Faith & Science

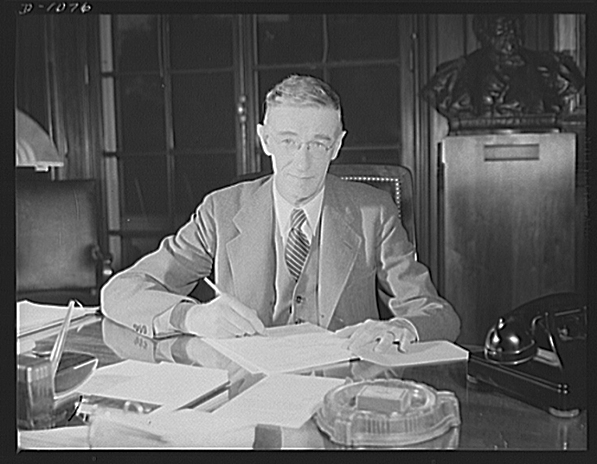

A half-century since his death, Vannevar Bush is best known for his formative role in the rise of computing and for conceiving of, and helping birth, the National Science Foundation, the leading supporter in the United States of basic scientific and technological research. During his life, Bush (1890–1974) was better known as the organizer of the Manhattan Project and as a science and military technology adviser, first to President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II and then to Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry Truman, immediately following the war.

To this day, Bush’s Science, the Endless Frontier shapes thinking about science and society and the government funding of research. But much of his finest writing remains unknown, unavailable, and unappreciated. It is worth our attention because—even though he invariably referred only to men in his writing—Bush profoundly influenced how all of us think and write about the technological foundations of the everyday human-built world.

Bush was also deeply involved in scientific debates that still resonate today. The historian of science Thomas Kuhn, in his 1962 book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, created controversy by comparing the belief systems of scientists with religious belief systems. Explanatory frameworks in natural science, Kuhn argued, could function as a reigning orthodoxy, with a prevailing “paradigm” rejecting or ignoring contrary evidence—with a near religious fervor—until the evidence becomes so compelling that a new paradigm, or belief system, replaces the old one. Though he appears never to have engaged Kuhn directly, Bush anticipates some of the ideas in Kuhn’s book in this excerpt from his 1955 letter to employees and supporters of the Carnegie Institution of Washington that science and research depend on a kind of belief that resembles religious or spiritual faith. “For the scientist lives by faith,” he writes, “quite as much as the man of deep religious conviction.”

—G. Pascal Zachary

As we regard the present material progress of man and his probable future, we can see that he is headed for catastrophe unless he mends his ways and takes thought for the morrow. This is quite apart from the immediate question whether he will use the split atom or a trained virus to turn civilization back and force it to begin again its slow upward climb—apart from the question whether great wars can be avoided through a general understanding of their consequences. These are momentous questions, but they are immediate ones, and so they must be resolved by other patterns of thought than those of long-range fundamental science, which—though it may profoundly influence the fate of future generations—can affect the present course of events only rarely. They are questions in which all scientists are deeply interested, but primarily as citizens and members of the community—questions to which they can contribute only as citizens or as their background in science enables them to counsel wisely with those who apply science and those who apply other disciplines, all of whom today find some pertinence of science to their problems.

Many a research program is conducted in which the researcher has no clear idea as to what he is trying to find out or what it would mean if he found it.

Wars aside, man is still headed for trouble … [so we might understand if] the sole motivation of fundamental science [is] to prepare the way for later useful applications and thus fend off … catastrophe. And do we always have [momentous goals] clearly in view? Of course not. A great deal of research is done as a matter of habit, because it is the fashion of the time or the practice of the community. We seldom stop to think of why we do what we do; in fact we seldom think philosophically at all. Many a research program is conducted in which the researcher has no clear idea as to what he is trying to find out or what it would mean if he found it. Men work for years without stopping to examine critically the relevance of their efforts. Curiosity is often the underlying motivation, and not a bad one. It was probably responsible for the discovery by Prometheus of how to make a fire. Emulation is often clearly present, especially when a great scientist is surrounded by disciples. The competitive spirit, fortunately now on a more friendly basis than in the past, has a strong part in scientific motivation. It has become less artificial and less acrimonious as caste distinctions and false pride have lost their hold and as the stuffed shirts among us have dwindled almost to extinction. And the sporting instinct, whatever that is which causes men to pit themselves against great odds, to revel in trial and adversity, to breathe the stimulating air of self-justification in success, no doubt is often present. We do what we do for many unavowed reasons, and seldom pause to analyze them. But when we do reflect, we find that our primary motivations in scientific effort extend far beyond our casual and momentary reasons, even beyond the thought that what we do may, in its small way, benefit the human race in its struggle to control its environment and itself in the grim days that are sure to come.

[The scientist’s] dependence on the principle of causality is an act of faith in a principle unproved and unprovable.

For the scientist lives by faith quite as much as the man of deep religious conviction. He operates on faith because he can operate in no other way. His dependence on the principle of causality is an act of faith in a principle unproved and unprovable. Yet he builds on it all his reasoning in regard to nature. This is even truer today than it was some 60 years ago when William James so forcibly reminded us of it. Some of us, confronted with the bizarre as we delve into the nucleus of the atom or try to pin down the elusive electron, wobble sometimes in our basic faith that natural events are determined by unique causes, that, from a physical standpoint, the present fully determines the future. We become confused as to whether, when we include ourselves as part of the system, causality is departed from. But we still proceed in our daily round on the assumption of unique cause and effect as the basis for all our experimentation. It is becoming apparent also that the acceptance of any system of logic for reasoning about our sensory experience is an act of faith, and that our reasoning appears sound to us only because we believe it is and because we have freed it from inconsistencies in its main structure—for [our reasoning] is built on premises which we accept without proof or the possibility of proof.