A Brief Note From the Guy on the Table

A traumatic brain injury gave me a crash course in a medical research system tangled in technological dilemma and political paradox, a dysfunctional insurance bureaucracy, and the wondrous healing powers of superglue.

I’d wanted to have a scan of my brain since 1975, when I first learned about computerized tomography (CT) as a medical student in anatomy class. But it wasn’t until April 2023, just a few weeks before I turned 70, that I actually saw the seat of my soul and source of my livelihood. It was an unhappy occasion.

For several weeks, I had been bumping into things on my left side, getting increasingly frustrated with my keyboard for all the typos flowing from my left pinkie and ring finger, and eventually experiencing left-sided weakness and unstable balance. It took me 10 minutes to put on my pants in the morning. I fell down at a conference in Washington. And given my lack of coordination, I probably should not have taken that chain saw safety class that entailed cutting through a log.

So, accompanied by my wife and daughter, I took a trip to Georgetown University Hospital’s emergency room, where the ER doc suspected I’d had a stroke. This provisional diagnosis was extremely distressing, as a stroke implied cell death caused by blocked blood flow or bleeding directly into the brain, which could leave permanent damage. Five hours into my visit, I was wheeled into the CT scan room, and then back to the ER, where we reviewed the results on a tiny screen.

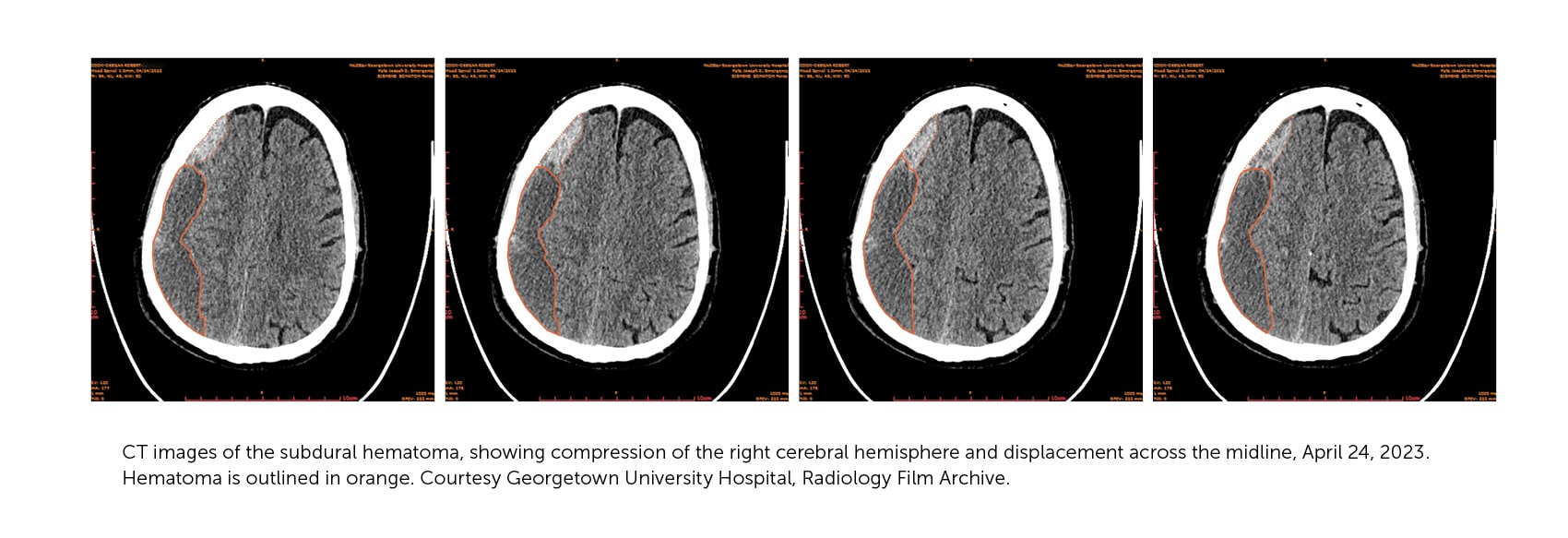

Even at low resolution, the CT image explained a lot. Instead of a stroke, it showed a possibly reversible injury: a chronic subdural hematoma. It was what I had suspected. On the screen, we could see the pool of blood accumulating and mushing my brain across the cranial midline. A blood clot inside your noggin is not a good thing. It takes up precious real estate in a confined space housing a squishy organ. The blood was positioned over the right sensory and motor cortex, causing the weakness and poor coordination of my left side.

I was relieved that the stroke diagnosis was mistaken, but it was just one in a series of glitches in my effort to get treatment for my symptoms. As a physician who has worked in science and health policy for five decades, I have studied the myriad ways that policy fails to meet the challenges of making health care effective, affordable, and accessible. But abstract studies are starkly different from being the guy on the operating room table. I got a crash course in the irony of so-called health insurance; a research system tangled by technological dilemma and political paradox; and the wondrous healing powers of superglue and expert care.

Early the next morning after the CT scan, a team of interventional radiologists threaded a catheter into my right wrist, up through my radial artery, navigating through the brachial, common carotid, external carotid, and internal maxillary arteries to finally reach the middle meningeal artery, where they injected cyanoacrylate (superglue) to embolize (plug up) the artery that fed the leaky, traumatized membrane that had been oozing blood for three months. Just wow.

I have studied the myriad ways that policy fails to meet the challenges of making health care effective, affordable, and accessible. But abstract studies are starkly different from being the guy on the operating room table.

The hematoma was the relic of incomplete healing. Earlier that year, I had fallen while skiing with my daughter and soon-to-be son-in-law. I never lost consciousness and apparently was coherent, or at least as coherent as usual, recounting details about Dopesick to them on the chairlift just minutes after the fall. I was wearing a helmet, but perhaps not a good one. I still have no memory of the fall or anything else for about an hour after the fall (anterograde amnesia due to brain trauma, for those in the business). I developed a nasty black eye and my memory was shaky for few days. But I seemed to revert to normal and, unwisely, resumed skiing after a couple days—this time with a fancy new helmet. Luckily, I didn’t fall again. More ominous symptoms only began to appear two months later, and then slowly intensified. This timeline is not unusual in old folks who bump their heads.

After the radiology team plugged up the artery that fed the subdural hematoma, a neurosurgery resident drilled a hole through my cranium, screwed on a pipe that was hooked to a tube with a suction bulb at the end—a subdural evacuation portal system (SEPS in the literature). About half a cup, or 121 mL, of blood was sucked out of my cranium over several hours, although they left the unit on for a few days.

Back in the neurological intensive care unit after the surgery, I scared the nurse by dancing a little jig with my wife—SEPS unit still sticking out of my head. I was already feeling normal again. If only my mother had still been around to enjoy this: One of her favorite expressions was “I need that like a hole in the head,” and we would have laughed that I really did need one. Another CT scan the following morning showed just a thin layer of residual blood, and a month later, even that was gone. All told, I had a very happy ending, as evidenced by the fact that I’m now writing this essay. My biggest lasting symptoms are recurring thoughts of what I learned throughout my ordeal about our health care system.

What is urgent, anyway?

The first thing I learned is that the system has two speeds: urgent and wait-and-see, with little middle ground. I only went to the emergency room because my daughter and wife intervened, knowing I wouldn’t go on my own. I was aware something was wrong and that it should get evaluated; I just didn’t think it was all that urgent. Neither did the health care system.

As symptoms became apparent in mid-April, I asked a neurologist acquaintance what he thought. He referred me to the head of neurology at Johns Hopkins, who said my symptoms merited follow-up by brain imaging and forwarded my email to a resident, but the earliest appointment for new neurology patients was in July. I was put on the waiting list.

A call to our primary care doctor led to an examination and a prescription for imaging, which was requested through United Healthcare, our insurer. The primary care team scheduled a CT scan for April 29. But when my symptoms worsened on April 25, my wife and daughter called the primary care team, and they insisted I go quickly to the emergency room.

It’s a good thing they did, because unbeknownst to us, my insurer—or actually eviCore, the contractor to which United Healthcare outsourced it—sent a letter requesting more information on April 25, the day I went to the ER. Three letters arrived at our home after I returned from the hospital, ironically following two surgeries, three CT scans, and four days in the intensive care unit. Only by going directly to the emergency room was I able to get my symptoms confirmed and the necessary care. That said, insurance did cover most costs, including the imaging and surgeries.

Newly reinvigorated by my surgery, I bundled the three letters and wrote a tart note to eviCore pointing out that I did not plan to supply the requested additional information since I had just returned from having a 2.1 cm subdural hematoma drained, discovered by the very imaging test they had failed to approve initially despite the recommendation of the primary care doctors and findings of a physical therapist.

So far, this story highlights some well-known flaws of the US health care system: a fragile referral network, an overwhelmed neurology unit, and an insurer that outsources preauthorization requests to a contractor who communicates through the US Postal Service.

Superglue on the brain

But there is another element of my experience that deserves attention: How did the system come to use superglue to fix my brain? Who in the world would do such a thing? At a rehabilitation clinic a week after leaving the hospital, while reviewing a postsurgical CT scan (the fourth one), the rehab doc commented, “A lot of times with this, you just go to sleep one night and never wake up.” Now that I was out of the ER and pretty much back to normal, we could feel relieved and joke about it. But commonly cited statistics on subdural hematomas (SDHs) are scary: Nearly half of patients are dead or severely disabled within three months. The condition is relatively common and, as the population ages, it’s slated to become even more so—with some experts projecting that SDHs will be the most common cranial neurosurgical condition by 2030.

One saving grace was that my brain had shrunk with age, leaving a bit more room inside my cranium for blood to accumulate. It turns out this odd accommodation often comes with age. You don’t just grow in wisdom. Wisdom accretes in a shrinking brain mass, which turns out not to be such a bad thing if your brain needs to share space with several months’ worth of oozing blood. But that smaller brain also increases the risk of blood vessels tearing when jostled, and not healing properly, so the risk of chronic subdural hematoma rises with age.

How did the system come to use superglue to fix my brain? Who in the world would do such a thing?

Another contributing factor to my survival was our going to an excellent, high-volume hospital with expertise in detecting and draining chronic subdural hematomas. After returning home, I scoured the scientific literature, highly motivated to see what research had been done on my kind of SDH, caused by slowly oozing rather than gushing blood. I pulled about thirty papers. The embolization method, also known as middle meningeal artery embolization, or MMAE, was pioneered in Japan in 1994, then picked up in Europe and North America, where most of the papers originated.

The procedure has been used for at least 15 years in the United States and Europe, but I did not find a randomized, controlled trial comparing which embolization material is optimal, which method of draining the blood is best, or what order to do the procedures. Most reported trials were small, or were sponsored by the makers of an embolization material and tested only one. Many trials, including a recent troika published in the New England Journal of Medicine (two in November 2024 and one in February 2025) and another study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (July 2025) were either observational trials with historical controls, or compared embolization to “standard treatment”—draining the hematoma without plugging the middle meningeal artery. Yet at the hospital where I turned up, embolization is now effectively routine.

The medical literature reports embolization as a “recently emerging procedure,” 30 years into its development and use. Randomized trials are finally beginning to report out, and consensus panels are starting to set some tentative clinical guidance. But these clinical reports all call for more research to establish an evidence-based standard of care. So after three decades, the evidence needed for a robust practice guideline is still missing for a common and growing clinical condition. Cases like mine are one reason. I had a great outcome, but the data won’t be able to inform future care because follow-up stopped at one month and I was not part of any formal study. My data are wasted.

The weak evidence base is not because there aren’t enough patients. Estimates suggest there will be roughly 60,000 chronic subdural hematoma patients each year in the United States by 2030, presumably most often covered by Medicare, given the demographics. Veterans Affairs must also cover many such patients, though I was unable to find current numbers from either Medicare or the VA on the number or type of procedures. In any case, it would be good for the federal government to know the most effective way to deal with SDHs, since federally funded health programs are paying for the lion’s share of clinical care. Why doesn’t it?

Technological dilemmas and political paradoxes

Part of the problem is that when SDH treatments are studied, it’s only a few patients at a time at one or a few sites. Randomization is hard. Only half the patients asked to join one newly reported medRxiv study did so. I myself might have refused to join a trial that entailed randomization as to whether I’d receive embolization, if I’d reviewed the literature. Who wants to get randomized to yesterday’s less effective procedure, especially when the risks are so dire? Meta-analysis is possible, but amalgamating small observational studies can be misleading. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) started a large, 33-site trial comparing embolization to surgery that should run to 2029. Perhaps that will produce stronger clinical guidance. Yet it will depend on sites meeting their recruitment targets and NIH having a budget to cover the trial, neither of which is a safe assumption given the threat of grant terminations, budget cuts, and the fact that embolization is now widespread, so randomization seems suboptimal to prospective patients.

In hindsight, looking at the size of the need, it’s evident that a multicenter clinical trial needed to be done shortly after the procedure was first imported from Japan, not two decades later. Failure to finish a large-enough randomized, multicenter clinical trial now would be penny-wise and pound-foolish, but that’s where we find ourselves. In the meantime, this is a typical example of how the health care system fails to capture the information it needs to lay the foundation of evidence for future care.

Forty-five years ago, the scholar David Collingridge identified this dilemma for technical systems: It is far easier to deflect the trajectory of a new technology soon after launch than when it is in full flight, but the information needed to assess impacts awaits widespread adoption. That is, it is easiest to intervene in how a technology is being used early, when information is sparse, and hard to fix once its widespread adoption makes its impact apparent. Medical technology is no exception. We spend a lot of money on health research that could provide the requisite information—if only it were organized. Success in this case would have meant collecting information over the past three decades about how chronic subdural hematoma was managed by many centers and what happened to the patients.

It is easiest to intervene in how a technology is being used early, when information is sparse, and hard to fix once its widespread adoption makes its impact apparent. Medical technology is no exception.

Leaving funding for trials largely to device manufacturers doesn’t produce the sort of insights into comparative effectiveness and safety that are necessary to guide clinical treatment. A few of the hospital-funded or publicly funded trials do test different treatment modalities, but systematic evidence is needed to optimize practice. Medicare could get better answers by using “coverage with evidence development” as a tool, but that has been used rarely and has not worked out well in practice. One reason is that Medicare’s formal statutory authority to do research to generate evidence informing coverage and reimbursement has been questioned. And even if it was clear, the links among the payer, Medicare, and the agencies with best expertise to design and carry out clinical studies are notoriously weak. Medicare writes checks, but has never grown a brain.

Why health care lacks a brain

Some lessons about our health care establishment emerge from this story. My hospital has apparently adopted a very promising high-tech way to manage an increasingly common health problem in the Medicare population. It costs a lot. Doctors are not completely sure what optimum care looks like yet. Insurers, for their part, have tried to limit costs through demonstrably flawed preauthorization measures. My wife’s wry response to the eviCore letter we got after we came home from the hospital: “I guess they wanted a note from the morgue.”

This conundrum will not be solved by a “market.” Given that the federal government is the main payer, it seems the perfect spot for a government-funded research organization to step in. But the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—the agency whose mission most closely aligns with the need for evidence about effective health care—generally focuses on bigger-ticket items. That is, when Congress and the president are not trying to kill it. AHRQ is the successor to the National Center for Health Services Research and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, both of which were terminated in 1989, and the National Center for Health Care Technology, which met its demise in 1981. The various names betray a hazardous political rollercoaster ride. Some agencies were killed; others have sought refuge in name changes and mission-tweaking to avoid elimination. The current AHRQ has itself faced several near-death experiences.

When the most valuable information an agency produces is what does not work, the companies, institutions, and people providing those goods and services do not welcome the news. They become a hostile constituency; hospitals, doctors, and health advocates are potent political actors. They can try to kill the messenger rather than abide by the message. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is somewhat immune from the direct threat of annual appropriations because it is partly funded through Obamacare, and its mission does indeed include research to improve clinical care. And the independently funded Institute for Clinical and Economic Review carries out health technology assessments but has limited bandwidth, and often finds itself battling providers. A twist on the Collingridge Dilemma that health analyst Richard Rettig once framed as “political suicide” unavoidably haunts health technology: Information that can improve effectiveness and efficiency for payers and the overall system will be vulnerable to highly motivated providers whose income is threatened.

Even though the federal government spends trillions of dollars each year on health services, with Medicare and Medicaid expenditures alone exceeding $2 trillion in 2024, it lacks an analytical framework to guide prudent purchasing.

And so we are left with today’s impasse: Even though the federal government spends trillions of dollars each year on health services, with Medicare and Medicaid expenditures alone exceeding $2 trillion in 2024, it lacks an analytical framework to guide prudent purchasing. The government should be spending billions strategically to make its trillions more effective, building an evidence base that private payers could use to guide decisions on their even-larger slice of the pie. This better system is technically feasible but politically perilous. Without an agency with the mandate or the staying power to examine what health care works best, the US health care system’s brain works even worse than mine did with an SDH.

The human touch

Threading a catheter through a maze of arteries to inject superglue in my brain was truly amazing, a tribute to high-tech medicine. Just as incredible was the human touch—all the teamwork, attentive care, and emotional support provided within the context of a vast hospital bureaucracy and its beeping machines. The ER was a mess, but that’s because it was crowded, hectic, and—well, an ER. No worse, and indeed better, than many I experienced in my medical training. But in this environment, the interventional radiologists were focused and supremely competent as they answered my questions and coordinated with the separate neurosurgical team. I was slotted into the operating room just hours after the fateful CT scan results, and the two teams that did both operations (embolization and drainage) rotated so I did not have to move between operating rooms for different services. The handoff to rehabilitation and follow-up was excellent. That was good planning that prioritized the patient’s needs, and it took institutional resources to make it happen.

But most important to my experience was the superb nursing care I received once I got to the neurological intensive care unit. I am deeply grateful to the nurses who helped me through one of life’s nadirs. I returned almost two years later to Georgetown’s new and beautiful neurological intensive care unit and brought a copy of my book for those who had taken care of me. They were still there, and two of them were on duty. I’m not sure anyone will want to read about the origins of the human genome project while on break on the unit, but it seemed like the most personal thing I could do to express my gratitude.

When I think of that awful time, I always return to the phenomenal care I got. It’s proof that the flaws in the system are not so much due to any lack of caring, but rather the stupid way we have organized the system—bad policy. We’ve managed to master crazily complex methods of caring for our fragile, squishy brains, but we still need to mobilize our institutions to fix the policies that guide paying for and evaluating that care. If we can inject superglue into an artery with exquisite accuracy, surely we can apply a fraction of that ingenuity to fix these other macro problems.