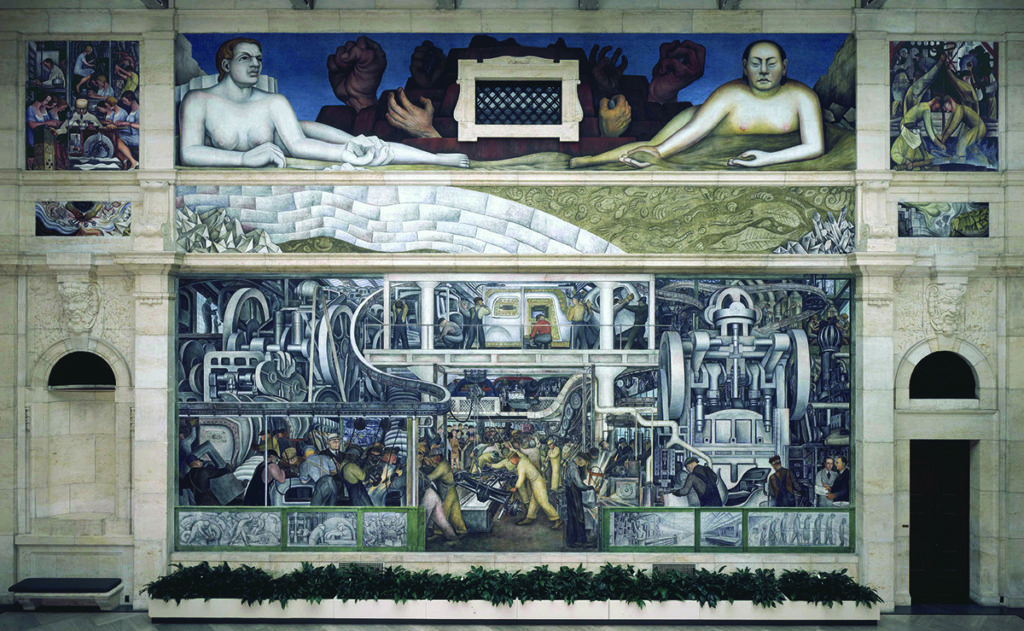

Detroit Industry Murals

The Detroit Industry murals by prominent Mexican artist Diego Rivera pay tribute to Detroit’s manufacturing base and labor force. In the first half of the twentieth century, Detroit was the center of America’s most important industry—automobile manufacturing—and it was a symbol of modernity and the power of labor and capitalism. Commissioned by Edsel Ford, then president of the Ford Motor Company, Rivera completed the 27-panel work at the Detroit Institute of Art in 1933. It is considered the finest example of Mexican mural art in the United States, and Rivera thought it his most successful work. A leader of the Mexican mural movement, Rivera sought to bring art to the masses through large-scale public works, which often featured stylized representations of the working classes and indigenous cultures of Mexico. Rivera saw industry as the indigenous culture of Detroit.

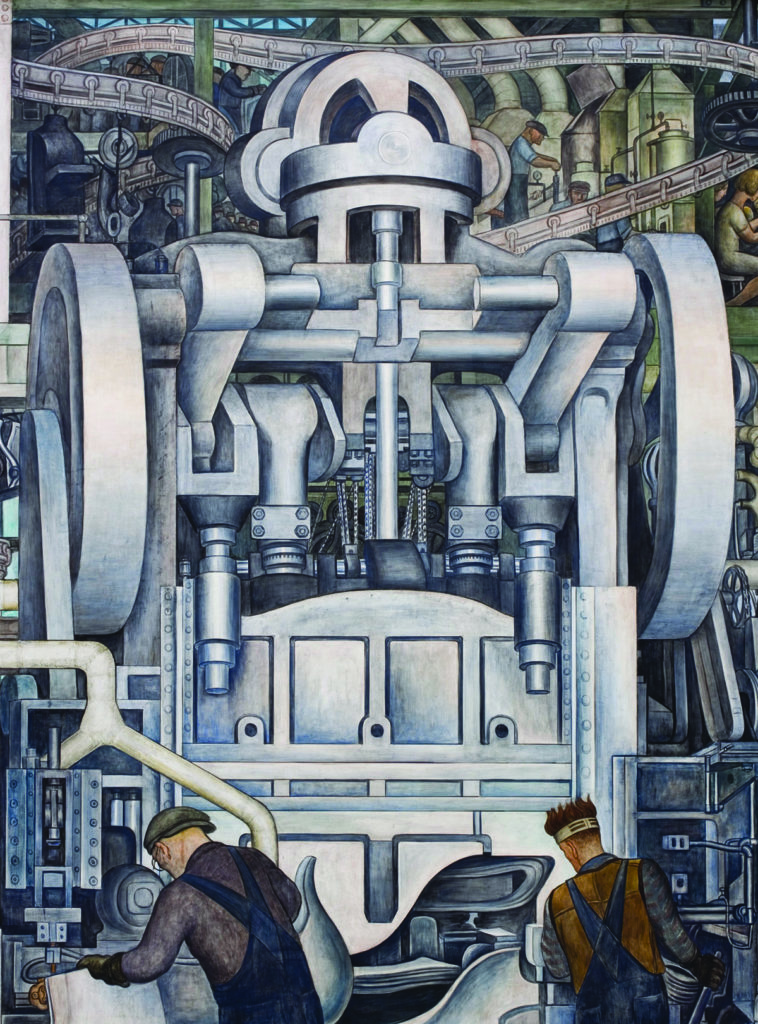

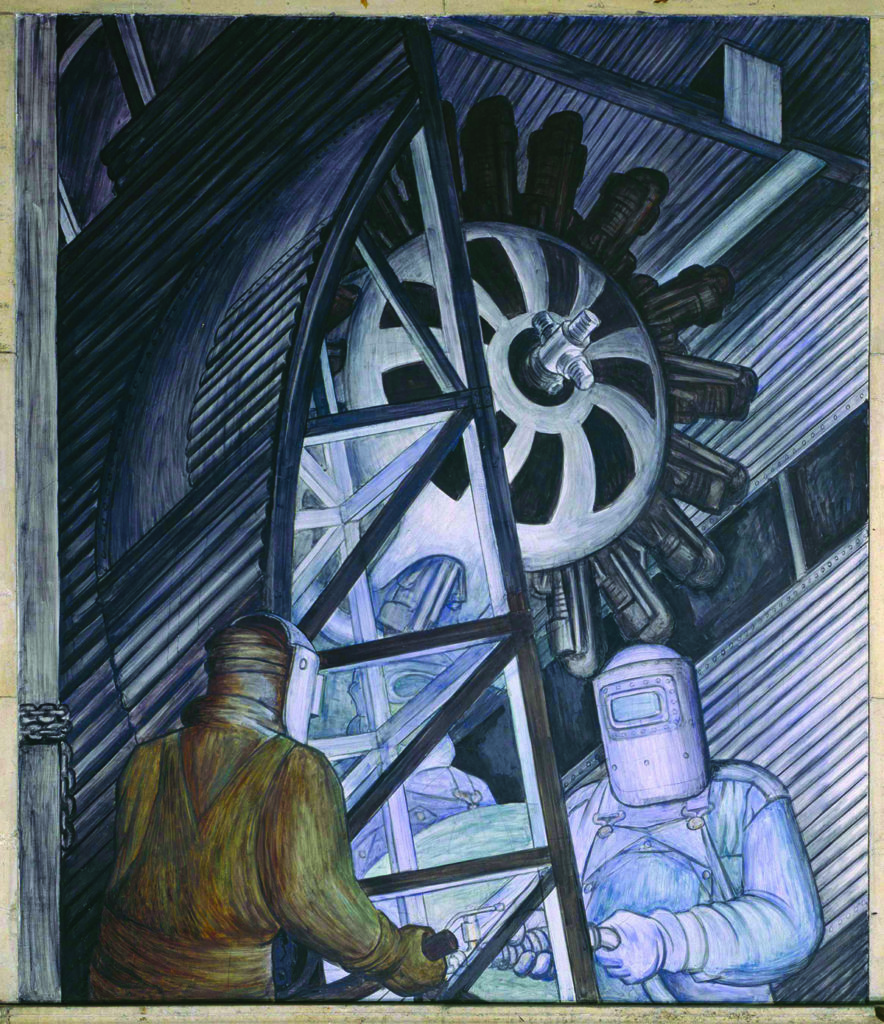

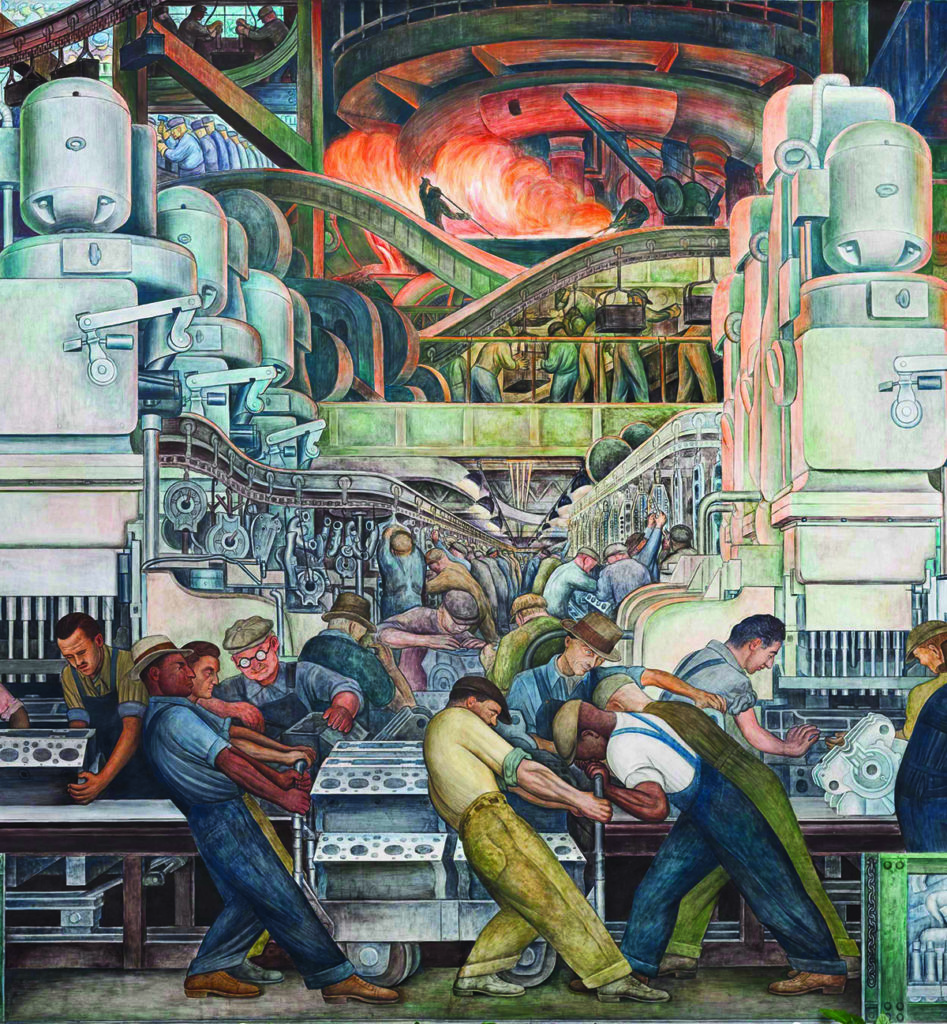

Depicting Detroit industry as a whole, with particular emphasis on the automobile industry, the murals highlight the duality—constructive/destructive, organic/mechanistic—of industry and technology. The courtyard featuring the murals is aligned on the east/west/north/south axis, and Rivera used this orientation symbolically. On the east wall, the direction of sunrise and beginnings, he depicts a baby in the bulb of a plant framed by plowshares and two women holding grain and fruit. Rivera’s imagery symbolizes fertility and bounty, and he references early agricultural technology. The north and south walls, which comprise the largest parts of the murals, depict the manufacture of the 1932 Ford V-8 at the company’s River Rouge plant. He drew upon his background in cubism, showing multiple angles simultaneously, to depict the bustling activity and relationship among processes taking place on the factory floor. On the west wall, the direction of sunsets and endings, Rivera continues the theme of the development of technology that he began on the east wall with depictions of aviation, shipping, and energy production. A passenger plane and military bombers clearly represent the benefits and dangers of technology, and depictions of a hawk and dove underscore this theme. Rich with symbolic meaning, the murals are at once an enthusiastic celebration of and a cautious warning against science, technology, and industry.

When the murals were unveiled, they sparked a major controversy. Some critics claimed that they were sacrilegious, others didn’t like images of the working class featured in such a prominent place, and still others were upset at the sum the artist was paid at the height of the Great Depression. The Detroit City Council even considered a vote to whitewash the murals. Today, the murals are considered one of the most important modernist works of the twentieth century and were given National Historic Landmark Status in 2014.

—Alana Quinn