In the Zone: Comprehensive Ocean Protection

Comprehensive ecosystem-based zoning could address many of the critical problems with U.S. ocean policy by providing a mechanism for coordinated management of ocean uses that takes into account the cumulative effects of multiple human activities.

For too long, humanity’s effects on the oceans have been out of sight and out of mind. Looking at the vast ocean from the shore or a jet’s window, it is hard to imagine that this seemingly limitless area could be vulnerable to human activities. But during the past decade, reports have highlighted the consequences of human activity on our coasts and oceans, including collapsing fisheries, invasive species, unnatural warming and acidification, and ubiquitous “dead zones” induced by nutrient runoff. These changes have been linked not to a single threat but to the combined effects of the many past and present human activities that affect marine ecosystems directly and indirectly.

The declining state of the oceans is not solely a conservation concern. Healthy oceans are vital to everyone, even those who live far from the coast. More than 1 billion people worldwide depend on fish as their primary protein source. The ocean is a key component of the climate system, absorbing solar radiation and exchanging, absorbing, and emitting oxygen and carbon dioxide. Ocean and coastal ecosystems provide water purification and waste treatment, land protection, nutrient cycling, and pharmaceutical, energy, and mineral resources. Further, more than 89 million Americans and millions more around the world participate in marine recreation each year. As coastal populations and demand for ocean resources have grown, more and more human activities now overlap and interact in the marine environment.

Integrated management of these activities and their effects is necessary but is just beginning to emerge. In Boston Harbor, for example, a complicated mesh of navigation channels, offshore dumping sites, outflow pipes, and recreational and commercial vessels crisscrosses the bay. Massachusetts, like other states and regions, has realized the potential for conflict in this situation and is adopting a more integrated framework for managing these and future uses in the harbor and beyond. In 2007, California, Oregon, and Washington also agreed to pursue a new integrated style of ocean management that accounts for ecosystem interactions and multiple human uses.

This shift in thinking is embodied in the principles of ecosystem-based management, an integrated approach to management that considers the entire ecosystem, including humans. The goal of ecosystem-based management is to maintain an ecosystem in a healthy, productive, and resilient condition so that it can provide the services humans want and need, taking into account the cumulative effects and needs of different sectors. New York State has passed legislation aimed at achieving a sustainable balance among multiple uses of coastal ecosystems and the maintenance of ecological health and integrity. Washington State has created a regional public/private partnership to restore Puget Sound, with significant authority for coordinated ecosystem-based management.

These examples reflect a promising and growing movement toward comprehensive ecosystem-based management in the United States and internationally. However, efforts to date remain isolated and relatively small in scale, and U.S. ocean management has largely failed to address the cumulative effects of multiple human stressors.

Falling short

A close look at several policies central to the current system of ocean and coastal management reveals ways in which ecosystem-based management was presaged as well as reasons why these policies have fallen short of a comprehensive and coordinated ocean management system. The 1972 Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA) requires coastal states, in partnership with the federal government, to protect and preserve coastal wetlands and other ecosystems, provide healthy fishery harvests, ensure recreational use, maintain and improve water quality, and allow oil and gas development in a manner compatible with long-term conservation. Federal agencies must ensure that their activities are consistent with approved state coastal zone management plans, providing for a degree of state/federal coordination. At the state level, however, management of all of these activities is typically fragmented among different agencies, generally not well coordinated, and often reactive. In addition, the CZMA does not address important stressors on the coasts, such as the runoff of fertilizers and pesticides from inland areas that eventually make their way into the ocean.

The 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) also recognized the importance of cumulative effects. Under NEPA and related state environmental laws, agencies are required to assess cumulative effects, both direct and indirect, of proposed development projects. In addition, they must assess the cumulative effects of all other past, present, and future developments on the same resources. This is an onerous and ambiguous process, which is seldom completed, in part because cumulative effects are difficult to identify and measure. It is also a reactive process, triggered when a project is proposed, and therefore does not provide a mechanism for comprehensive planning in the marine environment.

Congress in the early 1970s also passed the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, and the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, which require the National Marine Fisheries Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to address the cumulative effects of human activities on vulnerable marine species and habitats. NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary Program is charged with conserving, protecting, and enhancing biodiversity, ecological integrity, and cultural legacy within sanctuary boundaries while allowing uses that are compatible with resource protection. The sanctuaries are explicitly managed as ecosystems, and humans are considered to be a fundamental part of those ecosystems. However, sanctuary management has often been hampered by a lack of funding and limited authority to address many important issues. Although the endangered species and marine mammal laws provide much stronger mandates for action, the single-species approach inherent in these laws has limited their use in dealing with broader-scale ecological degradation.

Existing laws may look good on paper, but in practice they have proven inadequate. Overall, U.S. ocean policy has five major shortcomings. First, it is severely fragmented and poorly matched to the scale of the problem. Second, it lacks an overarching set of guiding principles and an effective framework for coordination and decisionmaking. Third, the tools provided in the various laws lead mostly to reactive planning. Fourth, many policies lack sufficient regulatory teeth or funding to implement their mandates. Finally, scientific information and methods for judging the nature and extent of cumulative effects have been insufficient to support integrated management.

The oceans are still largely managed piecemeal, one species, sector, or issue at a time, despite the emphasis on cumulative effects and integrated management in existing laws. A multitude of agencies with very different mandates have jurisdiction over coastal and ocean activities, each acting at different spatial scales and locations. Local and state governments control most of what happens on land. States generally have authority out to three nautical miles, and federal agencies govern activities from the three-mile limit to the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) boundary, 200 nautical miles offshore. Layered on top of these boundaries are separate jurisdictions for National Marine Sanctuaries, National Estuarine Reserves, the Minerals Management Service, regional fisheries management councils, and many others. There is often no mechanism or mandate for the diverse set of agencies that manage individual sectors to communicate or coordinate their actions, despite the fact that the effects of human activities frequently extend across boundaries (for example, land-based pollutants may be carried far from shore by currents) and the activities of one sector may affect those of another (for example, proposed offshore energy facilities may affect local or regional fisheries). The result is a de facto spatial configuration of overlapping and uncoordinated rules and regulations.

Important interconnections—between human uses and the environment and across ecological and jurisdictional realms—are being ignored. The mandate for meaningful coordination among these different realms is weak at best, with no transparent process for implementing coordinated management and little authority to address effects outside of an agency’s direct jurisdiction. The increasing number and severity of dead zones are examples of this. A dead zone is an area in which coastal waters have been depleted of oxygen, and thus of marine life, because of the effects of fertilizer runoff from land. But the sources of the problem are often so distant from the coast that proving the land/coast connection and then doing something about the problem are major challenges for coastal managers.

Ocean and coastal managers are forced to react to problems as they emerge, often with limited time and resources to address them, rather than being able to plan for them within the context of all ocean uses. For example, states and local communities around the country are grappling with plans for liquefied natural gas facilities. Most have no framework for weighing the pros and cons of multiple potential sites. Instead, they are forced to react to each proposal individually, and their ability to plan ahead for future development is curtailed. Approval of an individual project requires the involvement of multiple federal, state, and local agencies; the makeup of this group varies depending on the prospective location. This reactive and variable process results in ad hoc decisionmaking, missed opportunities, stalemates, and conflicts among uses. Nationwide, similar problems are involved in the evaluation of other emerging ocean uses, such as offshore aquaculture and energy development.

The limited recovery of endangered and threatened salmon species is another example of how our current regulatory framework can fail, while also serving as an example of the potential of the ecosystem-based approach. A suite of land- and ocean-based threats, including overharvesting, habitat degradation, changing ocean temperatures, and aquaculture threaten the survival of salmon stocks on the west coast. In Puget Sound, the problem is made more complex by the interaction of salmon with their predators, resident killer whales, which are also listed as endangered. Despite huge amounts of funding and the mandates of the Endangered Species Act, salmon recovery has been hampered by poor coordination among agencies with different mandates, conflicts among users, and management approaches that have failed to account for the important influence of ecosystem interactions. In response, a novel approach was developed called the Shared Strategy for Puget Sound. Based on technical input from scientists about how multiple stressors combine to affect salmon populations, local watershed groups developed creative, feasible, salmon recovery plans for their own watersheds. Regional-scale action was also needed, so watershed-level efforts were merged with input from federal, county, and tribal governments as well as stakeholders to create a coordinated Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Plan. That plan is now being implemented by the Puget Sound Partnership, a groundbreaking public/private alliance aimed at coordinated management and recovery of not just salmon but the entire Puget Sound ecosystem.

As in Puget Sound, most areas of the ocean are now used or affected by humans in multiple ways, yet understanding how those various activities and stresses interact to affect marine ecosystems has proven difficult. Science has lagged behind policies aimed at addressing cumulative effects, leaving managers with few tools to weigh the relative importance and combined effects of a multitude of threats. In some cases, the stressors act synergistically, so that the combination of threats is worse than just the sum of their independent effects. Examples abound, such as when polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon pollutants combine with increases in ultraviolet radiation to increase the mortality of some marine invertebrates. Recent work suggests that these synergistic effects are common, especially as more activities are undertaken in a particular place. The science of multiple stressors is still in its infancy, and only recently has a framework existed for mapping and quantifying the impacts of multiple human activities on a common scale. This scientific gap is a final critical limitation on active and comprehensive management of the marine environment.

Toward ocean zoning

Advocates for changing U.S. ocean policy are increasingly calling for comprehensive ocean zoning, a form of ecosystem-based management in which zones are designated for different uses in order to separate incompatible activities and reduce conflicts, protect vulnerable ecosystems from potential stressors, and plan for future uses. Zoning is already in the planning stages in a variety of places.

Creating a comprehensive, national, ecosystem-based, ocean zoning policy could address many of the ubiquitous problems with current policy by providing a set of overarching guiding principles and a standardized mechanism for the planning of ocean uses that takes into account cumulative effects. In order to be successful, the policy must mandate and streamline interagency coordination and integrated decisionmaking. It should also provide for public accountability and effective stakeholder engagement. Finally, it should be supported by scientific tools and information that allow participants in the process to understand where and why serious cumulative effects occur and how best to address them.

An integrated management approach would be a major shift in ocean policy. Managers will need not only a new governance framework but also new tools for prioritizing and coordinating management actions and measuring success. They must be able to:

- Understand the spatial distribution of multiple human activities and the direct and indirect stresses on the ecosystem associated with those activities

- Assess cumulative effects of multiple current and future activities, both inside and out of their jurisdictions, that affect target ecosystems and resources in the management area

- Identify sets of interacting or overlapping activities that suggest where and when coordination between agencies is critical

- Prioritize the most important threats to address and/or places to invest limited resources

- Effectively monitor management performance and changing threats over time

Given the differences among the stressors—in their effects, intensity, and scale—comparing them with a common metric or combining them into a measure of cumulative impact in order to meet these needs has been difficult. Managers have lacked comprehensive data and a systematic framework for measuring cumulative effects, effectively making it impossible for them to implement ecosystem-based management or comprehensive ecosystem-based ocean zoning. Thanks to a new tool developed by a diverse group of scientists and described below, managers are now able to assess, visualize, and monitor cumulative effects. This tool is already being used to address the needs listed above and to guide the implementation of ecosystem-based management in several places. The resulting maps of cumulative human impact produced by the process show an over-taxed ocean, reinforcing the urgent need for careful zoning of multiple uses.

An assessment tool

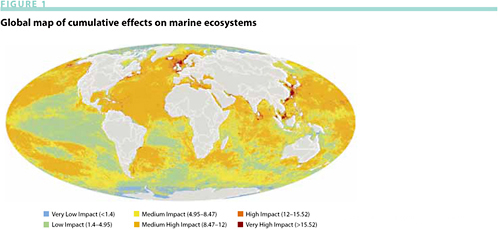

The first application of this framework for quantifying and mapping cumulative effects evaluated the state of the oceans at a global scale. Maps of 17 different human activities, from pollution to fishing to climate change, were overlaid and combined into a cumulative impact index. The results dramatically contradict the common impression that much of the world’s ocean is too vast and remote to be heavily affected by humans (figure 1). As much as 41% of the ocean has been heavily influenced by human activity (the orange to red areas on the map), less than 4% is relatively unaffected (the blue areas), and no single square mile is unaffected by the 17 activities mapped. In coastal areas, no fewer than 9 and as many as 14 of the 17 activities co-occur in every single square mile. The consequences of this heavy use may be missed if human activities are evaluated and managed in isolation from one another, as they typically have been in the United States and elsewhere. The stunning ubiquity of multiple effects highlights the challenges and opportunities facing the United States in trying to achieve sustainable use and long-term protection of our coasts and oceans.

The global map makes visible for the first time the overall impact that humans have had on the oceans. More important, the framework used to create it can help managers move beyond the current ad hoc decisionmaking process to assess the effects of multiple sectors simultaneously and to consider their separate and cumulative effects, filling a key scientific gap. The approach makes the land/sea connection explicit, linking the often segregated management concerns of these two realms. It can be applied to a wide range of management issues at any scale. Local and regional management have the most to gain by designing tailored analyses using fine-scale data on relevant activities and detailed habitat maps. Such analyses have recently been completed for the Northwest Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument and the California Current Large Marine Ecosystem, which stretches from the U.S.-Canada border to Mexico. Armed with this tool, policymakers and managers can more easily make complex decisions about how best to design comprehensive spatial management plans that protect vulnerable ecosystems, separate incompatible uses, minimize harmful cumulative effects, and ultimately ensure the greatest overall benefits from marine ecosystem goods and services.

Policy recommendations

Three key recommendations emerge as priorities from this work. First, systematic, repeatable integration of data on multiple combined effects provides a way to take the pulse of ocean conditions over time and evaluate ocean restoration and protection plans, as well as proposed development. Policymakers should support efforts by scientists and agencies to develop robust ways to collect these critical data.

The framework developed to map human effects globally is beginning to play an important role in cumulative-impact assessment and the implementation of ecosystem-based management and ocean zoning. This approach integrates information about a wide variety of human activities and ecosystem types into a single, comparable, and updatable impact index. This index is ecologically grounded in that it accounts for the variable responses of different ecosystems to the same activity (for example, coral reefs are more sensitive to fertilizer runoff than are kelp forests). The intensity of each activity is assessed in each square mile of ocean on a common scale and then weighted by the vulnerability of the ecosystems in that location to each activity. Weighted scores are summed and displayed in a map of cumulative effects.

With this information, managers can answer questions such as, where are areas of high and low cumulative impact? What are the most important threats to marine systems? And what are the most important data gaps that must be addressed to implement effective integrated management of coastal and marine ecosystems? They can also identify areas in which multiple, potentially incompatible activities overlap, critical information for spatial planning. For example, restoring oyster reefs for fisheries production may be ineffective if nearby activities such as farming and urban development result in pollution that impairs the fishery. Further, managers can use the framework to evaluate cumulative effects under alternative management or policy scenarios, such as the placement of new infrastructure (for example, wind or wave energy farms) or the restriction of particular activities (for example, certain kinds of fishing practices).

This approach highlights important threats to the viability of ocean resources, a key aspect of NOAA’s framework for assessing the health of marine species’ populations. In the future, it might also inform a similar framework for monitoring the condition of coastal and ocean ecosystems. In particular, this work could contribute to the development of a national report card on ocean health to monitor the condition of our oceans and highlight what is needed to sustain the goods and services they provide. NOAA’s developing ecosystem approach to management is fundamentally adaptive and therefore will depend critically on monitoring. This tool is a valuable contribution to such efforts, providing a benchmark for future assessments of ocean conditions and a simple new way to evaluate alternative management strategies.

The second key policy recommendation is that, because of the ubiquity and multitude of human uses of the ocean, cumulative effects on marine ecosystems within the U.S. EEZ can and must be addressed through comprehensive marine spatial planning. Implementing such an effort will require new policies that support ocean zoning and coordinated regional planning and management under an overarching set of ecosystem-based guiding principles.

The vast extent, patchwork pattern, and intensity of stressors on the oceans highlight the critical need for integrated planning of human activities in the coastal and marine environments. However, this patchwork pattern also represents an opportunity, because small changes in the intensity and/or location of different uses through comprehensive ocean zoning can dramatically reduce cumulative effects.

Understanding potential tradeoffs among diverse social and ecological objectives is a key principle of ecosystem-based management and will be critical to effective ocean zoning. Quantification and mapping of cumulative effects can be used to explore alternative management scenarios that seek to balance tradeoffs. By assessing how cumulative effects change as particular human activities are added, removed, or relocated within the management area, managers, policymakers, and stakeholders can compare the potential costs and benefits of different decisions. Decisionmaking by the National Marine Sanctuaries, coastal states, and regional ecosystem initiatives could all potentially benefit from revealing areas of overlap, conflict, and incompatibility among human activities. In the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, this approach is already being used to help guide decisions on where different activities should be allowed in this highly sensitive ecosystem.

Other spatial management approaches, particularly marine protected areas (MPAs), can also benefit from this framework and tool. Most MPA regulations currently restrict only fishing, but the widespread overlap of multiple stressors suggests that for MPAs to be successful, managers must either expand the list of activities that are excluded from MPAs, locate them carefully to avoid negative effects from other human activities, or implement complementary regulations to limit the impact of other activities on MPAs. Comprehensive assessments and mapping of cumulative effects can be used at local or regional levels to highlight gaps in protection, select areas to protect, and help locate MPAs where their beneficial effects will be maximized. For example, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority of Australia embedded its large network of MPAs within other zoning and regulations to help address the many threats to coral reef ecosystems not mitigated by protection in MPAs.

The transition to comprehensive ocean zoning will not happen overnight. The governance transition, coordination with states and neighboring countries, engagement of diverse stakeholder groups, and scientific data collection and integration, among other challenges, will all take significant time, effort, and political will. These efforts would be galvanized by the passage of a U.S. ocean policy act, one that cements the country’s commitment to protecting ocean resources, just as the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts have done for air and fresh water. In addition, continued strengthening and funding of the CZMA would support states’ efforts to reduce the impact of coastal and upstream land use on coastal water quality and protect vulnerable ecosystems from overuse and degradation. Lawmakers could also increase the authority of the National Marine Sanctuary Program as a system of protected regions in which multiple human uses are already being managed. Finally, legislation to codify NOAA and support and increase its efforts to understand and manage marine ecosystems in an integrated way is urgently needed.

The third key policy recommendation is that protection of the few remaining relatively pristine ecosystems in U.S. waters should be a top priority. U.S. waters harbor important intact ecosystems that are currently beyond the reach of most human activities. Unfortunately, less than 2% of the U.S. EEZ is relatively unaffected. These areas are essentially national ocean wilderness areas, offering rich opportunities to understand how healthy systems work and important baselines to inform the restoration of those that have been degraded. These areas deserve immediate protection so that they can be maintained in a healthy condition for the foreseeable future. The fact that these areas are essentially unaffected by human activity means that the cost of protecting them in terms of lost productivity or suspended economic activity is minimal. The opportunity cost is small and the returns likely very large, making a strong case for action. If the nation waits to create robust marine protected areas to permanently conserve these intact places, it risks their degradation and a lost opportunity to protect the small percentage of marine systems that remains intact.