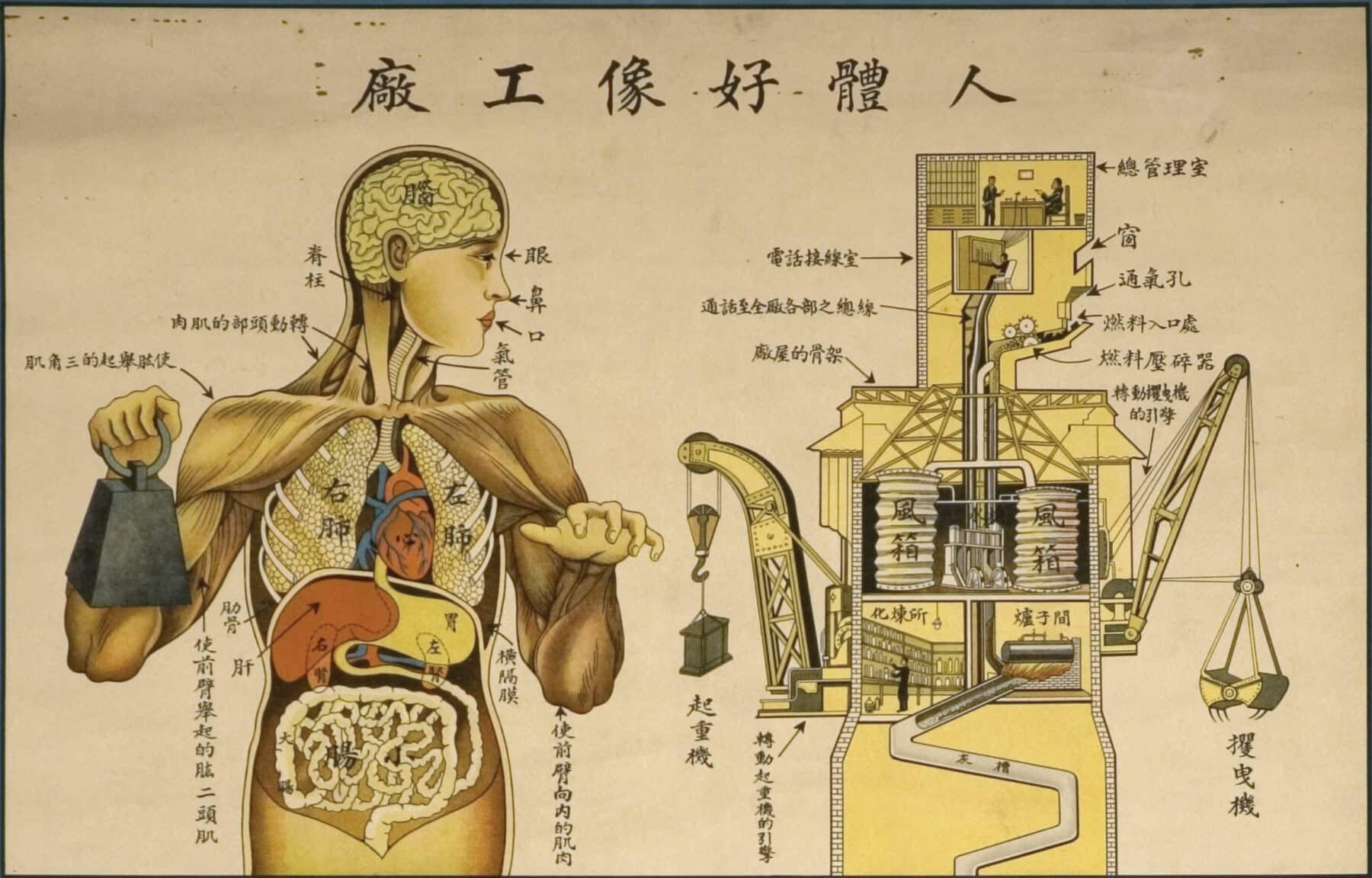

When Hitler rose to power, Kahn’s books were banned, but his illustrations reappeared, uncredited, in health and popular science publications by “Aryan” authors. Forced into exile—first Palestine, then Paris, then (after the fall of France) New York—Kahn continued writing books and articles, published in the United States, Switzerland, Brazil, and other countries, recycling his old illustrations (in new versions, reworked by new artists), with plenty of new illustrations added. And around the world—in Europe and North America, but also China, Latin America, the Middle East, and the Soviet Union—artists, authors, publishers, public health organizations, exhibition designers, and curators took the new approach and ran with it.

By 1940, the world was at war, and Kahn’s representational fusion of humanity and technology took on new force and new meanings. The iconography of invisible physical forces—electricity, sound waves, radio waves, light rays, x-rays, pressure waves, radioactivity, heartbeats, brainwaves—pervaded the cultural landscape, appearing in popular science publications, daily newspapers and monthly magazines, science fiction pulps, animated cartoons, horror movies, public health posters, and advertising. In the modern world of great cities linked by global mass media, the merger of humanity and its technologies and the paradoxical synthesis of escalating human agency and helpless objectification seemed ever more like a fact of nature, at times horrific and—in Kahn’s images—often delightful.