The Subversive Beauty of Fallen Fruit

Halfway through Agnès Varda’s film The Gleaners and I (2000), a judge in full regalia stands in a field of newly harvested tomatoes and reads an edict from 1554 that authorizes “the poor, the wretched, and the underprivileged to go to the fields after the harvest, from sunrise to sundown, and glean leftover fruit and vegetables.”

The artists David Allen Burns and Austin Young of Fallen Fruit have joyfully adopted the ancient practice of gleaning and brought it to contemporary urban neighborhoods. “We invite you to experience your city as a fruitful place,” they write, “to radically shift public participation and the function of urban spaces, and to explore the meaning of community through creating and sharing new and abundant resources—like fruit trees.”

David Allen Burns and Austin Young of Fallen Fruit have joyfully adopted the ancient practice of gleaning and brought it to contemporary urban neighborhoods.

Fallen Fruit began in 2004 when Burns, Young, and Matias Viegener, who left the collaboration in 2013, created a map of their Los Angeles neighborhood showing fruit on the margins of public space that could be harvested. Through their ongoing project Endless Orchard, Fallen Fruit continue to map urban fruit trees, organize community fruit tree plantings, and talk about public spaces as shared resources. Their many years of working with fruit has taught them that fruit is not only sweet—it has a long cultural and political history. Planting a grove of fruit trees can be a radical act and a gesture of hope.

In Monument to Sharing, a recent public artwork near the Ann Street entrance of Los Angeles State Historic Park, Burns and Young planted a grove of 150 orange trees, including 32 in large, galvanized planters. Each planter is labeled with a phrase from a neighbor in the surrounding community. Together the phrases become a poem of their collective voices, wrapping around the public orange grove.

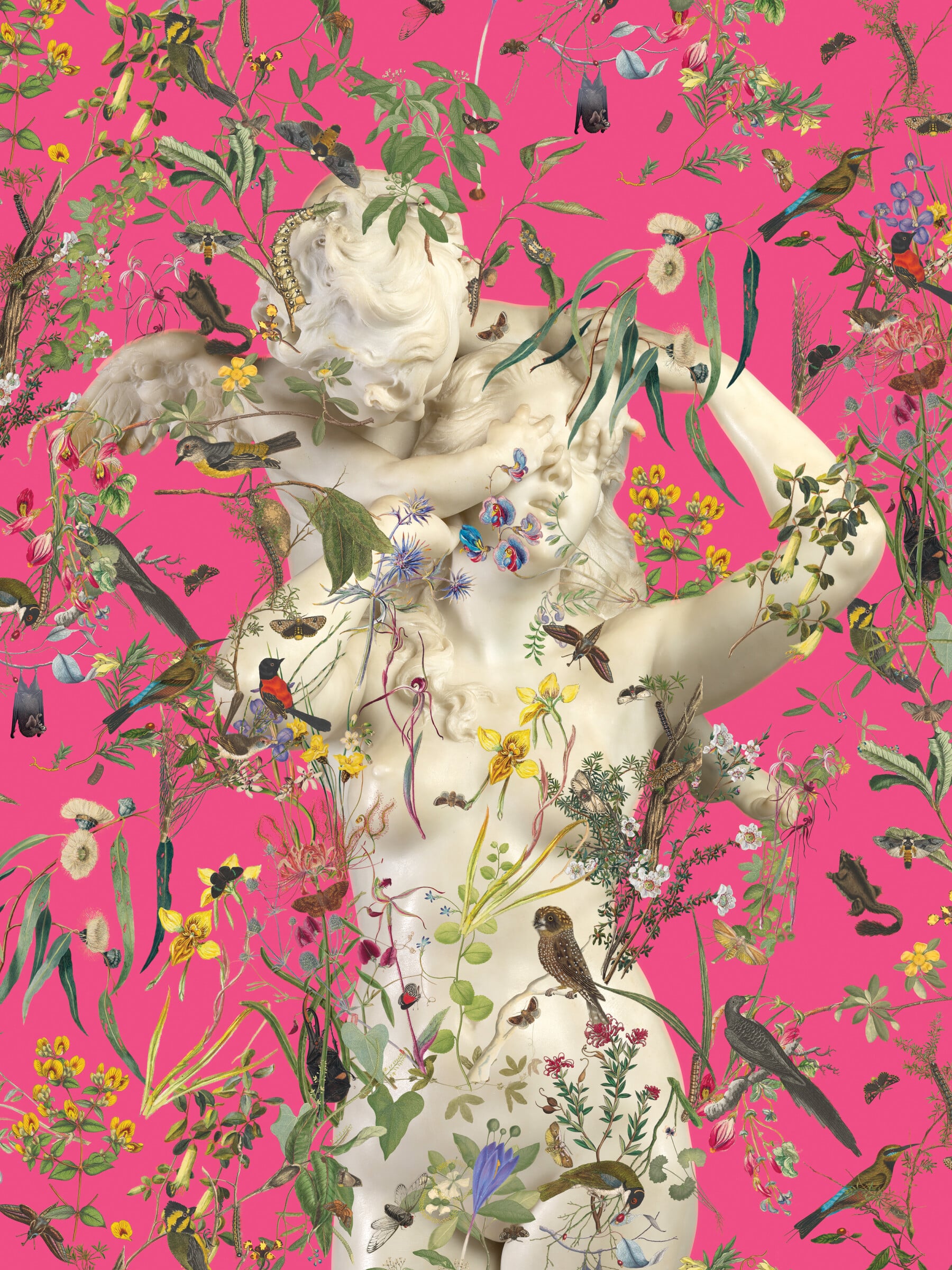

Since their first museum installation in 2010, Fallen Fruit have been invited to art museums and cultural institutions around the world. Their immersive installations assemble a portrait of each institution; they reframe historical collections with exuberant and sumptuous wall coverings, which then form a canvas for the atypical placement of carefully chosen historical objects from the museum’s collection. They add to this by creating neighborhood fruit maps, which link the installation to the world outside the museum’s walls.

They reframe historical collections with exuberant and sumptuous wall coverings, which then form a canvas for the atypical placement of carefully chosen historical objects from the museum’s collection.

The artists are unabashed maximalists who love color and invoking the senses, but once they seduce with beauty, they invite viewers down paths that consider issues of colonialism and the natural world, class, race, gender, and religion. In 2019, Fallen Fruit delved into the archives at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London to create an asynchronous repeat pattern wallpaper for the exhibition FOOD: Bigger than the Plate. When the artists learned that from 1681 until the museum was built in 1857 the land where the V&A now stands was the site of a famous nursery, they used fruit-laden wallpaper to bring back the spirit of that history.

Other collaborations have taken a darker turn, as in Promised Land at the Genia Schreiber University Art Gallery at Tel Aviv University in Israel. The artists designed a wallpaper that combines images representing the historical movement of plants in North Africa and West Asia with current issues around the precipitous decline of birds of prey in the region.

By gleaning the historical collections of art museums, the artists reveal the subversive power of turning the museum inside out.

—Text by Shirley Alexandra Watts. All images courtesy of David Allan Burns and Austin Young.