Field Notes on Moving Focused Research Organizations Forward

Four years ago, we founded a new kind of scientific organization to build fundamental technologies and accelerate discovery. Almost a dozen launches later, we have an idea of what works—and what doesn’t.

Over the last two decades, the cost of sequencing a million DNA base pairs fell from over $5,000 to less than a penny. That cost reduction enabled research across precision medicine, high-throughput small-molecule screening, species identification from air and water samples, atlases of gene activity and protein content for diverse cell types, virtual cell models, and many other applications, including many totally unanticipated by earlier DNA sequencing technologists. Consider what scientists wouldn’t be doing as well or at all without that fundamental capacity.

Low-cost sequencing came about via a fortuitous mixture of the government-funded Human Genome Project, academic discovery, and industry innovation. However, megaprojects like the Human Genome Project or the particle accelerators at CERN, as important and empowering as they have been, are rare one-offs. Many smaller-scale, critical gaps in capability remain, but the scientific enterprise is not set up to systematically identify, let alone bridge, these gaps.

Funding for academic research is less stable than ever, and, generally speaking, academic science institutions don’t provide the engineering teamwork needed to produce the platforms, datasets, or tools that might fill these gaps. Likewise, venture capital and industry are poorly incentivized to produce research-enabling tools that are also broadly accessible. What’s needed is a way to stand up dedicated institutions to produce such public goods.

Certainly many inspiring, important ways to foster innovation have arisen in recent decades. Government-funded and endowment-supported research centers of excellence remain indispensable and have produced many crucial research tools. Yet, even when they are well resourced, such centers are not ideally equipped to quickly spin up the sort of interdisciplinary teams with sustained engineering support that are needed to tackle newly recognized capabilities gaps.

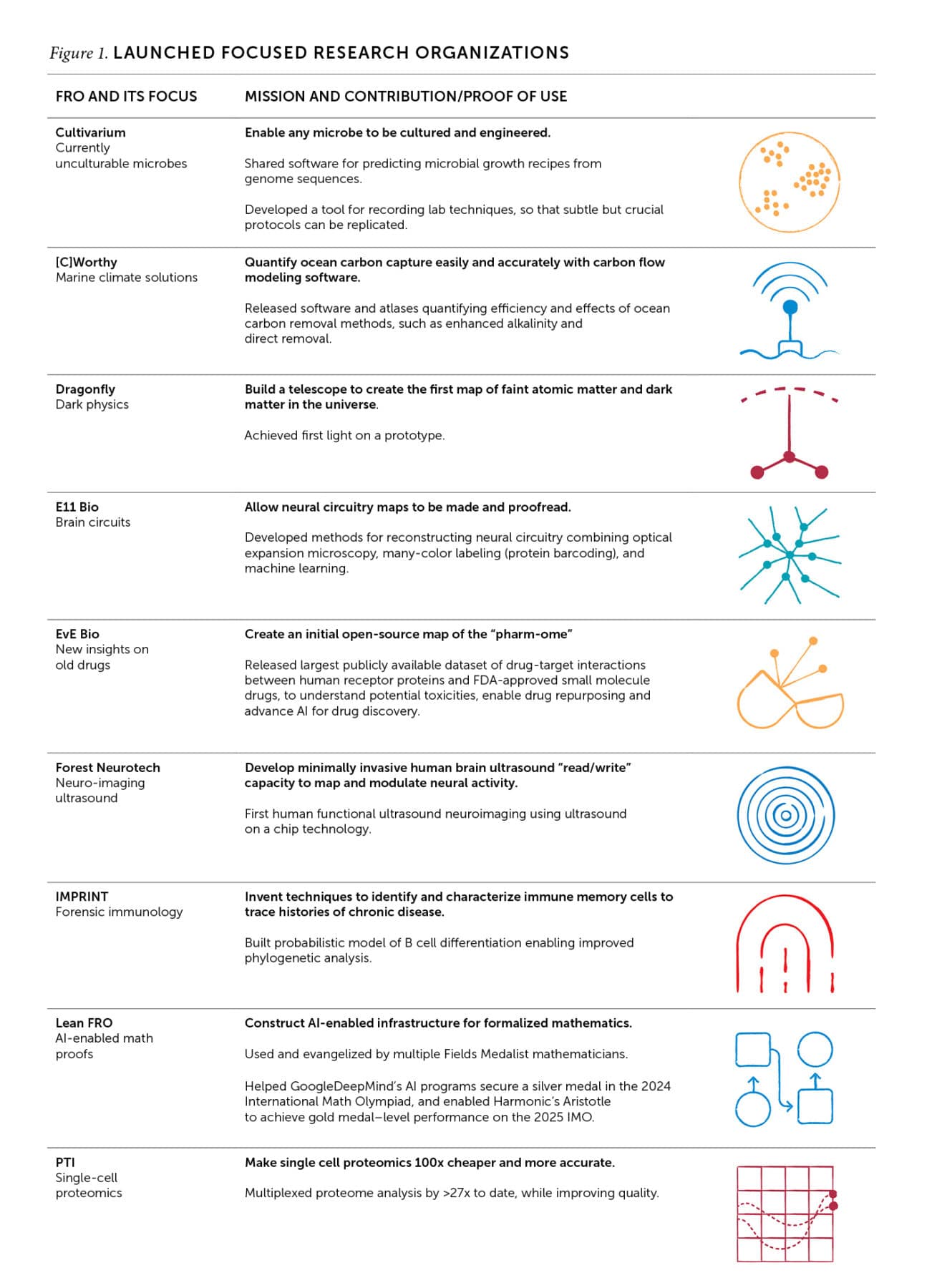

In 2021, two of us (Marblestone and Gamick) founded the nonprofit Convergent Research to support mid-scale engineering projects that create tools scientists and technologists can use to advance their fields. We structure these projects as nonprofit start-ups and call them Focused Research Organizations (FROs). Each is tasked with breaking through or routing around a particular bottleneck in the research enterprise. For instance, E11 Bio is building an imaging system to shrink the cost of mapping brain wiring by a hundredfold. Another Convergent FRO, the Parallel Squared Technology Institute, recently described methods to increase by nearly 30-fold the number of samples that can be run through proteomics analyses in parallel.

When launching Convergent’s first FROs, we looked for projects that met certain characteristics. They had to produce resources that could enable high-impact experiments and research questions. And they needed to do so with finite inputs: an integrated team of 10–30 full-time employees, an investment of $20–50 million, and a time frame of three to seven years. We also looked across a diversity of scientific disciplines. In addition to neuroscience and proteomics, we’ve found projects in fields like immunology, synthetic biology, pharmacology, mathematics, and oceanic carbon sequestration.

After launch, each FRO begins to work through a series of quantifiable technical milestones. FROs are also tasked to efficiently disseminate the resources they produce. Some supply open-source data or reagents, others partner with existing institutions, and still others plan to spin out start-ups or nonprofits. From the start, we urge FROs to plan how they will transition and whether they will move their tools and technologies into a long-standing home along the lines of a “.org” (perpetual foundation), “.gov” (state-supported public good), or “.com” (commercial entity)—or something in between—based on whatever sort of organization can expand the technology’s use.

Venture capital and industry are poorly incentivized to produce research-enabling tools that are also broadly accessible. What’s needed is a way to stand up dedicated institutions to produce such public goods.

Four years in, we are seeing the first wave of FRO transitions, and we have learned a great deal from the FROs we’ve launched ourselves, similar projects we’ve helped others establish, and others’ efforts in building scientific organizations. Here we describe how our vision has evolved, what we learned about concerns that never materialized, and how we managed to mitigate those that did.

Finding FRO-shaped problems

One of the earliest and most obvious challenges of working in the FRO space is figuring out precisely where this new organizational format should be used. In our view, FROs should not replace any part of the existing scientific ecosystem. Indeed, we believe that most scientific endeavors don’t need to be done via an FRO. Existing scientific organizations—such as company R&D departments, university labs, start-ups, or governmental institutions—all have types of scientific work they’re particularly good at. Consequently, we look for bottlenecks none of these traditional organizations could address.

One source of ideas is reaching out to the research community. Working with the United Kingdom’s Advanced Research + Invention Agency (ARIA) we released an open call for FROs aligned with ARIA’s “opportunity spaces,” such as math for safe AI, scalable neural interfaces, and programmable plants. We reviewed nearly 100 applications for this incubation program. Of them, five founding teams are now taking part in a six-month residency for developing FRO concepts ranging from environmental data-sharing to hardware-enabled governance systems for AI.

We’ve also developed road-mapping approaches to identify and track core missing capabilities in select scientific fields, often hiring fellows and supporting white papers or workshops to imagine how FROs (or other formats) could fill these needs. In the process, we’ve begun to crystallize a philosophy for how to look across science for gaps that can be bridged by the FRO approach.

Consider the “tech tree,” an approach used in strategy games to visually represent how players can leverage simple capacities into complex inventions, with branches showing how some capacities build upon each other before spreading out into multifarious inventions and applications. In the real world, we often notice the tips of these branches that bear fruit: diverse commodities, powerful devices for computing and connection, innovative medicines, life-preserving infrastructure that maintains clean water and air. With a tech tree, we can trace the existence of a particular cluster of inventions back to the branch that produced it and trace that branch back to the trunk of the tree, where an especially fundamental capability nourished it.

Would working in an untested sort of research organization have appeal compared to the potential for decades of job security in academia or fortune-making equity in industry?

We hypothesize that FROs can help stunted parts of the trunk begin to produce thriving, branching limbs of further technological progress. But to see where a stunted trunk can sprout, one must dare to hope and think beyond the day-to-day life of most scientists, or even the day-to-day life of most people reading this. We have to ask: What’s missing, and why?

Posing the question alone is not enough; to actually move forward, you need tractable answers. And, as we have found, without a credible solicitation for a tangible opportunity, it often makes no sense for scientists to put time into sketching out FRO-shaped ideas. After all, there are experiments to do and papers to write. To elicit FRO ideas, something must perturb the lab-bound, conference-going, article-publishing researcher into a mindset that can nourish ambitious FRO-shaped dreams—and the concrete technical plans to realize them. So we set out to map the stunted points of the tech tree systematically, using structured queries to scientists alongside parallel conversations with funders. Innovation scholars Michael Nielsen and Kanjun Qiu referred to our work as eliciting “intellectual dark matter” (i.e., ideas that would not otherwise come to light).

Specifically, we deploy what Nielsen and Qiu call a detector-and-predictor model and adapt it for FROs. This process helps us map bottlenecks across fields and hunt out ideas for research-enabling projects; anticipate how resulting technologies could be disseminated; and filter away those projects that can be accomplished within traditional structures. This process has produced what we believe is a strong set of FRO-shaped ideas to create critical scientific infrastructure that other researchers and technology developers can use, reuse, and build on.

Part of our thesis holds that, of the many capability gaps FROs could bridge, some have more potential than others. We understand a key part of our job to be helping the research community focus on capability gaps closest to the “trunk” of the tech tree. For example, we had a hunch that filling infrastructure gaps in mathematics would have high leverage, even though much work in math needs only a pen and paper. After all, mathematics underlies so much scientific work. Early on in our road mapping, we identified the Lean Theorem Prover as a useful software platform for mathematicians to build trust in one another’s proofs. As it turned out, the formalization offered by Lean has become key for AI support to prove theorems, and even has promise for automating some meaningful mathematical work. More concretely, enabling AI assistance in proving mathematical theorems about software itself could help make software more secure. Our intuition about looking for an FRO-shaped problem in math thus seems to be sprouting branches and bearing fruit.

It turns out that there are many FRO-shaped opportunities in “trunk” regions of the sciences. Some are developing tools to enable experiments; others are building rigorous, accessible datasets. Both approaches could nourish computational efforts that can dramatically accelerate scientific progress. We see the work that FROs do as building toward data-sharing advocate John Wilbanks’s vision of “new ways of performing science with data at a massive scale [that] will look quite different from the ‘one lab, one hypothesis’ experiments we are familiar with.” Importantly, our emphasis on enabling research near the trunk of the tech tree makes FROs quite different from commercial or translational efforts that aim only to bridge the “valley of death” from lab to market.

The challenges

We knew when we articulated the FRO concepts in 2020 that there would be steep cliffs, stumbles, and surprises. But after launching multiple organizations, we found some concerns were less of a hurdle than we thought, while some strategies were less straightforward than we anticipated. Here’s some of what we learned that the FRO-curious might find helpful.

Early on, one common worry was whether promising scientists would be willing to work in tight-knit teams. Would they forgo the intellectual satisfaction that comes with academic freedom to build concrete infrastructure that enables research more broadly? Would working in an untested sort of research organization have appeal compared to the potential for decades of job security in academia or fortune-making equity in industry?

Today, we couldn’t be more pleased by the answers. Our FRO founders, leaders, and technical staff have led large projects at other institutes, helped found major corporate research labs, held positions in industry and government centers, and risen to top faculty positions, including chairs of academic departments. We’ve had Nobel laureates approach us to see if our model is the best option for advancing a promising project. That said, even with competitive salaries, FROs must work hard to compete with major tech companies for some high-level, highly remunerated positions. Yes, top recruits to FROs must be lured by the mission as well, but attracting talent is not an obstacle for this kind of research.

By contrast, we had a lot to learn about how to set milestones.In many FRO proposals, we modeled milestones on those from organizations like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which write specific, quantitative intermediate (and final) goals into their performance contracts. But even in the fast-paced and focused research environments we’re trying to build, science doesn’t run on a clock. It can be hard to forecast exactly what the right milestones will be years in advance, and hands-on experience with failure is the best source of real learning. We’ve found it better to shift from rigid goals to a well-articulated North Star, specific but adaptive intermediate goals, and a highly dynamic framework for tactical next steps, in which near-term goals are remapped several times every year as the team moves toward achieving the larger aims.

Although many start-ups follow a similar strategy, we discovered we couldn’t import their model wholesale either. In a start-up, there are many clear markers of progress, sometimes called key performance indicators, such as “raise the next funding round,” “increase the number of users,” or “grow revenue.” However, these do not easily map to the task of building fundamental research capabilities. Accordingly, we now advise FRO leaders to adopt several different kinds of milestones: high-level impact targets and go/no-go points to assess the premise of a project and, perhaps, justify preemptive abandonment, plus intermediate milestones to build confidence or pivot to another approach. Internal road maps help set FRO team priorities, the order of operations, and practical quarterly objectives such as “onboard the lab manager,” “host a successful team off-site,” or “rerun sample set 57.”

To accelerate research, any new tool or dataset needs an active userbase, and that demands extensive development of external relationships and an entrepreneurial bent.

An attendant challenge is developing coherent milestones that can be communicated to funders (and sometimes a set of funders, with different priorities), customers, and other stakeholders. FROs with multiple workstreams—one developing both software tools and lab-based hardware, for example—have even more complexity to manage. We’ve discovered that Convergent Research can serve FROs by playing a “mission control” role in these cases. By offering operational and governance support (serving as an intermediary to funders, facilitating tech transfer, and sitting on FRO boards), Convergent can hold teams accountable to the most critical milestones, help them advocate for pivots, and guide reconfigurations of an executive team or major changes in long-term strategy. These can be complex challenges to work through, so we’ve found that cultivating a culture of optimism and commitment to the mission goes far when FROs navigate difficult transitions in their strategy and personnel.

Another common challenge occurs with project and team management.Some founders struggle with the need to make high-consequence decisions quickly, to “ship” real-world results before they feel perfect, or to manage a rapidly growing, shifting team of employees. Theskills and management strategies required to run large projects are rarely taught to scientists in graduate school. We now recommend that FRO leaders have executive coaches and that they bring in operational and technical leads with industry experience early on.

Another way to support a culture of good management is to explicitly build community, so skills and strategies can spread across FROs. We are beginning to experiment with onboarding cohorts, as in our ARIA residency program. We also provide some centralized human resource functions, as well as board- and peer-level mentorship.

One challenge common to all research endeavors is the need to raise funds, but doing so is even more difficult when a fast-moving FRO needs a midstream infusion of money. Accordingly, Convergent pushes teams to think carefully about the budgets they really need and to figure out just how lean they can be. We work with FROs to secure as much of their needed budget as possible from the start, ideally from a mix of mission-aligned funders. We are also working to build long-term relationships with prospective FRO funders that can be leveraged across the entire portfolio, as well as developing alternative funding models. We particularly want mechanisms and funding streams that allow us to start projects with just enough resources to confront an initial set of challenges and thus diagnose whether a full-sized FRO is really practical.

External relationships are critical at all stages to keep an FRO lean and focused. For example, Forest Neurotech, an FRO that is developing minimally invasive brain-computer interfaces, partnered with Butterfly Network to access the latter’s ultrasound-on-chip technology early on, saving Forest months of work and risk. Likewise, [C]Worthy partnered with the established climate data nonprofit CarbonPlan to package and disseminate its carbon removal quantification models, and the Parallel Squared Technology Institute has ongoing collaborations with both academics and contract research organizations.

It’s also become increasingly clear that FROs need Convergent to serve as a matchmaker and relationship builder. We’ve therefore learned to leverage our network across many fields, bringing together a suite of vetted vendors plus experts in areas like metascience and technology development.

Finally, unlike an academic lab, we’ve learned that an FRO’s path to success must involve a kind of product development. Establishing proof-of-concept is not enough to move even a potentially transformative resource into broader use. To accelerate research, any new tool or dataset needs an active userbase, and that demands extensive development of external relationships and an entrepreneurial bent.

An FRO doesn’t need to bring technology all the way to mainstream adoption during its lifetime, but for us to consider it a worthwhile project it needs at least to point toward a new way for practitioners in a field to conduct experiments or create new technologies. We define true success as a “scaled revolution” across an entire field, akin to the changes across biology, medicine, and so much else enabled by the Human Genome Project and subsequent improvements in sequencing technologies. For some FROs, pursuing this goal means organic open source tool dissemination (like many mathematicians adopting the Lean language for writing and checking math proofs). For others, it means integrating into a megaproject elsewhere (e.g., a brain-mapping technology could be adopted into a neural connectome project). And still other FROs might deploy through commercialization or fee-for-services.

Building social scaffolding to enable FROs’ transition into follow-on activities is critical. Like federal Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) program managers, FRO founders need to build and nurture an ecosystem. They must also, as former DARPA head Arati Prabhakar says of ARPA programs, “bring implementers along on the journey from wild dream to demonstrated reality” by showing them what is possible and why they should act. Indeed, the ARPAs for energy and for health (ARPA-E and ARPA-H) both have dedicated staff to help move innovations into the world. Convergent is creating similar processes. In addition to traditional scientific advisory boards, each FRO recruits an impact committee of experts tasked to provide advice and connections to help FROs move toward dissemination.

The FRO future

Our early road-mapping work suggests there is currently a finite number of foundational missing capabilities, perhaps 100 to 200, that yield FRO-shaped problems. That’s still many more than Convergent can support, so we are exploring new funding mechanisms and partnerships, including with government agencies.

We’ve been encouraged that other organizations have begun to embrace the FRO model. Our work with ARIA is likely to result in creation of at least one new FRO supported by the United Kingdom. In addition, the British government’s Research Ventures Catalyst program has, after a competitive application process, provided initial support for another FRO, Bind Research, which will work to model small-molecule interactions with “disordered proteins” and so render them more amenable to conventional drug discovery efforts.

In the United States, Caleb Watney of the Institute for Progress has proposed an “X-Labs” model for funding research. The proposal calls for “X02” execution awards to conduct what resemble FRO projects and “X03” experimentation or institutional block grants, roughly similar to an incubator or mission control like Convergent, to scout, launch, operate, and transition the FROs. Recently, the White House’s AI Action Plan recommended long-term agreements with FROs to accelerate AI innovation and support AI-enabled science.

Four years on, we are more convinced than ever that a directed approach can identify critical bottlenecks in research that can be alleviated with new technology. Often, developing that technology will require something like an FRO: a custom-built team with a clear technological strategy, plus a commitment to making and disseminating public goods.

Right now, Convergent Research is the only organization we know of dedicated to creating FROs, so there is ample room for government, philanthropy, or public-private partnerships to forge their own pathways to launch FROs. We hope that FROs soon become a routine and accessible part of how humans do science, at least until the limiting factors in research progress shift to problems of a different form.

As AI accelerates scientific research and social change, Convergent is considering its priorities. Alongside our work in areas like astrophysics and biology, we are investigating the roles FROs can play in generating new approaches for urgent emerging problems like controlling AI systems, biosecurity, cybersecurity, information technologies supporting scalable and informed democratic deliberation, and coral reef protection in a changing climate. All these challenges are vast, but the more effort we put into finding ways to accelerate science, the better we will get at doing so.