To Respond to the Pandemic, the Government Needs Better Data on Domestic Companies That Make Critical Medical Supplies

Real-time adaptive data collection capabilities could help policymakers guide decisions in the current health emergency and future crises.

Responding to a large-scale health emergency—such as the current COVID-19 pandemic—in a timely and efficient manner requires real-time data about the current state of manufacturing of critical medical supplies. Policymakers require such information to guide decisions to coordinate and mobilize additional capacity. Although existing public surveys—such as the Annual Survey of Manufacturers or the Economic Census—provide snapshots of US capabilities, they do not capture the rapidly evolving status of critical supply chains during a crisis. In addition, although the White House and entities such as the International Trade Commission can request information directly from companies, they are poorly equipped to do the frequent and comprehensive large-scale data collection needed to create a complete and accurate picture of an ever-changing situation. The result is that the US government is “flying blind,” lacking the necessary knowledge of the nation’s existing activities and capabilities to inform a policy response.

The US government is “flying blind,” lacking the necessary knowledge of the nation’s existing activities and capabilities to inform a policy response.

How bad is the government’s knowledge gap? To assess the potential scale of the gap on domestic manufacturing during the pandemic, we scraped data and did automated text analysis each week from Thomasnet, a leading North American Manufacturing industrial sourcing platform. Based on this data, we developed a list of firms that listed themselves as manufacturing face masks and N95 or other respirators, or the intermediate inputs needed therefore. We then corroborated this information and identified whether they were making the product of interest domestically, via additional searches on firm websites, filings with the Security Exchange Commission, data from D & B Hoovers, and interviews directly with companies.

Our investigation suggests that small- and medium-sized firms may be playing an important and poorly documented role in responding to the mask-and-respirator shortage associated with the pandemic. Even less well understood is the extent to which these and other firms could rapidly reorganize their production lines to meet newly pressing needs—as well as the sorts of policy actions and incentives that would work best to facilitate such a switch. To guide future policy decisions, including the coordination and mobilization of additional capacity, we recommend that Congress direct the US Department of Commerce to develop a strategy for the timely and adaptive assessment of US-based manufacturing capability of medical supplies for the duration of the present emergency, and document lessons to better support the creation of such an effort again in the event of a future emergency.

Overlooked, underused, and unknown

Government sources of firm data are useful to measure economic activity and composition in a steady state, but are not designed to capture rapid changes during emergencies. Currently, no public or proprietary data sources capture in real time the evolving universe of firms involved in supplying the US medical supply market. Once every five years, the US Census Bureau conducts the Economic Census, which captures all manufacturing plants in the economy (250,000+ plants). The survey and data collection methods are world class, but it can take more than two years to publish the results. The most recent Economic Census is from 2017. Summary data were released only in fall 2020, and additional data will be released on a flow basis through December 2021. The Annual Survey of Manufacturers is published more frequently, but is skewed toward the largest manufacturing plants (around 45,000 facilities). The survey was conducted in 2018 and published in April 2020. In addition, very few sources include reliable data on plant location and production capacity, and coverage within these is sparse.

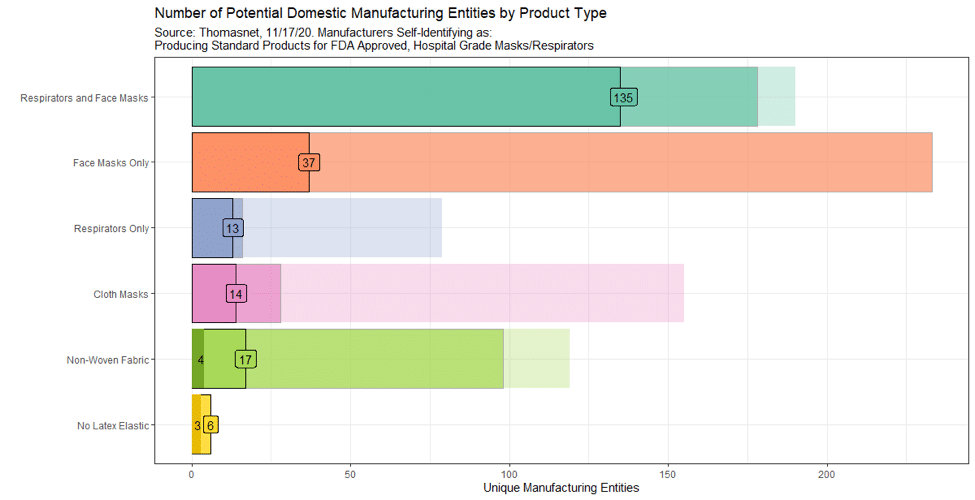

Previous work by Michael Gort and Steven Klepper and others used information from the Thomas Register of American Manufacturers to compile annual data on US-based producers of specific products. Similarly, we turned to Thomasnet to identify firms that manufacture masks, respirators, and their intermediate inputs in the United States.To begin to assess the consequences of spotty real-time data, we leveraged weekly web scraping and automated text analysis of Thomasnet to identify firms that self-identify as having domestic manufacturing of masks, respirators, and their intermediate inputs (see Figure 1). As categories are not precisely defined and firms may use different rules when reporting information to Thomasnet, we then checked the data against searches on the websites of various firms, information from D & B Hoovers, and interviews directly with companies. Here, particularly important was clarifying which Thomasnet-listed firms had domestic manufacturing facilities of the target medical supplies.

Figure 1 displays the results of our Thomasnet data collection and categorization algorithm. The faintest bars are the total number of manufacturing entities listed on Thomasnet as offering our target products (as listed on the y-axis). The faded bars are the number of manufacturing entities listed on Thomasnet that self-identify as serving the medical market or as matching our definition of meeting technical requirements for hospital grade masks and respirators. The outlined sections with the darkest coloring and a number show the subset of firms on Thomasnet with self-listed text that meets our definition for producing standard products for FDA-approved, hospital-grade masks or respirators.

As of November 16, we found that 56 Thomasnet-listed firms produced a product of interest at a domestic manufacturing facility. Forty-four firms manufactured respirators, masks, or both; seven manufactured nonwoven fabrics used in medical-grade masks; and five made nonlatex elastics. We were able to confirm exact geographic locations of plants for 32 of these 56 companies—information that may prove particularly helpful to local representatives in both federal and state governments as they respond to the pandemic. Our real-time data confirmed that the number of domestic manufacturers of each of these products has been increasing since the start of the pandemic.

Currently, no public or proprietary data sources capture in real time the evolving universe of firms involved in supplying the US medical supply market.

Comparing the Thomasnet data with White House data suggests substantial overlooked capacity. Of the 44 Thomasnet facilities producing respirators or masks domestically, only three are among the five largest firms (3M, Owens and Minor, Honeywell, Moldex, and Prestige America) that were used in White House estimates of production capacity in the early phase of the pandemic. Furthermore, our limited view from Thomasnet suggests that small- and medium-sized enterprises may be playing an important, albeit poorly documented, role in responding to mask and respirator shortages associated with the pandemic.

To support firms that are attempting to respond to the pandemic, whether by opening or repurposing domestic facilities, policymakers must first identify and develop an understanding of the universe of firms making such decisions. For example, three out of eight of the 44 Thomasnet companies for which we were able to find capacity information had recently purchased equipment to make masks or respirators in the United States. It’s unclear, however, to what extent these firms may be able to achieve their theoretical capacity.

An anecdote from a medium-sized US medical supply company illustrates the type of challenges these companies face in reshoring and pivoting to new products. Shortly before the pandemic, the company had imported enough equipment from China to manufacture 9 million ASTM Level 2 masks per month. The company planned to provide the masks at cost for the duration of the pandemic. With the pandemic in full swing, the company’s colleagues in China supported it in getting the equipment up and running. However, inability to gain access to a number of material inputs prevented the company from running at capacity.

Comparing the Thomasnet data with White House data suggests substantial overlooked capacity.

The company’s most challenging bottleneck was obtaining elastic for the ear loops, and not the highly publicized and technically challenging melt-blown polymer used in the mask itself. The elastic needed to be latex-free, come in a precise width and elasticity (stretchiness), and be available in bags to work in the automated machines. The company eventually found a domestic supplier for some of the necessary elastic, but that firm wasn’t able to provide the elastic at sufficient scale for 9 million masks. Furthermore, that firm’s elastic came on a spool, so for an extended time workers had to unspool the elastic by hand, with the associated productivity slowdown one would expect. By collecting data on capacity versus production, it would be possible to identify firms facing such challenges achieving their capacity—whether due to regulation, intermediate input supply, labor, critical technical knowledge, or otherwise. In addition, being able to adaptively add questions as awareness of issues change—for example, about challenges companies are facing—could further guide policymakers.

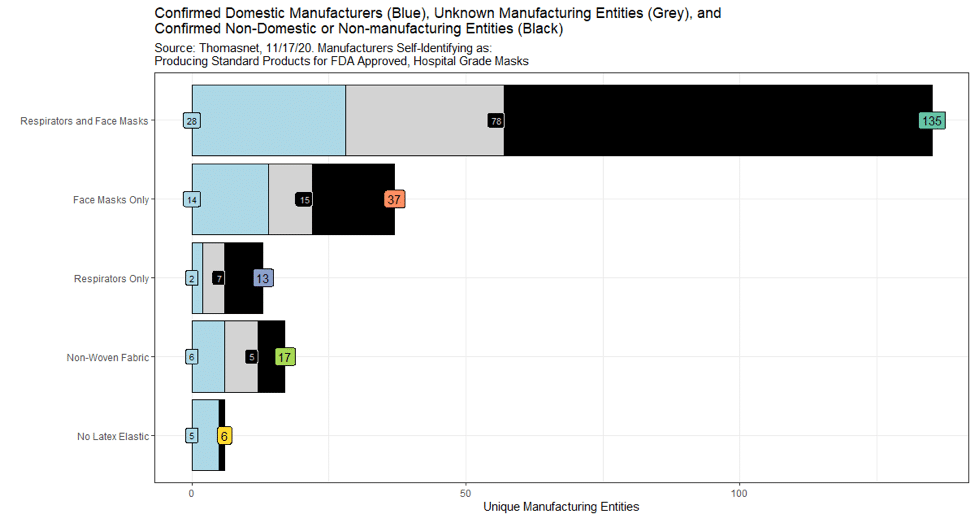

Our searches on firm’s websites, triangulation with data in D & B Hoovers, and interviews with companies allowed us to identify which firms are manufacturing domestically, and to understand what aspect of their production is actually domestic. Identifying what challenges may exist that prevent a company from moving manufacturing to the United States is an equally complex task. For example, Fulflex is a Thomasnet-listed manufacturer of latex-free elastics and nonwoven fabric, located in Brattleboro, Vermont.Fulflex serves a global market, and primarily relies on international production networks in Singapore and India to manufacture its products. Currently, Fulflex has domestic manufacturing capabilities, but they operate with much longer lead times than international facilities. As a consequence, while the company shows up in the figure as a domestic manufacturer of latex-free elastic (the blue group in Figure 2), the majority of that production occurs overseas.

“Unique Manufacturing Entities” on the x-axis represents firms that self-identify on ThomasNet as a manufacturer of standard FDA-approved, hospital-grade masks and respirators on November 17, 2020. The blue portion of the bar is the number of firms with confirmed production facilities in the United States. The black portion of the bar is the number of firms confirmed as a non-domestic or non-manufacturing entity. The grey portion represents companies whose production location we have yet to confirm.

Similarly, the Moore Co Textile Group is a leading manufacturer of elastic with a large selection of orthopedic and medical elastics (both pre-COVID and since the onset of the pandemic). Their primary manufacturing facilities are located in El Salvador, under an El Salvadorian division of the company. The US branch of this company consists of a “network of contract manufacturers that produce uniquely designed and qualified narrow elastics and webbings.” Through this network, the company can produce a product that qualifies under the Berry Amendment, which requires the Department of Defense to give preference in procurement to domestically produced, manufactured, or home-grown products. The Moore Co Textile Group currently does not count as a domestic manufacturer, but it may be well-placed to scale up domestic manufacturing in response to COVID-19, and also able to speak to the challenges of scaling-up domestic manufacturing. Here again, real-time adaptive data collection capabilities could support policymakers in changing the information sought so as to better understand what percentage of a firm’s intermediate inputs and final products are sourced domestically, the challenges these firms face in manufacturing domestically, and in asking direct questions about such challenges.

Thomasnet also offers a way to search for firms operating in closely relevant product spaces, and who thus may have the potential to pivot into addressing pressing needs. As of November 17, 185 firms described themselves on Thomasnet as being manufacturers of FDA-approved or hospital-grade face masks or respirators, a further 17 said they manufactured the melt-blown or spunbonded fabrics necessary for hospital-grade masks or respirators, and six manufactured no-latex elastic. An additional 250 firms described themselves as making masks, respirators, nonwoven fabrics, or latex-free elastic and listed themselves as serving medical markets or manufacturing products that would likely meet technical specifications for a hospital-grade face mask (243 mask or respirator firms and 7 nonwoven fabric firms). Further research would be required to understand which of these additional firms are already making hospital-grade masks or the intermediate inputs, which are trying to but facing challenges, and which are not yet producing medical supplies but with the right incentives and support might do so.

As demonstrated above, real-time adaptive data collection capabilities could revolutionize the ability of policymakers to understand the complete universe of domestic firms: which are already making hospital-grade masks or the intermediate inputs therefore, what challenges they face, and which are not yet producing medical supplies to meet pressing needs but presented with the right incentives and support might pivot to do so. This information is essential to guide decisions to coordinate and mobilize additional capacity in a health emergency or other crisis.

Blueprint for action

Congress should direct the US Department of Commerce to develop a strategy for timely and adaptive data collection of US-headquartered and US-located COVID-19 medical supply manufacturing capabilities for the duration of the emergency and document lessons that will allow the government to better support the creation of such an effort again in the event of a future emergency.

Real-time adaptive data collection capabilities could revolutionize the ability of policymakers to understand the complete universe of domestic firms.

The real-time data collection effort should include collecting information on the current production capacity of these companies in emergency-relevant intermediate inputs and final products. In addition to capacity, real-time data should be collected on actual production volumes in order to identify possible bottlenecks—regulatory, material, labor, knowledge, or otherwise—that are preventing firms from leveraging their full capacity.

Furthermore, it is essential for the data collection effort to be set up such that government agencies can easily adapt what information is collected. For example, as analysts learn about differences between equipment capacity and actual production, they may add questions about the obstacles that companies face in fully achieving their capacity. Or as analysts learn about complexities in domestic sourcing, they might seek information about what percentage of a firm’s intermediate inputs and final products are sourced domestically and the challenges it faces in manufacturing domestically. By combining this domestic production capability data with other readily available information (such as collected by Johns Hopkins University, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Department of Health and Human Services), local, state, and federal governments can develop more informed demand-side and supply-side policies to address gaps in a rapidly changing context.

Aggregate information on gaps between capacity and demand as well as on common challenges or bottlenecks should be communicated through a real-time dashboard to inform both the public and private sector. Along with the overall data collection effort, the dashboard would increase transparency, providing real-time information on where additional production and bottleneck-reducing innovations may be most valuable.

Finally, the Department of Commerce’s data collection and analysis activity must have a sunset clause such that it ends when the pandemic does.Ending the real-time data collection effort at the end of the pandemic will avoid continued expense without equivalent need (e.g., the rapidly changing environment of a pandemic is not the same as nonemergency periods). As part of the sunset clause, the individuals leading the effort should be required to systematically document lessons learned both for “steady-state” activities as well as for future crises. Here, future crises should include not just pandemics, but also natural disasters, war, and other undertakings where timely and adaptive collection and analysis of data may be essential to inform government decisions.

In responding to Congress’s mandate, the Department of Commerce should consider leveraging:

- Automated, large-scale data collection and analysis via market intermediaries of registered transactions.

- The US Census Bureau’s survey capabilities as well as its Registrar of Businesses, with a similar approach and (most importantly) speed as was achieved for the COVID-19 Small Business Pulse Survey.

- A public-private partnership that brings together the large-scale data collection and analysis capabilities available in academia and industry (e.g., Google, Microsoft, or Amazon) with government entities that have access to or are seeking to act on this information.

- The National Institute of Standards and Technology, given its existing role leading Manufacturing USA (formerly, the National Network of Manufacturing Innovation Institutes) as well as governing the Manufacturing Extension Program.

By combining this domestic production capability data with other readily available information governments can develop more informed demand-side and supply-side policies to address gaps in a rapidly changing context.

The data challenges hindering government decisionmaking under the current COVID-19 crisis are not unique. Agencies as diverse as the US Departments of Defense, Commerce (including the Economic Census and International Trade Commission), Transportation, Energy, and Homeland Security (including the Federal Emergency Management Agency) can benefit from harnessing emerging state-of-the-art data collection and analytics capabilities. Whereas the Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Government Act of 2019 (S. 1363) creates a new office in the General Services Administration “to promote adoption, use, competency, and cohesion of Federal Government applications of artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance productivity and efficiency of government operations for the public benefit,” those efforts are still in their infancy.

Achieving the goals of this legislation will take a long time, with many obstacles and lessons learned. A 2018 report from the MITRE corporation unpacks how intra- and intergovernmental actions and knowledge pertaining to critical supply chains are uncoordinated and isolated from each other. Further, a 2020 report by Kathy Stack, formerly of the Office and Management and Budget, demonstrated how government programs underperform because of challenges integrating data across agencies and levels of federal, state, and local government. Tackling these obstacles alone will be challenging. Even more ambitious initiatives might be able to leverage machine learning and novel data collection and analytics to tackle much more challenging pressures, such as strategic opportunities and weaknesses versus other nations. (In the inaugural session of the National Academies’ study on Science and Innovation Leadership for the 21st Century, representatives from the DOD’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Strategic Technology Protection and Exploitation Office both said that they lacked the mechanisms and ability to assess their strategic weaknesses and opportunities versus other nations in technologies critical to national security.) Assuming our proposal is adopted, the information collected and analyzed and lessons learned from ramping up real-time data and analytics capabilities during the COVID-19 emergency will offer important lessons for future government responses to a wide variety of crises.