Rekindling the Slow Magic of Agricultural R&D

The economic evidence for increasing public investments in national and international agricultural R&D is overwhelmingly strong.

Much of the world’s attention over the past year has been focused—as it should be—on combating the COVID-19 pandemic. By some estimates, more than 1.7 million people worldwide died directly from the disease last year. And yet, a separate, more familiar threat killed even more people. At least 2 million children under the age of five died from hunger and related illnesses—a typical yearly toll. The deaths of additional millions of older children and adults are annually added to this dismal tally. And deaths measure only part of the harm done by severe lack of food and the “hidden hunger” of micronutrient deficiencies, which cause stunted growth, wasting, and greater vulnerability to infectious diseases and other preventable illness.

As staggering as these statistics are, they could have been much worse. Agricultural research conducted in the 1950s and 1960s led to the so-called Green Revolution of the 1970s and 1980s. Thanks in large measure to the development of higher-yielding varieties of wheat and rice, among other advances, agricultural R&D has since helped to save hundreds of millions of people from poverty and famine. Indeed, over the past several decades, economic studies show that R&D-driven improvements in farm productivity have helped drive down food costs and global poverty rates.

Deaths measure only part of the harm done by severe lack of food and the “hidden hunger” of micronutrient deficiencies, which cause stunted growth, wasting, and greater vulnerability to infectious diseases.

Unfortunately, funding for agricultural R&D has fallen in recent years and is under renewed threat given other pressing priorities for government budgets and the dire overall projections for economies recently outlined by the World Bank. But this is exactly the wrong time to decrease public investments in agricultural R&D. About 1.8 billion people (a quarter of the world’s population), primarily in Africa and South Asia, remain desperately poor—living on $3.20 or less per day. World Bank data show that the COVID-19 pandemic pushed an additional quarter of a billion individuals into this category in 2020.

Public investment in agricultural R&D has paid off handsomely in the past and will continue to do so—assuming governments provide the necessary resources. Nations should be increasing these investments, not just to sustain progress already made in the face of climate change and ever-tighter land and water supplies, but also to continue to shrink the number of people living at the lowest levels of poverty and increase resilience to major disruptions such as COVID-19. The totality of the available evidence supports at least doubling the total global public investment in agricultural R&D—currently about $40 billion per year or $5 per person.

The unfinished agenda

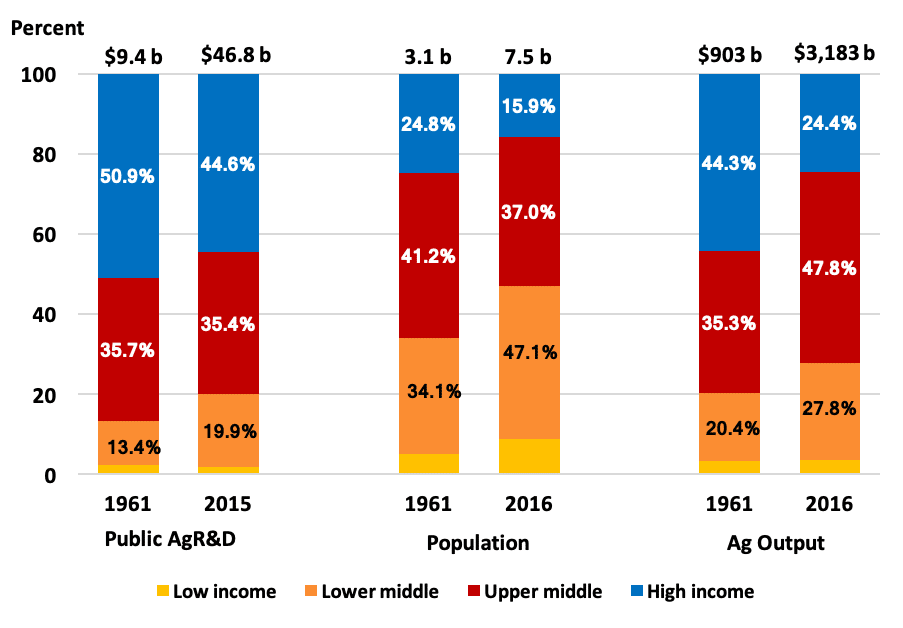

Much has changed over the past several decades with respect to agriculture and food production and the prevalence of poverty, hunger, and malnutrition around the world (see Figure 1). The balance of food production and public agricultural R&D spending has shifted from high-income countries toward the highly populous middle-income countries, especially China, Brazil, and India. In the lower-income countries output has not kept up with population. Today’s low- and lower-middle-income countries account for almost half of the world’s mouths to feed but produce only one-quarter of global agricultural output.

Figure 1: People, Production, and Public R&D for Agriculture, 1961–2016

Generally speaking, agricultural R&D targeted to poor people involves a mix of public and private efforts, conducted nation by nation, plus a purpose-built international system established in 1971 as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, now known simply as the CGIAR. Started with just four centers, the CGIAR today effectively operates with 13 internationally conceived and funded research centers.

Public investment in agricultural R&D has paid off handsomely in the past and will continue to do so—assuming governments provide the necessary resources.

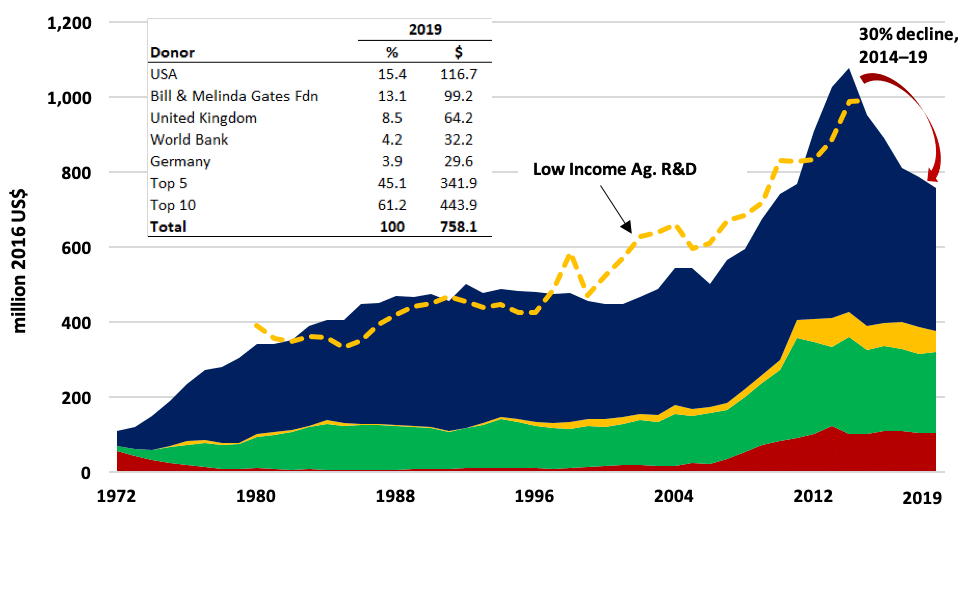

The CGIAR was conceived to play a critical role, working in concert with national agricultural research systems of low- and middle-income countries, to develop and distribute farm technologies to help stave off a global food crisis. The resulting Green Revolution technologies were adapted and adopted throughout the world, first and foremost in South Asia and parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America where the early centers of the CGIAR were located. In 2019 the CGIAR spent $805 million on agricultural R&D to serve the world’s poor, down by 30% (adjusted for inflation) from its peak of over $1 billion in 2014 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sources of Funding for the CGIAR 1972–2019

Today, the CGIAR continues its focus on enhancing global food and nutrition security, reducing hunger and poverty, and improving natural resource management. With a strong presence and long-term partnerships in developing countries, it is well positioned to develop agricultural innovations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of South Asia, where food shortages and poverty persist most stubbornly.

Some skeptics have expressed concerns about the ability of low-income countries, especially in Africa, to meet food security targets while also addressing the environmental agenda confronting agriculture. The CGIAR could potentially play a pivotal role in supporting that effort.

A 10:1 research payoff

The CGIAR research record has been much studied, but questions remain about the past and prospective payoffs to the investment. Similar questions have been raised about public investments in the agricultural research systems of various nations—particularly those of poor countries that receive substantial development aid from richer countries. To address those questions, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of more than 400 studies published since 1978 that looked at rates of return on agricultural research conducted by public agencies in low- and middle-income countries. Of that total, 78 studies reported rates of return for CGIAR-related research and 341 studies reported rates of return for non-CGIAR agricultural research. (Full details of the meta-analysis are online at supportagresearch.org.)

An important feature of our work was the decision to restate the reported rates of return cited in the studies as a standardized benefit-to-cost ratio, which puts the different estimates from the diverse studies on a more meaningful, comparable basis. Across 722 estimates, the median ratio of the estimated research benefits to the corresponding costs was approximately 10:1 for both the CGIAR (170 estimates) and national agricultural research systems of developing countries (522 estimates). In other words, $1 invested today yields, on average, a stream of benefits over future decades equivalent to $10 (in present value terms).

The value of CGIAR spending from 1971 to 2018 was equivalent to $64.8 billion (in 2018 dollars). A tenfold return implies a huge payoff to this research investment: cumulative benefits well in excess of $600 billion. A check against gains from the growth in agricultural productivity over the same time frame validates these inferences.

As a further check on these findings, we dug deeper into nine large-scale research evaluation projects pertaining to CGIAR research mostly done in partnership with national agencies. After projecting gains to 2020, we found that the benefits across these nine studies was in the range of $1.8 trillion (in 2016 dollars). Furthermore, we determined that about a quarter of the benefit could be attributable to the CGIAR alone. Notably, all these estimated benefits accrued in developing countries, home to the preponderance of the world’s food poor. And yet, rich donor countries also reap benefits by adopting technologies developed by CGIAR research—“doing well by doing good.” For example, the yield- and quality-enhancing traits bred into new wheat and rice varieties destined for developing countries are also incorporated into most varieties used by rich-country farmers.

Start making sense

Agricultural research is slow magic. Returns accrue over long periods—decades—and realizing the full potential from agricultural R&D requires far-sighted investments. It is also a cumulative endeavor, best done with steady and sustained investments. The accumulated evidence shows that, in agricultural R&D, persistence and patience are well rewarded.

Our new findings from the meta-analysis, that past investments have yielded tenfold returns, also indicate that national governments and development partners have persistently underinvested in agricultural R&D at home and abroad. No doubt, investments in other national and global public goods (such as education, infrastructure, and public health in developing countries) have also yielded very high returns, but comparable (and comparably strong and abundant) evidence is not available to support a claim that those other opportunities yielded benefit-cost ratios in the range of 10:1.

Estimated benefits accrued in developing countries, home to the preponderance of the world’s food poor. And yet, rich donor countries also reap benefits by adopting technologies developed by CGIAR research.

Internationally conceived R&D explicitly addresses high-potential gaps in agricultural research programs of national systems—often multinational or global public goods. The unique position of the CGIAR allows it to leverage and reinforce R&D capacity in middle- and high-income countries as well as low-income countries, mainly for the benefit of low-income countries. The national systems have comparative advantage both in upstream, more basic research and downstream adaptive and translational research. The CGIAR centers have comparative advantage in doing intermediate applied and adaptive research to develop broadly applicable agricultural technologies that address high-potential gaps in the research systems of individual countries. The resulting internationally conceived R&D outputs and services complement those produced in national systems, and the measures of payoffs to CGIAR R&D typically reflect the consequences of R&D conducted jointly with national agricultural research partners.

In addition, the ongoing (and arguably increasing) challenges to global food supplies and farmer livelihoods posed by weather, pests, political strife, poorly designed policy, and market risks argue strongly for investing in agricultural research as a way to increase international resilience and preparedness. The totality of the available evidence supports at least doubling public investment in agricultural R&D performed by both national and international agencies. The benefits to date have been many times larger than the investments that generated them. We see no evidence of declining returns: meta-analyses have consistently shown that more recent investments deliver returns comparable to agricultural R&D done decades ago. We see ample scope for generating comparably large future net benefits.

In spite of this evidence, recent trends and geopolitical patterns in research investment are troubling. Governments in high-income countries have scaled back their investments in agricultural R&D, both at home and through the CGIAR. (See Figures 1 and 2, especially the blue shaded area.) Similar shifts can be seen in the total amount and emphasis of donor funding for CGIAR research. Total spending has shrunk markedly in recent years. Meanwhile, a much smaller proportion is now devoted to enhancing farm productivity with a larger proportion earmarked for improving policy, saving biodiversity, protecting the environment, and strengthening national agricultural research systems. And although many middle-income countries have expanded their national capacity in agricultural research, they have not contributed proportionately to the CGIAR. Indeed, many agriculturally large middle-income countries have yet to contribute significantly to funding the CGIAR.

The totality of the available evidence supports at least doubling public investment in agricultural R&D performed by both national and international agencies.

Meanwhile, many low-income countries have not yet developed their own capacity to any significant scale. In particular, research investment in sub-Saharan Africa lags significantly, and the gap with other regions of the world has grown. Some African governments are losing ground in their efforts to apply science and technology to current and future agricultural challenges, including climate change. One-third of the region’s national agricultural research programs spent less in 2015 than in 2000, after adjusting for inflation. This is particularly worrisome given the outsized importance of agriculture for livelihoods in these countries.

These funding trends can have dire long-term consequences. They fly in the face of the evidence on research payoffs at home and abroad and the many challenges confronting the world food equation. To put it bluntly, the world’s disinvestment in agricultural R&D makes no sense whatsoever. Boosting investments in agricultural R&D is an economically sensible and environmentally sustainable way to make food more abundant, cheaper, more nutritious, and more accessible to the world’s poor. Why not do it?