Natural Histories

400 Years of Scientific Illustration from the Museum’s Library

In a time of the internet, social media networks, and smart phones, when miraculous devices demand our attention with beeps, buzzes, and spiffy animations, it’s hard to imagine a time when something as quiet and unassuming as a book illustration was considered cutting-edge technology. Yet, since the early 1500s, illustration has been essential to scientists for sharing their work with colleagues and with the public.

Young Hippo This image from the Zoological Society of London provides two views of a young hippo in Egypt before being transported to the London Zoo. Joseph Wolf (1820–1899) based the image on a sketch made by the British Consul on site in Cairo.

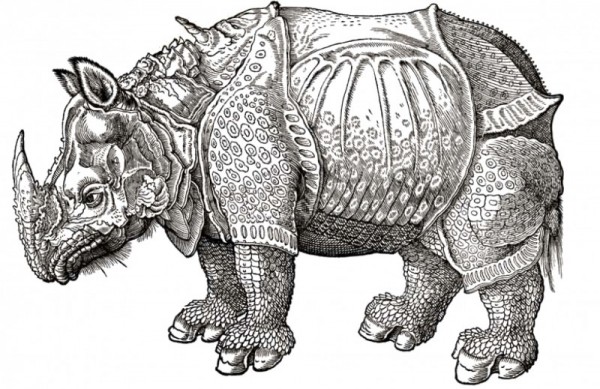

Rhino by Dürer This depiction of a rhino from Historia animalium, by German artist Albrecht Dürer, inaccurately features ornate armor, scaly skin, and odd protrusions.

Mandrill This mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx), with its delicate hands, cheerful expression, and almost upright posture, seems oddly human. While many images in Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber’s Mammals Illustrated (1774–1846) were quite accurate, those of primates generally were not.

Darwin’s Rhea John Gould drew this image of a Rhea pennata, a flightless bird native to South America, for The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle (1839–1843), a five-volume work edited by Charles Darwin. The specimens Darwin collected during his travels on H.M.S. Beagle became a foundation for Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection.

The nearly forgotten books stored away quietly in libraries contain the ancestral ideas of current practices and methodologies of illustration.

A variety of printing techniques, ranging from woodcuts to engraving to lithography, proved highly effective for spreading new knowledge about nature and human culture to a growing audience. Illustrated books allowed the lay public to share in the excitement of discoveries, from Antarctica to the Amazon, from the largest life forms to the microscopic.

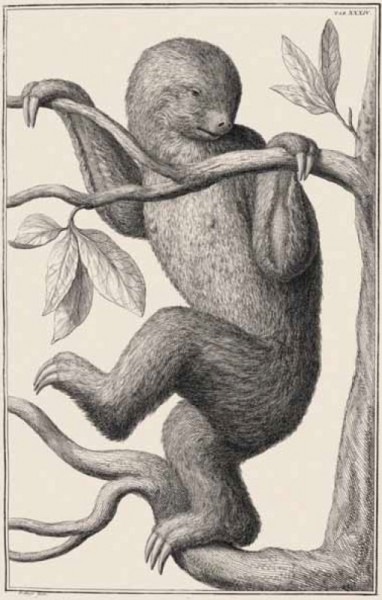

Two-toed Sloth Albertus Seba’s (1665–1736) four-volume Thesaurus (after Thesaurus of animal specimens) illustrated the Dutch apothecary’s enormous collection of animal and plant specimens amassed over the years. Using preserved specimens, Seba’s artists could depict anatomy accurately—but not behavior. For example, this two-toed sloth is shown climbing upright, even though in nature, sloths hang upside down.

The early impact of illustration in research, education, and communication arguably formed the foundation for how current illustration and imaging techniques are utilized today. Now scientists have a vast number of imaging tools that are harnessed in a variety of ways: infrared photography, scanning electron microscopes, computed tomography scanners and more. But there is still a role for illustration in making the invisible visible. How else can we depict extinct species such as dinosaurs?

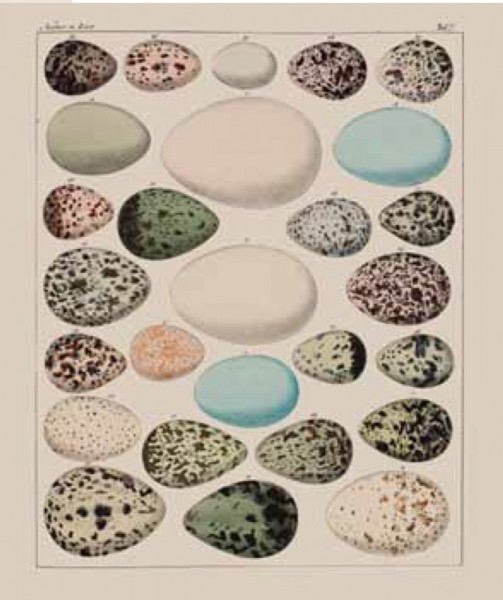

Egg Collection In his major encyclopedia of nature, Allgemeine Naturgeschichte für alle Stände (A general natural history for everyone), German naturalist Lorenz Oken (1779–1851) grouped animals based not on science, but philosophy. Nevertheless, his encyclopedia proved to be a popular and enduring work. Here Oken is illustrating variation in egg color and markings found among water birds.

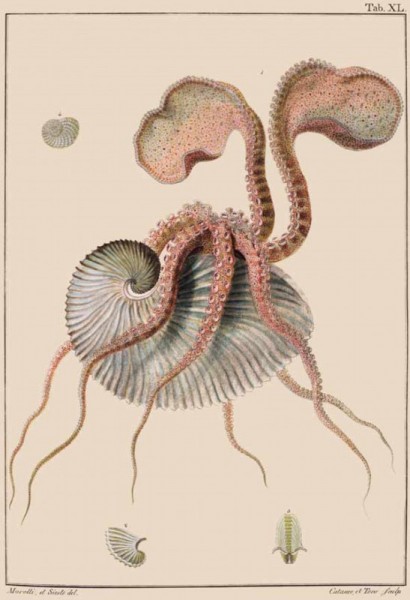

Paper Nautilus Italian naturalist Giuseppe Saverio Poli (1746–1825) is considered to be the father of malacology—the study of mollusks. In his landmark work Testacea utriusque Siciliae…(Shelled animals of the Two Sicilies…), Poli first categorized mollusks by their internal structure, and not just their shells, as seen in his detailed illustration of female paper nautilus (Argonauta argo).

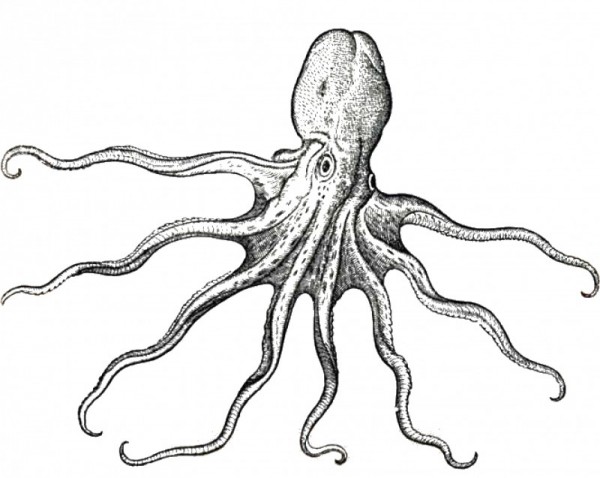

Octopus From Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium (1551–1558), this octopus engraving is a remarkably good likeness—except for the depiction of round, rather than slit-shaped, pupils—indicating the artist clearly did not draw from a live specimen.

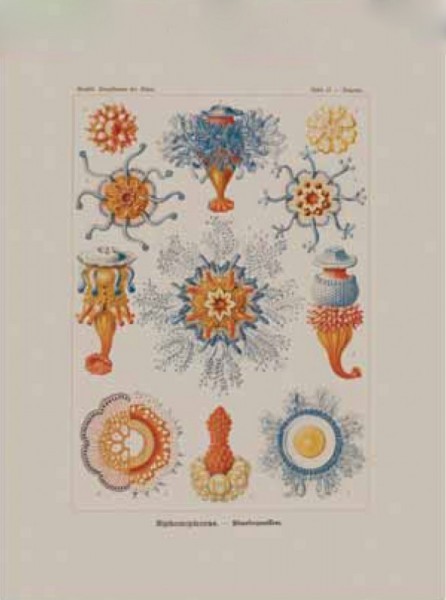

Siphonophores German biologist Ernst Haeckel illustrated and described thousands of deep-sea specimens collected during the 1873–1876 H.M.S. Challenger expedition, and used many of those images to create Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms of nature). Haeckel used a microscope to capture the intricate structure of these siphonophores—colonies of tiny, tightly packed and highly specialized organisms—that look (and sting!) like sea jellies.

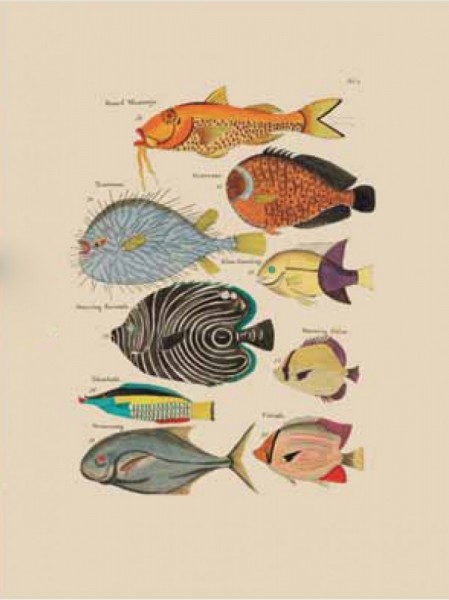

Angry Puffer Fish and Others Louis Renard’s artists embellished their work to satisfy Europeans’ thirst for the unusual. Some illustrations in Poissons, écrevisses et crabes, de diverses couleurs et figures extraordinaires…, like this one, include fish with imaginative colors and patterns and strange, un-fishlike expressions.

Illustration is also used to clearly represent complex structures, color graduations, and other essential details. The nearly forgotten books stored away quietly in libraries contain the ancestral ideas of current practices and methodologies of illustration.

In the days before photography and printing, original art was the only way to capture the likeness of organisms, people, and places, and therefore the only way to share this information with others,” said Tom Baione, the Harold Boeschenstein Director of the Department of Library Services at the American Museum of Natural History. “Printed reproductions of art about natural history enabled many who’d never seen an octopus, for example, to try to begin to understand what an octopus looked like and how its unusual features might function.”

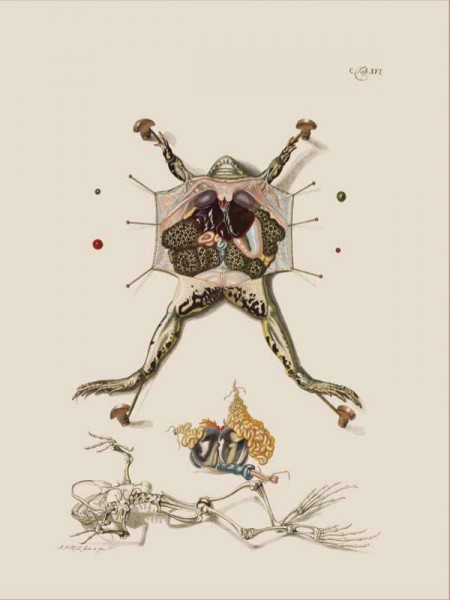

Frog Dissection A female green frog (Pelophylax kl. esculentus) with egg masses is shown in dissection above a view of the frog’s skeleton in the book Historia naturalis ranarum nostratium…(Natural history of the native frogs…) from 1758. Shadows and dissecting pins add to the realism.

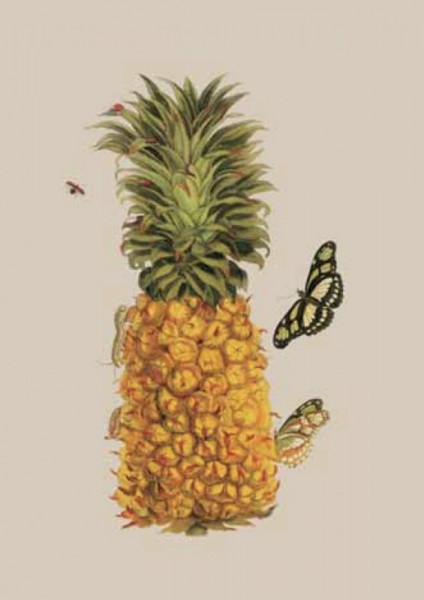

Pineapple with Caterpillar In Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium…(1719), German naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian documented the flora and fauna she encountered during her two-year trip to Surinam, in South America, with her daughter. Here she creatively depicts a pineapple hosting a butterfly and a red-winged insect, both shown in various stages of life.

The impact and appeal of printing technologies is at the heart of the 2012 book edited by Tom Baione, Natural Histories: Extraordinary Rare Book Selections from the American Museum of Natural History Library. Inspired by the book, the current exhibit at the museum, Natural Histories: 400 Years of Scientific Illustration from the Museum’s Library, explores the integral role illustration has played in scientific discovery through 50 large-format reproductions from seminal holdings in the Museum Library’s Rare Book collection. The exhibition is on view through October 12, 2014 at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. All images © AMNHD. Finnin.

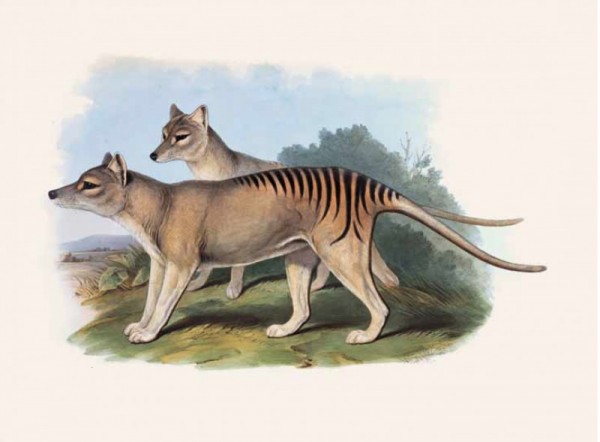

Tasmanian Tiger English ornithologist and taxidermist John Gould’s images and descriptions for the three-volume work The mammals of Australia (1863) remain an invaluable record of Australian animals that became increasingly rare with European settlement. The “Tasmanian tiger” pictured here was actually a thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), the world’s largest meat-eating marsupial until going extinct in 1936.

JUSTINE SEREBRIN, Gateway, Digital painting, 40 × 25 inches, 2013.