Reworking the Federal Role in Small Business Research

The U.S. economy is changing rapidly, and the Small Business Investment Research program must change with it.

After 16 years of experience and almost $10 billion in federal expenditures, the SBIR program is showing its age. It has lived through business’s technology-driven metamorphosis more as an observer than as a player and does business today much as it did in 1982. Although most of our knowledge of the program’s successes and failures is anecdotal, it is clear that the program’s growth over time has been largely at the expense of other federal R&D support for small business. Also, most SBIR awards aimed at the commercial marketplace do not lead to major commercial successes and most SBIR awards aimed at government needs do not result in federal procurement contracts. If small businesses are being asked to assume a more important role in innovation, the government’s flagship program of assistance to these businesses must be relevant. We recommend a series of changes in the SBIR statute and program which we feel will attract additional companies, help those companies become more responsive to their federal and private sector customers, enable program administrators to do their jobs better, and permit the program to continue to improve as the inevitable evolution of business continues into the 21st century.

In the beginning

SBIR began at the National Science Foundation (NSF) in 1977, according to the program’s father, Rolland Tibbetts. SBIR was conceived as a merit-reviewed program of high risk/high payoff research that the government would fund from conception through the prototype stage. By targeting small high technology firms that for their size contribute disproportionately to technological innovation, economic growth, and job creation, NSF hoped to increase federal research’s economic return on investment to the nation.

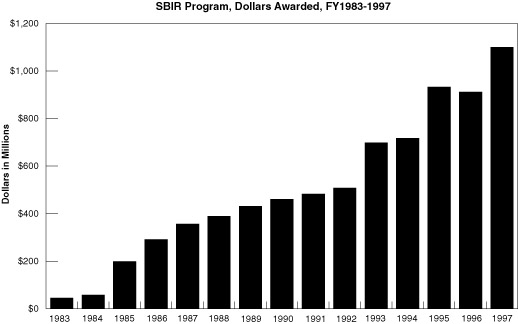

The SBIR program was formally launched as a ten-agency, applied research experiment by the Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982. The bill’s primary sponsors believed that by shifting some money from the large corporations and universities that received most federal research funding to small innovative companies, the government would get better research at a lower price and small businesses would develop new products and services to sell in the commercial market. Before SBIR, businesses with fewer than 500 employees were winning only 3.5 percent of government research grants and contracts. Federal procurement officials functioned within a conservative system and were unwilling or unable to risk increasing awards to untested small businesses. The new law required each federal agency with a $100 million research budget to set aside 0.2 percent of its Fiscal Year 1983 extramural R&D funding ($45,000,000 per year) for small businesses. This would provide a floor for small business, introduce federal agencies to a new universe of potential contractors and grantees, and provide small businesses with much-needed funds to conduct research and develop new products. The size of the set-aside was increased to 1.25 percent during the first six years of the program and was increased to 2.5 percent (over $1 billion per year) during the five years ending in FY 1997.

Although any government program needs to be reexamined periodically, the rationale for reviewing SBIR is particularly compelling because the business environment has changed so much since 1982. The SBIR program began in the typewriter age, one month after the unveiling of the original IBM personal computer. Business communications were conducted by telephone and by mail; fax machines existed, but it was pure luck when the receiving and sending machines were compatible. DARPANET had not yet become NSFNET, let alone the Internet, and data exchange protocols were far in the future. The Dow Industrial Average was at 925.13, unemployment was at its highest level since 1941, and the savings and loan bailout was just beginning.

The era of cooperation in research had not yet begun; in fact, business was conducting research much as it had a decade or two earlier. In 1982, major companies tended to depend on their own centralized corporate research laboratories; today, collaboration and the use of contractors or suppliers for research is common. The changes in the antitrust laws that opened the way to widespread corporate partnering had not yet occurred, nor had the tendency within corporations to require their corporate research organizations to place a primary focus on the short-term problems of their operating divisions.

The federal government’s share of the research pie was larger than today, and well over half of government research was defense-oriented. Since the Bayh-Dole patent policy and Stevenson-Wydler technology transfer policy were new, there was little commercialization of federal research results. Companies were just beginning to increase their investments in research universities, and there were few university research parks or incubators. Venture capital levels were about one percent of current levels. Most of the state and federal programs that now help small businesses did not exist, and the Reagan administration took a dim view of any government involvement in the commercial marketplace.

We viewed the world more simply in 1982. SBIR followed a simplistic linear commercialization model that assumed that the research and commercialization phases are completely separate, and the program ignored differences in applicants’ size and level of sophistication. Each had to begin with a Phase I award, a small government grant capped at $50,000, to determine scientific and technical merit of a specific concept. If successful in Phase I, companies could then apply for more substantial Phase II funding of up to $500,000 to develop the idea to meet particular program needs. Responsibility for Phase III, commercialization, was left to the private sector except for an occasional federal procurement contract when the government was the customer.

The 1982 legislation embraced a diverse set of goals that included stimulating technological innovation, using small businesses to meet federal R&D needs, fostering and encouraging participation by minorities and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation, and increasing the private sector’s commercialization of innovations derived from federal R&D. Unfortunately, the Act’s reporting requirements ignore innovation. All they require is that agencies spend the entire set-aside and shield small businesses from burdensome reporting requirements.

Program evolution

The program quickly became politically popular, and in 1986, two years ahead of schedule, was approved for an additional five years. The renewal legislation required the General Accounting Office (GAO) to study the effectiveness of all three phases of the program in preparation for the next congressional program review in 1992.

By 1992, the program had strong support in the small business community and was no longer as threatening to small business’s competitors for federal research dollars. Yet, the divergence between the SBIR program and the original target group of companies had already begun. By 1992, small business had become an important engine for innovation and economic growth. A new breed of small technologically sophisticated companies were springing from universities and other technology centers to the forefront of emerging industries such as software, biotechnology, and advanced materials, and venture capitalists were responding. Scientists and engineers who had previously stayed in academia moved to industry part-time or full-time. These companies had needs, but they were hard to meet in the rigid structure of the SBIR program.

Despite the growth of the set-aside to 1.5 percent, small business’s share of total federal R&D grew by only 0.3 percent. Why didn’t the set-aside produce markedly greater participation? One possible explanation is that agencies shifted those small businesses with a history of winning contracts through open competitions into their SBIR program. With the contract research came larger, established small businesses whose focus was on winning government contracts rather than developing innovative products for the commercial marketplace. They lobbied hard to protect what they had, to expand the program without substantive change. GAO recently reported to the Committee on Science on the magnitude of this situation. The top 25 SBIR Phase II award winners in the first 15 years of the program won 4,629 phase I and II awards worth over $900 million. SBIR accounts for 43 percent of the total operating revenues of these companies, all of which have been in the program for at least ten years.

For the most part, the contract researchers got what they wanted. Congress doubled the size of the set-aside to 2.5 percent and set no limits on the number of SBIR awards a single company could win (although the program’s goals were rewritten to emphasize commercialization). SBIR agencies were encouraged to bridge the funding gap between SBIR Phase I and Phase II and to set up discretionary programs of technical assistance for SBIR award winners. Agencies were asked to keep track of the commercialization successes of multiple award winners and to give more serious consideration to the likelihood of commercial success when evaluating applicants. The caps on award sizes for SBIR Phase I and Phase II were raised to $100,000 and $750,000 respectively.

Less was done to address the changing nature of small business. A very small companion pilot program known as the Small Business Technology Transfer Program (STTR) was established to transfer technology from federal labs and universities to small business, but STTR paralleled SBIR’s linear development model. Agencies were still given complete discretion on research topics for SBIR grants but encouraged to give grants in critical technology areas.

In 1997, Congress took an important step toward making SBIR and STTR more accountable when it brought both programs under the aegis of the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), which requires program managers to state outcome-related goals and objectives and to design quantitative performance measures. We believe that this move has the potential of eventually reversing the SBIR tradition of minimal program evaluation.

The 1992 and 1997 changes and related agency actions were essentially a fine-tuning of the program rather than a redirection. It is still true that a few SBIR grantees achieve half of the program’s commercial success and that the average SBIR grant still does not lead to significant commercial activity.

Today’s challenges

The accelerating rate of change in the business environment for small technology-oriented and manufacturing firms adds to the need for further reforms. The business revolution of the past ten years is likely to continue for some time. Product cycles have shrunk to a fraction of what they were a decade ago. Many large corporations no longer have deep in-house scientific and technical capabilities and have pushed more design, innovation, and manufacturing responsibilities onto their subcontractors. Products are frequently designed jointly with suppliers locally or globally. International quality standards must be met throughout the supply chain. Small businesses that cannot produce with world-class quality on a real-time basis will increasingly run the risk of losing business to those at home or abroad that can.

The linear model of innovation has become obsolete. When product cycles are measured in months, we no longer have a year to perfect an idea, another year to build a prototype, and yet more time to commercialize the idea. The Internet, the internationalization of standards, and the dropping of barriers to international trade will only accelerate the process of change. Companies that historically have worried about a few local competitors must now be able to satisfy a customer who can compare the prices and delivery schedules of companies across the globe.

The pressures on small businesses to produce either low-cost quality goods or a truly unique product can only increase.

And this is just the beginning of the revolution. No one can really anticipate the changes in customer/supplier relations for research as well as for commercial products if another thousand-fold increase in computing power and bandwidth occur over the next 15 years, but we have to try. It is time to think outside the envelope. As SBIR programs are subjected to GPRA, we hope that research managers will examine not what has worked in the past but how business will be conducted in a few years. They need to look for answers to the following questions: What will be required for U.S. small businesses to become the suppliers of choice for major companies around the world? How can the percentage of SBIR winners with major market successes be increased significantly? Why after $10 billion of SBIR effort are small businesses not better accepted as government contractors? How can SBIR efforts complement those of the other federal, state, and local programs that provide services to smaller manufacturers and high technology companies?

The Congress also, as it considers legislation to reauthorize the SBIR program, needs to take bold steps to modernize the program and to correct its weaknesses. In this spirit, we recommend a number of changes to the program that we believe would clarify program priorities, involve the broader business community in the program, give SBIR grantees the tools they need to succeed, and provide program administrators adequate resources and flexibility.

Clarifying program priorities. It is time to clarify that the purpose of the SBIR program is innovation and that that innovation is to be measured by the extent to which innovative ideas find their way into commercial products and federal procurements. Measures of success will be different in the two areas. The current practice of including both federal use and commercial sales in the same commercialization totals makes it more difficult to understand how an SBIR program is really doing. The unified report should be replaced by separate reports that show the breadth and depth of the use of the SBIR product or research by the government and by the commercial marketplace. Further, each agency, under the GPRA process, should set and monitor targets for each of the two major goals of the program. For the National Science Foundation, the sole goal for SBIR should probably be commercial products; for a mission agency such as the Department of Defense, a certain fraction of the SBIR pie devoted to federal procurement is more appropriate.

Under current law, agencies have complete discretion in choosing SBIR research topics. These topics need to be high priority and reflect commercialization potential. If more SBIR solicitations coincided with the major initiatives of an agency or an administration, small businesses would develop the expertise for follow-on work that is not funded through the SBIR program. As described more fully later, if SBIR solicitations seek topics with major commercial potential, grantees will have a better chance of establishing expertise in a hot commercial field. This change should be possible to do administratively except a statutory change may be necessary to give priority within SBIR to high-profile multiagency initiatives. After program goals are clarified, it is also important to develop specific measures of success for the SBIR program that can be verified by the GAO and studied by outside researchers.

Creating an orientation within SBIR toward the ultimate private sector and government customers. We owe the taxpayers as high an SBIR commercialization success rate as possible, and success requires preparation. The SBIR application evaluation process should value commercialization as much as a prototype, and a business plan should be required of Phase I applicants. Applicants should be graded on commercial as well as technical merit. Commercial merit could include the applicant’s level of understanding of where the proposed innovation fits in the commercial or government marketplaces, the quality of its business plan, its plans for acquiring the skills and expertise necessary for commercialization, and its support network, including government or private sector promises of business or technical support. A prior positive record in commercializing new technology should be viewed positively in applications for either phase, regardless of whether that commercialization occurred within the SBIR program.

Small technology businesses are not commercial islands. Their products generally end up either as a component in someone else’s product or as a finished product sold to major customers. The chances of SBIR commercialization increase dramatically when these customers are involved in the development process, because the market’s judgment of the importance of an innovation is being substituted for that of a government employee. The willingness of a potential customer of an SBIR product to be a partner during Phase II may well be the ultimate marketplace indicator of product acceptance. Letters of intent from potential customers in either the private or public sectors to purchase the successfully developed product should also be considered positively. For those SBIR awards that are geared toward federal agency customers, expressions of interest such as matching funds from outside the SBIR program or commitments to procure if the prototype meets agency needs should carry extra weight in the evaluation process.

The know-how of venture capitalists, typical customers, and suppliers of other support services to small business are essential to the success of SBIR but not generally available within the agencies with SBIR programs. Carefully constructed advisory panels in each agency could better attune the SBIR program personnel to market needs.

SBIR funds are a limited resource that each year go to only one or two percent of small manufacturers and high-technology companies. The resource is too precious to be spent on topics that interest neither the private sector nor federal procurement officials. SBIR awards should be aimed at specific products or services needed by the government or likely to succeed in the commercial marketplace. A wide net should be cast for ideas both in the private sector and in the mission portions of agencies before focus areas for SBIR grants are established. Mechanisms for consideration of unsolicited proposals with strong industrial support should be considered.

Only a fraction of the companies that could benefit from SBIR win awards each year. These limited resources should go to innovative companies that are looking for profits from sales in the commercial marketplace or from sales to a sponsoring agency and its contractors rather than those looking for profits from conducting the SBIR research. Although government contract research with small business will be desirable in a variety of instances, it is not the best use of these funds; we must look for ways to pay for it outside of the SBIR program, perhaps by recasting solicitations for contract research in a way that gives added weight to the lower cost structure of small business. Returning small business contract research to the regular procurement system should sharpen the SBIR program’s focus on commercialization and correspondingly decrease the number of frequent winners. If it does not, it may be necessary to look to limits on the number of awards that one company can receive or to give preference within the SBIR program to smaller companies.

Strengthening small businesses. It is not unusual for a company to be competent technologically, but to fail because other skills are lacking. There are now numerous programs such as the Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP), the federal laboratories, the Small Business Development Centers (SBDC), and state and local assistance programs designed to help small business, but each works only on a limited range of problems. The SBIR program should have close working relations with these other programs. If an SBIR winner needs to acquire the capabilities to manufacture without defects to all applicable standards at a competitive price, it may be prudent to link that company with MEP in the early stages of the SBIR process. If a company is weak in business and marketing skills or needs help with finding capital or a partner, the SBIR program should act as a referral agent to the SBDC and other programs as needed.

The shortage of travel funds in most SBIR programs has left too many SBIR winners to fend for themselves and has limited the ability of SBIR program officers to monitor the research they are funding. Other business-oriented programs such as the MEP, the Agricultural Extension Service, the Small Business Development Centers, and the technology transfer arms of the national laboratories have skilled professionals at hundreds of locations around the country. The program would be strengthened if the various SBIR centers developed cooperative arrangements where specific, locally based agents from these other programs were available to assist SBIR winners as needed. They could also evaluate the progress of SBIR awardees periodically, recommend termination in hopeless cases, and help other winners shore up weaknesses and get the help they need.

Agency-oriented reforms. We recommend a very fundamental SBIR reform. Why not allow any program within an SBIR-participating agency that can demonstrate that it allocates at least 7.5 percent of its funds to small businesses to withdraw its share of R&D funds from the agency’s SBIR commitment? This would create incentives among program officers to work with the best small firms so that those officers could recapture control of the funds now passed through to SBIR. It would also create incentives for strong SBIR performers to do more program-driven R&D for agencies. This incentive would be much more effective than an SBIR set-aside in strengthening the capacity of small business to meet federal needs. SBIR itself might shrink, but small businesses would capture a larger share of the R&D pie.

Many other agency reforms would be desirable. Phase I grants are small enough that many high technology companies do not think they are worth applying for. We have been told that some companies’ application costs exceed the amount of their Phase I awards. However, for small startup companies, Phase I may be the best way to get started. Therefore, flexibility concerning Phase I is in order. To broaden the applicant pool and to increase the quality of applicants, Phase II awards should be opened up to companies that have not received Phase I awards but that can show that they have made a similar level of progress on their own or through funding from other programs.

Reconsidering spending and time limits also is in order. The SBIR program, which is essentially preparing a portfolio of investments for the venture capital, corporate, or further government investment, is placing too many small bets to be efficient. In contrast to SBIR’s $100,000 and $750,000 limits, Commerce’s Advanced Technology Program is able to make awards to individual companies of up to $2 million and to extend these grants over a longer period of time. The SBIR program should have the flexibility to fund ideas that can get to the market quickly and to fund some longer-term, more complex projects as well. If there is a way to build in reviews so that the government can cut losses for projects that are not working out, it would be more efficient to allow the program to give a smaller number of larger awards rather than to give multiple Phase I and Phase II awards to the same small business in the same year.

It is also important to revisit the overhead question. SBIR programs have been hamstrung by the inability to use any of the SBIR set-aside for administrative expenses. A strong SBIR program needs strong administration, including rigorous evaluation of applications, oversight of grantees, and careful evaluation of program results. We like the idea of a fixed percent of the set-aside being used for administrative expenses. The exact amount can be determined with experience.

Within program goals, SBIR programs should be free to target the size and type of company where funding can be most useful. After 16 years, it should be possible to make some predictions about the profiles of companies that can gain the most from SBIR funding and to target such companies in a solicitation.

It is clear that the changing marketplace is going to force small businesses to become more nimble. The SBIR program will need to change as well. SBIR managers should have the flexibility to use part of their funding for experiments to learn how to do a better job of allowing SBIR awardees to meet the priority needs of their private sector and government customers. Experiments could address the following types of questions: Would it make sense to use some SBIR funds to seed the small business component of partnerships between small businesses and their private sector customers and to give instantaneous approval if the partner is willing to put enough at risk? Are there ways to use SBIR funding to introduce small businesses to federal procurement officials and to eliminate the risk to procurement officials when making awards to small businesses with no federal procurement track record, perhaps through a combined Phase II and III for sophisticated small high technology companies? Could partnerships with state and local research organizations be structured to increase the number of quality applicants from areas of the country that are underrepresented in SBIR awards? Given the number of faculty who are now able to balance corporate and academic responsibilities, is it still necessary in all instances to require the principal investigator on an SBIR grant to spend most of his time on that project?

In agencies that do not have a small business advocate, SBIR program officials should be given the responsibility to look out for the interests of small business throughout their agencies. They could then perform tasks such as advocating for more procurements for small businesses, including winners of SBIR awards, and referring appropriate small business candidates for non-SBIR research opportunities. They could recommend changes in agency policy or law that would give small business a more level playing field and serve as ombudsmen for small businesses that were trying to overcome barriers.

Preparing for future improvements. We seem to know less about the results of the SBIR program than about any comparable program. Perhaps this is because the program is set up as a tax on other programs and funding does not have to be justified annually. Perhaps this is because administrative expenses (and presumably evaluation expenses) by law cannot come out of the set-aside and some agencies are more willing than others to seek extra evaluation expenses. Sixteen years after program creation, the General Accounting Office had to work with the Small Business Administration on assigning discrete identifiers for each SBIR company and on developing common understandings of program goals so that they could be measured. In contrast, the Advanced Technology Program set out performance measures in advance of its first grant and has studied each completed project to determine the extent to which those measures have been met. Although SBIR will unveil a new data base later this year, this will help only if there is agreement on data needed to determine program strengths and weaknesses, if those data have been collected from SBIR awardees in usable form, and if analysis of the program is given a higher priority and stable funding. The best way to acquire these skills is to benchmark other programs.

SBIR programs should be able to learn from the private sector how to set up the data collection and analysis it needs in a way that is unobtrusive and protects the privacy of its clientele. Recent increases in computer power and the availability of increasingly sophisticated analytical tools should be used to the program’s advantage to help it maximize the gains to the taxpayers from their investment in SBIR.

Nurturing independent academic experts to study SBIR and answer basic questions about it, as has been begun by the National Research Council, should pay dividends. Here are examples of the questions we would like to see discussed. What is the highest and best use of SBIR funds? Should all small companies from the five-person startup to the well-established 500-person firm, have to meet the same standards for assistance? Should a company that has qualified for $20 million or more in SBIR awards still be considered a small business for purposes of this program, or should other companies be given a chance at the money? What is the best way to graduate companies from the program? Are there ways that SBIR can be used to leverage other opportunities for small businesses with agencies and their prime contractors? What are the best means of ensuring that the program receives high quality applicants from underrepresented geographical areas? Conducting studies on these and other topics clearly could increase the effectiveness of the program.

The SBIR Program has come a long way but cannot rest on its laurels. Because SBIR is an entitlement program with few strings attached and because there is no real outside constituency for its reform, we expect strong resistance to changes in the SBIR statute. Almost 30 years ago, Theodore Lowi pointed out the problem of trying to tackle programs that have concentrated benefits and widely distributed costs. Those who benefit from a program, seeing their interests so clearly, are very active in its defense, whereas those who bear the widely distributed costs have little incentive to use their energy and capital to push for change. SBIR has become a classic example of this political logic. A small number of companies have an enormous incentive to be very active in defense of the status quo. It is an open question whether we can overcome this political hurdle to try to make the SBIR program work smarter and produce better results for the Nation, but we hope this article will at least help frame some terms for discussion as we more toward authorization.