Fighting Innovation Mercantilism

A growing number of countries have adopted beggar-thy-neighbor innovation policies in an effort to attract or grow high-wage industries and jobs, making the global economy less prosperous in the process.

Despite the global economic downturn, indicators of global innovative activity have remained strong during the past two years. The total global output of scientific journal papers in all research fields for the United States, the European Union (EU), and Asia-Pacific nations reached historic highs in 2009. The World Intellectual Property Organization’s 2010 World Intellectual Property Indicators index found that in 2008, the most recent year for which information is available, both the total number of global patent applications received and patent awards granted topped any previous year. And global trading volume in 2010 is on pace to rebound 9.5% over 2009 levels. Yet notwithstanding these indicators of strength, all is far from well with innovation and trade in the global economy.

To be sure, during the past decade, countries worldwide have increasingly come to the realization that innovation drives long-term economic growth and quality of life improvement and have therefore made innovation a central component of their economic development strategies. In fact, no fewer than three dozen countries have now created national innovation agencies and strategies designed specifically to link science, technology, and innovation with economic growth. These nations’ innovation strategies comprehensively address a wide range of individual policy areas, including education, immigration, trade, intellectual property (IP), government procurement, standards, taxes, and investments in R&D and information and communications technology (ICT). Consequently, competition for innovation leadership among nations has become fiercely intense, as they seek to compete and win in the highest-value-added sectors of economic activity, to attract R&D and capital expenditure investment from multinational corporations, to field their own globally competitive and innovative firms and industries, and to generate the greatest number of high-value-added, high-paying employment opportunities possible for their citizens.

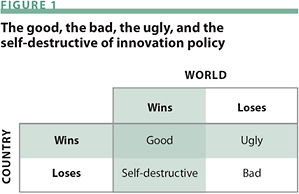

However, countries’ focus on innovation as the route to economic growth creates both global opportunities and threats, because countries can implement their innovation strategies in either constructive or destructive ways. Specifically, as Figure 1 shows, countries can implement their innovation policies in ways that are either: “good,” benefitting the country and the world simultaneously; “ugly,” benefitting the country at the expense of other nations; “bad,” appearing to be good for the country, but actually failing to benefit either the country or the world; or “self-destructive,” failing to benefit the country but benefitting the rest of the world.

Ideally, countries would implement their innovation policies in a positive-sum fashion that is consistent with the established rules of the international trading system and that simultaneously spurs domestic innovation, creates spillover effects that benefit all countries, and encourages others to implement similar win-win policies. But another path countries are unfortunately all too often taking seeks to realize innovation-based growth through a zero- or negative-sum, beggar-thy-neighbor, export-led approach. At the heart of this strategy lies a misguided economic philosophy that many nations have mistakenly bought into: a mercantilism that sees exports in general, and high-value-added technology exports in particular, as the Holy Grail to success. This approach is designed around the view that achieving growth through exports is preferable to generating growth by raising domestic productivity levels through genuine innovation. Indeed, there is disturbing evidence that the global economic system has become increasingly distorted as a growing number of countries have embraced what might be called innovation or technology mercantilism, adopting beggar-thy-neighbor innovation policies in an effort to attract or grow high-wage industries and jobs, making the global economy less prosperous in the process.

These nations, of which China is only the most prominent, are not so much focused on innovation as on technology mercantilism, specifically the manipulation of currency, markets, standards, IP rights, and so forth to gain an unfair advantage favoring their technology exports in international trade. Such policies aren’t designed to increase the global supply of jobs and innovative activity, but rather to induce their shift from one nation to another, usually from consuming to producing nations. Specifically, countries practicing innovation mercantilism use their trade and innovation policies to help their manufacturing and ICT sectors move up the value chain toward higher-value-added production by applying a number of trade-distorting measures. Governments implement these policies to keep out foreign high-technology products while benefiting their own in an effort to boost local production (ideally to fill demand in both domestic and foreign markets) in order to satisfy domestic labor demand.

Practicing innovation mercantilism

A number of ugly and bad innovation practices pervade countries’ currency, trade, tax, intellectual property, government procurement, and standards policies. Perhaps the most pervasive and damaging mercantilist practice is the rampant and widespread currency manipulation that many governments engage in today. Countries manipulate their currencies, either by pegging them to the dollar at artificially low levels or by propping them up through government interventions in an attempt to shift the balance of trade in their favor. Mercantilist countries’ artificially low currencies are a vital component of their export-led growth strategies, making their exported products cheaper and thus more competitive on international markets while making foreign imports more expensive. The overall intent is to induce a shift of production from more productive and innovative locations to less productive and innovative ones.

For example, the Peterson Institute for International Economics argues that China undervalues the renminbi by about 25% on a trade-weighted basis and by about 40% against the U.S. dollar. China’s government strictly controls the flow of capital into and out of the country, as each day it buys approximately $1 billion in the currency markets, holding down the price of the renminbi and thus maintaining China’s artificially strong competitive position. China has actually doubled the scale of its currency intervention since 2005, now spending $30 billion to $40 billion a month to prevent the renminbi from rising. This subsidizes all Chinese exports by 25 to 40%, while placing the effective equivalent of a 25 to 40% tariff on imports, discouraging domestic purchases of other countries’ products. Such currency manipulation is a blatant form of protectionism. Nor is China alone in intervening in markets to manipulate the value of its currency. Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, and even Switzerland—in part in an effort to remain competitive with China—also intervene in currency markets and substantially undervalue their currencies against the dollar and other currencies. For instance, on September 16, 2010, Japan intervened in world currency markets to drive down the exchange rate of the yen by selling an estimated 2 trillion yen ($23 billion)—the largest such intervention ever—in an effort to devalue the yen against the dollar and make Japanese exporters more competitive.

Although a major focus of the international trading system in recent decades has been to remove tariff barriers, countries have gone to great lengths to evade tariff-reduction commitments, and high tariffs persist on a number of high-tech products and services. For example, despite being a signatory to the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Information Technology Agreement (ITA), the EU has attempted to rewrite descriptions of certain ICT goods in an effort to circumvent their coverage under the ITA. In 2005, the EU applied duties of 14% on liquid crystal display televisions larger than 19 inches, and in 2007 the EU moved to allow duties on set-top boxes with a communications function as well as on digital still-image and video cameras. Although the United States won this trade dispute with the EU on August 16, 2010, when a WTO panel ruled that the EU’s imposition of duties on flat-panel displays, multifunction printers, and television set-top boxes violated the ITA, the case was emblematic of countries’ attempts to circumvent trade agreements to favor domestic production from ICT firms and industries.

Meanwhile, a number of countries, even many that are signatories to the ITA, including Indonesia, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Turkey, continue to impose high tariffs on ICT goods. India imposes tariffs of 10% on solid-state, non-volatile storage devices; semiconductor media used in recording; and television cameras, digital cameras, and video camera recorders. Malaysia imposes duties of 25% on cathode-ray tube monitors. The Philippines imposes tariffs of up to 15% on telephone equipment and computer monitors. Countries that have not acceded to the ITA place even higher tariffs on ICT products. China, despite its massive trade surplus with the rest of the world and its signing of an ITA-accession protocol, places 35% tariffs on television cameras, digital cameras, and video recorders; 30% tariffs on cathode-ray tube monitors and all monitors not incorporating television reception apparatus; and 20% on printers and copiers.

A favored practice of innovation mercantilists is to force foreign companies to accept IP, technology transfer, or domestic sourcing of production requirements as a condition of market access. Although the WTO prohibits countries from requiring companies to comply with specific provisions as a condition for market access, such tactics are nevertheless popular because they help countries obtain valuable technological know-how, which they can then use to support domestic technology development in direct competition to the foreign firms originally supplying it.

China is a master of the joint venture and R&D technology transfer deal. In the 1990s, when the country began aggressively promoting domestic technological innovation, it developed investment and industrial policies that included explicit provisions for technology transfer, particularly for collaboration in production, research, and training. The country uses several approaches. One is to get companies to donate equipment. Others include requiring companies to establish a research institution, center, or laboratory for joint R&D in order to get approval for joint ventures. Because the WTO prohibits these types of deals and China has since become a WTO member, it now hides them in the informal agreements that Chinese government officials force on foreign companies when they apply for joint ventures. They also sometimes require other WTO-violating provisions, such as export performance and local content, to approve an investment or a loan from a Chinese bank. China thus continues to violate the WTO, only more covertly, acquiring U.S. and other countries’ technology and paying nothing in return. Foreign companies continue to capitulate because they have no choice; they either give up their technology or they lose out to other competitors in the fast-growing Chinese market.

One of the most insidious forms of innovation mercantilism concerns outright IP theft. Yet many countries continue to pilfer others’ IP because it’s easier than making expensive investments themselves, and because, according to research by Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman, at least in the short-term, IP theft works. However, IP theft stifles incentives to embark on home-grown technology development, thus hurting countries and making IP theft a bad strategy in the long-run. For example, in 1999 Brazil passed its Generics Law, which allowed companies to produce generic drugs that are perfect copies of patented drugs, a clear violation of the WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement. Although Brazil’s policy has nominally helped its consumers by forcing foreign pharmaceutical companies such as Abbott Laboratories to sell drugs significantly below market prices, not only do the countries where the drugs are produced suffer, but the rest of the world suffers because there is less pharmaceutical R&D conducted, and therefore fewer drug discoveries made. Moreover, Brazil’s insistence on tampering with IP rights has damaged the development of its pharmaceuticals industry and discouraged foreign direct investment in the country, redirecting it to other countries such as Mexico and South Korea, which makes this an example of a “self-destructive” innovation policy. Likewise, evidence shows that the lack of effective protection for IP rights has limited the introduction of advanced technology and innovation investments by foreign companies in China.

Innovation mercantilists also manipulate government procurement practices to their advantage. For example, China has introduced indigenous innovation policies explicitly designed to discriminate against foreign-owned companies in government procurement. In November 2009, China announced an indigenous innovation product-accreditation scheme—a list of products invented and produced in China that would receive preferences in Chinese government procurement. To be eligible for preferences under the originally conceived program, products would have had to contain Chinese proprietary IP rights, and the original registration location of the product trademark had to be within the territory of China, practices well outside international norms. China’s indigenous innovation policies have already begun to negatively affect foreign firms’ ability to sell to China’s massive government procurement market, clearly contributing, for example, to foreign producers’ share of China’s wind turbine market cratering from 75% in 2004 to 15% in 2009. Worse, although it’s bad enough that Microsoft estimates that 95% of the copies of Microsoft’s Office software in China are pirated, at least 80% of China’s government computers use versions of the Microsoft Windows operating systems that were illegally copied or otherwise not purchased. It is no wonder the United States runs an outlandishly large trade deficit with China when U.S. consumers, businesses, and government agencies pay for their products and services, but even their government fails to pay for ours.

Why countries use mercantilist practices

Countries employ mercantilist policies because they hold one or more of four beliefs: that goods, particularly tradable goods, constitute the only real part of their economy; that moving up the value chain is the primary path to economic growth; that they should become autarchic, self-sufficient economies; or that mercantilist policies actually do work.

Many nations believe that goods constitute the only real part of their economy through which they can drive a growth multiplier, and they therefore view exports and large trade surpluses as good (and imports bad), in and of themselves, as targets of economic policy. Indeed, building their economies around high-productivity, high-value-added, export-based sectors, such as high-tech or capital-intensive manufacturing sectors, appears to be the path that nations such as China, Germany, Indonesia, Malaysia, Russia, and others are following, in the footsteps of Japan and the Asian tigers Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan before them.

Furthermore, these nations believe that the primary path to economic growth lies in moving up the value chain from low-wage, low-value-added industries to high-wage, high-value-added production. Many of these countries are willing to engage in what is essentially predatory pricing on international markets, sacrificing short-term losses in order to grow long-term production. By doing so, they hope to erode the production base of advanced industrial nations, with the goal of ultimately knocking industry after industry out of competition in order to reap long-term job gains.

Some countries pursue mercantilist, export-led growth strategies out of a desire to realize national economic self-sufficiency. China’s current economic strategy could perhaps best be described as autarky: a desire to become fully economically self-sufficient and free from the need to import goods or services, especially high-technology ones. Chinese policy appears to identify every single flow of money exiting the country and shut off the spigot, an ambition evident in China’s efforts to establish a domestic base of commercial jet aircraft production and in its desire to establish indigenous standards across a range of technologies so it need not make royalty payments on IP embedded in foreign technology standards.

But the primary reason countries purse mercantilist strategies is the belief that they work. Although U.S. policy has long held that mercantilists only hurt themselves, the reality is that, although some mercantilist policies that countries think will help them do backfire and end up hurting them (the bad and self-destructive ones), many mercantilist practices actually do work (the ugly ones) and help these countries gain competitive advantage, at least temporarily, especially if other countries fail to contest such practices. China’s ugly practices, such as currency manipulation and forced IP transfer, have clearly boosted the country’s exports, moved productive activity to its shores, and hurt foreign producers. The “success” of China’s mercantilist practices is reflected in the country’s share of world exports jumping from 7 to 10% between 2006 and 2010, in the country’s $400 billion and $426 billion current account (trade) surpluses in 2007 and 2008, respectively, and its accumulation of $2.65 trillion of foreign currency reserves. This creates a vicious cycle. Seeing the success of such mercantilist practices, other countries are enticed, even compelled, to introduce similar practices.

Unsustainable in the long-run

Yet despite their apparent attractiveness, mercantilist practices represent a flawed strategy for several reasons. First, they are fundamentally unnecessary and counterproductive; countries have much more effective means at their disposal to drive economic and employment growth. Second, they place the wrong focus on economic growth, neglecting the far greater and more sustainable opportunity to drive economic growth by raising productivity across the board, particularly in the non-traded domestic sectors of an economy, especially through the application of ICT. Third, export-led mercantilism is fundamentally unsustainable for both the country and the world. Fourth, many mercantilist practices, especially those distorting ICT and capital goods sectors, are of the bad variety, failing outright. Finally, mercantilist strategies contravene the established rules of the international trading system and undermine confidence in trade’s ability to produce globally shared prosperity, thus reducing global consumer welfare.

Although mercantilist countries, and the apologists who defend them, argue that the only way they can grow is through high-value-added exports that run up massive trade surpluses as if they were collecting gold bullion, the notion that the only way countries can achieve a full employment economy is by manipulating the trading system to run ever-growing trade surpluses is flat wrong. It contradicts basic macroeconomics, which observes that a change in gross domestic product equals the sum of the changes in consumer spending, government spending, corporate investment, and net exports (exports minus imports). In other words, mercantilist countries could grow just as rapidly, and probably even more so, by pursuing a robust domestic expansionary economy that drives growth through increased domestic consumption and greater business or government investment.

In effect, mercantilist countries mistakenly believe that promoting exports rather than increasing productivity across the board is the superior path to economic growth. Yet it is productivity growth—the increase in the amount of output produced by workers per a given unit of effort—that is the most important measure and determinant of a nation’s economic performance. Indeed, the lion’s share of productivity growth in most nations, especially large- and medium-sized ones, comes not from altering the sectoral mix toward higher-productivity industries, but from all firms and organizations, even low-productivity ones, boosting their productivity. Put succinctly, the productivity of a nation’s sectors matters more than a nation’s mix of sectors, and this means mercantilist countries could grow more reliably and sustainably if they focused on raising the productivity of all sectors of their economy, not just propping up their export sectors.

Perhaps the greatest weakness of countries’ export-led growth strategies is that they are unsustainable. Neither markets in the United States nor Europe (minus Germany), nor even both combined, are large enough if nations such as Brazil, China, Germany, Japan, and Russia continue to promote exports while limiting imports as their primary path to prosperity. Moreover, a predominantly export-led focus is unsustainable for countries themselves. For example, Japan boasts many world-leading exporters of manufactured products, but because it has never really focused on the non-traded sectors of its economy, only about one-quarter of its economy is growth-oriented. It can’t boast of any world-class services firms, and it trails badly in the use of ICT. Countries such as Argentina, China, Japan, India, and South Korea have been far more concerned with producing ICTs than consuming them. But what these countries have missed is that the vast majority of economic benefits from these technologies, as much as 80%, come from their widespread use across a range of industries, whereas only about 20% of the benefits of ICTs comes from their production. As Erik Brynjolfsson of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has noted, it’s about how firms such as Wal-Mart use ICT products to revolutionize their industries, not where those products are manufactured, that truly drives countries’ productivity and economic growth. But most mercantilist countries have been more concerned with manufacturing and selling ICT (and other high-value-added) products than applying them to make their own domestic service industries more productive and competitive.

For these reasons, mercantilist policies placing high tariffs or other import restrictions on general purpose technologies such as ICT products are purely bad and fail outright. Such policies have the effect of raising the cost of domestic ICT and making local industries that need to leverage these technologies less competitive. For example, as part of its import substitution industrialization strategy, for many years India placed high tariffs on ICTs in an effort to keep out foreign ICT products and spur the creation of a domestic computer manufacturing industry. But research finds that, for every $1 of tariffs India imposed on imported ICT products, it suffered an economic loss of $1.30. Such policies served only to raise the price of ICTs for domestic players, inhibiting the diffusion of IT throughout domestic service sectors such as financial services, retail, and transportation, and causing productivity growth in these sectors to languish.

Getting innovation policy right

There is nothing wrong with countries engaging in fierce innovation, economic, and trade competition, so long as they are competing according to the rules of international trade. In fact, when a county intensely competes to win within the rules of the system, doing so benefits both itself and the world. This is because fair competition forces countries to put in place the right policies for the support of science and technology transfer, the right R&D tax credit policies, the right corporate tax policies with lower tax rates, the right education policies, etc. So when the United States introduces an R&D tax credit, or France trumps the United States by offering a credit six times more generous, or Denmark creates innovation vouchers for small businesses, or the Netherlands and Switzerland tax profits generated from newly patented products at just 5%, this is all tough, fair competition that forces other countries to raise their games in kind by enacting their own good innovation policies. The problem comes when countries start to cheat and contravene the global economy’s established rules. Ugly practices can indeed help countries win. But not only do such policies harm other countries, they then encourage other countries to cheat, undermining the structure of the international trading system. This causes the system to devolve into a competition in which every country has incentives to cheat and to engage in beggar-thy-neighbor policies. Thus the overall system decays, the competition becomes worse, and the global economy suffers as all countries fight for a slice of a smaller pie.

Countries committed to good innovation policies must abandon the notion that countries employing mercantilist policies are somehow going to play by the rules if we just play nice with them. They must agree to cooperate to fight it, not just to talk about it.

It is time for a new approach to globalization. The United States and like-minded countries should strive to develop a global consensus around good innovation policy, with a large focus on domestic-led service innovation through the application of IT. This renewed vision for globalization should be grounded in the perspectives that markets drive global trade; that in addition to joining and adhering to the WTO, countries should become signatories to major trade agreements, including the Government Procurement Agreement, the ITA, and TRIPS; that genuine, value-added innovation, especially that which spurs productivity, drives economic growth; that foreign aid policies should not support countries’ mercantilist strategies; and that fair competition forces countries to ratchet up their game by putting in place constructive innovation policies that leave all countries better off. This holds a number of implications for policymakers.

First, policymakers, both in the United States and abroad, must recognize that innovation mercantilism constitutes a threat to the global innovation system. In the United States, there has been mostly denial or indifference about the impact of countries’ mercantilist policies, encapsulated in the mistaken attitude that because mercantilists only hurt themselves, their policies aren’t a concern. As a U.S. congressman argued at a recent Washington conference, “We don’t really need to worry if the Chinese subsidize their clean energy industry, because American consumers benefit.” But this perspective fails to understand that although consumers may benefit from cheaper imports, U.S. workers suffer as production increasingly moves offshore, and as U.S. unemployment rises, in part as a result of foreign mercantilism, this only erodes confidence in globalization’s ability to deliver shared and sustained long-term prosperity. That’s why it is critically important for policymakers to be able to distinguish the good innovation policies from the ugly and bad ones, so they can promote those that benefit countries and the world simultaneously, while pushing back against those that benefit countries at the expense of other nations. Additionally, policymakers worldwide must recognize that the only sustainable path to raising living standards for the vast majority of citizens in developed and developing countries alike will be to leverage innovation to raise economies’ productivity across the board in all firms and all sectors.

Second, developed countries need to work alongside international development organizations to reformulate foreign aid and development assistance policies to use them as a carrot and stick to push countries toward the right kinds of innovation policies. Foreign aid should be geared to enhancing the productivity of developing countries’ domestic, non-traded sectors, not to helping their export sectors become more competitive on global markets. Blatantly mercantilist countries engaging in IP theft, manipulating currencies, imposing significant trade barriers, etc. should have their foreign aid privileges withdrawn. The message to these countries should be that if they want to engage the global community for development assistance, ugly and bad policies cannot constitute the dominant logic of their innovation and economic growth strategies.

For their part, international organizations must work more proactively to combat nations’ mercantilist strategies. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, WTO, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and others need to not only stop promoting export-led growth as a key development tool, but also tie their assistance to steps taken by developing nations to move away from negative-sum mercantilist policies. In particular, the World Bank should make a firm commitment that it will stop encouraging policies designed to support countries’ export-led growth strategies. The G-20 countries, as the primary sponsors of the World Bank, must tackle this issue head-on and truly begin focusing on win-win global growth through innovation, in part by placing a major focus on how to restructure international institutions to make this happen. For instance, G-20 countries should demand from the World Bank a new strategic plan for how it can completely revamp its approach to reward nations that are playing by the rules and to at least try to minimize the bad and ugly policies of the nations that aren’t.

The WTO must realize that what has been transpiring in the global trading system is not occasional and random infractions of certain trade provisions that need to be handled on a case-by-case basis, but rather that some countries continue to systematically violate the core tenets of the WTO because their dominant logic toward trade is predicated on export-led growth through mercantilist practices. The WTO must commit to stopping such practices. It should also annually publish a list of all new trade barriers, including non-tariff barriers, whether they are allowed by its rules or not

Finally, U.S. trade policy must become much more seriously geared to combating nations’ systematic innovation mercantilism. Currently, however, U.S. as well as European trade policy is organized in a legalistic framework designed to combat unfair trade practices on a case-by-case basis, an enormously expensive and time-consuming process. As a consequence, it becomes difficult for them to put in place a comprehensive trade strategy designed to stimulate competitiveness and innovation.

In addition to a more systematic approach to trade negotiations, the United States also needs to get much more aggressive with trade enforcement and bringing forward WTO cases. Part of the problem is a resource issue. One reason the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) has not done more to enforce existing trade agreements is because doing so is quite costly and labor intensive. Moreover, much of USTR’s budget goes toward negotiating new trade agreements. Congress should increase USTR’s budget with the new resources devoted to enforcement and the fight against unfair foreign trade practices. The United States should also create within USTR an ambassador-level U.S. trade enforcement chief and a Trade Enforcement Working Group. Creating these new entities would send a clear signal that a key part of USTR’s job is to aggressively bring actions against other nations that are engaged in technology mercantilism. The United States should also institute a 25% tax credit for company expenditures related to bringing a WTO case, because government alone cannot fully investigate all potential WTO cases and because companies that do help bring cases are acting on behalf of the U.S. government.

If these measures prove insufficient, it may be time to think about establishing a new trade regime outside of the WTO that would exclude nations that persist in the systematic pursuit of mercantilist policies that violate free trade principles. The Trans-Pacific Partnership could provide a model for how to organize such a new trade zone. The Trans-Pacific Partnership represents a vehicle for economic integration and collaboration across the Asia-Pacific region among like-minded countries—including Australia, Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam, and the United States—that have come together voluntarily to craft a platform for a comprehensive, high-standard trade agreement. The door would be open for all countries to participate, but those that would like to do so would have to abandon wholesale mercantilist practices and demonstrate genuine commitment to free trade principles.

Enough is enough. The stakes are too important. Trade, globalization, and innovation remain poised to generate lasting global prosperity, but only if all countries share a commitment to playing by the rules and fostering shared, sustainable growth. It’s time to end innovation mercantilism and replace it with good innovation policy.