Electric Energy

The conceptual artist Iván Navarro’s work is rich in historical, social, artistic, and political references. Although his sculptures may bring to mind the work of Dan Flavin, an American minimalist artist famous for creating sculptural objects and installations from commercially available fluorescent light fixtures, the ideas behind Navarro’s work are very different. Born in Santiago, Chile, in 1972, Navarro grew up under the Pinochet regime in the 1970s and 1980s. This view of dictatorship informs his choice of material and subject matter—electricity—which, beyond its alluring appearance, evokes darker themes of surveillance, torture, imprisonment, and domination. Under Pinochet, frequent blackouts kept citizens in a state of subservience and fear, and people who were interrogated were often tortured with electricity. Navarro learned about the full extent of the human rights abuses in Chile only when he moved to New York in 1997.

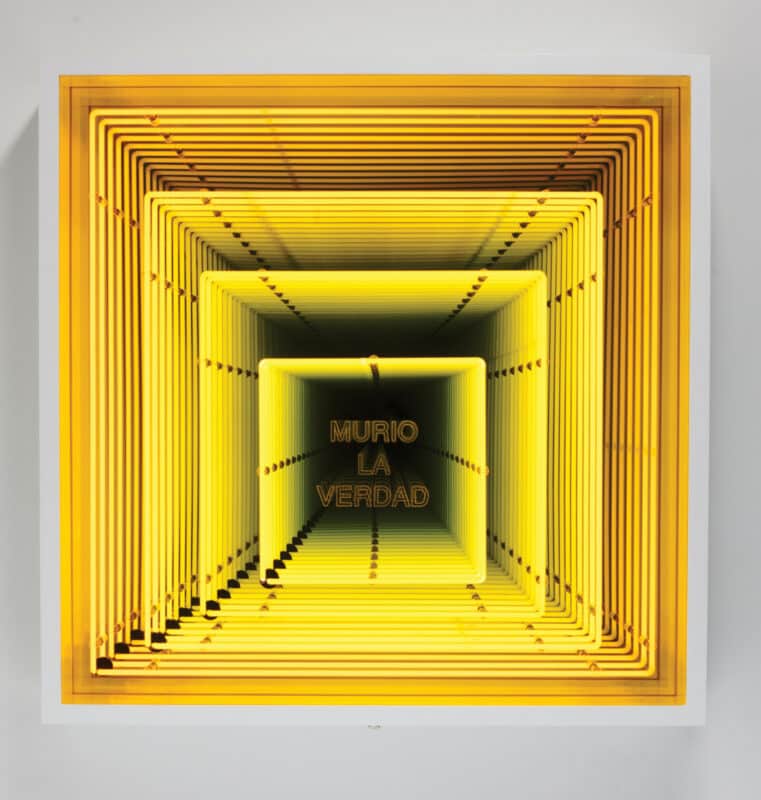

Navarro’s work with electricity, though, does not confine itself to Pinochet’s crimes in Chile. One of his earlier works, You Sit, You Die (2002), is a commentary on the electric chair that is made from fluorescent lightbulbs. On its paper seat he printed the names of everyone who had been executed in Florida by electrocution. In many pieces, he explores language and wordplay, incorporating phrases such as Murio La Verdad (Truth has Died) (2013) and No Se Puede Mirar (Cannot Look) (2013) into neon sculptures to probe questions of power and control. In other works, he uses mirror reflections and light to make a word appear to repeat infinitely (Bed, 2009) so that viewers might begin to think differently about the word’s meaning.

He turns functional objects—an escape ladder, a bench, a fence, traffic lights, a shopping cart, a surveillance booth—into sculptures as a way to encourage people to see them anew and to consider their other possible meanings. Navarro began transforming everyday objects into sculptures while he was still living in Chile, where there weren’t many places to exhibit art. But Navarro realized that if a sculpture could double as a functional object, it might be displayed in a building lobby or someone’s home. He explains, “One of my ideas was to make lamps and use the electrical systems of places because the only way to show art was to make it functional. The idea was basically to make a sculpture, but a subversive one. It looked like a lamp, but was a sculpture.”

Navarro created his latest series, Planetarium, in isolation during the pandemic. Collecting images of nebulae taken by powerful telescopes all over the world, he used paint and paintbrushes in his work for the first time. This handmade approach was a response to COVID-19—partially out of necessity due to a sudden lack of access to fabricators, and partly because the hand work was cathartic. Repeating the same movement over and over, he engraved one-way mirrors, painted and poured vivid colors into them, and incorporated LED lights to create abstract representations of cosmic landscapes and celestial phenomena. “Observing the stars is like touching the greatest secrets of the universe with your fingertips,” Navarro says. This body of work enabled him to experiment with a new artistic process and to embrace the inevitable scratches that he had painstakingly tried to avoid in previous mirror and light work. The finished pieces raise metaphysical questions at a moment when many of us are reflecting on the state of humanity and our place in the universe.

In early 2021, Navarro had two exhibitions of Planetarium on view in Paris: at Le Centquatre-Paris and at Galerie Templon. In 2009, he represented Chile at the 53rd Venice Biennale. His work has been shown at major museums including the Museum of Contemporary Art of Buenos Aires; the Busan Museum of Art in South Korea; the Imperial War Museum in London; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. In 2020, a permanent installation, The Ladder, was inaugurated on a building in San Francisco. He is currently working on a large installation for the Paris Metro based on the stars that can be seen from Earth with the naked eye.

—Text by Alana Quinn

Iván Navarro, Emergency Ladder, 2018; ruby red neon light and curved electrodes; 72 × 24 × 5 7/8 inches. © Courtesy Gallerie Templon, Paris – Brussels.

Iván Navarro, Traffic, 2015; traffic lights and electric energy; 216 1/2 x 216 1/2 inches. © Courtesy Gallerie Templon, Paris – Brussels.