Mischievous Maritime Art

In DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash, Brooklyn-based artist Duke Riley uses plastic collected from beaches and waterways of the northeastern United States to tell a story of local pollution and global marine devastation. Riley’s contemporary interpretations of historical maritime crafts—including scrimshaw, sailors’ valentines, and fishing lures—confront the catastrophic effect that single-use plastics have had on the environment. On view at the Brooklyn Museum in New York City, the works are presented alongside a selection of historical scrimshaw in the museum’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch settler period rooms, directly connecting environmental injustices past and present.

Riley replaces scrimshaw’s traditional medium—whalebone and walrus tusks—with discarded plastic containers and other found objects collected from waterways. The works incorporate the maritime imagery traditional to scrimshaw and expand it by replacing portraits of sea captains with depictions of international business executives that the artist identifies as responsible for the perpetuation of single-use plastics.

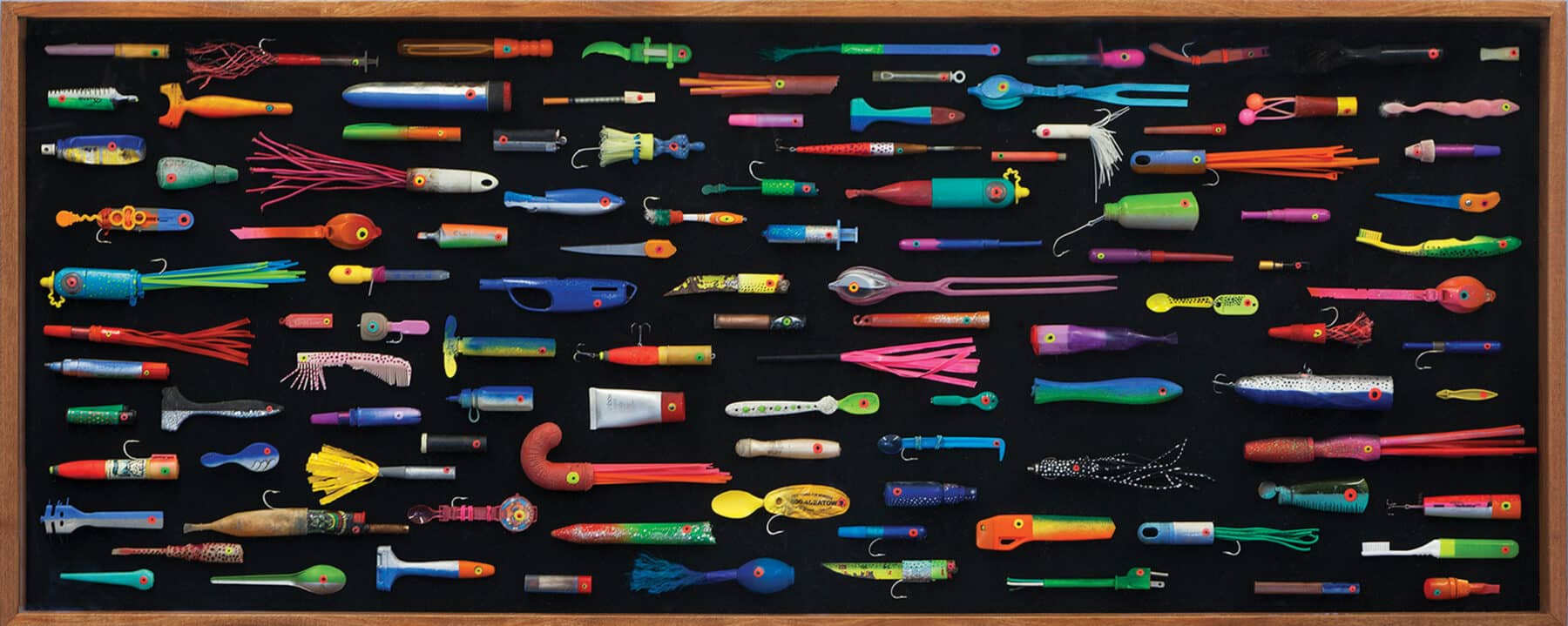

Also on view are Riley’s fishing lures and sailors’ valentines—originally a nineteenth-century nautical souvenir made of shells—created with cigarette butts, flossers, tampon applicators, bottle caps, and other detritus found on New York streets and waterfronts. The exhibition juxtaposes Riley’s art made from corporation-driven pollution with several of his new short films that highlight New York community members working to remediate plastic damage and restore waterways.

Born in Boston, Riley is fascinated by maritime history and life around urban waterways. Known for his mischievous streak, Riley works in a wide variety of media—mosaic, illustration, sculpture, film, and performance—to address tensions between individual and collective behavior and draw attention to sociopolitical and environmental issues.