Building on Medicare’s Strengths

Reform is needed, but the program’s core principles and essential components must be preserved.

The aging of the U.S. population will generate many challenges in the years ahead, but none more dramatic than the costs of providing health care services for older Americans. Largely because of advances in medicine and technology, spending on both the old and the young has grown at a rate faster than spending on other goods and services. Combining a population that will increasingly be over the age of 65 with health care costs that will probably continue to rise over time is certain to mean an increasing share of national resources devoted to this group. In order to meet this challenge, the nation must plan how to share that burden and adapt Medicare to meet new demands.

Projections from the 1999 Medicare Trustees Report indicate that Medicare’s share of the gross domestic product (GDP) will reach 4.43 percent in 2025, up from 2.53 percent in 1998. Although this is a substantial increase, it is actually smaller than what was being projected a few years ago. This slowdown in growth does not eliminate the need to act, but it does allow some time for study and deliberation before we do act.

Projected increases in Medicare’s spending arise because of the high costs of health care and growing numbers of people eligible for the program. But most of the debate over Medicare reform centers on restructuring of Medicare. This restructuring would rely on contracting with private insurance plans, which would compete for enrollees. The federal government would subsidize a share of the costs of an average plan, leaving beneficiaries to pay the remainder. More expensive plans would require beneficiaries to pay higher premiums. The goal of such an approach is to make both plans and beneficiaries sensitive to the costs of care, leading to greater efficiency. But this is likely to address only part of the reason for higher costs of care over time. Claims for savings from options that shift Medicare more to a system of private insurance usually rest on two basic arguments: First, it is commonly claimed that the private sector is more efficient than Medicare, and second, that competition among plans will generate more price sensitivity on the part of beneficiaries and plans alike. Although seemingly credible, these claims do not hold up under close examination.

Medicare efficiency

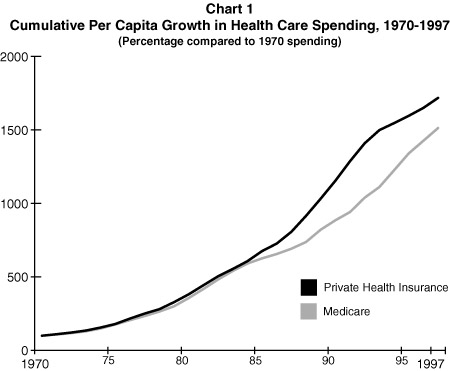

Looking back over the period from 1970 to 1997, Medicare’s cost containment performance has been better than that of private insurance. Starting in the 1970s, Medicare and private insurance plans initially grew very much in tandem, showing few discernible differences (see Chart 1). By the 1980s, per capita spending had more than doubled in both sectors. But Medicare became more cost-conscious than private health insurance in the 1980s; and cost containment efforts, particularly through hospital payment reforms, began to pay off. From about 1984 through 1988, Medicare’s per capita costs grew much more slowly than those in the private sector.

This gap in overall growth in Medicare’s favor stayed relatively constant until the early 1990s, when private insurers began to take the rising costs of health insurance seriously. At that time, growth in the cost of private insurance moderated in a fashion similar to Medicare’s slower growth in the 1980s. Thus, it can be argued that the private sector was playing catch-up to Medicare in achieving cost containment. Private insurance thus narrowed the difference with Medicare in the 1990s, but as of 1997 there was still a considerable way for the private sector to go before its cost growth would match Medicare’s achievement of lower overall growth.

It should not be surprising that the per capita rates over time are similar between Medicare and private sector spending, because all health care spending shares technological change and improvement as a major factor driving high rates of expenditure growth. To date, most of the cost savings generated by all payers for care has come from slowing growth in the prices paid for services but making only preliminary inroads in reducing the use of services or addressing the issue of technology. Reining in the use of services will be a major challenge for private insurance as well as Medicare in the future, and it is not clear whether the public or private sector is better equipped to do this. Further, Medicare’s experience with private plans has been distinctly mixed.

Reform options such as the premium support approach seek savings by allowing the premiums paid by beneficiaries to vary so that those choosing higher-cost plans pay substantially higher premiums. The theory is that beneficiaries will become more price conscious and choose lower-cost plans. This in turn will reward private insurers that are able to hold down costs. And there is some evidence from the federal employee system and the Calpers system in California that this has disciplined the insurance market to some degree. Studies that have focused on retirees, however, show much less sensitivity to price differences. Older people may be less willing to change doctors and learn new insurance rules in order to save a few dollars each month. Thus, what is not known is how well this will work for Medicare beneficiaries.

For example, for a premium support model to work, at least some beneficiaries must be willing to shift plans each year (and to change providers and learn new rules) in order to reward the more efficient plans. Without that shifting, savings will not occur. In addition, there is the question of how private insurers will respond. (If new enrollees go into such plans each year, some savings will be achieved, but these are the least costly beneficiaries and may lead to further problems as discussed below.) Will they seek to improve service or instead focus on marketing and other techniques to attract a desirable, healthy patient base? It simply isn’t known whether competition will really do what it is supposed to do.

In addition, new approaches to the delivery of health care under Medicare may generate a whole new set of problems, including problems in areas where Medicare is now working well. For example, shifting across plans is not necessarily good for patients; it is not only disruptive, it can raise the costs of care. Some studies have shown that having one physician over a long period of time reduces the costs of care. And if only the healthier beneficiaries choose to switch plans, the sickest and most vulnerable beneficiaries may end up being concentrated in plans that become increasingly expensive over time. The case of retirees left in the federal employee high-option Blue Cross plan and in a study of retirees in California suggest that even when plans become very expensive, beneficiaries may be fearful of switching and end up substantially disadvantaged. Further, private plans by design are interested in satisfying their own customers and generating profits for stockholders. They cannot be expected to meet larger social goals such as making sure that the sickest beneficiaries get high-quality care; and to the extent that such goals remain important, reforms in Medicare will have to incorporate additional protections to balance these concerns as described below.

Core principles

The reason to save Medicare is to retain for future generations the qualities of the program that are valued by Americans and that have served them well over the past 33 years. This means that any reform proposal ought to be judged on principles that go well beyond the savings that they might generate for the federal government.

I stress three crucial principles that are integrally related to Medicare’s role as a social insurance program:

- The universal nature of the program and its consequent redistributive function.

- The pooling of risks that Medicare has achieved to share the burdens across sick and healthy enrollees.

- The role of government in protecting the rights of beneficiaries–often referred to as its entitlement nature.

Although there are clearly other goals and contributions of Medicare, these three are part of its essential core. Traditional Medicare, designed as a social insurance program, has done well in meeting these goals. What about options relying more on the private sector?

Universality and redistribution. An essential characteristic of social insurance that Americans have long accepted is the sense that once the criterion for eligibility of contributing to the program has been met, benefits will be available to all beneficiaries. One of Medicare’s great strengths has been providing much-improved access to health care. Before Medicare’s passage, many elderly people could not afford insurance, and others were denied coverage as poor risks. That changed in 1966 and had a profound impact on the lives of millions of seniors. The desegregation of many hospitals occurred on Medicare’s watch. And although there is substantial variation in the ability of beneficiaries to supplement Medicare’s basic benefits, basic care is available to all who carry a Medicare card. Hospitals, physicians, and other providers largely accept the card without question.

Once on Medicare, enrollees no longer have to fear that illness or high medical expenses could lead to the loss of coverage–a problem that still happens too often in the private sector. This assurance is an extremely important benefit to many older Americans and persons with disabilities. Developing a major health problem is not grounds for losing the card; in fact, in the case of the disabled, it is grounds for coverage. This is vastly different than the philosophy of the private sector toward health coverage. Even though many private insurers are willing and able to care for Medicare patients, the easiest way to stay in business as an insurer is to seek out the healthy and avoid the sick.

Will reforms that lead to a greater reliance on the market still retain the emphasis on equal access to care and plans? For example, differential premiums could undermine some of the redistributive nature of the program that assures even low-income beneficiaries access to high-quality care and responsive providers.

The pooling of risks. One of Medicare’s important features is the achievement of a pooling of risks among the healthy and sick covered by the program. Even among the oldest of the beneficiaries, there is a broad continuum across individuals’ needs for care. Although some of this distribution is totally unpredictable (because even people who have historically had few health problems can be stricken with catastrophic health expenses), a large portion of seniors and disabled people have chronic problems that are known to be costly to treat. If these individuals can be identified and segregated, the costs of their care can expand beyond the ability of even well-off individuals to pay over time.

A major impetus for Medicare was the need to protect the most vulnerable. That’s why the program focused exclusively on the old in 1965 and then added the disabled in 1972. About one in every three Medicare beneficiaries has severe mental or physical health problems. In contrast, the healthy and relatively well-off (with incomes over $32,000 per year for singles and $40,000 per year for couples) make up less than 10 percent of the Medicare population. Consequently, anything that puts the sickest at greater risk relative to the healthy is out of sync with this basic tenet of Medicare. A key test of any reform should be whom it best serves.

If the advantages of one large risk pool (such as the traditional Medicare program) are eliminated, other means will have to be found to make sure that insurers cannot find ways to serve only the healthy population. Although this very difficult challenge has been studied extensively, as yet no satisfactory risk adjustor has been developed. What has been developed to a finer degree, however, are marketing tools and mechanisms to select risks. High-quality plans that attract people with extensive health care needs are likely to be more expensive than plans that focus on serving the relatively healthy. If risk adjustors are never powerful enough to eliminate these distinctions and level the playing field, then those with health problems, who also disproportionately have lower incomes, would have to pay the highest prices under many reform schemes.

The role of government. Related to the two principles above is the role that government has played in protecting beneficiaries. In traditional Medicare, this has meant having rules that apply consistently to individuals and ensure that everyone in the program has access to care. It has sometimes fallen short in terms of the variations that occur around the country in benefits, in part because of interpretation of coverage decisions but also because of differences in the practice of medicine. For example, rates of hospitalization, frequency of operations such as hysterectomies, and access to new tests and procedures vary widely by region, race, and other characteristics. But in general Medicare has to meet substantial standards of accountability that protect its beneficiaries.

If the day-to-day provision of care is left to the oversight of private insurers, what will be the impact on beneficiaries? It is not clear whether the government will be able to provide sufficient oversight to protect beneficiaries and ensure them of access to high-quality care. If an independent board–which is part of many restructuring proposals–is established to negotiate with plans and oversee their performance, to whom will it be accountable? Further, what provisions will be in place to step in when plans fail to meet requirements or leave an area abruptly? What recourse will patients have when they are denied care?

One of the advantages touted for private plans is their ability to be flexible and even arbitrary in making decisions. This allows private insurers to respond more quickly than a large government program and to intervene where they believe too much care is being delivered. But what look like cost-effectiveness activities from an insurer’s perspective may be seen by a beneficiary as the loss of potentially essential care. Which is more alarming: too much care or care denied that cannot be corrected later? Some of the “inefficiencies” in the health care system may be viewed as a reasonable response to uncertainty when the costs of doing too little can be very high indeed.

Preserving what works

Much of the debate over how to reform the Medicare program has focused on broad restructuring proposals. However, it is useful to think about reform in terms of a continuum of options that vary in their reliance on private insurance. Few advocate a fully private approach with little oversight; similarly, few advocate moving back to 1965 Medicare with its unfettered fee-for-service and absence of any private plan options. In between, however, are many possible options and variations. And although the differences may seem technical or obscure, many of these “details” matter a great deal in terms of how the program will change over time and how well beneficiaries will be protected. Perhaps the most crucial issue is how the traditional Medicare program is treated. Under the current Medicare-plus-Choice arrangement, beneficiaries are automatically enrolled in traditional Medicare unless they choose to go into a private plan. Alternatively, traditional Medicare could become just one of many plans that beneficiaries choose among–but probably paying a substantially higher premium if they choose to do so.

What are the tradeoffs from increasingly relying on private plans to serve Medicare beneficiaries? The modest gains in lower costs that are likely to come from some increased competition and from the flexibility that the private sector enjoys could be more than offset by the loss of social insurance protection. The effort necessary to create in a private plan environment all the protections needed to compensate for moving away from traditional Medicare seems too great and too uncertain. And on a practical note, many of the provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 that would be essential in any further moves to emphasize private insurance–generating new ways of paying private plans, improving risk adjustment, and developing information for beneficiaries, for example–still need a lot of work.

In addition, it is not clear that there is a full appreciation by policymakers or the public at large of all the consequences of a competitive market. Choice among competing plans and the discipline that such competition can bring to prices and innovation are often stressed as potential advantages of relying on private plans for serving the Medicare population. But if there is to be choice and competition, some plans will not do well in a particular market, and as a result they will leave. In a market system, withdrawals should be expected; indeed, they are a natural part of the process by which uncompetitive plans that cannot attract enough enrollees leave particular markets. If HMOs have a hard time working with doctors, hospitals, and other providers in an area, they may decide that this is not a good market. And if they cannot attract enough enrollees to justify their overhead and administrative expenses, they will also leave an area. The whole idea of competition is that some plans will do well and in the process drive others out of those areas. In fact, if no plans ever left, that would be a sign that competition was not working well.

But plan withdrawals will result in disruptions and complaints by beneficiaries, much like those now occurring in response to the recently announced withdrawals from Medicare-plus-Choice. For various reasons, private plans can choose each year not to accept Medicare patients. In each of the past two years, about 100 plans around the country have decided to end their Medicare businesses in some or all of the counties they serve. In those cases, beneficiaries must find another private plan or return to traditional Medicare. They may have to choose new doctors and learn new rules. This situation has led to politically charged discussions about payment levels in the program, even though that is only one of many factors that may cause plans to withdraw. Thus, not only will beneficiaries be unhappy, but there may be strong political pressure to keep federal payments higher than a well-functioning market would require.

What I would prefer to see is an emphasis on improvements in the private plan options and the traditional Medicare program, basically retaining the current structure in which traditional Medicare is the primary option. Rather than focusing on restructuring Medicare to emphasize private insurance, I would place the emphasis on innovations necessary for improvements in health care delivery regardless of setting.

That is, better norms and standards of care are needed if we are to provide quality-of-care protections to all Americans. Investment in outcomes research, disease management, and other techniques that could lead to improvements in treatment of patients will require a substantial public commitment. This cannot be done as well in a proprietary for-profit environment where new ways of coordinating care may not be shared. Private plans can play an important role and may develop some innovations on their own, but in much the same way as we view basic research on medicine as requiring a public component, innovations in health care delivery also need such support. Further, innovations in treatment and coordination of care should focus on those with substantial health problems–exactly the population that many private plans seek to avoid. Some private plans might be willing to specialize in individuals with specific needs, but this is not going to happen if the environment is one that emphasizes price competition and has barely adequate risk adjusters. Innovative plans would be likely to suffer in that environment.

Finally, the default plan–for those who do not or cannot choose or who find a hostile environment in the world of competition–must, at least for the time being, be traditional Medicare. Thus, there needs to be a strong commitment to maintaining a traditional Medicare program while seeking to define the appropriate role for alternative options. But for the time being, there cannot and should not be a level playing field between traditional Medicare and private plans. Indeed, if Medicare truly used its market power as do other dominant firms in an industry, it could set its prices in markets in order to drive out competitors, or it could sign exclusive contracts with providers, squeezing out private plans. When private plans suggest that Medicare should compete on a level playing field, it is unlikely that they mean this to be taken literally.

Other reform issues

Although most of the attention given to reform focuses on structural questions, there are other key issues that must also be addressed, including the adequacy of benefits, provisions that pass costs on to beneficiaries, and the need for more general financing. Even after accounting for changes that may improve the efficiency of the Medicare program through either structural or incremental reforms, the costs of health care for this population group will still probably grow as a share of GDP. That will mean that the important issue of who will pay for this health care–beneficiaries, taxpayers, or a combination of the two–must ultimately be addressed to resolve Medicare’s future.

Improved benefits. It is hard to imagine a reformed Medicare program that does not address two key areas of coverage: prescription drugs and a limit on the out-of-pocket costs that any individual beneficiary must pay in a year. Critics of Medicare rightly point out that its inadequacy has led to the development of a variety of supplemental insurance arrangements, which in turn create an inefficient system in which most beneficiaries rely on two sources of insurance to meet their needs. Further, without a comprehensive benefit package that includes those elements of care that are likely to naturally attract sicker patients, viable competition without risk selection will be difficult to attain.

It is sometimes argued that improvements in coverage can occur only in combination with structural reform. And some advocates of a private approach to insurance go further, suggesting that the structural reform itself will naturally produce such benefit improvements. This implicitly holds the debate on improved benefits hostage to accepting other unrelated changes. And to suggest that a change in structure, without any further financial contributions to support expanded benefits, will yield large expansions in benefits is wishful thinking. A system designed to foster price competition is unlikely to stimulate expansion of benefits.

Expanding benefits is a separable issue from how the structure of the program evolves over time. However, it is not separable from the issue of the cost of new benefits. This is quite simply a financing issue, and it would require new revenues, probably from a combination of beneficiary and taxpayer dollars. A voluntary approach to providing such benefits through private insurance, such as we have at present, is seriously flawed. For example, prescription drug benefits generate risk selection problems; already the costs charged by many private supplemental plans for prescription drugs equal or outweigh their total possible benefits because such coverage attracts a sicker-than-average set of enrollees. A concerted effort to expand benefits is necessary if Medicare is to be an efficient and effective program.

Disability beneficiaries. A number of special problems face the under-65 disabled population on Medicare. The 18-month waiting period before a Social Security disability recipient becomes eligible for coverage creates severe hardships for some beneficiaries who must pay enormous costs out of pocket or delay treatments that could improve their disabilities if they do not have access to other insurance. In addition, a disproportionate share of the disability population has mental health needs, and Medicare’s benefits in this area are seriously lacking. Special attention to the needs of this population should not get lost in the broader debate.

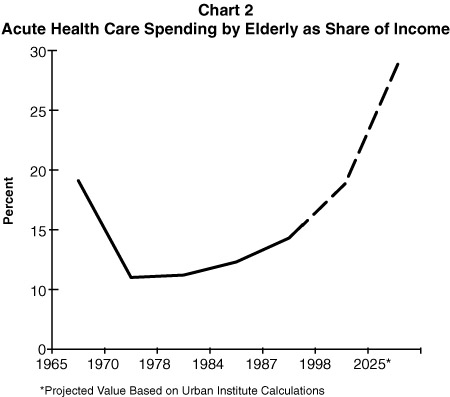

Beneficiaries’ contributions. Some piece of a long-term solution probably will (and should) include further increases in contributions from beneficiaries beyond what is already scheduled to go into place. The question is how to do so fairly. Options for passing more costs of the program on to beneficiaries, either directly through new premiums or cost sharing or indirectly through options that place them at risk for health care costs over time, need to be carefully balanced against beneficiaries’ ability to absorb these changes. Just as Medicare’s costs will rise to unprecedented levels in the future, so will the burdens on beneficiaries and their families. Even under current law, Medicare beneficiaries will be paying a larger share of the overall costs of the program and spending more of their incomes in meeting these health care expenses (see Chart 2).

In addition, options to increase beneficiary contributions to the cost of Medicare further increase the need to provide protections for low-income beneficiaries. The current programs to provide protections to low-income beneficiaries are inadequate, particularly if new premium or cost-sharing requirements are added to the program. Participation in this program is low, probably in part because it is housed in the Medicaid program and is thus tainted by its association with a “welfare” program. Further, states, which pay part of the costs, tend to be unenthusiastic about it and probably also discourage participation.

Financing. Last but not least, Medicare’s financing must be part of any discussion about the future. We simply cannot expect as a society to provide care to the most needy of our citizens for services that are likely to rise in costs and to absorb a rapid increase in the number of individuals becoming eligible for Medicare without facing the financing issue head on. Medicare now serves one in every eight Americans; by 2030 it will serve nearly one in every four. And these people will need to get care somewhere. If not through Medicare, then where?