Does Education Pay?

Yes and no. It depends on what, where, and how long one studies—but the outcomes do not align with conventional wisdom.

Higher education is one of the most important investments that people make. Whereas most academics emphasize the nonpecuniary benefits of higher education, most students making this investment are seeking higher wages and good careers. For example, in the latest Higher Education Research Institute survey of incoming first-year students at four-year colleges and universities, 88% agreed that the most important reason to go to college is to get a good job. And increasingly, government policymakers who vote on the billions of dollars of subsidies that support higher education are also asking about the return on taxpayers’ investment. Concern for labor market returns may infuriate many academics, but it is today’s reality.

Therefore, collecting data on wage outcomes for graduates of higher education programs has become ever more important. The American Institutes for Research and the Matrix Knowledge Group decided to form an independent organization called College Measures that would focus on collecting and analyzing data, especially wage data, to inform education leaders and prospective students and thus drive improvement in higher education outcomes in the United States.

Surprises in the data

In a major effort launched in 2013, College Measures (with support from the Lumina Foundation) has worked with five states to link postsecondary student-level data with wage data for those graduates and to make the results easily accessible to the public. The five states are Arkansas, Colorado, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. Examining the data reveals four key patterns that are likely to surprise anyone who spends most of his or her life thinking about and working in elite institutions and strong research departments.

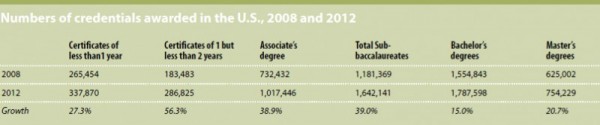

Some short-term higher education credentials are worth as much as long-term ones. Although most people probably think of a bachelor’s degree when they think of a college degree, in 2013 the nation’s system of higher education, mostly through community colleges, granted almost as many shorter-term credentials—including associate’s degrees and occupationally oriented certificates—as bachelors’ degrees (see Table 1). And the number of sub-baccalaureate credentials awarded is growing far faster than either the number of bachelor’s or master’s degrees awarded.

More than 1 million students earned associate’s degrees in 2013, making it the second most common postsecondary credential granted in the nation. Community colleges, the public institutions that produce most associate’s degrees, have dual missions: preparing some students who are planning to transfer to four-year institutions and preparing others to enter the job market. Among the five states in our study, Virginia best exemplifies the double role: It explicitly labels courses of study in its community colleges as either “bachelor’s credit” or “occupational/technical credit.” Texas recognizes associate’s degrees as “academic” or “technical,” and Colorado offers the transfer-oriented associate of arts/sciences degree as well as the career-oriented associate of applied sciences degree.

What is striking is that in four of the five states in our study, the average first-year earnings of associate’s degree graduates are higher than the earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients. In Tennessee, which does not distinguish between technical and academically oriented degrees, associate’s degree graduates earn over $1,300 more in their first year after graduation than do bachelor’s graduates. In Texas, Colorado, and Virginia, where we can identify which track each graduate took, the wage premium for technical associate’s degrees is even greater. Texas graduates with technical associate’s degrees earn in excess of $11,000 more in the first year after graduation than do other bachelor’s graduates statewide. In Colorado, graduates with associate of applied sciences degrees out-earn bachelor’s degree graduates by over $7,000 statewide. The gap in Virginia is smaller, only $2,000, but remember that the technical associate’s degree is faster and cheaper to earn than a bachelor’s degree, so even a $2,000 gap implies a better return on investment.

In contrast, graduates from transfer-oriented associate’s degree programs in the job market after completion lag both their peers graduating from technical programs and bachelor’s degree graduates. For example, students in Colorado who earn associate of arts/sciences degrees lag technical/career completers by $15,000 and lag bachelor’s graduates by $8,000. In Virginia, the gap is smaller but still substantial: $6,000 between technical associate’s graduates and bachelor’s credit graduates, and $4,000 between bachelor’s graduates and bachelor’s credit associate’s graduates. The biggest gaps are in Texas, where over $30,000 separates the two types of associate’s graduates, and $19,000 separates academic associate’s graduates from bachelor’s graduates.

In short, technical/career-oriented associate’s degrees can help launch graduates into well-paying jobs. For students who are trying to use the associate’s degree as a pathway into a bachelor’s program but are in the labor market, the value of the degree is far less.

Even as the value of the technical associate’s degree is becoming clear, community colleges are granting an increasing number of even more career-oriented credentials in the form of certificates. In 2013, more than 600,000 certificates were awarded. Given the ballooning costs of college and an uncertain job market, it is probably not surprising that students are enrolling in these programs in growing numbers. Certificates, which often cost less than an associate’s degree, promise success in the job market, according to a number of studies.

Despite the rapid growth of certificates, the federal government has not yet caught up with the growing importance of this credential. For example, whereas the nation has in practice agreed that an associate’s degree encompasses an average of 60 hours of study and a bachelor’s degree encompasses 120 hours, certificate programs can last a few months to two years and cover such diverse areas as cosmetology, construction trades, and aircraft mechanics.

The data we have gathered from the states can help shed light on some of the questions surrounding certificates. Perhaps the most interesting comparison is between certificate holders and associate’s degree graduates. One argument often put forward in support of certificates is that they can produce high earnings for completers while requiring less time than a traditional associate’s degree. We find some evidence of this, but much of the truth of this statement depends on the type of associate’s degree and the length of the certificate being compared.

In Colorado, for example, holders of both long- and short-term certificates have higher first-year earnings than students with the transfer-oriented associate of arts/sciences degree who are in the labor market. Similarly, in Virginia, students with a certificate in mental and social health services and allied professions have higher earnings than students who graduated with a bachelor’s credit associate’s degree. In Texas, certificate holders earn almost $15,000 more on average than graduates of academic associate’s programs, but about $15,000 less than students with technical associate’s degrees. In Tennessee, students with long-term certificates out-earn associate’s degree graduates by approximately $2,000, but short-term certificate holders earn about $4,500 less.

In short, certificates of longer duration (1 to 2 years) may represent a viable alternative to an associate’s degree. This is particularly true when comparing certificates with academic transfer-oriented associate’s degrees.

Although longer-term certificates, on average, have market value, there is considerable variation in their value depending on the field in which they are granted. Across the states, certificates in manufacturing, construction trades, and health-related fields generate the most earnings. In Virginia, for example, certificate completers in industrial production technologies ($38,000) and precision metal working ($40,000) have higher first-year earnings than bachelor’s degree graduates ($36,000). Similarly in Arkansas, students completing a certificate in airframe mechanics and aircraft maintenance technology on average earn $8,000 more than the average bachelor’s graduate ($41,000 versus $33,000). In Tennessee, students completing a certificate in construction trades have among the highest average earnings ($61,000) of any program of study we identified in the state. In Texas, students completing certificates in radiography and in hospital/health care facilities management had average earnings of more than $69,000, compared with $40,000 for bachelor’s graduates. In contrast, students completing certificates in cosmetology or culinary arts tended to have far lower salaries.

Where a student graduates from has an impact on earnings, but less than usually thought. There is a whole world of higher education beyond the Ivy League and the state flagships. And although our study has no information on the earnings of Ivy graduates, the state flagship universities are included in the data—and at least judged by earnings, students who do not win admission into these big-name schools need not despair. Of course, it is important to keep in mind that the state flagships do send more students to professional schools and graduate work than do the regional campuses, but most students do not go on beyond the bachelor’s degree, and far more students are educated in the regional campuses than in the flagships.

Several consistent messages emerge from looking at the wages of graduates across institutions. One is that graduates’ first-year earnings range widely. In all five states, at least $18,000 separates the schools where bachelor’s graduates earn the most from schools where graduates earned the least during their first year on the job. The difference between master’s graduates from different institutions ranges from more than $10,000 in Arkansas to more than $40,000 in Tennessee and Texas.

However, each state has schools whose graduates fall far below their peers and, conversely, schools whose graduates outperform peers graduating from other institutions. But while the range is large, within each state a large proportion of schools have graduates who earn roughly the same after graduating. In Colorado, bachelor’s degree holders from 6 of the 15 four-year colleges and universities have median earnings clustered between $37,000 and $39,000. Similarly, bachelor’s graduates from 10 of the 22 four-year institutions reporting from Arkansas have overall first-year earnings that cluster between $30,000 and $34,000.

Graduates from flagships who go straight to work do not, on average, earn more than graduates from many regional campuses. The average first-year earnings of graduates from the University of Texas at Austin ($38,100), for example, are lower than the state median for bachelor’s graduates ($39,700) and lower than graduates from several University of Texas regional campuses (including UT Permian Basin, Pan American, Dallas, and Arlington, with campus medians all over $40,000). Similarly, in Colorado, graduates from the flagship university in Boulder have lower starting wages ($37,700) than bachelor’s graduates from Metropolitan State University ($38,500) and the University of Colorado Denver ($43,800).

It also is notable that in states where private not-for-profit colleges are in the database, including Virginia and Arkansas, graduates from these types of schools often have low first-year earnings. Yet the “net price” of attending these schools can be high. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average net price of attending Hendrix College in Arkansas is over $20,000 per year, but graduates on average made less than $26,000. Similarly, Hollins University in Virginia had an average net price of almost $21,000, just about equal to the first-year earnings of its graduates ($23,776). In contrast, Central Baptist college in Arkansas had a net price of less than $11,000, but its graduates had earnings of over $40,000. We have found in other states that the relationship between price and earnings is not straightforward.

Field of study is more important than place of study. The labor market rewards technical and occupational skills at all of the three degree levels—associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s—that we have studied. Graduates with bachelor’s degrees in music, photography, philosophy, and other liberal arts fields almost always fall at the bottom of the list of majors organized by earnings. In the top slot in every state is an engineering field. In Arkansas, bachelor’s graduates with a degree in music performance overall earn less than $20,000, whereas engineering graduate earn almost three times that ($57,000). In Virginia, graduates with philosophy degrees average just over $20,000 whereas graduates with degrees in petroleum engineering average almost $62,000. Graduates with bachelor’s degrees in business administration usually have overall earnings above the overall wages of bachelor’s degree students statewide (for example, in Colorado, it is $43,000 for business versus $39,000 for all bachelor’s graduates; in Virginia, it is $36,000 versus $33,000 overall).

Until the data about student earnings across the nation are unearthed and put to full use, many students will make poor decisions about schools and programs—decisions that will leave them saddled with debt and clamoring for some kind of government bailout.

Many people who look at these early career data argue that the value of liberal arts degrees emerges in the longer run, because it might take liberal arts graduates longer to launch careers. But will the philosophy major who is now a barista at Starbucks really be a barrister in a large law firm 10 years from now? Although we do not yet have long-term wage data, the data from master’s graduates suggests that those in technical fields fare better that far up the educational ladder.

In Arkansas, for example, master’s graduates in creative writing have overall first-year earnings of less than $30,000. In Virginia, master’s graduates in creative writing earn less than $32,000. In both states, this was the lowest-paid major, whereas nurse anesthesiologist was the highest at about $130,000. In Tennessee, over $36,000 separated the master’s graduates in the lowest-paid fields (foreign languages, literature, and linguistics) from the highest-paid (health professions and related programs).

Overall, as with the associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees in technical fields yield far greater returns than do the liberal arts.

The S in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) is oversold. Politicians and policymakers at the federal and state levels, among many others, have trumpeted the need for STEM education to feed the STEM workforce. But the labor market is far more discriminating in what kinds of degrees it rewards. Our data show that employers are paying more, often far more, for degrees in the technology, engineering, and math parts of STEM. And no evidence suggests that biology majors earn a wage premium. Chemistry majors earn somewhat more, but they do not command the wage premium of engineering, computer/information science, or math majors.

Three of our states—Texas, Colorado, and Virginia—have sufficient numbers of students in large STEM fields to allow an exploration of the link between STEM education and wages. The data show overall that although students in technology, engineering, and math experience greater labor market success than other students, the science fields do not generate any greater labor market returns than, for example, the decidedly not-STEM field of English language and literature. If we take wages as a signal of demand for workers, students with science majors are not in high demand.

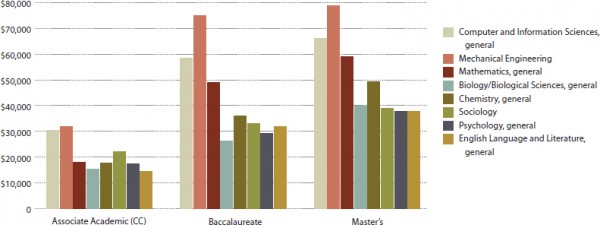

We turn first to Texas. Given the number of students in Texas, we are able to report the first-year earnings of graduates with associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees in all of the major fields of studies we have chosen to investigate (see Figure 1).

At the associate’s degree level, there is a substantial wage increment for graduates with two-year degrees in computer and information sciences ($30,000) and in mechanical engineering ($32,000). However, graduates with associate’s degrees in the three other STEM fields studied fare less well. Their average first-year wages—$17,000 in biology, $18,000 in chemistry, and $18,000 in math—are considerably lower, and even lower than for graduates with associate’s degrees in the non-STEM field of sociology ($21,000).

Looking at the wages of STEM bachelor’s graduates, mechanical engineering graduates earn, on average, more than graduates of any other field—often by a factor of 2. Mechanical engineering graduates earn $74,000, whereas computer/information sciences bachelor’s graduates, the next closest group, earn $58,000. Math majors do well ($49,000), earning more than graduates in most other fields of study. Chemistry majors at $36,000 do better than biology majors ($26,000), who earn less than graduates with degrees in English ($32,000), sociology ($33,000) or psychology ($29,000).

In Virginia, there are fewer data available, but some observations are possible. We have found that graduates in engineering and computer/information sciences earn the most ($52,000 and $51,000, respectively), followed by math majors ($37,000). The average wage of chemistry graduates ($31,000) is only slightly higher than for sociologists ($30,000), psychologists ($29,000), or English majors ($29,000), whereas bachelor’s graduates in biology ($28,000) lag all of these other fields.

This is virtually identical to observations in Colorado, where graduates with degrees in engineering, computer science, and math earn the most. Graduates with chemistry degrees earn slightly more than graduates from other fields, and graduates with biology degrees earn about the same as graduates in sociology or English language arts.

At the master’s level, across the states, graduates with degrees in mechanical engineering, computer/information sciences, and mathematics are the highest paid, with chemistry graduates also earning more than graduates from the remaining fields. In Texas, where biology graduates with master’s degrees increased their earnings by about 50% as compared with biology graduates with a bachelor’s degree (from $26,000 to $40,000), their earnings are within $2,000 of sociology ($39,000), psychology ($38,000), and English ($38,000). In Virginia, master’s graduates in biology ($36,000) are paid virtually the same as master’s graduates in sociology and less than graduates in psychology ($44,000).

These findings show the power of linking student data to wage data. Students and policymakers who have been bombarded by the rhetoric invoking the critical importance of STEM education might assume that majoring in any STEM field will lead to better wages. Yet the objective wage data show that in each state and at each level of postsecondary credentials, graduates with biology degrees, the field that graduates the largest number of science majors, earn no more than sociology or psychology graduates. Chemistry graduates are fewer in number, and we often cannot report wage data for them. But when we can, chemistry graduates usually do slightly better than biology majors, but lag technology, engineering, and math graduates.

Knowing before going

As student debt hits $1 trillion nationwide, better decisions about where and what to study based on likely earnings after graduation could ease students’ financial woes and the nation’s growing debt problem. In a recent article on usnews.com, Mitchell Weiss, a cofounder of the University of Hartford’s Center for Personal Financial Responsibility, presented a valuable rule of thumb: “students should cap their debt based on future earnings . . . You don’t want to borrow more than what you can reasonably expect to earn.” Weiss further advised that students can make sure that their monthly loan payments do not exceed 10% of their income by keeping the total amount borrowed at or below the average first-year earnings for their degree field.

In short, to make well-informed decisions, students need information about the potential earnings of graduates from each school and program under consideration. The states that have partnered with College Measures are working to make this information available to all. (We also are working with the states to improve current efforts in a number of ways; for example, by collecting wage data for students who graduated as many as 10 years ago to improve long-range projections of earnings potential.) A close reading of the data already on hand shows some key lessons about what graduates should take into account while deciding about what degree to pursue and where to get it.

First, the data show the folly of thinking about sub-baccalaureate credentials as “also-rans” in the education derby. True, graduates with four-year bachelor’s degrees usually earn more than those with associate’s degrees over their lifetimes, but graduates with associate’s degrees and many certificates can command a solid wage and, in the early post- college years, make as much as, or even more than, graduates with bachelor’s degrees.

Further, the higher education establishment’s emphasis on liberal arts bachelor’s degrees is out of sync with students’ legitimate concerns about debt and earnings and about the needs of local labor markets. Associate’s degrees, especially in technical fields, can be valuable. At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, students with technical/career- oriented degrees usually earn more, sometimes far more, than liberal arts graduates.

Finally, students with the same majors in the same state can achieve different incomes upon graduation depending on which college they attend. Students need to find out whether these comparative data exist across the schools they are considering. And if the data do not exist, they should ask their state legislators why not.

More generally, students, their parents, and their government representatives must insist that objective information about first-year earnings should be at every college-bound student’s fingertips. The White House’s proposed “college scorecard” might someday show earnings associated with different schools and programs, and the president has proposed sharing earnings and other data with students and their families. But even though taxpayers have paid hundreds of millions of federal dollars to build student-data systems that enable many states to report earnings data for each program in the state, most of this information gathers dust in data mausoleums, while the U.S. Department of Education has consistently failed to require states to use it.

Until the data about student earnings across the nation are unearthed and put to full use, many students will make poor decisions about schools and programs—decisions that will leave them saddled with debt and clamoring for some kind of government bailout. Students, lenders, taxpayers, and states should demand this information, and the federal government should make it easy to find and use. In the meantime, states that have taken the lead in releasing these data should be applauded and other states encouraged to follow their example.

While the wait continues for governments to make these data available, well over 6 million people have already fallen behind on their student loan repayments. Without the ability to make better-informed decisions, it can only be expected that more and more students will face drowning in a sea of red ink.