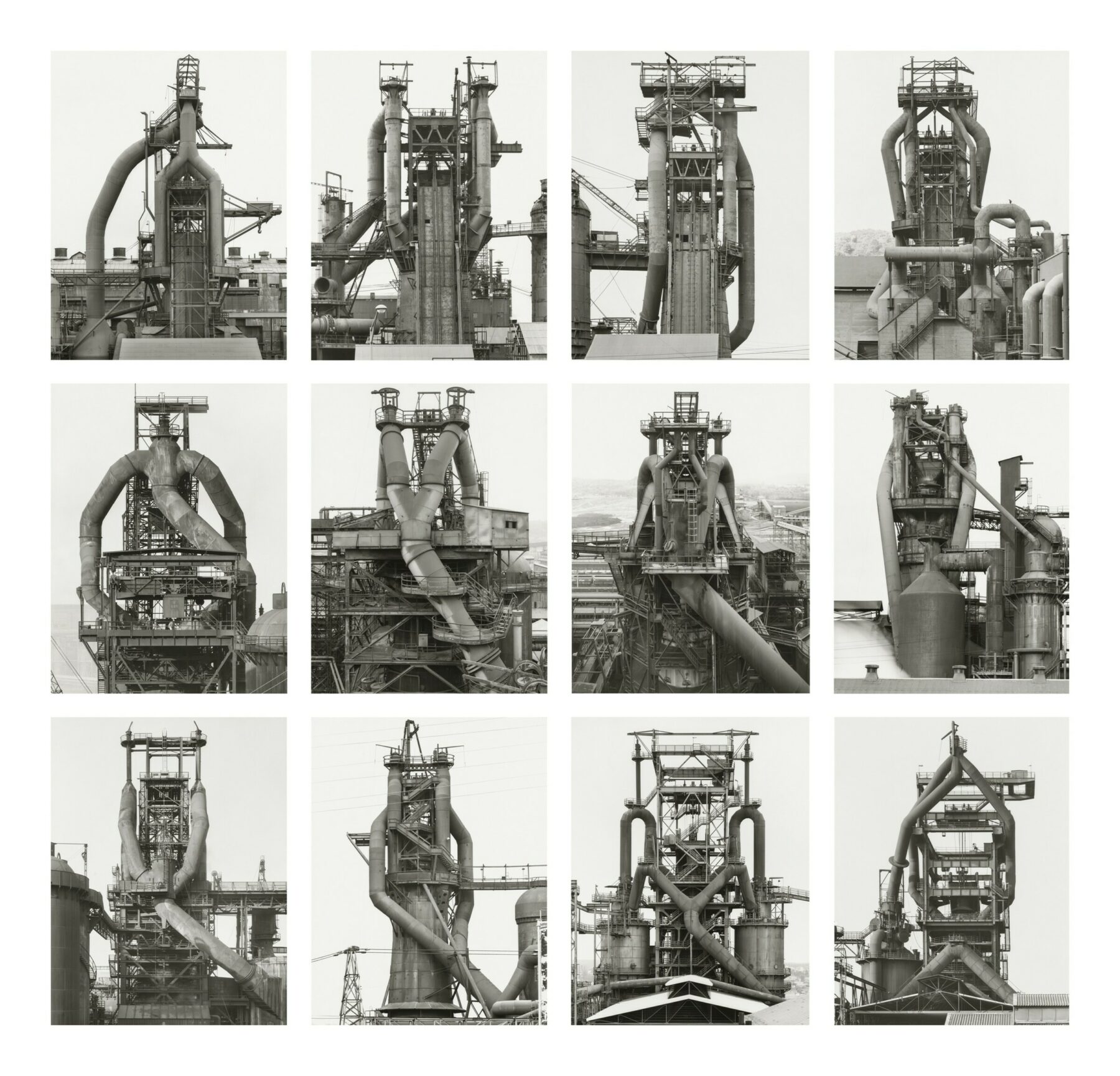

Natural Historians of the Industrial Landscape

The “anti-Ansel Adams” photography of Hilla and Bernd Becher.

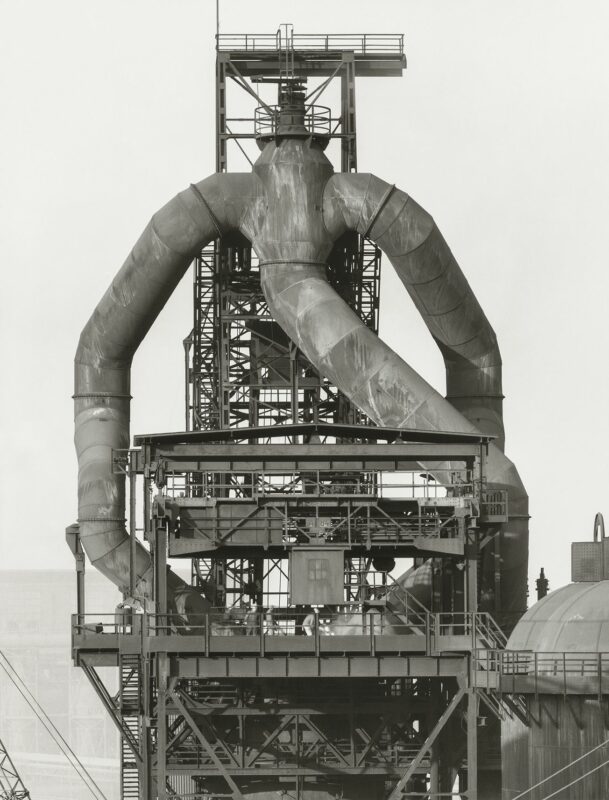

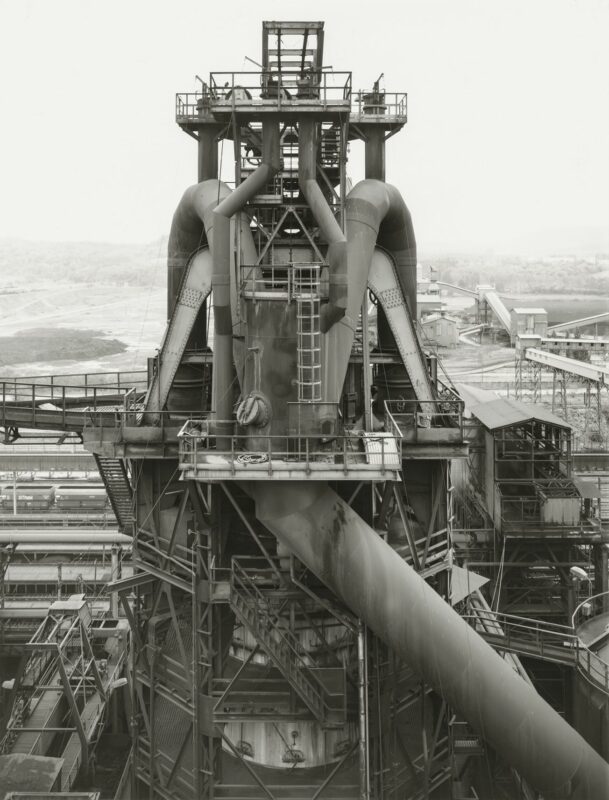

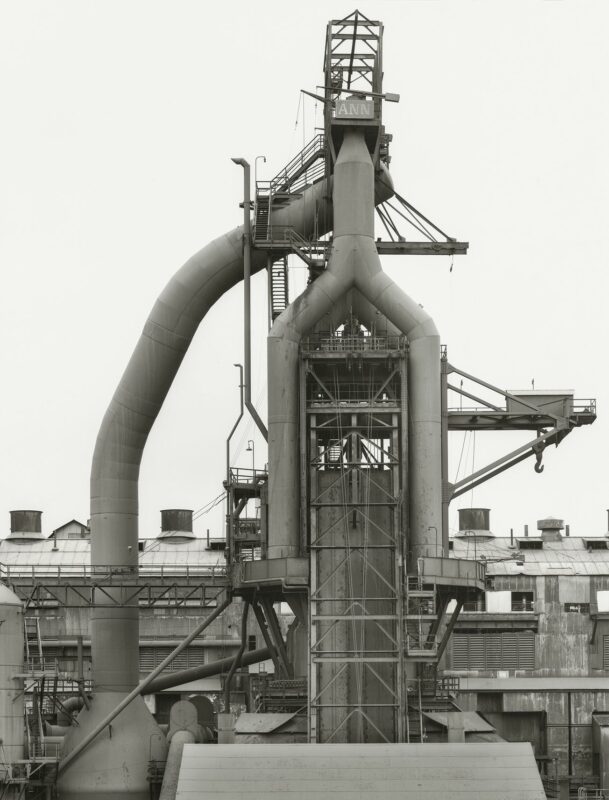

Hilla and Bernd Becher were a collaborative duo of German conceptual art photographers who profoundly changed the way artists saw the post-World War II landscape. For more than 40 years, they studied the postindustrial architecture of Western Europe, later moving on to that of the United States’ Rust Belt. They made images of these utilitarian buildings very systematically—with large-format cameras that revealed exquisite detail in black and white.

They composed their images so that the buildings—famously water towers, gas tanks, grain elevators, and the like—were isolated against the sky, often using ladders to gain a better perspective and shooting on overcast days in early morning in spring or fall. They then gathered these images into typologies—systematic classifications according to common characteristics—in this case, industrial functions. The works were typically displayed in grids of multiple images of six, nine, or more, emphasizing the relationship between form and function. Gazing at these displays, viewers find the rhythms, patterns, and nuances as the structures reveal their variations within the theme.

This work, which became a profound meditation on the end of the industrial age, grew out of the couple’s early life experiences. Hilla (1934–2015) learned photography from her mother, and later apprenticed as a commercial photographer. Bernd (1931–2007) grew up in a town located near a blast furnace, where many people worked in steel and mining. Bernd Becher and Hilla Wobeser met at an ad agency while attending art school at Dusseldorf Academy. At the time, the academy did not offer photography courses, but Hilla convinced her professors to let her order equipment. In 1957, Bernd returned to his home to draw the ironworks, but when he found it to be under demolition, he took snapshots to use as the basis for his sketches. The Bechers began collaborating and were married in 1961.

Gazing at these photographs, typically displayed in grids, viewers find the rhythms, patterns, and nuances as the structures reveal their variations within the theme.

Though the Bechers’ work was groundbreaking, it drew on a rich prewar art movement called Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. In the 1920s, the movement’s followers, rejecting expressionism, embraced unsentimental representation of the world.

The movement was epitomized by the work of the German photographer August Sander. Sander, who worked for a mine before learning to use a camera, set out to take photos of workers from all walks of life, creating an ambitious sociological collective portrait called People of the Twentieth Century.

Another New Objectivist, Karl Blossfeldt, used special homemade cameras to dramatically magnify plants. His images, published as Art Forms in Nature, showed buds at the apex of stems, isolated on a blank contrasting background.

Critics have long cited the relationship between Blossfeldt and the Bechers, with Sean O’Hagan, the photography critic for the British newspaper The Guardian, observing that “the Bechers approached photography the way a botanist might approach the cataloguing of flora and fauna.”

KARL BLOSSFELDT (German, 1865–1932)

Cucurbita, 1928, Gelatin silver print, 25.9 × 20.3 cm (10 3/16 × 8 in.), 84.XM.142.10. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Karl Blossfeldt Archiv / Ann and Jürgen Wilde / Cologne, Germany / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

In this vein, Bernd Becher described their work as a kind of visual taxonomy: “We want to offer the audience a point of view, or rather a grammar, to understand and compare different structures. Through photography, we try to arrange these shapes and render them comparable. To do so, the objects must be isolated from their context and freed from all association.”

It may be that the Bechers saw themselves as natural historians of the industrial landscape. In an interview with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Hilla spoke about the obsession that characterized her work: “If somebody is interested in cockroaches or whatever strange things and you get deeper and deeper and it gets more and more interesting.… It’s about your own understanding and your own pleasure.… If you start something, you don’t know how far you get.”

“If somebody is interested in cockroaches or whatever strange things and you get deeper and deeper it gets more and more interesting…. It’s about your own understanding and your own pleasure…. If you start something, you don’t know how far you get.”

Though the buildings they photographed were historic, the Becher’s did not prioritize history in their works—instead emphasizing form, calling their subjects “Grundformen,” or “Basic Forms,” and later “Anonymous Sculptures.” They were fascinated by basic forms that slipped free of their identity, so that an Italian gasometer (a large storage tank) was no longer specifically Italian. Bernd once said, “There is a form of architecture that consists in essence of apparatus, that has nothing to do with design, and nothing to do with architecture either. They are engineering constructions with their own aesthetic.”

Still, for all its formal rigor, detachment, and aesthetic beauty, their project is tinged with melancholy. In his essay The Photographic Comportment of Bernd and Hilla Becher, the art historian Blake Stimson writes that the Bechers’ industrial subjects “have aged and are now empty of all but memory of the ambition they once housed.”

The Bechers’ influence in the art world began in the 1970s, notably when their work was included in an exhibit called New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. The curator, William Jenkins, conceived of the exhibition with the help of the American photographer Joe Deal as a snapshot of a group of photographers making kind of “anti-Ansel Adams” images of the landscapes “all around us” rather than “magnificent and romantically-oriented” images. The Bechers were included on a tip from the Sonnabend Gallery, based in New York and known for showcasing American and European contemporary artists. Jenkins admits he’s still “kind of mystified” by the way the exhibition influences landscape photography to this day.

Still, for its formal rigor, detachment, and aesthetic beauty, their project is tinged with melancholy.

Though the Bechers influenced artists such as Ed Ruscha and sculptor Carl Andre, perhaps their most pronounced legacy was among their students, who include Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff, and Thomas Struth— now known as the “Becher School.” Though these artists continue the tradition of using an objective style, they see the architecture itself quite differently from their teachers. Struth’s most famous series of photographs of the interiors of museums busy with visitors makes viewers aware of the act of looking itself. Candida Höfer’s series of cultural institutions’ interiors is similarly a collection of collections. Breaking with his study of architecture for a series of very-large-scale head-and-shoulders portraits, Ruff asks his subjects to remain expressionless, making images that reveal physical attributes such as eyelashes and pores in excruciating detail, but withhold signs of character or personality.

AUGUST SANDER (German, 1876–1964)

Pastry Cook, 1928

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; ARS, New York.

Gursky, the most well-known of the group, has become synonymous with his massive photographic images that include stock exchange floors, supermarket shelves, and endless rows of windows of apartment buildings. Unlike the Bechers, Gursky does not work in series. He has embraced digital technologies that allow him to stitch together multiple images to obtain his feats of scale. And he employs an elevated perspective that gives viewers a sense of omniscience.

Charlotte Cotton observes, “The most prominent and probably most frequently used style of photography since the 1990s has been the deadpan aesthetic: a dispassionate, patient, keenly sharp version of photography.”

In looking at the legacy of the Bechers among photographers and at large, the independent curator and writer Charlotte Cotton observes, “The most prominent and probably most frequently used style of photography since the 1990s has been the deadpan aesthetic: a dispassionate, patient, keenly sharp version of photography.”

To quote Hilla again, “If you start something, you don’t know how far you get.” Indeed.

BERND AND HILLA BECHER, Blast Furnaces, 1970–1984; © Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher, represented by Max Becher; courtesy Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – Bernd and Hilla Becher Archive, Cologne.