COVID-19 Revealed an Invisible Hazard on American Buses

COVID-19 has forced the public transit industry to pay attention to air quality, which takes a particular toll on bus drivers.

Six months into this pandemic, at least 10,000 American transit workers have contracted COVID-19 and 89 members of the Amalgamated Transit Union, where I work on health and safety, have died of the disease. Although our union has been advocating for better ventilation inside transit vehicles for decades, it has taken COVID-19 to finally force the transit industry to pay attention to air quality—and the long-standing high rates of respiratory illness and infection among drivers.

Soon after the novel coronavirus surfaced in China, it became clear that it could be spread among passengers on public transit. In March, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that an infected passenger in the back of a bus transmitted the virus to nine people sitting within 15 feet. And in April came another report of a bus passenger infecting 22 people throughout the vehicle, who in turn caused an additional 20 secondary infections. These examples, together with knowledge from the basic fluid dynamics of aerosols and from research on the virus’s durability, have made it obvious that additional engineering and ventilation are needed to make buses in the United States safer for riders and operators.

Before I describe the best ways to make transit safer in both the short and long term, I need to explain why buses are currently so unsafe.

Air quality has never been a priority in the specifications and manufacture of public transit vehicles in United States. One reason for this is that poor air quality presents a risk that is invisible, and its principle result—excessive illness among drivers—is not something the industry tracks. This situation has been worsened by the impact of buy-American rules, which prevent spending federal transit dollars on buses not made here. This, coupled with the nation’s small number of bus manufacturers, results in a market that has been much slower to change than, say, the one for passenger cars. European buses, which are far superior from an engineering standpoint and significantly cheaper, are not currently available in the United States. As a result, US buses used for public transport are expensive and poorly designed—and now, faced by the challenge of COVID-19, the pared-down engineering resources of the industry have been struggling, unsuccessfully, to make necessary improvements.

Air quality has never been a priority in the specifications and manufacture of public transit vehicles in United States. One reason for this is that poor air quality presents a risk that is invisible, and its principle result—excessive illness among drivers—is not something the industry tracks.

In current US bus designs air flows along the length of the cabin, passing through low-grade filters, before being recirculated. Frequently, no fresh air is incorporated into the supply. One bus manufacturer, for example, only recirculates air—even though this could be remedied by the installation of a simple pipe to bring in fresh air from outside. This design is hazardous to passengers, who are regularly exposed to exhaust fumes that leak through the rear of the bus, as well as the viral and bacterial infections of other passengers.

For operators, however, the situation is considerably worse. Virtually all US buses are shaped like a brick, with squarish front corners, a design that means outside air striking the front of the bus is unable to make the sharp turn at the corners. Instead, the air shoots out to the side, leaving a low-pressure zone that pulls air from back to front inside the bus. This “leading-edge suction” pulls forward any airborne contaminants, including viruses and bacteria shed by the passengers, so they stream past the driver. Given the long shifts common in an industry unable to attract and retain enough drivers, exposure to these aerosols is a persistent hazard.

In fact, more than 60 years of occupational health research have shown the harms of operating buses. In addition to having exceptionally high rates of hypertension, depression, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal injuries, and diabetes, bus drivers also suffer from problems related to the poor ventilation. For example, rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—familiarly known as COPD—are 70% higher than in the general population.

So when COVID-19 hit, the bus drivers’ preexisting conditions and the well-known problems of ventilation on the buses combined to create a disaster. Wearing a mask can help, but due to the early lack of N95 respirator supplies, drivers weren’t assured of having one readily available to make extended exposure to the virus on buses safer.

Going forward, much more significant efforts are needed to engineer better ventilation in buses for both drivers and passengers. First, the industry can apply short-term fixes, but it must eventually institute higher standards to protect the long-term health of passengers and operators.

The easiest thing to fix is the low-quality air filters currently used. Designed to remove large particles, they are primarily intended to protect bus hardware, rather than passengers. Upgrading filters has been challenging, however, because bus ventilation systems were not designed to allow installation of high-performance filters, which simply don’t fit.

Virtually all US buses are shaped like a brick, with squarish front corners, a design that means outside air striking the front of the bus is unable to make the sharp turn at the corners. This “leading-edge suction” pulls forward any airborne contaminants so they stream past the driver.

Complicating the task is the fact that neither the industry nor the federal government has established standards for filtration—so every local agency is on its own, trying to reengineer safe buses. (It is as if you were trying to engineer the safety elements of your own car; transit agencies simply do not have the expertise for the task.) Partnering with several transit agencies, our union has successfully tested filters rated MERV-13, which can remove roughly half the fine particles with each pass of air through the heating, ventilating, and air conditioning system. In current HVAC systems, this is the best we can hope for, and upgrades should be done immediately. However, we are pushing for the more extensive modifications required to install higher-quality filters—at least as good as the HEPA filters found in common vacuum cleaners.

Although filtration systems can remove particles, it is our union’s opinion that ultraviolet sterilization of the air flow should be standard on public transit. Robust ultraviolet control (UVC) systems should be required so that all biohazards are neutralized in a single pass through the unit. Not only is this change long overdue; the advanced systems would on the whole be less expensive than the ones currently in operation. In fact, a 2009 National Academies study found that installing electrostatic filters and UVC not only inactivated a wide range of biohazards but also paid for itself in only 18 months through reduced maintenance costs. Despite the potential to save money, never mind making bus environments healthier, these improvements are not standard.

A 2009 National Academies study found that installing electrostatic filters and UVC not only inactivated a wide range of biohazards but also paid for itself in only 18 months through reduced maintenance costs. Despite the potential to save money, never mind making bus environments healthier, these improvements are not standard.

Although these immediate improvements can greatly improve safety, there is a need for a more radical redesign to ensure air quality and safety in buses (and, it should be added, rail cars as well). When the pandemic began, I contacted Andrew Krum and his team at the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute and Robert Breidenthal at the University of Washington Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. They proceeded to model interior airflows in buses and engineer changes that could protect passengers and drivers. The Federal Transit Administration (FTA) has supported those efforts and provided valuable engineering insights. The efforts have resulted in development of a prototype barrier that protects the transit operators in a bubble of fresh air, which then flows into the passenger area to improve overall ventilation.

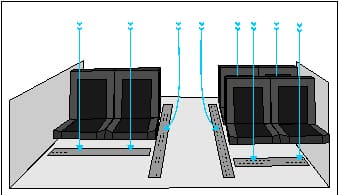

Far more revolutionary changes are possible. We could provide passengers and drivers with the sort of vertical airflow pattern seen in laboratory clean rooms. With a grid of holes along a bus’s ceiling supplying fresh, filtered, and UV-sterilized air, and return-air grills in the floor, a vertical flow could keep each passenger in a fairly isolated column of clean air. This concept originated with Professor Breidenthal, who used a mathematical model to show that it is feasible. Although there would be some mixing of air, it would be vastly harder for one person in the back of the bus to infect other passengers nearby, much less throughout the entire bus. This same approach can and should be used in rail vehicles and even elevators.

This proposal is one of two initiatives we’re pursuing in the hope of redesigning public transit in the United States from the ground up. It is now being considered by the National Academies Transportation Cooperative Research Project. The second initiative, with the FTA, seeks to correct a range of safety hazards to drivers, passengers, and pedestrians. We also are proposing improvements to customer service with the goal of reaching and exceeding best global practices.

COVID-19’s arrival highlighted, with stunning clarity, that transit safety has long been neglected. This injustice dates to the age of horse-drawn trolleys, when horses were regularly swapped out to keep them from getting too cold during harsh winters, but no such protection was offered for operators, who worked long hours in the cold. Replacing a horse was expensive, while replacing a driver simply meant hiring another. Congress had to pass the Vestibule Act of 1905 to force trolley operators in Washington, DC, to provide even modest (but still unheated) shelters for drivers.

Earlier this year, when the pandemic was just taking hold, some people were surprised when transit agencies such as the New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority demanded that operators remove their protective masks to avoid frightening the public. But this has been the pattern for over a century; whenever the hazards on public transit have been invisible, decision-makers have seen safety as inconvenient, and transit workers and members of the public have suffered or died.