Public Views of Science Issues

Who should control the human genes used in research? (a) George Bush, (b) Leon Kass, (c) corporate America, (d) Kofi Annan, (e) you? If you said (d) or (e) you are in tune with the views of the general public, according to a recent poll. If you guessed wrong, you may be in for more surprises. Science policy experts assume that they have a pretty good understanding of where the public stands on current science-related debates. But sometimes it makes sense to ask.

The Center for Science, Policy and Outcomes (CSPO), a Columbia University think tank based in Washington, D.C., commissioned a poll of a representative sample of 1,000 geographically dispersed U.S. residents over the age of 18. The poll focused on core questions such as who should control science and who benefits from science, but also included more specific questions about scientific research issues, especially in areas of medical research and biotechnology. The results of the poll are surprisingly diverse. About most issues there is no “public mind” but rather “demographic group minds.” The respondents do have opinions about science and technology (S&T) issues but those opinions are neither simple nor predictable.

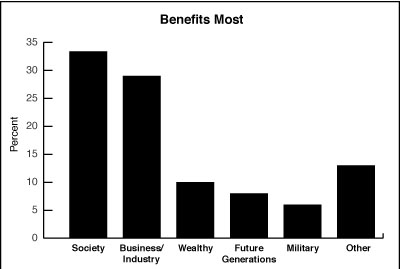

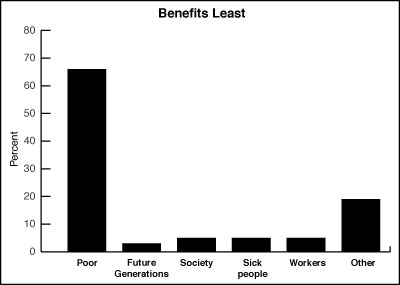

Who benefits most and least from the ways science and technology change the world?

The most striking result from this question is the broad consensus on who benefits least from S&T change. According to 70 percent of people with incomes less than $20,000, as well as 70 percent of those who earn more than $100,000, the poor benefit least. The idea that everyone gains from the S&T cornucopia seems to be an unsustainable myth. It is also a point that deserves more than passing notice from policymakers. When making research funding decisions, they might want to ask not only “for what?” but also “for whom?”

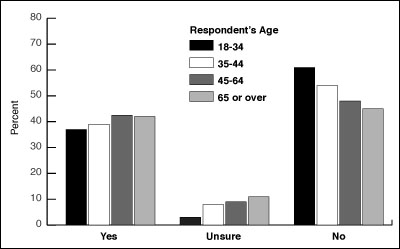

Would you be interested in slowing down or halting your own aging process, if the technology were to become available?

The first goal listed in Healthy People 2010, the National Institutes of Health’s strategic guidepost, is “to help individuals of all ages increase life expectancy and improve their quality of life.” Who could argue against slowing down the aging process? Apparently, most of us. Only 40.3 percent of those polled indicated that they would be interested. Even among those over 65, fewer than half were interested.

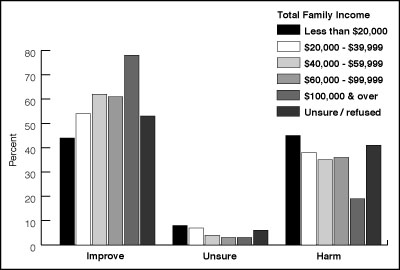

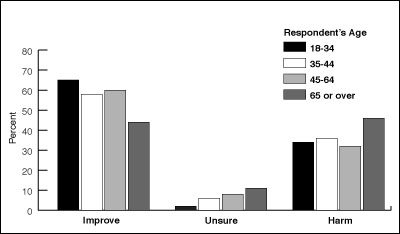

Is quality of life likely to be improved or harmed by research into cloning to provide cells that could be used to treat various diseases?

With this question, the variance in views among demographic groups is revealing. Among persons with incomes over $100,000 per year, 76 percent expect quality of life improvements, whereas only 45 percent among people with incomes under $20,000 share this expectation. Similarly, whereas 65 percent of those aged 18-34 expect improvement, only 43 percent of persons over 65 expect to have quality of life improved by cloning research. There is also a cloning gender gap: 66 percent of men, but only 49 percent of women, think cloning research will lead to improvements.

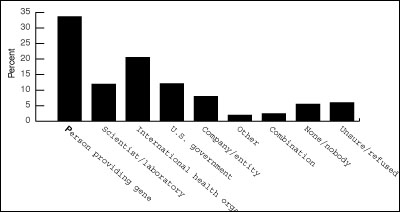

Who should have control over genes used in research?

Although distrust of international organizations is relatively common among Americans, in this case they seem to be more comfortable with international control than with their own government or corporations.

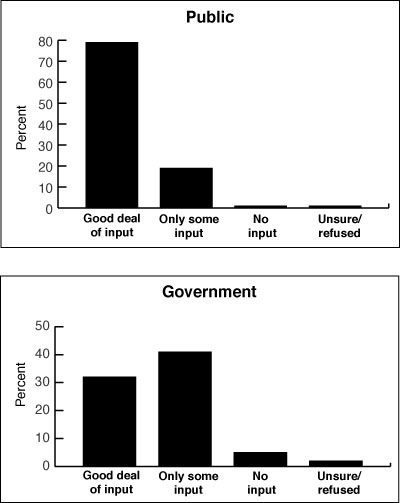

How much input should the public and the government have over technological change?

We apparently should spend more time polling the public about their views on S&T, because they clearly believe that they should be consulted. In fact, they are yet to be convinced that the government should have a prominent role.