Imagining Deep Time

An exhibit at the National Academy of Sciences Building, Washington, DC

“Geohistory is the immensely long and complex history of the earth, including the life on its surface (biohistory), as distinct from the extremely brief recent history that can be based on human records.”

—Martin J.S. Rudwick, science historian

From a human perspective, mountain ranges seem unchanging and permanent; yet, in the context of geological time, such landscapes are merely fleeting. Their change occurs on a scale far beyond human experience. Whereas we measure time in terms of years, days, and minutes, geological change occurs within the scale of deep time, the gradual movement of evolutionary change.

The concept of deep time was introduced in the 18th century, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that John McPhee coined the term “deep time” in his book Basin and Range. The Imagining Deep Time exhibition, which contains 18 works by 15 artists, looks at the human implications of deep time through the lens of artists who bring together rational and intuitive thinking. The featured artists use a wide range of styles and media, including sound, photography, painting, printmaking, and sculptures made of everyday materials such as mirrors, LED lights, motors, and gears. The exhibition explores the role of the artist in helping us imagine a concept outside the realm of human experience.

Artists featured are Chul Hyun Ahn, Alfredo Arreguín, Diane Burko, Alison Carey, Terry Falke, Arthur Ganson, Sharon Harper, Mark Klett, Rosalie Lang, David Maisel, the artistic team Semiconductor, Rachel Sussman, Jonathon Wells, and Byron Wolfe.

Imagining Deep Time is on exhibit at the National Academy of Sciences Building, 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W., Washington, DC, August 28, 2014, through January 15, 2015.

—Alana Quinn and JD Talasek

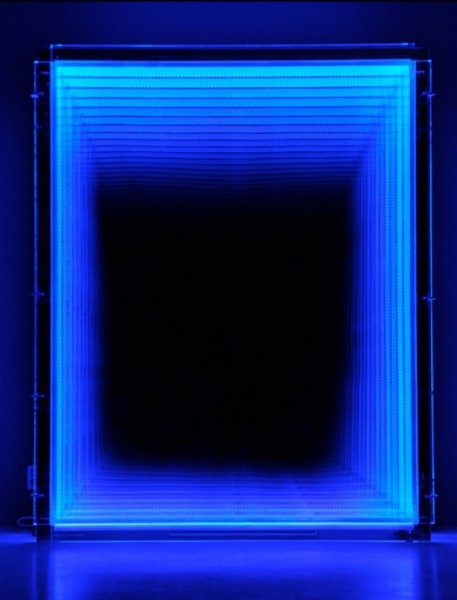

Chul Hyun Ahn Void. Cast acrylic, LED lights, hardware, mirrors. 90 x 71½ x 12¼ inches. 2011

Chul Hyun Ahn Void. Cast acrylic, LED lights, hardware, mirrors. 90 x 71½ x 12¼ inches. 2011

Baltimore-based artist Chul Hyun Ahn uses repetition to evoke infinite cycles. His work recalls that of minimalists such as Dan Flavin and Donald Judd who incorporated the use of everyday materials to create experiential spaces.

Terry Falke Cyclists Inspecting Ancient Petroglyphs, Utah. Digital chromogenic print. 30 x 40 inches. 1998

Terry Falke Cyclists Inspecting Ancient Petroglyphs, Utah. Digital chromogenic print. 30 x 40 inches. 1998

A cyclist points at marks left on the earth by humans–petroglyphs of human figures (whose heads resemble the helmets worn by the cyclists) and bullet holes. The line of the road suggests an added human-made stratum reminding us that, although humans’ presence in the continuum of deep time is small, we have left our mark.

Alfredo Arreguín The Age of Reptiles. Oil on canvas. 60 x 48 inches. 2012

Alfredo Arreguín The Age of Reptiles. Oil on canvas. 60 x 48 inches. 2012

The patterns in Alfredo Arreguín’s paintings are based on pre-Aztec images, Mexican tiles, and geometric patterns. His brilliantly colored canvas combines childhood memories of Mexican culture and landscapes with imagery inspired by animals that are only known to have existed through scientific research. Arreguín invites us to imagine how our environment has evolved and how we are influenced by cultural experience.

David Maisel Black Maps (Bingham Canyon, UT I). Archival pigment print. 29 x 29 inches. 1988

David Maisel Black Maps (Bingham Canyon, UT I). Archival pigment print. 29 x 29 inches. 1988

According to the artist, the title Black Maps, which comes from a poem by Mark Strand, refers to the notion that although these images document the facts of these sites, they are essentially unreadable, much as a map that is black would be. As Strand writes, “Nothing will tell you where you are/Each moment is a place you’ve never been.” David Maisel considers these images not only documents of blighted sites, but also poetic renderings that reflect the human psyche that made them.

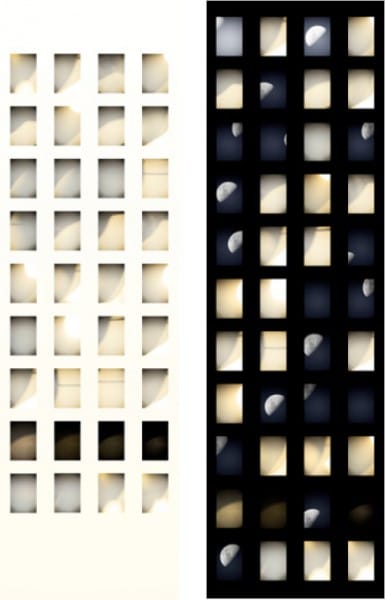

Sharon Harper

Sharon Harper

Left: Sun/Moon (Trying to See through a Telescope) 2010 May 27 10:48:35 AM.2010 May 27 11:08:34 AM

Right: Sun/Moon (Trying to See through a Telescope) 2010 May 27 10:48:35 AM.2010 May 27 11:08:34 AM 2010 Jun 19 8:16:30 PM.2010 Jun 19 8:23:40 PM, No. 2 2010

Ultrachrome print on Canson Rag Photographique paper. 58⅛ x 17 inches each. 2010

One way we experience time is through cycles such as the phases of the sun and the moon or through the passing of seasons. Yet the act of representing these cycles is different than actually experiencing them. Sharon Harper’s Sun/Moon series considers the act of “seeing” as mediated through both a telescope and a digital camera.

Rosalie Lang Inner Life. Oil on canvas. 20 x 22 inches. 2009

Rosalie Lang Inner Life. Oil on canvas. 20 x 22 inches. 2009

Rosalie Lang’s paintings draw inspiration from the aesthetic of rocks photographed along the Pescadero, CA coast. She writes, “I don’t know a rock until I paint it,” underscoring the importance of mark-making in observation and learning. The realism of Lang’s paintings of rock surfaces, combined with the absence of horizon or other cues to scale, may cause viewers’ perception to oscillate between reality and abstraction.

Jonathon Wells Boston Basin. Digital inkjet print. 28½ x 78 inches. Photographed 2004, composited 2005

Jonathon Wells Boston Basin. Digital inkjet print. 28½ x 78 inches. Photographed 2004, composited 2005

This work depicts a 16-mile-wide by four-and-a-half-mile-deep view of Boston Basin looking west toward downtown as if the viewer were positioned in the harbor. The large city seems miniscule in comparison to what lies beneath. The Geologic Map of Massachusetts (1983) by National Academy of Sciences member E-an Zen and others provided the basis for constructing the image.

Diane Burko Columbia Triptych II Vertical Aerial 1981–1999, A, B, C after Austin Post and Tad Pfeffer. Oil on canvas. 76 x 36 inches, each canvas. 2010

Diane Burko Columbia Triptych II Vertical Aerial 1981–1999, A, B, C after Austin Post and Tad Pfeffer. Oil on canvas. 76 x 36 inches, each canvas. 2010

Diane Burko’s inspiration for these paintings is a montage of five aerial photographs of the lower reach of the Columbia Glacier, Alaska, taken on October 2, 1998. Superimposed on the montage are plots of selected terminus positions from 1981 to 1999. Combining the aesthetics of photography, scientific notations, and landscape painting, Burko asks us to consider the role of art in communicating about climate change.

Alison Carey Stethacanthus, Pennsylvanian Period, 280–310 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

Alison Carey Stethacanthus, Pennsylvanian Period, 280–310 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

Criptolithus & Eumorphocystis, Ordovician Period, 440–500 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

Criptolithus & Eumorphocystis, Ordovician Period, 440–500 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

Crinoids, Mississippian Period, 310–350 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

Crinoids, Mississippian Period, 310–350 mya. Silver gelatin on black glass. 9 x 23 inches. 2005

These photographs come from Alison Carey’s series Organic Remains of a Former World, representing ancient marine environments from each Paleozoic era. Carey built clay models of extinct vertebrates and invertebrates, submerged them in multiple aquariums, and photographed the constructed tableaus. She used scientific data and illustrations of fossils to inform her ideas.

Rachel Sussman Dead Huon Pine adjacent to living population segment #1211-3509 (10,500 years old, Mount Read, Tasmania) Archival pigment print. 44 x 54 inches. 2011

Rachel Sussman Dead Huon Pine adjacent to living population segment #1211-3509 (10,500 years old, Mount Read, Tasmania) Archival pigment print. 44 x 54 inches. 2011

This photograph depicts Lagarostrobos franklinii, a conifer species native to Tasmania, killed by fire. This scene is bordered by living trees with an extraordinary legacy. The age of the stand was determined by dating pollen from Lake Johnston which matched the genetic make-up of the living trees and carbon-dates to 10,500 years old. The photograph is from Sussman’s series The Oldest Living Things in the World, the result of her collaboration with scientists to identify and photograph organisms that are at least 2,000 years old.