A More Productive Way to Spread Federal Science Funding Around

Well-intentioned proposals to augment a program designed to equitably distribute research funding should take more deliberate steps to ensure R&D spending benefits the entire country.

In an age of many irreconcilable partisan divisions, lawmakers on Capitol Hill have quietly come to agree on at least one thing: the federal government must do more to shore up American science and technology. To that end, various pieces of bipartisan legislation aim to revitalize US research and development (R&D) by increasing funding for federal science agencies, particularly the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Against the backdrop of this consensus, a disagreement is now brewing about how to ensure that such spending increases benefit the whole country and not just those regions that have traditionally absorbed most federal R&D funding and the associated spillover benefits. Center stage in this debate is a relatively obscure NSF program known as the Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR). The purpose of the program is to counteract undue concentration of federal science funding, and it has been duplicated in several other science agencies.

Congress now has the opportunity to implement reforms to federal science agencies that could help distribute federal research investment across a more diverse array of institutions and geographies. These reform efforts should focus not only on mitigating geographic concentration but on diversifying federal science generally, injecting greater institutional and scientific pluralism into a system that has grown too concentrated and homogeneous. A reformed and expanded EPSCoR is the perfect place to start.

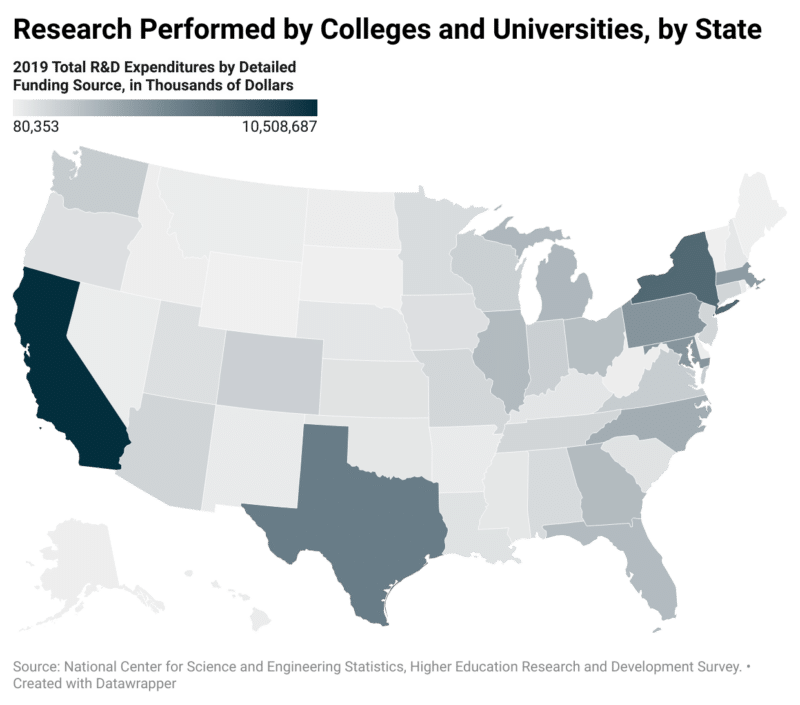

It is well known that federal R&D funding is highly concentrated around a handful of geographic regions and their most prominent institutions, including Johns Hopkins University, Duke University, and Columbia University and on the East Coast and Stanford University, the University of California, San Diego, and the University of Washington on the West Coast. Lack of diversity in R&D investment is not a new phenomenon. This trend goes back to the nineteenth century, when critics in Congress, especially southern Democrats, accused early federal science bureaus such as the US Coast and Geodetic Survey and the US Army’s Weather Bureau of corruption and favoritism, culminating in an official congressional investigation in the 1880s.

The issue returned in full force in the mid-twentieth century, after the government’s massive but highly concentrated research investments during the Second World War. Science reformers wanted to preserve the government’s generous wartime support while distributing federal funds more fairly. But they disagreed about how.

On one side, Sen. Harley M. Kilgore of West Virginia, a New Deal Democrat, called for the creation of a National Science Foundation. Kilgore’s NSF would disperse funding partly on a geographic basis, inspired by the example of federal agriculture research. It would also prioritize government research laboratories over nongovernmental science institutions such as universities and colleges. On the other side, Vannevar Bush, then the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, proposed in Science, the Endless Frontier a National Research Foundation that would fund nongovernmental research institutions on a meritocratic basis, regardless of geography.

Congress created the National Science Foundation in 1950, after years of wrangling. Despite taking Kilgore’s suggested name, the new agency bore the unmistakable imprint of Bush’s meritocratic vision. Yet in a nod to Kilgore, Congress also stipulated that the NSF “avoid undue concentration of research.” This provision provided the basis for NSF’s creation of EPSCoR 28 years later.

These reform efforts should focus not only on mitigating geographic concentration but on diversifying federal science generally

EPSCoR was designed to help regions traditionally underfunded by NSF compete more effectively for research dollars by providing money to improve infrastructure and capacity. Only states that have received less than 0.75% of the total NSF budget over a three-year period are eligible. The program, formally established by Congress in 1988, has grown in size and scope, with spin-off programs in several other science agencies. But has EPSCoR succeeded?

In 2010, Congress directed NSF to commission the National Academy of Sciences to assess the program and its spinoffs in other agencies. Although documenting numerous successes, the report found that “the aggregate share of federal R&D to eligible states has not changed significantly over the course of the program.”

In 2011, the NSF commissioned its own external assessment of its EPSCoR program. The conclusion of that report, released in 2014, was somewhat more positive. EPSCoR, the report found, had allowed for hiring faculty and expanding institutional capability through the creation of labs and centers. It also pointed to a “slight” decline in the geographic concentration of NSF’s R&D funding since 1980, and it showed that in early assessments (1980–1992), EPSCoR-eligible states had become more competitive for NSF funding. However, with respect to the declining concentration of R&D funding, the report concluded that “attribution of the decrease to EPSCoR could not be established” and that since 2000, year-over-year, eligible states had not become more competitive.

These are not glowing reviews—especially for a program that has existed for nearly half a century and consumes about $200 million per year, or 2% of NSF’s overall budget. While that may not sound like a lot of money, relatively speaking, consider that NSF’s entire internal operating budget is around $380 million annually.

EPSCoR was designed to help regions traditionally underfunded by NSF compete more effectively for research dollars by providing money to improve infrastructure and capacity.

EPSCoR is clearly doing some positive things for eligible states. But NSF and overall federal R&D funding remain highly concentrated, geographically and institutionally. Indeed, in 2019, more than half of all federally sourced higher education R&D expenditures were concentrated in just 10 states. And of the roughly 900 institutions of higher education that spent federal R&D money in 2019, 30 universities accounted for nearly half of that spending.

Despite limited evidence of success, EPSCoR remains politically popular. The Senate’s US Innovation and Competition Act bets big on the program, increasing funding for EPSCoR to a whopping 20% of NSF’s overall budget. The National Science Foundation for the Future Act, a rival bill in the House, boosts funding for EPSCoR as well, though it also emphasizes alternative programs to “build … research capacity” among underserved institutions. In a September mark-up, the House Science Committee expressed support for the Senate’s proposal to give EPSCoR a major boost.

Given EPSCoR’s modest track record, are these proposals likely to make a significant difference? To answer that question, it’s necessary to consider why the concentration of science funding is a problem in the first place.

Some observers might posit that an unequal distribution of federal grants is not a problem at all. It could simply mean that the best and brightest are getting what they deserve—redounding, presumably, to the benefit of all. Unequal distribution of rewards is arguably inherent in the meritocratic system of modern science—what the scientist and historian of science Derek J. de Solla Price once dubbed “undemocracy.” The concentration of federal funding could, in fact, be a sign that the system is working as it should: possibly a political problem, but no threat to science.

However, although an unequal distribution of scientific rewards may follow from meritocratic principles, such a distribution is not, in and of itself, evidence of meritocracy in action. The question that must be asked about the current system for distributing federal research dollars—and scientific rewards generally—is not whether its outcome is unequal but whether the system itself is, in fact, making the best science possible overall.

NSF and overall federal R&D funding remain highly concentrated, geographically and institutionally.

It is plausible that, as an increasing number of administrators are required to secure and manage external funding—a phenomenon that’s been referred to as “administrative bureaucratization”—those institutions capable of growing and sustaining such an apparatus (typically well-established, prestigious, and wealthy ones) may become the most successful in identifying, securing, and maintaining such funding. As a result, rewards become indicative not of scientific merit per se, but rather of bureaucratic effectiveness or even sheer financial wealth.

By itself, this does not show that the institutions most successful in securing funding or other rewards are necessarily undeserving. (Wealthy institutions may attract top faculty talent, for instance.) It does, however, strongly suggest that potentially deserving but less established, prestigious, or wealthy institutions are being denied fair opportunities to compete for such rewards.

The scientific enterprise is by nature “profoundly plural,” as historian A. Hunter Dupree once put it. As such, it tends to flourish in a decentralized environment, benefiting from the interplay of diverse communities of researchers within an array of institutional contexts. But what the United States has now is scientific research clustered around a relatively small number of elite and increasingly bureaucratic institutions.

Policymakers are right to worry about undue concentration of federal science funding—and not only for political reasons. It may be a sign of the erosion of that institutional pluralism which, at its best, has made the American system of scientific meritocracy so successful.

What can be done? EPSCoR programs preserve the federal research establishment’s traditional meritocratic system while trying to level the playing field so that a more diverse array of institutions (at least within certain states) can compete for federal research funding. But if geographic concentration is, at least in part, the result of underlying problems in how science’s meritocracy is currently organized, then it stands to reason that EPSCoR and its offshoots will struggle to reduce concentration on any meaningful scale. And indeed, the evidence suggests as much.

EPSCoR deserves continued support, but simply pouring more money into it is not the answer. Instead, lawmakers should consider how to reform the program and experiment with new ways to address various kinds of concentration and their root causes. NSF is open to reform. In May, EPSCoR announced a year-long “visioning process” intended to engage the “external stakeholder community to better understand the impacts of its investment strategies and identify new opportunities for increased success.” The goal is to discern whether there are “novel strategies” or “changes to current strategies” that would help NSF’s EPSCoR “to achieve its mission more effectively.”

EPSCoR deserves continued support, but simply pouring more money into it is not the answer.

Congress should seize this opportunity to build on and improve—not just increase funding for—EPSCoR and similar programs that aim to reduce undue concentration. In particular, EPSCoR should be expanded to encompass a wider range of programs aimed at experimenting with assessing and distributing federal R&D spending to supplement existing “meritocratic” funding mechanisms, and gathering evidence about what works. Such reforms might include the following provisions:

- Broadening EPSCoR’s focus to include efforts to reduce the undue concentration of federal funding in general, rather than geographic concentration at the state level, specifically. In particular, NSF should set aside more funding to help build infrastructure capacity for underserved institutions that may be disadvantaged in their grant applications by the size and inexperience of laboratories and primary investigators, regardless of whether they are located in EPSCoR states. This could help strike a compromise between the Senate’s US Innovation and Competition Act’s state-level focus on EPSCoR and the institution-level focus of the reforms proposed in the rival House bill.

- NSF could establish a “second look” program for grantees within (but not limited to) EPSCoR eligible jurisdictions. This could be done by placing a small percentage of well-qualified grant applicants who failed to receive federal funding in one of two new pilot programs.

- The first would be a modified lottery system, along the lines proposed by Ferric C. Fang and Arturo Casadevall, which uses peer review to identify the “most meritorious” proposals and selects a subset of these proposals to be awarded funding according to a lottery system.

- The second would experiment with reducing the regulatory burden for a similarly identified subset of well-qualified proposals by distributing awards as block grants without the traditional post-award administrative and reporting requirements that currently occupy nearly a quarter of researchers’ time (excluding fields subject to ethical requirements on animal testing and human subjects).

- Congress could earmark a small fixed percentage of new EPSCoR funding for traditionally underserved institutions, including but not limited to those currently in EPSCoR eligible jurisdictions. Following Mark P. Mills’s proposal, this program could disperse funding directly to these colleges and universities in the form of block grants, allowing “science-knowledge decision leaders” at these institutions to “identify, fund, and manage” scientific researchers and projects themselves.

- NSF could establish a pilot program that mirrors the NIH Director’s Pioneer Award, a “High-Risk, High-Reward Research program [that] supports scientists with outstanding records of creativity pursuing new research directions to develop pioneering approaches to major challenges.” While NSF supports early-stage researchers with the CAREER grant program, it should further support people rather than projects by funding late-career senior scientists to carry out high-risk, high-reward research in NSF’s own areas of focus and excellence. This sort of program could increase diversity within research, opening up new lines of inquiry.

- NSF’s office of Evaluation and Assessment Capability could coordinate with the Government Accountability Office’s Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics program to assess which policies prove most effective. Working with GAO as an external stakeholder would not only make use of that agency’s experience in providing independent analysis of technical issues, it would also demonstrate accountability to elected officials within Congress.

- Finally, those programs that show signs of success should be expanded and scaled beyond EPSCoR and considered for replication in other science agencies.

None of these reforms would be a silver bullet. But together, they could help pluralize federal science and produce a more diverse and heterogeneous system that embraces experimentation on all levels. The time is ripe to fix—and not simply fund—the American research establishment.